Yellow fever

| Yellow fever Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-10 | A95. |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 060 |

| DiseasesDB | 14203 |

| MedlinePlus | 001365 |

| eMedicine | med/2432 emerg/645 |

| MeSH | D015004 |

| Yellow fever virus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

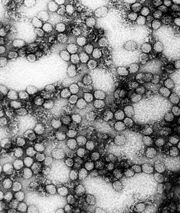

TEM micrograph: Multiple yellow fever virions (234,000x magnification).

|

||||||

| Virus classification | ||||||

|

||||||

| Type species | ||||||

| Yellow fever virus |

Yellow fever (also called yellow jack, or sometimes black vomit American Plague) is an acute viral disease.[1] It is an important cause of hemorrhagic illness in many African and South American countries despite existence of an effective vaccine. The yellow refers to the jaundice symptoms that affect some patients.[2]

Yellow fever has been a source of several devastating epidemics.[3] Yellow fever epidemics broke out in the 1700s in Italy, France, Spain, and England.[4] 300,000 people are believed to have died from yellow fever in Spain during the 19th century.[5] French soldiers were attacked by yellow fever during the 1802 Haitian Revolution; more than half of the army perished from the disease.[6] Outbreaks followed by thousands of deaths occurred periodically in other Western Hemisphere locations until research, which included human volunteers (some of whom died), led to an understanding of the method of transmission to humans (primarily by mosquitos) and development of a vaccine and other preventive efforts in the early 20th century.

Despite the costly and sacrificial breakthrough research by Cuban physician Carlos Finlay, American physician Walter Reed, and many others over 100 years ago, unvaccinated populations in many developing nations in Africa and Central/South America continue to be at risk.[7] As of 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that yellow fever causes 200,000 illnesses and 30,000 deaths every year in unvaccinated populations.[8]

Contents |

Pathogenesis

Yellow fever is caused by an arbovirus of the family Flaviviridae, a positive sense single-stranded RNA virus. Human infection begins after deposition of viral particles through the skin in infected arthropod saliva. The mosquitos involved are Aedes simpsaloni, A. africanus, and A. aegypti in Africa, the Haemagogus genus in South America,[8] and the Sabethes genus in France. Yellow fever is frequently severe but moderate cases may occur as the result of previous infection by another flavivirus. After infection the virus first replicates locally, followed by transportation to the rest of the body via the lymphatic system.[9] Following systemic lymphatic infection the virus proceeds to establish itself throughout organ systems, including the heart, kidneys, adrenal glands, and the parenchyma of the liver; high viral loads are also present in the blood.[1] Necrotic masses (Councilman bodies) appear in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes.[9],[10]

Yellow fever begins suddenly after an incubation period of three to five days in the human body. In mild cases only fever and headache may be present. The severe form of the disease commences with fever, chills, bleeding into the skin, rapid heartbeat, headache, back pains, and extreme prostration. Nausea, vomiting, and constipation are common. Jaundice usually appears on the second or third day. After the third day the symptoms recede, only to return with increased severity in the final stage, during which there is a marked tendency to hemorrhage internally; the characteristic “coffee ground” vomitus contains blood. The patient then lapses into delirium and coma, often followed by death. During epidemics the fatality rate was often as high as 85%. Although the disease still occurs, it is usually confined to sporadic outbreaks.

There is a difference between disease outbreaks in rural or forest areas and in towns. Disease outbreaks in towns and non-native people may be more serious because of higher densities of mosquito vectors and higher population densities.[11]

Prevention

In 1937, Max Theiler, working at the Rockefeller Foundation, developed a safe and highly efficacious vaccine for yellow fever that gives a ten-year or more immunity from the virus. The vaccine consists of a live, but attenuated, virus called 17D. The 17D vaccine has been used commercially since the 1950s. The mechanisms of attenuation and immunogenicity for the 17D strain are not known. However, this vaccine is very safe, with few adverse reactions having been reported and millions of doses administered, and highly effective with over 90% of vaccinees developing a measurable immune response after the first dose.

Although the vaccine is considered safe, there are risks involved. The majority of adverse reactions to the 17D vaccine result from allergic reaction to the eggs in which the vaccine is grown. Persons with a known egg allergy should discuss this with their physician prior to vaccination. In addition, there is a small risk of neurologic disease and encephalitis, particularly in individuals with compromised immune systems and very young children. The 17D vaccine is contraindicated in infants, pregnant women, and anyone with a diminished immune capacity, including those taking immunosuppressant drugs.

According to the travel clinic at the University of Utah Hospital, the vaccine presents an increased risk of adverse reaction in adults aged 60 and older, with the risk increasing again after age 65, and again after age 70. The reaction is capable of producing multiple organ failure and should be evaluated carefully by a qualified health professional before being administered to the elderly.

Finally, there is a very small risk of more severe yellow fever-like disease associated with the vaccine. This reaction occurs in 1~3 vaccinees per million doses administered. This reaction, called YEL-AVD, causes a fairly severe disease closely resembling yellow fever caused by virulent strains of the virus. The risk factor/s for YEL-AVD are not known, although it has been suggested that it may be genetic. The 2`-5` oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) component of the innate immune response has been shown to be particularly important in protection from Flavivirus infection. In at least one case of YEL-AVD, the patient was found to have an allelic mutation in a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the OAS gene.

People most at risk of contracting the virus should be vaccinated. Woodcutters working in tropical areas should be particularly targeted for vaccination. Insecticides, protective clothing, and screening of houses are helpful, but not always sufficient for mosquito control; people should always use an insecticide spray while in certain areas. In affected areas, mosquito control methods have proven effective in decreasing the number of cases.[12]

Recent studies have noted the increase in the number of areas affected by a number of mosquito-borne viral infections and have called for further research and funding for vaccines.[13],[14]

Treatment

There is no true cure for yellow fever, therefore vaccination is important. Treatment is symptomatic and supportive only. Fluid replacement, fighting hypotension and transfusion of blood derivates is generally needed only in severe cases. In cases that result in acute renal failure, dialysis may be necessary.

Current research

In the hamster model of yellow fever, early administration of the antiviral ribavirin is an effective early treatment of many pathological features of the disease.[15] Ribavirin treatment during the first five days after virus infection improved survival rates, reduced tissue damage in target organs (liver and spleen), prevented hepatocellular steatosis, and normalized alanine aminotransferase (a liver damage marker) levels. The results of this study suggest that ribavirin may be effective in the early treatment of yellow fever, and that its mechanism of action in reducing liver pathology in yellow fever virus infection may be similar to that observed with ribavirin in the treatment of hepatitis C, a virus related to yellow fever.[15] Because ribavirin had failed to improve survival in a virulent primate (rhesus) model of yellow fever infection, it had been previously discounted as a possible therapy.[16]

In 2007, the World Community Grid launched a project whereby computer modelling of the yellow fever virus (and related viruses), thousands of small molecules are screened for their potential anti-viral properties in fighting yellow fever. This is the first project to utilize computer simulations in seeking out medicines to directly attack the virus once a person is infected. This is a distributed process project similar to SETI@Home where the general public downloads the World Community Grid agent and the program (along with thousands of other users) screens thousands of molecules while their computer would be otherwise idle. If the user needs to use the computer the program sleeps. There are several different projects running, including a similar one screening for anti-AIDS drugs. The project covering yellow fever is called "Discovering Dengue Drugs – Together." The software and information about the project can be found at:

Prognosis

Historical reports have claimed a mortality rate of between 1 in 17 (5.8%) and 1 in 3 (33%). CDC has claimed that case-fatality rates from severe disease range from 15% to more than 50%.[17] The WHO factsheet on yellow fever, updated in 2001, states that 15% of patients enter a "toxic phase" and that half of that number die within ten to fourteen days, with the other half recovering.[18]

History

Yellow fever has had an important role in the history of Africa, the Americas, Europe, and the Caribbean.

Europe: 541-549

Fragile after the fall of Rome, Europe was further weakened by "Yellow Plague" (yellow fever). The Byzantine Empire suffered as well.[19]

Cuba: 1762-1763

British and American colonial troops died by the thousands in the British expedition against Cuba between 1762 and 1763. Epidemics struck coastal and island communities throughout the area during the next 140 years, with 10% of the population dying as a result.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 1793

The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793 killed as many as 2,000 people in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[20] Thousands, including President George Washington, fled the city, including most members of the Federal (Philadelphia was the capitol of the United States at this time) and city government. As a result, civil services collapsed and almost vanished. However, the mayor remained and eventually, with the help of a "Committee of Twenty" composed of volunteer residents drawn from all walks of life, order and civil services were restored.[21]

The first family of Dolley Madison, nee Dolley Payne, who would later become First Lady of the United States during James Madison's administration, were involved in this epidemic. John Todd, Dolley's husband, was a Quaker and a lawyer. He felt it was his duty to remain in Philadelphia and provide legal services (wills, probate, etc.) to those who were dying or the families of those who died. However, he moved his family across the river. One day on a visit to his family, he collapsed into his wife's arms on the doorstep of their house and died soon after. Dolley and her eldest son, John Payne Todd, contracted yellow fever but survived. Dolley's youngest son William Temple Todd and John's parents also perished in the 1793 epidemic.[21] Alexander Hamilton and his wife, Elizabeth Shuyler, contracted yellow fever but survived.

Dr. Benjamin Rush also contracted yellow fever, but survived. His fame, as a signer of the Declaration of Independence and as head medical doctor for the American army in the middle Atlantic states region during the American Revolution, brought him hundreds, perhaps thousands, of patients during this epidemic. However, his methods were severe and split the medical community at that time, resulting in an ongoing letter-writing war in the press both during and after the epidemic. Still, unlike a number of other doctors, he remained in Philadelphia and did his best to help the residents who were stuck down by the disease.[22]

Haiti: 1802

In 1802, an army of forty thousand sent by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte of France to Haiti to suppress the Haitian Revolution was decimated by an epidemic of yellow fever (including the expedition's commander and Bonaparte's brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc). Some historians believe Haiti was to be a staging point for an invasion of the United States through Louisiana (then still under French control).[23]

New Orleans, Louisiana: 1853

This outbreak claimed 7,849 residents of New Orleans. The press and the medical profession did not alert citizens of the outbreak until the middle of July, after over a thousand had already died. The reason for this silence was that the New Orleans business community feared that word of an epidemic would cause a quarantine to be placed on the city, and commerce would thus be hurt.

Norfolk, Virginia: 1855

A ship carrying persons infected with the virus arrived in Hampton Roads in southeastern Virginia in June 1855 .[17] The disease spread quickly through the community, eventually killing over 3,000 people, mostly residents of Norfolk and Portsmouth. The Howard Association, a benevolent organization, was formed to help coordinate assistance in the form of funds, supplies, and medical professionals and volunteers which poured in from many other areas, particularly the Atlantic and Gulf Coast areas of the United States. See also The Mermaids and Yellow Jack: A NorFolktale a children's historical fiction written by Norfolk author Lisa Suhay, telling of the event and founding of the Bon Secours DePaul Hospital system in the United States in response to the epidemic.[24]

Memphis, Tennessee: 1878

A devastating yellow fever epidemic occurred in 1878, with over 5,000 deaths in Memphis alone and 20,000 deaths in the whole of the Mississippi Valley. Once again, the large toll of life was due to commercial interests taking precedence over reporting the outbreak of yellow fever.[25]

Carlos Finlay and Walter Reed

Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor and scientist, first proposed proofs in 1881 that yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes rather than direct human contact.[26] Walter Reed, M.D., (1851-1902) was an American Army surgeon who led a team that confirmed Finlay's theory. This risky but fruitful research work was done with human volunteers, including some of the medical personnel, such as Clara Maass and Walter Reed Medal winner surgeon Jesse William Lazear, who allowed themselves to be deliberately infected and died of the virus.[27] Although Dr. Reed received much of the credit in history books for "beating" yellow fever, Reed himself credited Dr. Finlay with the discovery of the yellow fever vector, and thus how it might be controlled. Dr. Reed often cited Finlay's papers in his own articles and gave him credit for the discovery, even in his personal correspondence.[28] The acceptance of Finlay's work was one of the most important and far-reaching effects of the Walter Reed Commission of 1900.[29] Applying methods first suggested by Finlay, the elimination of yellow fever from Cuba was completed, as well as the completion of the Panama Canal. Lamentably, almost 20 years had passed before Reed and his Board began their efforts, twenty years during which most of the scientific community ignored Finlay's theory of mosquito transmission.

Finlay and Reed's work was put to the test for the first time in the United States when a yellow fever epidemic struck New Orleans in 1905, although efforts had been successful in Havana since 1901. A conference organized in New Orleans in 1905 by Dr. A. L. Metz resulted in President Roosevelt directing the United States' Government to take control of the matter.[30] The United States Public Health Service put into effect a mosquito control campaign,[31] this included, according to the PBS American Experience documentary The Great Fever, fumigating houses, inspecting cisterns for drinking water, and treating pools of standing water with kerosene. The result was that the death toll from the epidemic was much lower than that from previous yellow fever epidemics, and that there has not been a major outbreak of the disease in the United States since. Although no cure has yet been discovered, an effective vaccine has been developed, which can prevent and help people recover from the disease.

Use as a biological weapon

Yellow fever was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program.[32]

See also

- Tropical disease

- List of epidemics

- William C. Gorgas

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Schmaljohn AL, McClain D. (1996). "Alphaviruses (Togaviridae) and Flaviviruses (Flaviviridae)". in Baron S. Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Anker M, Schaaf D, et al (2000-01-07). "WHO Report on Global Surveillance of Epidemic-prone Infectious Diseases" (PDF) 11. WHO. Retrieved on 2007-06-11.

- ↑ Yellow Fever - LoveToKnow 1911

- ↑ TKH Virology Notes: Yellow Fever

- ↑ Tiger mosquitoes and the history of yellow fever and dengue in Spain

- ↑ Bollet, AJ (2004). Plagues and Poxes: The Impact of Human History on Epidemic Disease. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 48–9. ISBN 188879979X.

- ↑ Tomori O (2002). "Yellow fever in Africa: public health impact and prospects for control in the 21st century". Biomedica 22 (2): 178–210. PMID 12152484.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Yellow fever fact sheet". WHO—Yellow fever. Retrieved on 2006-04-18.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Quaresma JA, Barros VL, Pagliari C, Fernandes ER, Guedes F, Takakura CF, Andrade HF Jr, Vasconcelos PF, Duarte MI (2006). "Revisiting the liver in human yellow fever: virus-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes associated with TGF-beta, TNF-alpha and NK cells activity". Virology 345 (1): 22–30. doi:. PMID 16278000.

- ↑ Barnett, ED (March 2007). "Yellow fever: epidemiology and prevention". Clin Infect Dis 44 (6): 850–6. doi:.

- ↑ "Joint Statement on Mosquito Control in the United States from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency (2000-05-03). Retrieved on June 25, 2006.

- ↑ Pugachev KV, Guirakhoo F, Monath TP (2005). "New developments in flavivirus vaccines with special attention to yellow fever". Curr Opin Infect Dis 18 (5): 387–94. doi:. PMID 16148524.

- ↑ Petersen LR, Marfin AA (2005). "Shifting epidemiology of Flaviviridae". J Travel Med 12 Suppl 1: S3–11. PMID 16225801.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sbrana E, Xiao SY, Guzman H, Ye M, Travassos da Rosa AP, Tesh RB (2004). "Efficacy of post-exposure treatment of yellow fever with ribavirin in a hamster model of the disease". Am J Trop Med Hyg 71 (3): 306–12. PMID 15381811.

- ↑ Huggins JW (1989). "Prospects for treatment of viral hemorrhagic fevers with ribavirin, a broad-spectrum antiviral drug". Rev Infect Dis 11 Suppl 4: S750–61. PMID 2546248.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Mauer HB. "Mosquito control ends fatal plague of yellow fever". etext.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved on 2007-06-11, 2006. (undated newspaper clipping)

- ↑ "WHO Yellow Fever Fact Sheet". Retrieved on 2007-02-22.

- ↑ Shrewsbury, J. F. D. (1949). "The Yellow Plague". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences iv: 5. doi:.

- ↑ "Yellow Fever Attacks Philadelphia, 1793". EyeWitness to History. Retrieved on 2007-06-22.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Murphy, J. 2003. An American Plague: The True and Terrifying Story of the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793. Clarion Books. ISBN 0-395-77608-2

- ↑ Powell, J.H. 1949. Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague Of Yellow Fever In Philadelphia In 1793. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 1432576623

- ↑ Bruns, Roger (2000). Almost History: Close Calls, Plan B's, and Twists of Fate in American History. Hyperion. ISBN 0786885793.

- ↑ Suhay, Lisa. "The Mermaids and Yellow Jack. A NorFolktale.". iParenting Media Awards. Retrieved on 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Crosby, MC. 2006. The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic That Shaped Our History. Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-21202-5

- ↑ Chaves-Carballo E (2005). "Carlos Finlay and yellow fever: triumph over adversity". Mil Med 170 (10): 881–5. PMID 16435764.

- ↑ "General info on Major Walter Reed". Major Walter Reed, Medical Corps, U.S. Army. Retrieved on 2006-05-02.

- ↑ Pierce J.R., J, Writer. 2005. Yellow Jack: How Yellow Fever Ravaged America and Walter Reed Discovered its Deadly Secrets. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-47261-1

- ↑ "Phillip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection". UVA Health Sciences: Historical Collections. Retrieved on 2006-05-06.

- ↑ "Biography of METZ, Abraham L.". Retrieved on 2008-08-16.

- ↑ "Medical Timeline". Retrieved on 2008-08-06.

- ↑ "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury College, April 9, 2002, accessed November 14, 2008.

Further reading

- Downs, Wilbur H., et al.. "Virus diseases in the West Indies". Caribbean Medical Journal 1965 (XXVI(1-4)).

- Downs, Wilbur G.; Theiler, Max (1973). The Arthropod-borne Viruses of Vertebrates: An Account of the Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program, 1951-1970. Yale U.P. ISBN 0-300-01508-9.

Novels for young adults

- Anderson, L.H. 2002. Fever 1793. Aladdin Paperbacks. ISBN 0-689-84891-9 (story of a 14-year-old white girl during the 1793 Philadelphia epidemic - numerous awards)

- Stern, E.N. 2000. The French Physician's Boy: A Story of Philadelphia's 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic. Xlibris. ISBN 0-7388-5877-3 (story of a young black boy during the 1793 Philadelphia epidemic)

External links

- WHO site on yellow fever

- ECDC site on yellow fever

- Health Information for International Travel, 2005-2006:from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Symptoms of yellow fever

Historical yellow fever information

- The Great Fever on PBS

- PBS website on the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic.

- Yellow Fever in Norfolk and Portsmouth 1855 an extensive website

- Interactive Internet article on the 1855 Yellow Fever Epidemic from Pilot Online, Hampton Roads: a detailed story with maps, slides, and quiz =)

- New Orleans, 1905: Housing Conditions and the Yellow Fever: a case study

- Yellow fever deaths in New Orleans.

- Enzootic transmission of yellow fever virus in Peru.

- World Health Organization report on yellow fever

Vaccine development

- Turning Yellow - article by Christine Soares

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||