Zaire

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Republic of Zaire (pronunciation: [zaː.ɪr]; French: République du Zaïre) was the name of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo between 27 October 1971, and 17 May 1997. The name of Zaire derives from the Portuguese: Zaire, itself an adaptation of the Kongo word nzere or nzadi, or "the river that swallows all rivers",[1] and is often still used to refer to that state, perhaps because "Zaire" is much shorter than "Democratic Republic of the Congo", and avoids confusion with the nearby "Republic of the Congo".

Unrest and rebellion plagued the government until 1965, when Lieutenant General Mobutu Sese Seko, by then commander-in-chief of the national army, seized control of the country and declared himself president for five years. See Congo Crisis. Mobutu quickly consolidated his power and was elected unopposed as president in 1970.

Contents |

The Second Republic

In retrospective justification of his 1965 seizure of power, Mobutu later summed up the record of the First Republic as one of "chaos, disorder, negligence, and incompetence." Rejection of the legacy of the First Republic went far beyond rhetoric. In the first two years of its existence, the new regime turned to the urgent tasks of political reconstruction and consolidation. Creating a new basis of legitimacy for the state, in the form of a single party, came next in Mobutu's order of priority. A third imperative was to expand the reach of the state in the social and political realms, a process that began in 1970 and culminated in the adoption of a new constitution in 1974. By 1976, however, this effort had begun to generate its own inner contradictions, thus paving the way for the resurrection of a Bula Matari ("the rocks breaker one") system of repression and brutality.

Self-proclaimed Father of the Nation

From 1965, Mobutu Sese Seko dominated the political life of Congo (Léopoldville), restructuring the state on more than one occasion, and claiming the title of "Father of the Nation." Any discussion of Zaire's political structures and processes must therefore be based on an understanding of the man who literally gave the country its name.

Joseph-Désiré Mobutu was born in the town of Lisala, on the Congo River, on 14 October 1930. His father, Albéric Gbemani, was a cook for a colonial magistrate in Lisala. Despite his birthplace, however, Mobutu belonged not to the dominant ethnic group of that region but rather to the Ngbandi, a small ethnic community whose domain lay far to the north, along the border with the Central African Republic.

Mobutu referred frequently both to his humble background as the son of a cook and to the renown of his father's uncle, a warrior and diviner from the village of Gbadolite. In addition to his official name, Mobutu was also given the name of his great-uncle, Sese Seko Nkuku wa za Banga, meaning "all-conquering warrior, who goes from triumph to triumph." When, under the authenticity policy of the early 1970s, Zairians were obliged to adopt "authentic" names, Mobutu dropped Joseph-Désiré and became Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga--or, more commonly, Mobutu Sese Seko (see Zairianization, Radicalization, and Retrocession, this section).

Mobutu, who had completed four years of primary school in Léopoldville, took seven more years to reach the secondary level, moving in and out of different schools. He had frequent conflicts with the Roman Catholic missionaries whose schools he attended, and in 1950, at the age of nineteen, he was definitively expelled. A seven-year disciplinary conscription into the Force Publique followed.

Military service proved crucial in shaping Mobutu's career. Unlike many recruits, he spoke excellent French, which quickly won him a desk job. By November 1950, he was sent to the school for noncommissioned officers, where he came to know many members of the military generation who would assume control of the army after the flight of the Belgian officers in 1960. By the time of his discharge in 1956, Mobutu, had risen to the rank of sergeant-major, the highest rank open to Congolese. He also had begun to write newspaper articles under a pseudonym.

Mobutu returned to civilian life just as decolonization began to seem possible. His newspaper articles had brought him to the attention of Pierre Davister, a Belgian editor of the Léopoldville paper L'Avenir (The Future.) At that time, a European patron was of enormous benefit to an ambitious Congolese; under Davister's tutelage, Mobutu became an editorial writer for the new African weekly, Actualités Africaines. Davister later would provide valuable services by giving favorable coverage to the Mobutu regime as editor of his own Belgian magazine, Spécial.

Mobutu thus acquired visibility among the emergent African elite of Léopoldville. Yet one portal to status in colonial society remained closed to him: full recognition as an évolué depended upon approval by the Roman Catholic Church. Denied this recognition, Mobutu rejected the church.

During 1959-60, politically ambitious young Congolese were busy constructing political networks for themselves. Residence in Belgium prevented Mobutu from the path of many of his peers at home, who were building ethno-regional clientèles. But their approach would have been unpromising for him in any case, since the Ngbandi were a small and peripheral community, and among the so called Ngala (Lingala-speaking immigrants in Léopoldville) such figures as Jean Bolikango were potential opponents. Mobutu pursued another route, as Belgian diplomatic, intelligence, and financial interests sought clients among the Congolese students and interns in Brussels.

Fatefully, Mobutu also had met Patrice Lumumba, when the latter arrived in Brussels. He allied himself with Lumumba (whose school background, like that of Mobutu, inclined him to anticlericalism), when the Congolese National Movement (Mouvement National Congolais - MNC) split into two wings identified, respectively, with Lumumba and Albert Kalonji. By early 1960, Mobutu had been named head of the MNC-Lumumba office in Brussels. He attended the Round Table Conference on independence held in Brussels in January 1960 and returned home only three weeks before Independence Day, 30 June. When the army mutinied against its Belgian officers, Mobutu was a logical choice to help fill the void. Lumumba, elected prime minister in May 1960, named as commander in chief a member of his own ethnic group, Victor Lundula, but Mobutu was Lumumba's choice as chief of staff.

During the crucial period of July-August 1960, Mobutu built up "his" national army by channeling foreign aid to units loyal to him, by exiling unreliable units to remote areas, and by absorbing or dispersing rival armies. He tied individual officers to him by controlling their promotion and the flow of money for payrolls. Lundula, older and less competitive, apparently did little to prevent Mobutu.

After President Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba as premier on 5 September, and Lumumba sought to block this action through parliament, Mobutu staged his first coup on 14 September. On his own authority (but with United States backing), he installed an interim government, the so-called College of Commissioners, composed primarily of university students and graduates, which replaced parliament for six months in 1960-61.

During the next four years, as weak civilian governments rose and fell in Léopoldville, real power was held behind the scenes by the "Binza Group," a group of Mobutu supporters named for the prosperous suburb where its members lived.

When in 1965, as in 1960, the division of power between president and prime minister led to a stalemate and threatened the country's stability, Mobutu again seized power (again with United States backing). Unlike the first time, however, Mobutu assumed the presidency, rather than remaining behind the scenes.

In an attempt at political reconstruction, Mobutu then undertook the task of launching a more broadly based movement--a movement which, in Mobutu's words, "will be animated by the Chief of State himself, and of which the CVR is not at all the embryo."

Quest for legitimacy

By 1967, Mobutu had consolidated his rule and proceeded to give the country a new constitution and a single party. The new constitution was submitted to popular referendum in June 1967 and approved by 98 percent of those voting. It provided that executive powers be centralized in the president, who was to be head of state, head of government, commander in chief of the armed forces and the police, and in charge of foreign policy. The president was to appoint and dismiss cabinet members and determine their areas of responsibility. The ministers, as heads of their respective departments, were to execute the programs and decisions of the president. The president also was to have the power to appoint and dismiss the governors of the provinces and the judges of all courts, including those of the Supreme Court of Justice.

The bicameral parliament was replaced by a unicameral legislative body called the National Assembly. Governors of provinces were no longer elected by provincial assemblies but appointed by the central government. The president had the power to issue autonomous regulations on matters other than those pertaining to the domain of law, without prejudice to other provisions of the constitution. Under certain conditions, the president was empowered to govern by executive order, which carried the force of law.

But the most far-reaching change was the creation of the Popular Movement of the Revolution (Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution — MPR) on 17 April 1967, marking the emergence of "the nation politically organized." Rather than being the emanation of the state, the state was henceforth defined as the emanation of the party. Thus, in October 1967 party and administrative responsibilities were merged into a single framework, thereby automatically extending the role of the party to all administrative organs at the central and provincial levels, as well as to the trade unions, youth movements, and student organizations. In short, the MPR became the sole legitimate vehicle for participating in the political life of the country and all Zairians were considered to be members by birth. Or, as one official put it, "the MPR must be considered as a Church and its Founder as its Messiah."

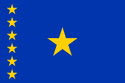

The doctrinal foundation was disclosed shortly after its birth, in the form of the Manifesto of N'Sele (so named because it was issued from the president's rural residence at N'Sele, sixty kilometers upriver from Kinshasa), made public in May 1967. Nationalism, revolution, and authenticity were identified as the major themes of what came to be known as "Mobutism". Nationalism implied the achievement of economic independence. Revolution, described as a "truly national revolution, essentially pragmatic," meant "the repudiation of both capitalism and communism. "Neither right nor left" thus became one of the legitimizing slogans of the regime, along with "authenticity." The concept of authenticity was derived from the MPR's professed doctrine of "authentic Zairian nationalism and condemnation of regionalism and tribalism." Mobutu defined it as being conscious of one's own personality and one's own values and of being at home in one's culture. In line with the dictates of authenticity, the name of the country was changed to the Republic of Zaire in October 1971, and that of the armed forces to Zairian Armed Forces (Forces Armées Zaïroises--FAZ). This decision was curious, given that the name Congo, which referred both to the river Congo and to the ancient Kongo Empire, was fundamentally "authentic" to pre-colonial African roots, while Zaire is in fact a Portuguese corruption of another African word, Nzere ("river", by Nzadi o Nzere, "the river that swallows all the other rivers", another name of the Congo river). General Mobutu became Mobutu Sese Seko and forced all his citizens to adopt African names and many cities were also renamed. Some of the conversions are as follows:

- Léopoldville became Kinshasa

- Stanleyville became Kisangani

- Elisabethville became Lubumbashi

- Jadotville became Likasi

- Albertville became Kalemie

Additionally, the zaïre was introduced to replace the franc as the new national currency. 100 makuta (singular likuta) equaled one zaïre. The likuta was also divided into 100 sengi. However this unit was worth very little, so the smallest coin was for 10 sengi. As a result, it was common practice to write cash amounts with three zeros after the decimal place, even after inflation had greatly devalued the currency. Many other geographic name changes had already taken place, between 1966 and 1971. The adoption of Zairian, as opposed to Western or Christian, names in 1972 and the abandonment of Western dress in favor of the wearing of the abacost were subsequently promoted as expressions of authenticity.

Authenticity provided Mobutu with his strongest claim to philosophical originality. So far from implying a rejection of modernity, authenticity is perhaps best seen as an effort to reconcile the claims of the traditional Zairian culture with the exigencies of modernization. Exactly how this synthesis was to be accomplished remained unclear, however. What is beyond doubt is Mobutu's effort to use the concept of authenticity as a means of vindicating his own brand of leadership. As he himself stated, "in our African tradition there are never two chiefs … That is why we Congolese, in the desire to conform to the traditions of our continent, have resolved to group all the energies of the citizens of our country under the banner of a single national party."

Critics of the regime were quick to point out the shortcomings of Mobutism as a legitimizing formula, in particular its selfserving qualities and inherent vagueness; nonetheless, the MPR's ideological training center, the Makanda Kabobi Institute, took seriously its assigned task of propagating through the land "the teachings of the Founder-President, which must be given and interpreted in the same fashion throughout the country." Members of the MPR Political Bureau, meanwhile, were entrusted with the responsibility of serving as "the repositories and guarantors of Mobutism."

Quite aside from the merits or weaknesses of Mobutism, the MPR drew much of its legitimacy from the model of the overarching mass parties that had come into existence in Africa in the 1960s, a model which had also been a source of inspiration for the MNC-Lumumba. It was this Lumumbist heritage which the MPR tried to appropriate in its effort to mobilize the Zairian masses behind its founder-president. Intimately tied up with the doctrine of Mobutism was the vision of an all-encompassing single party reaching out to all sectors of the nation.

Authoritarian expansion

Translating the concept of "the nation politically organized" into reality implied a major expansion of state control of civil society. It meant, to begin with, the incorporation of youth groups and worker organizations into the matrix of the MPR. In July 1967, the Political Bureau announced the creation of the Youth of the Popular Revolutionary Movement (Jeunesse du Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution--JMPR), following the launching a month earlier of the National Union of Zairian Workers (Union Nationale des Travailleurs Zaïrois--UNTZA), which brought together into a single organizational framework three preexisting trade unions. Ostensibly, the aim of the merger, in the terms of the Manifesto of N'Sele, was to transform the role of trade unions from "being merely a force of confrontation" into "an organ of support for government policy," thus providing "a communication link between the working class and the state." Similarly, the JMPR was to act as a major link between the student population and the state. In reality, the government was attempting to bring under its control those sectors where opposition to the regime might be centered. By appointing key labor and youth leaders to the MPR Political Bureau, the regime hoped to harness syndical and student forces to the machinery of the state. Nevertheless, as has been pointed out by numerous observers, there is little evidence that co-optation succeeded in mobilizing support for the regime beyond the most superficial level.

The trend toward co-optation of key social sectors continued in subsequent years. Women's associations were eventually brought under the control of the party, as was the press, and in December 1971 Mobutu proceeded to emasculate the power of the churches. From then on, only three churches were recognized: the Church of Christ in Zaire (L'Église du Christ au Zaïre), the Kimbanguist Church, and the Roman Catholic Church. Nationalization of the universities of Kinshasa and Kisangani, coupled with Mobutu's insistence on banning all Christian names and establishing JMPR sections in all seminaries, soon brought the Roman Catholic Church and the state into conflict. Not until 1975, and after considerable pressure from the Vatican, did the regime agree to tone down its attacks on the Roman Catholic Church and return some of its control of the school system to the church. Meanwhile, in line with a December 1971 law, which allowed the state to dissolve "any church or sect that compromises or threatens to compromise public order," scores of unrecognized religious sects were dissolved and their leaders jailed.

Mobutu was careful also to suppress all institutions that could mobilize ethnic loyalties. Avowedly opposed to ethnicity as a basis for political alignment, he outlawed such ethnic associations as the Association of Lulua Brothers (Association des Lulua Frères), which had been organized in Kasai in 1953 in reaction to the growing political and economic influence in Kasai of the rival Luba people, and Liboke lya Bangala (literally, "a bundle of Bangala"), an association formed in the 1950s to represent the interests of Lingala speakers in large cities. It helped Mobutu that his ethnic affiliation was blurred in the public mind. Nevertheless, as dissatisfaction arose, ethnic tensions surfaced again.

Running parallel to the efforts of the state to control all autonomous sources of power, important administrative reforms were introduced in 1967 and 1973 to strengthen the hand of the central authorities in the provinces. The central objective of the 1967 reform was to abolish provincial governments and replace them with state functionaries appointed by Kinshasa. The principle of centralization was further extended to districts and territories, each headed by administrators appointed by the central government. The only units of government that still retained a fair measure of autonomy--but not for long--were the so-called local collectivities, i.e., chiefdoms and sectors (the latter incorporating several chiefdoms). The unitary, centralized state system thus legislated into existence bore a striking resemblance to its colonial antecedent, except that from July 1972 provinces were called regions.

With the January 1973 reform, another major step was taken in the direction of further centralization. The aim, in essence, was to operate a complete fusion of political and administrative hierarchies by making the head of each administrative unit the president of the local party committee. Furthermore, another consequence of the reform was to severely curtail the power of traditional authorities at the local level. Hereditary claims to authority would no longer be recognized; instead, all chiefs were to be appointed and controlled by the state via the administrative hierarchy. By then, the process of centralization had theoretically eliminated all preexisting centers of local autonomy.

The analogy with the colonial state becomes even more compelling if we take into account the introduction in 1973 of "obligatory civic work" (locally known as Salongo after the Lingala term for work), in the form of one afternoon a week of compulsory labor on agricultural and development projects. Officially described as a revolutionary attempt to return to the values of communalism and solidarity inherent in the traditional society, Salongo was intended to mobilize the population into the performance of collective work "with enthusiasm and without constraint." But, in fact Salongo was forced labor. The conspicuous lack of popular enthusiasm for Salongo led to widespread resistance and foot dragging, causing many local administrators to look the other way. Although failure to comply carried penalties of one month to six months in jail, by the late 1970s most Zairians avoided their Salongo obligations. By resuscitating one of the most bitterly resented features of the colonial state, obligatory civic work contributed in no small way to the erosion of legitimacy suffered by the Mobutist state.

Mobutist Nomenklatura

In the 1970s and 1980s, Mobutu's government relied on a selected pool of technocrats from which the Head of State drew, and periodically rotated, competent individuals. They comprised the Executive Council and led the full spectrum of Ministries or, as they were then called, State Commissariats. Among these individuals were internationally respected appointees such as Djamboleka Lona Okitongono who was named Secretary of Finance, under Citizen Namwisi (Minister of Finance), and later became President of OGEDEP, the National Debt Management Office. Ultimately, Djamboleka became Governor of the Bank of Zaire in the final stage of Mobutu's government. His progress was fairly typical of the rotational pattern established by the Head of State, Mobutu, who, incidentally retained the most sensitive ministerial portfolios, such as Defense, for himself.

"Zairianization"

Relative peace and stability prevailed until 1977 and 1978 when Katangan rebels, based in Angola, launched a series of invasions, sometimes known as Shaba I, into the Shaba (Katanga) region. The rebels were driven out with the aid of French and Belgian paratroopers.

During the 1980s, Zaire remained a one-party state. Although Mobutu successfully maintained control during this period, opposition parties, most notably the Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS), were active. Mobutu's attempts to quell these groups drew significant international criticism.

As the Cold War came to a close, internal and external pressures on Mobutu increased. In late 1989 and early 1990, Mobutu was weakened by a series of domestic protests, by heightened international criticism of his regime's human rights practices, by a faltering economy, and by government corruption, most notably his massive embezzlement of government funds for personal use.

In May 1990 Mobutu agreed to the principle of a multi-party system with elections and a constitution. As details of a reform package were delayed, soldiers began looting Kinshasa in September 1991 to protest their unpaid wages. Two thousand French and Belgian troops, some of whom were flown in on U.S. Air Force planes, arrived to evacuate the 20,000 endangered foreign nationals in Kinshasa.

In 1992, after previous similar attempts, the long-promised Sovereign National Conference was staged, encompassing over 2,000 representatives from various political parties. The conference gave itself a legislative mandate and elected Archbishop Laurent Monsengwo as its chairman, along with Étienne Tshisekedi wa Mulumba, leader of the UDPS, as prime minister. By the end of the year Mobutu had created a rival government with its own prime minister. The ensuing stalemate produced a compromise merger of the two governments into the High Council of Republic-Parliament of Transition (HCR-PT) in 1994, with Mobutu as head of state and Kengo Wa Dondo as prime minister. Although presidential and legislative elections were scheduled repeatedly over the next 2 years, they never took place.

First Congo War

By 1996, tensions from the neighboring Rwanda war and genocide had spilled over to Zaire (see History of Rwanda). Rwandan Hutu militia forces (Interahamwe), who had fled Rwanda following the ascension of an RPF-led government, had been using Hutu refugees camps in eastern Zaire as a basis for incursion against Rwanda. These Hutu militia forces soon allied with the Zairian armed forces (FAZ) to launch a campaign against Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire. In turn, these Tutsis formed a militia to defend themselves against attacks. When the Zairian government began to escalate its massacres in November 1996, the Tutsi militias erupted in rebellion against Mobutu starting what would become known as the First Congo War.

The Tutsi militia was soon joined by various opposition groups and supported by several countries, including Rwanda and Uganda. This coalition, led by Laurent-Desire Kabila, became known as the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL). The AFDL, now seeking the broader goal of ousting Mobutu, made significant military gains in early 1997. Following failed peace talks between Mobutu and Kabila in May 1997, Mobutu fled the country, and Kabila marched unopposed to Kinshasa on 20 May. Kabila named himself president, consolidated power around himself and the AFDL, and reverted the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Standards and abbreviations

In computing, Zaire's top level domain was ".zr". It has since changed to ".cd".[1]

See also

- Belgian Congo

References

- This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

- Zaire

- All you need to know about Zaire's election

- ↑ Peter Forbath, The River Congo, p. 19

|

|||||||||||||||||