Zhou Enlai

|

周恩来

Zhou Enlai |

|

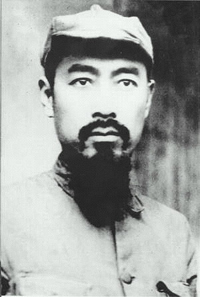

Zhou Enlai in 1940 |

|

|

1st Premier of the PRC

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 1 October 1949 – 8 January 1976 |

|

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng |

|

1st Foreign Minister of the PRC

|

|

| In office 1949 – 1958 |

|

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Chen Yi |

|

2nd Chairman of the CPPCC

|

|

| In office December 1954 – January 8, 1976 |

|

| Preceded by | Mao Zedong |

| Succeeded by | vacant (1976-1978) Deng Xiaoping |

|

|

|

| Born | March 5, 1898 Huaian, Jiangsu, Chinese Empire |

| Died | January 8, 1976 (aged 77) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Political party | Communist Party of China |

| Spouse | Deng Yingchao |

| Religion | Atheist |

Zhou Enlai (simplified Chinese: 周恩来; traditional Chinese: 周恩來; pinyin: Zhōu Ēnlái; Wade-Giles: Chou En-lai) (5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, serving from October 1949 until his death in January 1976. Zhou was instrumental in the Communist Party's rise to power, and subsequently in the construction of the Chinese economy and restructuring of Chinese society.

A skilled and able diplomat, Zhou served as the Chinese foreign minister from 1949 to 1958. Advocating peaceful coexistence with the West, he participated in the 1954 Geneva Conference and helped orchestrate Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to China. Due to his expertise, Zhou was largely able to survive the purges of high-level Chinese Communist Party officials during the Cultural Revolution. His attempts at mitigating the Red Guard's damage and his efforts to protect others from their wrath made him immensely popular in the Revolution's later stages.

As Mao Zedong's health began to decline in 1971 and 1972, Zhou and the Gang of Four struggled internally over leadership of China. Zhou's health was also failing however, and he died eight months before Mao on 8 January 1976. The massive public outpouring of grief in Beijing turned to anger towards the Gang of Four, leading to the Tiananmen Incident. Deng Xiaoping, Zhou's ally and successor as Premier, was able to outmaneuver the Gang of Four politically and eventually take Mao's place as Paramount Leader.

Contents |

Early life

Zhou Enlai was born to a well-educated couple in 1898 or 1899[1] in Zhejiang, and spent most of his early years in Huai'an, Jiangsu. His education included the Chinese Classics and, later, the prestigious Tianjin Middle School. From there, he studied at Waseda and Nippon universities in Japan, and later attended Nankai University in Tianjin.

Revolutionary activities

Zhou first came to national prominence as an activist during the May Fourth Movement. He had enrolled as a student in the literature department of Nankai University, which enabled him to visit the campus, but he never attended classes. He became one of the organizers of the Tianjin Students Union, whose avowed aim was “to struggle against the warlords and against imperialism, and to save China from extinction." Zhou became the editor of the student union’s newspaper, Tianjin Student. In September, he founded the Awareness Society with twelve men and eight women. Fifteen year old Deng Yingchao, Enlai’s future wife, was one of the founding female members. (They were married on 8 August 1925). Zhou was instrumental in the merger between the all male Tianjin Students Union and the all female Women’s Patriotic Association.

In January 1920, the police raided the printing press and arrested several members of the Awareness Society. Enlai led a group of students to protest the arrests, and was himself arrested along with 28 others. After the trial in July, they were found guilty of a minor offense and released. An attempt was made by the Comintern to induct Zhou into the Communist Party of China, but although he was studying Marxism he remained uncommitted. Instead of being selected to go to Moscow for training, he was chosen to go to France as a student organizer. Deng Yingchao was left in charge of the Awareness Society in his absence.

French "studies" and the European years

On 7 November 1920, Zhou Enlai and 196 other Chinese students sailed from Shanghai for Marseilles, France. At Marseilles they were met by a member of the Sino-French Education Committee and boarded a train to Paris. Almost as soon as he arrived Zhou became embroiled in a wrangle between the students and the education authorities running the “work and study” program. The students were supposed to work in factories part time and attend class part time. Because of corruption and graft in the Education Committee, however, the students were not paid. As a result they simply provided cheap labour for the French factory owners and received very little education in return. Zhou wrote to newspapers back in China denouncing the committee and the corrupt government officials.

Zhou traveled to Britain in January; he applied for and was accepted as a student at Edinburgh University. But the university term didn’t start until October so he returned to France, moving in with Liu Tsingyang and Zhang Shenfu, who were setting up a Communist cell. Zhou joined the group and was entrusted with political and organizational work. There is some controversy over the date Zhou joined the Communist Party of China. For secrecy reasons members did not carry membership cards. Zhou himself wrote "autumn, 1922" at a verification carried out at the Party's Seventh Congress in 1945.

There were 2,000 Chinese students in France, some 200 each in Belgium and England and between 300 and 400 in Germany. For the next four years Zhou was the chief recruiter, organizer and coordinator of activities of the Socialist Youth League. He traveled constantly between Belgium, Germany and France, safely conveying party members through Berlin to entrain for Moscow, to be taught the art of revolution.

The First United Front

Zhou returned to China as a seasoned party organizer in 1924. He was appointed Director of the CCP Guangdong Military Affairs Department, Director of Training at the National Revolutionary Army Political Training Department and Acting Director of the Whampoa Military Academy's Political Department. The latter role made Zhou political commissar of the 1st Division, 1st Corp during the Eastern Campaign of 1925.[2] At the end of that successful campaign, he was named CCP Secretary of Guangdong Province, one of the highest jobs in the party. A year later, at the age of 28 or 29, Zhou Enlai was elected to the CCP Politburo and placed in charge of military affairs.

In January 1924 Sun Yat-sen had officially proclaimed an alliance between the Kuomintang and the Communists, and a plan for a military expedition to unify China and destroy the warlords. The Whampoa Military Academy was set up in March to train officers for the armies that would march against the warlords. Russian ships unloaded crates of weapons at the Guangzhou docks. Comintern advisers from Moscow joined Sun’s entourage. In October, shortly after he arrived back from Europe, Zhou Enlai was appointed Director of the political department at the Whampoa Military Academy in Guangzhou.[3]

Zhou soon realized the Kuomintang was riddled with intrigue. The powerful right wing of the Kuomintang was bitterly opposed to the Communist alliance. Zhou was convinced that the CCP, in order to survive must have an army of its own. "The Kuomintang is a coalition of treacherous warlords" he told his friend Nie Rongzhen, recently arrived from Moscow and named a vice director of the academy. Together they set about to organize a nucleus of officer cadets who were CCP members and who would follow the principles of Karl Marx. For a while they met no hindrance, not even from Chiang Kai-Shek, the director of the academy.

Sun Yat-sen died on 12 March 1925. No sooner was Sun dead than trouble broke out in Guangzhou. A warlord named Chen Chiungming made a bid to take the city and province. The East Expedition, led by Zhou, was organized as a military offensive against Chen. Using the disciplined core of CCP cadets they met with resounding success. Zhou was promoted to head Whampoa’s martial law bureau. Zhou quickly crushed an attempted coup by another warlord within the city. Chen Chiungming once again took the field in October 1925. Once again Zhou defeated him and this time captured the important city of Shantou on the South China coast. Zhou was appointed special commissioner of Shantou and surrounding region. Zhou began to build up a party branch in Shantou whose membership he would keep secret.

On 8 August 1925, he and Deng Yingchao were finally married after a long-distance courtship of nearly five years. The couple remained childless, but adopted many orphaned children of "revolutionary martyrs"; one of the more famous was future Premier Li Peng.

After Sun's death the Kuomintang was run by a triumvirate composed of Chiang Kai-Shek, Liao Zhongkai and Wang Jingwei, but in August 1925 Liao (father of Liao Chengzhi and grandfather to Liao Hui, both prominent PRC politicians), was murdered by Nationalist agents. Chiang Kai-shek used this murder to declare martial law and consolidate right wing control of the Nationalists. On 18 March 1926, while Mikhail Borodin, the Russian comintern advisor to the United Front, was in Shanghai. Chiang created a further incident to usurp power over the communists. The commander and crew of a Kuomintang gunboat was arrested at the Whampoa docks (see Zhongshan Warship Incident). This was followed by raids on the First Army Headquarters and Whampoa Military Academy. Altogether 65 communists were arrested, including Nie Rongzhen. A state of emergency was declared and curfews were imposed. Zhou had just returned from Shantou and was also detained for 48 hours. On his release he confronted Chiang and accused him of undermining the United Front but Chiang argued that he was only breaking up a plot by the communists. When Borodin returned from Shanghai he believed Chiang’s version and rebuked Zhou. At Chiang's request Borodin turned over a list of all the members of the CCP who were also members of the Kuomintang. The only omissions from this list were the members Zhou had secretly recruited. Chiang dismissed all the rest of the CCP officers from the First Army. Wang Jingwei, considered too sympathetic to the communists, was persuaded to leave on a “study tour” in Europe. Zhou Enlai was relieved of all his duties associated with the First United front, effectively giving complete control of the United Front to Chiang Kai-Shek.

From Shanghai to Yan'an

After the Northern Expedition began, he worked as a labour agitator. In 1926, he organized a general strike in Shanghai, opening the city to the Kuomintang. When the Kuomintang broke with the Communists, Zhou managed to escape the white terror. Zhou attended a July 1927 meeting with Zhu De, He Long, Ye Jianying, Liu Bocheng, – all future marshals of the army – and Mao to decide a response to Chiang’s blood purge. Their move was the Nanchang Uprising, led by Liu and Zhou.[4]

After that attempt failed, Zhou left China for the Soviet Union to attend the Chinese Communist Party's 6th National Party Congress in Moscow, in June-July 1928.[5] He was elected Director of the Central Committee Organization Department; his ally, Li Lisan took over propaganda work. Zhou finally returned to China, after more than a year away, in 1929.

In Shanghai, Zhou began to disagree with the timing of Li Lisan's strategy of favoring rich peasants and concentrating military forces for attacks on urban centers sometime in early 1930. Zhou did not openly break with these more orthodox notions, and even tried to implement them later, in 1931, in Jiangxi. [6]

Zhou moved to the Jiangxi base area and shook up the propaganda-oriented approach to revolution by demanding that the armed forces under communist control actually be used to expand the base, rather than just to control and defend it. In December 1931, he replaced Mao as Secretary of the 1st Front Army with Xiang Ying, and made himself political commissar of the Red Army, in place of Mao. Liu Bocheng, Lin Biao and Peng Dehuai all criticized Mao's tactics at the August 1932 Ningdu Conference. [7] Under Zhou, the Red Army defeated four attacks by Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist troops.[8] Only when the Nationalists were forced to change their tactics did Zhou endorse withdrawal. Zhou Enlai was thus one of the major beneficiaries of the 1931-34 side-lining of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Tan Zhenlin, Deng Zihui, Lu Dingyi and Xiao Qingguang.

In early 1933, Bo Gu arrived with German Comintern adviser Otto Braun (a/k/a Li De)]] and took control of party affairs. Zhou at this time, apparently with strong support from party and military colleagues, undertook to reorganize and standardize the Red Army. The results were the structure that led the communists to victory:

-

Leaders Unit Designation Lin Biao, Nie Rongzhen 1st Corps Peng Dehuai, Yang Shangkun 3rd Corps Xiao Qingguang 7th Corps Xiao Ke 8th Corps Liu Binghui 9th Corps Fang Zhimin 10th Corps

In the Yan'an years, Zhou was active in promoting a united anti-Japanese front. As a result, he played a major role in the Xi'an Incident, helped to secure Chiang Kai-shek's release, and negotiated the Second CCP-KMT United Front, and coining the famous phrase "Chinese should not fight Chinese but a common enemy: the invader". Zhou spent the Sino-Japanese War as CCP ambassador to Chiang's wartime government in Chongqing and took part in the failed negotiations following World War II.

Premiership

In 1949, with the establishment of the People's Republic of China, Zhou assumed the role of Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs. In June 1953, he declared the five principles for peaceful coexistence. He headed the Communist Chinese delegation to the Geneva Conference and to the Bandung Conference (1955). He survived a covert proxy assassination attempt by the nationalist Kuomintang under the government of Chiang Kai-shek on his way to Bandung. A time bomb with an American-made MK-7 detonator was planted on a charter plane Kashmir Princess scheduled for Zhou's trip. Zhou changed planes but the rest of his crew of 16 people died. Zhou was a moderate force and a new influential voice for non-aligned states in the Cold War; his diplomacy strengthened regional ties with India, Burma, and many southeast Asian countries, as well as African states. In 1958, the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs was passed to Chen Yi but Zhou remained Prime Minister until his death in 1976.

Zhou's first major domestic focus after becoming premier was China's economy, in a poor state after decades of war. He aimed at increased agricultural production through the even redistribution of land. Industrial progress was also on his to-do list. He additionally initiated the first environmental reforms in China. In government, Mao largely developed policy while Zhou carried it out.

In 1958, Mao Zedong began the Great Leap Forward, aimed at increasing China's production levels in industry and agriculture with unrealistic targets. As a popular and practical administrator, Zhou maintained his position through the Leap. The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) was a great blow to Zhou. At its late stages in 1975, he pushed for the "four modernizations" to undo the damage caused by the campaigns.

Known as an able diplomat, Zhou was largely responsible for the re-establishment of contacts with the West in the early 1970s. He welcomed US President Richard Nixon to China in February 1972, and signed the Shanghai Communiqué.

After discovering he had cancer, he began to pass many of his responsibilities onto Deng Xiaoping. During the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, Zhou was the new target of Chairman Mao's and Gang of Four's political campaigns in 1975 by initiating "criticizing Song Jiang, evaluating the Water Margin", alluding to a Chinese literary work, using Zhou as an example of a political loser. In addition, the Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius campaign was also directed at Premier Zhou because he was viewed as one of the Gang's primary political opponents.

Reputation in popular stories

In a society where news is restricted, much weight is put on stories which cannot be verified. It was widely believed that at the Geneva Conference of 1954 U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles snubbed Zhou by publicly brushing past his outstretched hand. Whether the incident actually happened or not, President Nixon clearly believed that it had. Therefore, when he descended from Air Force One in Beijing on his visit to China, he ostentatiously and respectfully held out his hand to Zhou, who appreciated the symbolism. [9]

The clash with Russia created a number of these stories. One story had it that Zhou met Premier Nikita Khrushchev outside a meeting hall where each had denounced the other. Khrushchev, who was said to be jealous of Zhou’s cosmopolitan skills, remarked to Zhou “it’s interesting, isn’t it. I’m of working class origin while your family were landlords.” Zhou quickly replied “Yes, and we each betrayed our class!” [10]

Another such doubtful but widespread story had it that at another such encounter Khrushchev shook Zhou’s hand, then pulled out his handkerchief and wiped his hands. Zhou then pulled out his handkerchief, wiped his hands, and put the handkerchief in the nearest wastebasket. [11] This is especially interesting since apparently Richard Nixon told a similar story. He recalled that in 1954 Undersecretary of State, Walter B. Smith did not want to "break... discipline" but also did not want to slight the Chinese blatantly. Therefore, Smith held a cup of coffee in his right hand when shaking hands with Zhou. Zhou took out a white handkerchief, wiped his hand and threw the handkerchief into the garbage.

When asked for his assessment of the 1789 French Revolution, he is remembered for saying, "It is too early to say",[12] although this is also attributed to Mao.[13]

Death and reactions

Zhou was hospitalized in 1974 for bladder cancer, but continued to conduct work from the hospital, with Deng Xiaoping as the First Deputy Premier handling most of the important State Council matters. Zhou died on the morning of 8 January 1976, aged 77. He died eight months before Mao Zedong. Zhou's death brought messages of condolences from many non-aligned states that he affected during his tenure as an effective diplomat and negotiator on the world stage, and many states saw his death as a terrible loss. Zhou's body was cremated and the ashes scattered by air over hills and valleys, according to his wishes.

Inside China, the infamous Gang of Four had seen Zhou's death as an effective step forward in their political maneuvering, as the last major challenge was now gone in their plot to seize absolute power. At Zhou's funeral, Deng Xiaoping delivered the official eulogy, but later he was forced out of politics until after Mao's death.

Because Zhou was very popular with the people, many rose in spontaneous expressions of mourning across China, which the Gang considered to be dangerous, as they feared people might use this opportunity to express hatred towards them. During the Tiananmen Incident in April 1976, the Gang of Four tried to suppress mourning for the "Beloved Premier", which resulted in rioting. Anti-Gang of Four poetry was found on some wreaths that were laid, and all wreaths were subsequently taken down at the Monument to the People's Heroes. These actions, however, only further enraged the people. Thousands of armed soldiers repressed the people’s protest in Tiananmen Square, and hundreds of people were arrested. The Gang of Four blamed Deng Xiaoping for the movement and temporarily removed him from all his official positions.

Since his death, a memorial hall has been dedicated to Zhou and Deng Yingchao in Tianjin, named Tianjin Zhou Enlai Deng Yingchao Memorial Hall (traditional Chinese: 天津周恩來鄧穎超紀念館; simplified Chinese: 天津周恩来邓颖超纪念馆), and there was a statue erected in Nanjing, where in the 1940s he worked with the Kuomintang. There was an issue of national stamps commemorating the first anniversary of his death in 1977, and another in 1998 to commemorate his 100th birthday.

Assessment

Zhou Enlai is regarded as a skilled negotiator, a master of policy implementation, a devoted revolutionary, and a pragmatic statesman with infinite patience and an unusual attentiveness to detail and nuance. He was also known for his tireless and dedicated work ethic, and his unusual charm and poise in public. He is reputedly the last Mandarin bureaucrat in the Confucian tradition. Zhou's political behaviour should be viewed in light of his political philosophy as well as his personality. To a large extent, Zhou epitomized the paradox inherent in a communist politician with traditional Chinese upbringing: at once conservative and radical, pragmatic and ideological, possessed by a belief in order and harmony as well as a faith in the progressive power of rebellion and revolution.

Though a firm believer in the Communist ideal on which the People's Republic was founded, Zhou is widely believed to have moderated the excesses of Mao's radical policies within the limits of his power. It has been assumed that he protected imperial and religious sites of cultural significance (such as the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet) from the Red Guards, and shielded top-level leaders from purges.

Zhou has not shared in the personal and political charges leveled at Mao. The recent biography by Gao Wenqian implies that during the Cultural Revolution, Zhou gave in to Mao's whims rather than consistently mitigating them, and that he did not protect all of those he could have.[14] However, it is to be noted that Zhou, although sometimes giving in to Mao, was constantly having his political power undermined by the paranoid Mao.[15]

Footnotes

- ↑ Wilson, Dick, The Long March, 1935, Viking Press (New York) 1971, p. 46 and Whitson, William and Huang Chen-hsia, The Chinese High Command, A History of Communist Military Politics, 1927-71, Praeger Press (New York) 1973, p. 39

- ↑ Whitson and Huang, p. 39.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 13 and Whitson and Huang, p. 27

- ↑ Whitson, and Huang, p. 30

- ↑ Whitson and Huang, p. 39-40

- ↑ Whitson and Huang, p. 40.

- ↑ Whitson and Huang, p. 57-58

- ↑ Wilson, p. 51

- ↑ Xia Yafeng summarizes the literature on the incident, including references in Chinese, in his review of Margaret MacMillan, The Week That Shook the World, "Nixon and Kissinger/ Nixon and Mao Roundtable," H-Diplo 23, September, 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Andrew Nathan, Chinese Democracy(New York: Knopf, 1985): 176.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Article About the Communist Party of China's Leadership

- ↑ http://www.open2.net/historyandthearts/history/four_transcript_page.html

- ↑ Wenqian Gao, Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary

- ↑ Wenqian Gao, Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary

Further reading

- Han Suyin, Eldest Son: Zhou Enlai and the Making of Modern China (New York: Hill & Wang, 1994), a sympathetic general biography.

- Gao Wenqian Wannian Zhou Enlai (Zhou Enlai's Later Years) Hong Kong, Mirror Books, 2003).

- Wenqian Gao, Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary (NY: Public Affairs, 2007). Translated by Peter Rand and Lawrence R. Sullivan. A translation of the above.

See also

- History of the People's Republic of China

- Xiong Xianghui

- Third International

- Puppet state

- Satellite state

- Second International

- First international

- Anti-Comintern Pact

- Chinese Civil War

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Marco Polo Bridge Incident

- Republic of China

- Sun Yetsen

- Kuomintang

- Xinhai Revolution

- Tongmenghui

- Xingzhonghui

- Anhui clique

- Zhili clique

- Warlord era

- Fengtian clique

- Whampoa Military Academy

- Maring

- The Internationale

External links

- Zhou Enlai Biography From Spartacus Educational

- Case-Studies: Chinese Famine 1958 to 1961

- China's great famine: 40 years later Vaclav Smil, distinguished professor. University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

- HUNGRY GHOSTS Mao's Secret Famine by Jasper Becker

- Food Availability, Entitlement and the Chinese Famine of 1959-61

- Schizophrenia and the Chinese Famine of 1959-1961

- This famine was not cause by droughts or freezes

- Communal Dining and the Chinese Famine

- The Famine of 1959-1961 in China

- Long-Term Effects Of The 1959-1961 China Famine: Mainland China and Hong Kong

- One hundred years of famine - a pause for reflection

- The demographic consequences of female infanticide, as practiced in China in periods of famine

| Preceded by Wang Ming |

Head of CPC Central United Front Department 1947 – 1948 |

Succeeded by Li Weihan |

| Preceded by None |

Foreign Minister of the People's Republic of China 1949–1958 |

Succeeded by Chen Yi |

| Preceded by None |

Premier of the State Council 1949–1976 |

Succeeded by Hua Guofeng |

| Preceded by Mao Zedong |

Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference 1954—1976 |

Succeeded by Deng Xiaoping |

|

|||||

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||