Cantonese

| Cantonese 粵語 / 粤语 Yuhtyúh/ 廣東話/广东话 gwong dung waa |

||

|---|---|---|

| Spoken in: | China; Malaysia and countries with overseas Chinese originating from Cantonese-speaking parts of China | |

| Region: | the Pearl River Delta (central Guangdong; Hong Kong, Macau); the eastern and southern Guangxi; parts of Hainan; Malaysia (Sandakan, Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur); United Kingdom; Vancouver; Toronto; San Francisco, New York City | |

| Total speakers: | 70 million (2000)[1] | |

| Language family: | Sino-Tibetan Chinese Cantonese |

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | Hong Kong and Macau ("Chinese" is official; Cantonese and Mandarin are the forms used in government). Recognised regional language in Suriname. | |

| Regulated by: | No official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | zh | |

| ISO 639-2: | chi (B) | zho (T) |

| ISO 639-3: | yue | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Cantonese, known technically as Yue [2] or Yuet (粵語; Mandarin Yuè Yǔ; Cantonese (Yale) Yuht Yúh, (jyutping) Jyut6 Jyu5), is a primary branch of Chinese. Colloquially, it is also known as 廣東話/广东话 (Cantonese transcription: gwong2 dung1 waa6; Mandarin: Guǎngdōng Huà). The name "Cantonese" is commonly used in a narrower sense for the Guangzhou dialect, which is the prestige dialect of Cantonese in the broader sense.

The issue of whether Cantonese in the broader sense should be regarded as a language in its own right or as a dialect of a Chinese language is controversial. Like the other primary branches of Chinese, Cantonese is considered to be a dialect of a single Chinese language for ethnic and cultural reasons, but it is also considered a language in its own right because it is mutually unintelligible with other varieties of Chinese. See Identification of the varieties of Chinese.

The exact number of Cantonese speakers is unknown due to a lack of statistics and census data. The areas with the highest concentration of speakers are Guangdong, some parts of Guangxi in southern mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau, with Cantonese-speaking minorities in Southeast Asia, Canada, and the United States.[3]

Contents |

Guangzhou dialect

There are numerous Cantonese dialects. The Canton–Hong Kong dialect, also known as the Cantonese dialect, is the prestige dialect and a de facto official language of Hong Kong. It is the most widely spoken dialect, spoken in Canton, Hongkong, and Macau, and is is a lingua franca of not just Guangdong province, but also the overseas Cantonese-speaking diaspora.

Names

To avoid the ambiguity of the English name "Cantonese", linguists generally refer to the entire language as "Yue",[4] though "Cantonese dialects" in the plural is found in more colloquial contexts.[5] Cantonese in the narrow sense is likewise sometimes called "Canton dialect" or "Guangzhou dialect".[6] People of Hong Kong, Macau and Cantonese immigrants abroad usually call it 廣東話 "Canton province speech".[7]

Dialects

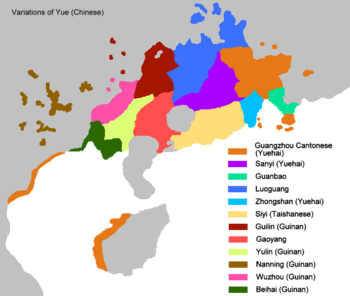

There are four major dialect groups of Cantonese:

- Cantonese, or Yuehai 粵海, which includes the Canton dialect spoken in Guangzhou 廣州, Hong Kong 香港 and Macau 澳門 as well as the dialects of Zhongshan 中山, and Dongguan 東莞

- Sìyì (四邑, sei yap), exemplified by Taishan dialect 台山, which was ubiquitous in American Chinatowns before ca 1970

- Gaoyang dialect, spoken in Yangjiang 陽江

- Guinan (桂南, from [Southern Guangxi) spoken widely in Guangxi 廣西.

In Hainan 海南 Province, two unclassified dialects are spoken which may be closely related to Cantonese, the Mai dialect and the Danzhou dialect[8]. The name "Cantonese" generally refers to the Yuehai dialect.

Besides Cantonese, there are three other primary branches of Chinese spoken in Guangdong Province— Standard Mandarin, which is used for official occasions, education, the media, and as a national lingua franca; Min Nan (Southern Min), spoken in the eastern regions bordering Fujian 福建 , such as Chaozhou 潮州 and Shantou 汕頭; and Hakka 客家, the language of the Hakka people. Standard Mandarin is mandatory through the state education system, but in Cantonese-speaking households, Cantonese-language media (Hong Kong films, television serials, and Cantopop), isolation from the other regions of China, local identity, and the non-Mandarin speaking Cantonese diaspora in Hong Kong and abroad give the language a unique identity. Most wuxia 武俠 films from Canton are filmed originally in Cantonese and then dubbed or subtitled in Mandarin, English, or both.

Phonology

- See Canton dialect and Taishanese for a discussion of the sounds those dialects.

Cantonese development and usage

Officially Standard Mandarin (Putonghua or guoyu) is the standard language of mainland China and Taiwan and is taught nearly universally as a supplement to local languages such as Cantonese in Guangdong. Cantonese and Standard Mandarin are the de facto official languages of Hong Kong and Macau, though legally the official language is "Chinese". Cantonese is also one of the main languages in many overseas Chinese communities including Australia, Southeast Asia, North America, and Europe. Many of these emigrants and/or their ancestors originated from Guangdong. In addition, these immigrant communities formed before the widespread use of Mandarin, or they are from Hong Kong where Mandarin is not commonly used. The prestige dialect of Cantonese is the Guangzhou / Cantonese dialect. In Hong Kong, colloquial Cantonese often incorporates English words due to historical British influences.

In some ways, Cantonese is a more conservative language than Mandarin, and in other ways it is not. For example, Cantonese has retained consonant endings from older varieties of Chinese that have been lost in Mandarin, but it has merged some vowels from older varieties of Chinese.

The Taishan dialect, which in the U.S. nowadays is heard mostly spoken by Chinese actors in old American TV shows and movies (e.g. Hop Sing on Bonanza), is more conservative than Cantonese. It has preserved the initial /n/ sound of words, whereas many post-World War II-born Hong Kong Cantonese speakers have changed this to an /l/ sound ("ngàuh lām" instead of "ngàuh nām" for "beef brisket" 牛腩) and more recently drop the "ng-" initial (so that it changes further to "àuh lām"); this seems to have arisen from some kind of street affectation as opposed to systematic phonological change. The common word for "who" in Taishan is "sŭe" (誰), which is the same character used in classical Chinese, whereas Cantonese has changed it to "bīngo" (邊個).

Cantonese sounds quite different from Mandarin, mainly because it has a different set of syllables. The rules for syllable formation are different; for example, there are syllables ending in non-nasal consonants (e.g. "lak"). It also has different tones and more of them than Mandarin. Cantonese is generally considered to have 8 tones, the choice depending on whether a traditional distinction between a high-level and a high-falling tone is observed; the two tones in question have largely merged into a single, high-level tone, especially in Hong Kong Cantonese, which has tended to simplify traditional Chinese tones. Many (especially older) descriptions of the Cantonese sound system record a higher number of tones, 9. However, the extra tones differ only in that they end in p, t, or k; otherwise they can be modeled identically.[9]

Cantonese preserves many syllable-final sounds that Mandarin has lost or merged. For example, the characters 裔, 屹, 藝, 艾, 憶, 譯, 懿, 誼, 肄, 翳, 邑, and 佚 are all pronounced "yì" in Mandarin, but they are all different in Cantonese (Cantonese jeoih, ngaht, ngaih, ngaaih, yìk, yihk, yi, yìh, si, ai, yap, and yaht, respectively). Like Hakka and Min Nan, Cantonese has preserved the final consonants [-m, -n, -ŋ -p, -t, -k] from Middle Chinese, while the Mandarin final consonants have been reduced to [-n, -ŋ]. But unlike any other modern Chinese dialects, the final consonants of Cantonese match those of Middle Chinese with very few exceptions. For example, lacking the syllable-final sound "m"; the final "m" and final "n" from older varieties of Chinese have merged into "n" in Mandarin, e.g. Cantonese "taahm" (譚) and "tàahn" (壇) versus Mandarin tán; "yìhm" (鹽) and "yìhn" (言) versus Mandarin yán; "tìm" (添) and "tìn" (天) versus Mandarin tiān; "hùhm" (含) and "hòhn" (寒) versus Mandarin hán. The examples are too numerous to list. Furthermore, nasals can be independent syllables in Cantonese words, e.g. Cantonese "ńgh" (五) "five," and "m̀h" (唔) "not".

Differences also arise from Mandarin's relatively recent sound changes. One change, for example, palatalized [kʲ] with [tsʲ] to [tɕ], and is reflected in historical Mandarin romanizations, such as Peking (Beijing), Kiangsi (Jiangxi), and Fukien (Fujian). This distinction is still preserved in Cantonese. For example, 晶, 精, 經 and 京 are all pronounced as "jīng" in Mandarin, but in Cantonese, the first pair is pronounced "jīng", and the second pair "gīng".

A more drastic example, displaying both the loss of coda plosives and the palatization of onset consonants, is the character (學), pronounced *ɣæwk in Middle Chinese. Its modern pronunciations in Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkien, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese are "hohk", "hók" (pinjim), "ha̍k" (Pe̍h-ōe-jī), học (although a Sino-Vietnamese word, it is used in daily vocabulary), "학" (hak) (Sino-Korean), and "gaku" (Sino-Japanese), respectively, while the pronunciation in Mandarin is xué [ɕyɛ].

However, the Mandarin vowel system is somewhat more conservative than that of Cantonese, in that many diphthongs preserved in Mandarin have merged or been lost in Cantonese. Also, Mandarin makes a three-way distinction among alveolar, alveopalatal, and retroflex fricatives, distinctions that are not made by modern Cantonese. For example, jiang (將) and zhang (張) are two distinct syllables in Mandarin or old Cantonese, but in modern Cantonese they have the same sound, "jeung1". The loss of distinction between the alveolar and the alveolopalatal sibilants in Cantonese occurred in the mid-19th centuries and was documented in many Cantonese dictionaries and pronunciation guides published prior to the 1950s. A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect by Williams (1856), writes: The initials "ch" and "ts" are constantly confounded, and some persons are absolutely unable to detect the difference, more frequently calling the words under "ts" as "ch", than contrariwise. A Pocket Dictionary of Cantonese by Cowles (1914) adds: "s" initial may be heard for "sh" initial and vice versa.

There are clear sound correspondences in the tones. For example, a fourth-tone (low falling tone) word in Cantonese is usually second tone (rising tone) in Mandarin.

This can be partly explained by their common descent from Middle Chinese (spoken), still with its different dialects. One way of counting tones gives Cantonese nine tones, Mandarin four, and Middle Chinese eight. Within this system, Mandarin merged the so-called "yin" and "yang" tones except for the Ping (平, flat) category, while Cantonese not only preserved these, but split one of them into two over time. Also, within this system, Cantonese is the only Chinese language known to have split its tones rather than merge them since the time of Late Middle Chinese.

Relation to Classical Chinese

Since the pronunciation of all modern varieties of Chinese are different from Old Chinese or other forms of historical Chinese (such as Middle Chinese), characters that once rhymed in poetry may no longer (e.g. rhyming occurring sometimes in Min, Cantonese, and rarely in Mandarin, or vice versa). Poetry and other rhyme-based writing thus becomes less coherent than the original reading must have been. However, some modern Chinese dialects have certain phonological characteristics that are closer to the older pronunciations than others, as shown by the preservation of certain rhyme structures. Some believe wenyan literature, especially poetry, sounds better when read in certain dialects believed to be closer to older pronunciations, such as Cantonese or Southern Min, or the Wenzhou dialect.

Cantonese outside China

Historically, the majority of the overseas Chinese have originated from just two provinces; Fujian and Guangdong. This has resulted in the overseas Chinese having a far higher proportion of Fujian and Guangdong languages/dialect speakers than Chinese speakers in China as a whole. More recent emigration from Fujian and Hong Kong have continued this trend.

The largest number of Cantonese speakers outside mainland China and Hong Kong are in south east Asia, however speakers of Min dialects are predominate among the overseas Chinese in south east Asia. The Cantonese spoken in Singapore and Malaysia is also known to have borrowed substantially from Malay and other languages

United Kingdom

The majority of Cantonese speakers in the UK have origins from the former British colony of Hong Kong and speak the Canton/Hong Kong dialect, although many are in fact from Hakka-speaking families and are bilingual in Hakka. There are also Cantonese speakers from south east Asian countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, as well as from Guangdong in China itself. Today an estimated 300,000 British people have Cantonese as a mother tongue/first language, this represents 0.5% of the total UK population and 1% of the total overseas Cantonese speakers[10]

United States of America

For the last 150 years, Guangdong Province has been the place of origin of most Chinese emigrants to western countries; one coastal county, Taishan (or Tóisàn, where the Sìyì or sei yap dialect of Cantonese is spoken), alone may have been the home to more than 60% of Chinese immigrants to the US before 1965. As a result, Guangdong dialects such as sei yap (the dialects of Taishan, Enping, Kaiping and Xinhui counties) and what is now called mainstream Cantonese (with a heavy Hong Kong influence) have been the major Cantonese dialects spoken abroad, particularly in the USA.

The Taishan dialect, one of the sei yap or siyi (四邑) dialects that come from Guangdong counties that were the origin of the majority of Exclusion-era Guangdong Chinese emigrants to the USA, continues to be spoken both by recent immigrants from Taishan and even by third-generation Chinese Americans of Taishan ancestry alike.

The dialect of Zhongshan in Pearl River Delta is spoken by many Chinese immigrants in Hawaii, and some in San Francisco and in the Sacramento River Delta (see Locke, California); it is much closer to Canton dialect than Taishanese, but has "flatter" tones in pronunciation than Cantonese. Cantonese is the third most widely spoken non-English language in the United States.[11] The currently most popular romanization for learning Cantonese in the United States is Yale Romanization.

The dialectal situation is now changing in the United States; recent Chinese emigrants originate from many different areas including mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Recent immigrants from mainland China and Taiwan in the U.S. all speak Standard Mandarin (putonghua/guoyu) with varying degrees of fluency, and their native local language/dialect, such as Min (Hokkien and other Fujian dialects), Wu, Mandarin, Cantonese etc. As a result Standard Mandarin is increasingly becoming more common as the Chinese lingua franca among overseas Chinese.

History

Qin and Han

In ancient China, Guangdong was called Nanyue, and very few Han people lived there. Therefore, the Chinese language was not widely spoken there at that time. However, in the Qin Dynasty Chinese troops moved south and conquered the Baiyue territories, and thousands of Han people began settling in the Lingnan area. This migration led to the Chinese language being spoken in the Lingnan area. After Zhào Tuó was made the Duke of Nanyue by the Han Dynasty and given authority over the Nanyue region, many Han people entered the area and lived together with the Nanyue population, consequently affecting the livelihood of the Nanyue people as well as stimulating the spread of the Chinese language. Although Han Chinese settlements and their influences soon dominated, some indigenous Nanyue population did not escape from the region. Today, the degree of interaction between Han Chinese and the indigenous population remains vague due to the lack of historical records.

Sui

In the Sui Dynasty, Zhongyuan was in a period of war and discontent, and many people moved southwards to avoid war, forming the first mass migration of Han people into the South. As the population in the Lingnan area dramatically rose, the Chinese language in the south developed significantly. Thus, the Cantonese language began to develop more significant differences with central Chinese.

Tang

As the Han population in the Guangdong area continued to rise during the Tang Dynasty, some indigenous people living in the south had been culturally assimilated by the Han population, while others moved to other regions (such as Guangxi), developing their own dialects. At the time, Cantonese was affected by central Chinese and became more standardized, but it further developed a more independent language structure, vocabulary, and grammar.

Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing

In the Song Dynasty, the differences between central Chinese and Cantonese became more significant, and the languages became more independent of one another. During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, Cantonese evolved still further, developing its own characteristics.

Mid to Late Qing

In the late Qing, the dynasty had gone through a period of maritime ban under the Hai jin. Guangzhou remained one of the only cities that allowed trading with foreign countries, since the trade chamber of commerce was established there.[12] Therefore, some foreigners learned Cantonese and some Imperial government officials spoke Cantonese, making the language very popular in Cantonese-speaking Guangzhou. Also, the European control of Macau and Hong Kong had increased the exposure of Cantonese to the world.

20th century

In the Cantonese-speaking region of mainland China, Mandarin is used for official purposes while Cantonese is used more informal situations.

In Hong Kong, Hong Kong Cantonese is the main and dominant form of spoken Chinese and is used in education, the government, public life, the media and entertainment (e.g. Hong Kong cinema), and in business dealings with Cantonese-speaking overseas Chinese communities.

Nowadays, due to Putonghua (Mandarin) being the medium of education on the mainland, many youngsters in the Cantonese speaking region in mainland China do not know specific historical and scientific vocabularies in Cantonese but do know social, cultural, entertainment, commercial, trading, and all other vocabularies. Cantonese is widely spoken and learned by overseas Chinese of Guangdong and Hong Kong origin.

The popularity of Cantonese-language media and entertainment from Hong Kong has led to a wide and frequent exposure of Cantonese to large portions of China and the rest of Asia. Cantopop and the Hong Kong film industry are prominent examples of modern Cantonese language media.

See also

- Standard Cantonese

- Hong Kong Government Cantonese Romanisation

- Standard Cantonese Pinyin

- Jyutping (LSHK)

- Yale Romanization#Cantonese

- Written Cantonese

- Cantonese grammar

- Chinese written language

- Chinese input methods for computers

References

- ↑ Li, Ping. [2006] (2006). The Handbook of East Asian Psycholinguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521833337. pg 13.

- ↑ The Ethnologue entry lists it as Chinese, Yue

- ↑ Lau, Kam Y. [1999] (1999). Cantonese Phrase book. Lonely planet publishing. ISBN 0864426453.

- ↑ Ethnologue: "Yue Chinese", Ramsey (1987) "Yue dialects", "Yue" or older "Yüeh" in the OED, ISO code yue.

- ↑ Ramsey

- ↑ Ramsey and Ethnologue, respectively.

- ↑ Yale Romanization: Gwóngdùng wá; Jyutping: Gwong2 dung1 waa2; Mandarin: Guǎngdōng huà

- ↑ [1] - Thurgood, Graham. 2006. "Sociolinguistics and contact-induced language change: Hainan Cham, Anong, and Phan Rang Cham." Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, 17-20 January 2006, Palawan, Philippines. Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL International.

- ↑ [Lee]; Kochanski, G; Shih, C; Li, Yujia (16-20 September 2002). "Modeling Tones in Continuous Cantonese Speech". Proceedings of ICSLP2002 (Seventh International Conference on Spoken Language Processing). Retrieved on 2007-08-20.

- ↑ Cantonese speakers in the UK

- ↑ Lai, H. Mark (2004). Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions. AltaMira Press. ISBN 0759104581. need page number(s)

- ↑ Maritime Silk road. 海上丝绸之路 英 ISBN 7508509323

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||