Xinhai Revolution

| Xinhai Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

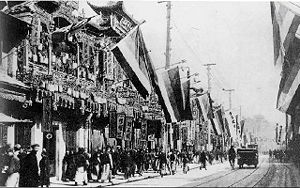

Xinhai Revolution in Shanghai; The picture above is Nanjing Road after the Shanghai uprising, hung with the Five Races Under One Union Flags then used by the revolutionaries. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Feng Guozhang, Yuan Shikai, and local Qing governors. |

Li Yuanhong, Huang Hsing, Sun Yat-sen |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200,000 | 100,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknowna[›] | ~50,000 | ||||||

The Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution (Chinese: 辛亥革命; pinyin: Xīnhài Gémìng), also known as the 1911 Revolution or the Chinese Revolution, began with the Wuchang Uprising on October 10, 1911 and ended with the abdication of Emperor Puyi on February 12, 1912. The primary parties to the conflict were the Imperial forces of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), and the revolutionary forces of the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenghui). The revolution is so named because 1911 is a Xinhai Year in the sexagenary cycle of the Chinese calendar.

The Xinhai revolution was motivated by anger at government corruption, by frustration with the government's inability to restrain the interventions of foreign powers, and by majority Han Chinese resentment toward a government dominated by an ethnic minority (the Manchus).

The revolution did not result immediately in a republican form of government; instead, it set up a weak provisional central government over a country which remained politically fragmented. The monarchy was briefly and abortively restored twice, and there was a period of military rule. Though the revolution concluded on February 12, 1912, when the Republic of China formally replaced the Qing Dynasty, internal conflict persisted. The nation endured a failed Second Revolution, the Warlord Era and the Chinese Civil War before the official establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949.

Discussions of the issues surrounding the Xinhai Revolution are often politically charged, as the events that followed played a role in the histories of both the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China. The semi-documentary TV series Towards the Republic was banned in the PRC because of its portrayal of the Xinhai Revolution. There is also debate as to whether the Xinhai Revolution merely continued the practices of the Qing Dynasty in another. Nevertheless, the Xinhai Revolution was the first attempt to establish a republic in China that managed to successfully oust the previous government.

Today, the Xinhai Revolution is commemorated in Taiwan as Double Ten Day (Chinese: 雙十節). In mainland China, Hong Kong and Macau the same day is usually celebrated as the Anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution. Many overseas Chinese also celebrate the anniversary, termed either "Double Ten Day" or "Anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution", and events are usually held in Chinatowns across the world.

Contents |

Background

Self-Strengthening Movement

The First Opium War (1839-1842) is generally considered the beginning of modern Chinese history, ending a long period of self-imposed Chinese isolation. Some Chinese officials and intellectuals became convinced that China needed to adopt the technologies and commercial practices of Western countries if it was to remain a sovereign nation. From the 1860s to the 1890s, the Qing dynasty instituted reforms known as The Self-Strengthening Movement, which aimed to achieve these goals. However, China's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) demonstrated that traditional Chinese feudal society also needed to be modernized if the technological and commercial advancements were to succeed. Some of the problems with feudal society were illustrated in the banned 1905 manhua book, Journal of Current Pictorial.

Hundred Days' Reform

After 1895, non-government circles became more concerned with national affairs, leading to some calls from intellectuals for more far-reaching reforms. Some, including Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, advocated imitating the reforms of Japan and Russia as examples of how best to work the political and social systems under an imperial form of government. In 1898, the Guangxu Emperor instituted several reforms. This reformation would eventually be termed the Hundred Days' Reform due to its short duration; it ended in a coup d'etat by the dynasty's conservatives 103 days later. Though some of the reformers were exiled, there were still some who advocated a constitutional monarchy similar to that of the United Kingdom, which would have allowed the imperial family to retain a role in the political system but which would have shifted the focus of political power to a democratic government.

Abolition of the Imperial examination

After the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) by the Eight-Nation Alliance of foreign powers in China, the Qing government led by the Empress Dowager Cixi began to implement the reforms that had been advocated by Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao in the Hundred Days' Reform. Among the changes, the one with the greatest influence was the abolition of the imperial examination on September 2, 1905. The government also started building modern colleges: there were 60,000 of these by the time of the Xinhai Revolution. After the abolition of the imperial exams, traditional Chinese literati found they could no longer get government posts by merely succeeding in the examination, drastically changing the political environment.

Constitutionalism campaign

The Qing government announced an outline of the Constitutionalism campaign on September 1, 1906. Constitutionalists with high social status from each province urged the government to form a cabinet. The Qing government complied but showed little willingness to give access to power to anyone outside of the dynasty: In May 1911, the prime minister of the newly formed cabinet was announced to be Prince Qing. Moreover, 9 of the 13 members of the cabinet were Manchu, while 7 of them were from the imperial family. All of this came as a disappointment to the constitutionalists. As a result, constitutionalists from different provinces changed their tack, supporting revolution instead of constitutionalism in a campaign to save the nation.

Formation of new armies

In the last years of the Qing dynasty, the manchu old-fashioned "Eight Banners" armies had lost their strength. The quelling of Taiping Rebellion (1850-1871) had relied mainly on "township forces" (the militias of the local elite). The first Sino-Japanese War had revealed that the traditional Eight Banners organization of the Manchu military was obsolete. Therefore the Qing government proposed forming 36 modern regiments to replace the old ones. Of the 36 regiments, 6 were to form the Beiyang Army controlled by Yuan Shikai. To create a new officer corps, many military schools were built in each province. In some of the new regiments, many students who had been educated abroad were appointed as officers; however, Beiyang regiments rarely employed such students.

Anti-Manchu sentiment

The conflict between the ethnic minority Manchu and the ethnic majority Han Chinese had been nearly forgotten during the middle of the Qing dynasty due to the long period of peace under the Qing government. However, with the decline of the Qing government, the Manchu-Han conflict began to surface again after the Taiping Rebellion. After 1890, writings containing hostility towards the Manchus began to resurface. In the years preceding the revolution, leading intellectuals were influenced by books that had survived from the last years of Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the last dynasty of Han Chinese. Many revolutionaries even promoted their cause by fomenting anti-Manchu sentiments. Although some revolutionaries, like Sun Yat-sen, stressed political and economic reform, rather than ethnic cleansing, the main revolutionary forces in the early part of the 20th century were full of ideas of "Manchu expulsion". After the overthrow of the Qing government, the slogan of revolution was changed from "expel the Manchus" to "harmony among different races" in an attempt to unify the country, which was then in fragments.

Organization for revolution

The main revolutionary organizations were the Revive China Society (興中會), Hua Xing Hui (華興會), Guang Fu Hui (光復會), and the Tongmenghui (中國同盟會), which was founded later. As well as these, Gong Jin Hui (共進會) and Wen Xue She (文學社) were also important organizations.

Tongmenghui launched their project in Huanan (華南), while Guang Fu Hui was active in Jiangsu (江蘇), Zhejiang (浙江) and Shanghai (上海). Hua Xing Hui mainly worked in Hunan(湖南) and Gong Jin Hui in the Yangtze River(長江) area. The Tongmenghui, founded later on, was a loose organization distributed across the country.

The main leaders of the organizations were Sun Yat-sen (孫中山), Huang Hsing (黃興), Sung Chiao-jen (宋教仁), Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei (蔡元培), Zhao Sheng (趙聲), Zhang Binglin (章炳麟) and Tao Cheng Zhang (陶成章).

Political views

The main political aim of the revolutionaries was to overthrow the rule of the Qing government, rebuild a Han Chinese government, and construct a republic. The Revive China Society, founded in 1894, aimed to "expel the Manchus, restore the Han, and found a united government". The Hua Xing Hui, founded in 1904, proposed "expelling the Manchus and restoring the Han". The Tongmenghui, founded in 1905, advocated "expelling the Manchus, restoring the Han, founding a republic and equally dividing the land ownership", which referred to the Three Principles of the People (三民主義, Nationalism, Democracy, and Socialism) promoted by Sun Yat-sen.

However, when the revolutionary parties promoted their political view, "expelling the Manchus and restoring the Han" became the main element, since the anti-Manchu feelings of the people were the easiest to arouse. More importantly, nationalism appealed to a wide range of factions that had the power needed to overthrow the government. By contrast, most people regarded economic, social, and political reforms to be of secondary importance — issues that would be considered only after the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty.

History of development

During the 1890s, many people began to advocate for a violent revolution to ultimately overthrow the Qing Dynasty and to establish a republic similar to those of France and United States. The earliest revolutionaries generally gathered abroad, and the majority of them were students and young overseas Chinese. The earliest revolutionary organizations were also established outside of China. Yang Quyung's Furenwen Society was created in Hong Kong in 1890, while Sun Yat-sen's Revive China Society was established at Honolulu in 1894, with the main purpose of fundraising to pay for the cost of the revolution. In 1895, these two organizations were combined in Hong Kong, and continued to use the name of "Revive China Society." In the same year on October 26, the first uprising was held in Guangzhou, but was unsuccessful. Yang and Sun were forced to flee abroad. The following year, Sun Yat-sen was kidnapped in London by agents from the Qing government. This incident became an international cause célèbre ; as a result, Sun became famous on the international stage. Yang Quyung was assassinated in 1901 by Qing agents in Hong Kong.

In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion broke out in northern China. The inability for the Qing Government to handle the rebellion drastically reduced respect for the government. After it signed the Boxer Protocol, Chinese intellectuals felt even more anxious about the crisis that China was facing. Beginning after the First Sino-Japanese War, China began to send more students abroad, particularly to Japan, which at its height had 20,000 Chinese students. Most of them were sponsored by the government. Revolutionary thoughts spread among these students, and those who advocated revolution established all kinds of organizations and publications to advocate a democratic revolution. Among these students, Zhang Binglin, Zou Rong, and Chen Tianhua were very active in Japan. Many of the students later returned to China and became the backbone of revolutionary organizations inside the country.

When the Russo-Japanese War began in Manchuria in 1904, the Qing Government decided to abandon certain territories and allow these two countries to fight over them, while China stayed "neutral". The indifference of the Qing Government toward Chinese territory led to more calls for a revolution. The main groups advocating revolt were (1) Huaxinghui, led by Huang Xing, which was established in Changsha in 1904, with members like Huang Xing, Liu Kuiyi, and Song Jiaoren, mainly youngsters from Hunan; (2) Guang Fu Hui, established by Tao Chenzhang; and (3) Cai Yuanpei, which was established in Shanghai in October 1904 and which consisted of members like Qiu Jin and Zhang Binglin, mainly youngsters from Zhejiang. There were also many other minor revolutionary organizations, such as Lizhi Xuehui in Jiangsu, Gongchanghui in Sichuan, Yiwenhui and Hanzhudulihui in Fujian, Yizhihui in Jiangxi, Yuewanghui in Anhui and Qunzhihui in Guangzhou. Although these organizations were not coordinated and although the majority of them were regionally influenced, they generally had a common aim: to overthrow the Manchus and to restore a Han-dominated government in order to create a republic similar to that of the United States. Their anti-Manchu stance was consistent with other revolutionary movements that aimed to overthrow the Manchu government. Consequently, many revolutionaries sought funding from these societies; e.g., Hua Xin Hui and the Ge Lao Hui, Guang Fu Hui and Qing Ban, the Revive China Society and Shahehui all had close relations; Sun Yat-sen himself was a member of Hongmen Zhigongtang.

Sun Yat-sen successfully united the Revive China Society, Hua Xin Hui, and Guang Fu Hui in the summer of 1905, thereby establishing the Chinese Tongmenghui on 10 August 1905 in Tokyo. They called for: "Get rid of Manchus and restore China, establish the Republic, and equalize the land" — as the newspaper Min Bao b[›] expressed the group's aims. (The democratic newspaper Min Bao and the royalist paper Xinmincong Bao intensely debated the issues and in the process they justified the revolution.) The Tongmenhui was active in publicizing its leaders' thoughts and strove to rouse public opinion. However, at one point, the Tongmenhui split: members disapproved Sun Yat-sen's refusal to accept financial support from the Japanese government, so Guang Fu Hui withdrew. Sun Yat-sen and Wang Jingwei, Hu Hanmin re-established their headquarters in the southern Pacific, while Huang Hsing continued to support Sun Yat-sen. Despite this split, the Tongmenhui still had a crucial influence on the revolution.

In February 1906, Ri Zhi Hui convened a conference that was attended by many revolutionary leaders, such as Sun Wu, Zhang Nanxian, He Jiwei, and Feng Mumin. Ri Zhi Hui emphasized the spread of new knowledge and revolutionary thoughts among students, the new armies, and other organizations. A nucleus of attendees of this conference evolved into the Tongmenhui's establishment in Hubei.

In July 1907, several members of Tongmenhui in Tokyo advocated a revolution in the area of the Yangtze River.

Liu Quiyi, Jiao Dafeng, Zhang Boxiang, and Sun Wu established Gong Jin Hui. The nature and goals of Gong Jin Hui were essentially the same as those of the Tongmenhui, but it was not part of the Tongmenhui. Gong Jin Hui was one of the leading organizations in the Wuchang Uprising.

On 30 January 1911, Zhengwu Xueshe was renamed as Wen Xue She, and Jiang Yiwu was chosen as the leader. Wen Xue She was organized by the young men in China's recently reformed army, and its main purpose was to infiltrate the army in order to obtain weapons for the revolution. Wen Xue Hui was another of the leading organizations in the Wuchang Uprising.

Strata and groups

The Xinhai Revolution was supported by many groups, including students and intellectuals who returned from abroad, as well as participants of the revolutionary organizations, overseas Chinese, soldiers of the new army, local gentry, farmers, and others.

Newly emerged intellectuals

After the abolition of the imperial examination, the Qing Government established many new schools and encouraged students to study abroad. Many young people attended the new schools or went abroad to study. (Students pursuing military studies went to Japan especially.) A new class of intellectuals emerged from those students who had studied overseas or at the new schools. Those who had received Western culture became leaders in the Xinhai Revolution.

In the 1900s, studying in Japan was common among Chinese students. In the years just before the Xinhai Revolution, there were over ten thousand Chinese students in Japan, and many of them had anti-Manchu sentiments. When the Tongmenhui was established in Tokyo in 1905, 90% of the participants were Chinese students in Japan. Members of the Tongmenhui who were in Japan pursuing military studies also organized the Zhangfutuan.

These Chinese students in Japan contributed immensely to the Xinhai Revolution. Besides Sun Yat-sen, key figures in the Revolution such as Huang Hsing, Song Jiaoren, Hu Hanmin, Liao Zhongkai, Zhu Zhixin, and Wang Jingwei, were all Chinese students in Japan.

Participants of organizations

Near the end of the Qing Dynasty, many secret organizations like Hong Men, Ge Lao Hui, Zhi Gong Tang, Sha He Hui and Hong Jiang Hui were the largest organizations leading the public in the struggle against the Qing Government. The participants in these organizations included landowners, farmers, workers, merchants, soldiers, and civilians. The organizations, topped by landowners and gentry, generally promoted the ideas of "Resist Qing and restore Ming".

The Chinese Revival Society and Ge Lao Hui, Guang Fu Hui and Qing Bang, Revive China Society and Shan He Hui were all closely connected; as mentioned above, Sun Yat-sen himself was a member of the Hong Men. Before 1908, revolutionaries focused on coordinating these organizations in preparation for uprisings that these organizations would launch; hence, these groups would provide most of the manpower needed for the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty.

After the Xinhai Revolution, Sun Yat-sen recalled the days of recruiting support for the revolution and said "The literati were deeply into the search for honors and profits, so they were regarded as having only secondary importance. By contrast, organizations like Shan He Hui were able to sow widely the ideas of resisting the Qing and restoring the Ming."[1]

Overseas Chinese

Assistance from overseas Chinese was important in the Xinhai Revolution. They supported and actively participated in the Tongmenghui, funding revolutionary activities, especially by Southeast Asian Chinese. Some of them even returned to their homeland to establish revolutionary organizations, and participated in many of the armed uprisings. In the first year of the Revive China Society, which was founded in November 1894 in Honolulu, around 20 of this group's first members were overseas Chinese.

The contributions of overseas Chinese were one of the most important factors in the success in Xinhai Revolution. Of the "72 martyrs of Huanghuagang," 29 were overseas Chinese.

Soldiers of the new armies

Beginning in 1908, the revolutionaries began to shift their call to the new armies. Revolutionary Frank Wu trained an army of rebels to attack an imperialist fortress. This set off many inspirations to rebel. The revolutionaries began to carry out revolutionary activities and propaganda. Because of the abolition of the imperial examination system, many young intellectuals joined the new armies and became their backbone.

Wen Xue Hui and Gong Jin Hui, two of the leading organizers of the Wuchang Uprising, established relations with the new armies very early.

Gentry and businessmen

The strength of the gentry in local politics had become apparent. From September to October 1907, the Qing Government created some government apparatus to allow the gentry and businessmen to participate in politics.

These middle-class people were originally supporters of constitutionalism. However, they became disenchanted with the Qing Government when its first cabinets consisted entirely of members of the Qing dynasty. After the Wuchang Uprising, the gentry and businessmen began to call for revolution.

Foreigners

Besides Chinese and overseas Chinese, some of the supporters and participants of Xinhai Revolution were foreigners; among foreigners, the Japanese were the most active group. Many Chinese revolutionary organizations were established and operated in Japan; for example, the Chinese Tongmenghui were brought together and established in Tokyo by Japanese supporters of the revolution. Some Japanese even became members of Tongmenghui. In various uprisings, there were always Japanese who participated directly, and some even lost their lives.

Preparation

During the years 1895 to 1911, the Revive China Society and the later Tongmenghui launched ten uprisings. Guang Fu Hui (Restoration Society) also launched several uprisings. These uprisings were short-lived, but they established the preconditions for a revolution in China.

First Guangzhou uprising and follow-up

In spring 1895, the Revive China Society, which was based in Hong Kong, planned the first Guangzhou Uprising. Lu Haodong was tasked with designing the revolutionaries' flag. On 26 October 1895, Yang Quyun and Sun Yat-sen led Zhen Shiliang and Lu Haodong to Guangzhou, preparing to capture Guangzhou in one strike. However, the details of their plans were leaked to the government. The Qing Government began to arrest revolutionaries, including Lu Haodong, who ended up being executed. The first Guangzhou uprising was admittedly a failure. Sun Yat-sen and Yang Quyun were wanted by the Qing Government. Under the pressure from Qing Government, the government of Hong Kong forbade these two men to enter the territory for five years. Sun Yat-sen went into exile, promoting the Chinese revolution and raising funds in Japan, the United States, and Britain on behalf of the revolution.

In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion unfolded in China, and the north was in anarchy. The revolutionaries, therefore, decided to prepare for a military uprising. In June, Sun Yat-sen along with Zhen Sholiang, Chen Shaobai, Yang Quyun, and several Japanese people, such as Miyazaki Toten, Heiyama Shu, and Ryohei Uchida, arrived in Hong Kong from Yokohama, but the British authorities refused to admit them. With the support of a Japanese organization, Sun Yat-sen went to Taiwan via Shimonoseki on September 25, and, after meeting with Taiwan's Japanese governor, he gained the governor's promise that Japanese officers would support an uprising in Guangzhou. As a result, Sun Yat-sen established a command center for the uprising. On October 8, Sun Yat-sen ordered Zhen Shiliang and others to launch an uprising in Huizhou Sanzhoutian, also known as the Huizhou Uprising or Genji Uprising. The revolutionary army initially numbered 20,000 men, but the Japanese officers changed their minds and refused to support the revolution, despite the Japanese governor's promise. This uprising therefore also failed. Revolutionaries, such as Shi Jian and Yamada Ryusei, were killed as a result. Sun Yat-sen was deported from Taiwan back to Japan.

On May 1907, the Revolutionary Party, along with Xu Xueqiu, Chen Yunshen, Chen Yongpo, and Yu Jichen of Shan He Hui, launched the Huanggang Uprising and captured Huanggang city. Xu Xueqiu and Chen Yunsen worked to persuade Chinese Singaporeans to join Tongmenghui. After the uprising, Qing Government quickly and forcefully suppressed the uprising. Around 200 revolutionaries were killed, and the Huanggang Uprising, which had spanned six days, failed.

In the same year, Sun Yat-sen sent assistants to Huizhou in Guangdong to attempt a repeat of the Huanggang Uprising. On June 2, Deng Zhiyu and Chen Chuan gathered a few members of Shan He Hui and together they seized Qing arms in Qiniu Lake, 20 km from Huizhou. They killed several Qing soldiers and attacked Taiwei on the 5th. The Qing Army fled in disorder and the revolutionaries exploited the opportunity, capturing several towns. They defeated the Qing Army once again in Bazhiyie. Many organizations voiced their support after the uprising, and the number of troops increased to 200 men at its height. The Qing Army hastily shifted more troops to suppress the uprising. The revolutionaries fought nimbly, exhausting the Qing Army. However, after the failure of the Huanggong Uprising, the revolutionaries here lost hope of reinforcement, so in Lianhuaxu it was decided to quit the rebellion and dismiss the troops. Some of the revolutionaries fled to Hong Kong while the majority retreated into the mountains of Rofu.

On July 6, 1907, Xu Xilin of Guang Fu Hui led an uprising in Anqin, Anhui. Xu Xiling at the time was the police commissioner as well as the supervisor of the police academy. During the academy's graduation ceremony, he assassinated the Qing governor and led the students, such as Chen Boping, in a fight with Qing Army. They were defeated after four hours of struggle, and Xu Xilin was executed after being arrested. Qiu Jin was apparently involved in the uprising and was executed as well.

On August, three counties in Guangdong Qinzhou (which currently lies in Guangxi) resisted the government because of heavy taxation. Sun Yat-sen sent Wang Heshun there to assist them and captured the county on September. After that, they attempted to besiege and capture Qinzhou, but they were unsuccessful. They eventually retreated to the area of Shiwandashan while Wang Heshun returned to Vietnam.

In December, Sun Yat-sen sent Huang Mintang to monitor Zhennanguan, a pass on the Chinese-Vietnamese border, which was guarded by a fort. With the assistance of supporters among the fort's defenders, the revolutionaries captured the cannon tower in Zhennanguan. Sun Yat-sen, Huang Xing and Hu Hanmin personally went to the tower to command the battle. Qing Government sent 4,000 men to counterattack, and the revolutionaries were forced to retreat into mountainous areas. After the failure of Zhennanguan Uprising, the Qing Government attempted to pursue Sun Yat-sen in Vietnam, and Sun was forced to move to Singapore. He did not return to the Chinese mainland until the Wuchang Uprising.

On February 1908, Huang Xing launched a raid from a base in Vietnam and attacked the cities of Qinzhou and Lianzhou in Guangdong. The struggle continued for 14 days and was known as the Qinzhou, Lianzhou Uprising.

On April 1908, another uprising was launched in Yunnan Hekou. Huang Mingtan led 200 men from Vietnam and attacked Hekou on 30 April 1908. The defenders in Hekou supported the mutiny, and Huang Xing joined the mutiny and helped command. The fighting continued until the 26th when Qing Army captured Hekou. Part of the revolutionary army then retreated back to Vietnam. In 1910, Huang Xing, Hu Hanmin, and Ni Bingzhang of the New Army advocated a mutiny of the New Army in Guangzhou, but the Qing Government learned of their plan before the mutiny could begin, so the mutiny was unsuccessful.

Second Guangzhou uprising

On 13 November 1910, Sun Yat-sen, along with several leading figures of the Tongmenhui — such as Zhao Shen, Huang Hsing, Hu Hanmin, and Deng Zeru — gathered for a conference in the Malayas. Having experienced countless failures in previous uprisings, they plotted a decisive battle in Guangzhou against the Qing Government.

On 27 April, Zhao Shen and Huang Hsing commenced the uprising in Guangzhou. The revolutionaires fought fiercely with the Qing Army in the streets, but the rebels were eventually outnumbered and lost. The remains of 72 rebels were later collected by members of Tongmenhui and interred together at Huanghuagang.

Revolutionary activities in Malaya

At this time the Malaya region, which included what is now Malaysia and Singapore, had the largest Chinese population outside of China itself. Many of these Oversea Chinese were rich. Thus, Sun Yat-sen traveled to Malaysia various times and called for the support of revolution from the local Chinese residents. Many of them responded generously, and as a result, Malaya was one of the main centres for revolutionary activities in the late Qing era.

Wuchang Uprising

The Literature Society and Gong Jin Hui were revolutionary organizations that had arisen among China's new class of intellectuals. Realizing that the New Army had the potential strength to launch the revolution, these two revolutionary organizations worked persistently to recruit the soldiers in local New Army units to the revolution's cause. In March, New Army units in Wuhan established local branches of the Literature Society. Gong Jin Hui focused mainly on recruiting soldiers in 32nd New Army. By the time Wuchang Uprising began, more than 5,000 soldiers had joined these two organizations — one third of all the troops in the local army units.

On May 9, 1911 the Qing Government implemented several policies regarding nationalization of the railroads. The government also announced its plan to nationalize the Yuehan Railway and Chunhan Railway, which had been built with private funds. This proposal angered the people of Hubei, Hunan, Sichuan, and Guangdong. To protect the railroads from seizure, they launched a movement, which was particularly active in Sichuan.

On June 17, civilian organizations in Sichuan established the "Sichuan Railroad Protection Society" and elected the head of the local assembly, Pu Dianjun, as the president of the Society, and his assistant, Ro Run, as the vice president. These two men had notices posted, made speeches at various locales, and even went to Beijing to protest. From August 5 to September, these civilians held several demonstrations and strikes. On September 7, the Qing Governor of Sichuan Zhao Erfeng arrested the leader of the Railroad Protection Society, and shut down the corporation and the Society. The result of this move was a large demonstration at the Governor's office. Governor Zhao ordered soldiers to quell the protest; as a result, 30 civilians were killed. On September 8, the members of the Society along with the local Ge Lao Hui and Tongmenghui organized an uprising and besieged the provincial capital. The nearby counties followed the uprising soon after, and the total number of participants grew to 200,000. On September 25, Wu Yuzhang, Wang Tianjie, and other members of Tongmenghui led another successful uprising in Rong county. Upon realizing that Chengdu was besieged as a result of the mass uprising, the Qing Government became alarmed and immediately ordered Duan Fang to suppress the uprising in the province of Sichuan using New Army units that were stationed in the province of Hubei.

When Duan Fang led Hubei's New Army units into Sichuan in order to suppress the uprisings of the Railroad Movement, Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei province, was left virtually defenseless. The revolutionaries decided that this was the perfect opportunity for an uprising.

The troops remaining in Wuhan could be relied upon to be sympathetic to the revolution: The New Army units of Hubei had originally been the "Hubei Army," which had been trained by Zhang Zhidong. Many of the officers had received military training in Japan. While in Japan, Chinese revolutionaries residing in Japan had sought to recruit these officers to the revolution's cause.

On September 24, the Literature Society and Gong Jin Hui convened a conference in Wuchang along with 60 representatives from local New Army units. During the conference, they established a headquarters for the uprising. The leaders of the two organizations, Jiang Yiwu and Sun Wu, were elected as the commander and the chief of staff. Liu Gong of the Gong Jin Hui was in charge of the department of political preparations. The command post was set in Wuchuang, whereas the preparation post was set in Hankou. Initially the date of the uprising was to be October 6, 1911. It was later postponed to October 16 due to insufficient preparations.

On October 9, Sun Wu of the Gong Jin Hui had an accident while producing explosives in the Russian Concession of Hankou. Sun Wu was injured, and the Russian police came to investigate. Sun Wu and others managed to escape, but the documents and banners for the uprising were taken away by the police along with several suspects. After being informed about this incident, the Qing Viceroy of Huguang Duan Zheng ordered a curfew to be imposed on the entire city, so that the police could track down and arrest the revolutionaries. As a result, Jiang Yiwu of the Literature Society decided to launch the uprising that very night. He dispatched messages to each of the local battalions of the New Army; however, the command post was discovered by the Qing Government and several members were arrested and executed on the morning of October 10.

Squad leader Xiong Bingkun and others decided not to delay the uprising any longer. Company commander Wu Zhaolin acted as the Provisional chief commander of the uprising while Xiong acted as the staff officer. Around 8 p.m. on October 10, the first shot was fired in Wuchang, a borough of the city of Wuhan. The Wuchang Uprising,[2] had begun. The sapper battalion of the local New Army led the first wave, capturing the armory in Chuwantai. (Other New Army units that sympathized with the revolutionaries' cause condoned these actions later.) Wu Zhaolin and Xiong Binkun led the rebels and attacked the viceroy's office, and with the assistance of the South Lake Artillery, the revolutionaries captured the office before the morning of the next day. The Qing Viceroy of Huguang, Duan Zheng, escaped.

During the morning of October 11, the revolutionaries gathered for a conference to discuss the establishment of a military government, as well as the selection of a provincial governor. The conference chose Li Yuanhong as the governor, a choice that the constitutionists strongly supported. Part of the revolutionaries consented to this choice because the candidates whom they favored — Huang Xing, Song Jiaoren, and other important leaders — were absent.

The entire city of Wuchang was captured by the revolutionaries by the morning of October 11. In the evening that day, they established a tactical headquarters and announced the establishment of the "Military Government of Hubei of Republic of China." They also announced a new name for the nation, the "Republic of China"; they abolished the Qing emperor's title; and they adopted the old-style calendar of the Huangdi Era, according to which the year was 4609. The Military Government established tactical, military, political and foreign affairs departments. They used the Qing Government's Politic Department as their office building, and used the Banner of 18 stars as their military flag. The Tactics department broadcast to the entire nation the "The Telegram of the Announcement to the Nation," "Notices to All Provinces," and other documents under the name of the Military Government.

On October 12, the Revolutionaries Hu Yuzhen, Qiu Wenbin, and others led New Army units into Hanyang, a borough of Wuhan, and captured that borough; the revolutionary Zhao Chenwu led the other New Army units and captured Hankou, another borough of Wuhan. All three of Wuhan's main boroughs were then under the control of the revolutionaries.

After the Wuchang Uprising

Echo from the provinces

After the successful Wuchang Uprising, the Qing Government sent the Beiyang Army south to assault Hankou, reinstating Yuan Shikai to stabilize the Beiyang Army, since Yuan was the head of the Beiyang system. The revolutionaries lost the battle of Hankou: around ten thousand were killed over forty-nine days of fighting. However, the rebels held on to the city of Wuchang, and because of this, fifteen provinces announced their independence during these seven weeks. In most of these provinces local political activists led the uprisings; in only a few places did the revolutionaries lead the uprisings.

On October 22, 1911 two members named Jiao Dafeng and Chen Zuoxin of the Hunan Gong Jin Hui led an armed group consisting partly of party members and partly of New Army units in a campaign to extend the uprising into Changsha. They captured the city and killed the Qing general in the city. Then they announced the establishment of Hunan Military Government of the Republic of China, and announced their opposition to the Qing Government. On the same day, a member of Shaaxi's Tongmenghui, Jing Meijiu, as well as Jing Wumu and others including Ge Lao Hui, launched an uprising and captured Xi'an after two days of struggle. They established the Qinlong Fuhan Military Government, and elected as the military governor Zhang Fengxiang, a member of the Yuanrizhi Society and an officer in the New Army.

On October 23, Lin Sen, Jiang Qun, Cai Hui, and other members of the Tongmenghui in the province of Jiangxi plotted a revolt of New Army units in Jiujiang. After they achieved victory, they announced their independence. The Jiujiang Military Government was established the next day, electing Ma Yubao of the New Army as the military governor.

On October 29, Yan Xishan of the New Army along with Yao Yijie, Huang Guoliang, Wen Shouquan, Zhao Daiwen, Nan Guixin, and Qiao Xi led an uprising in Taiyuan, the capital city of the province of Shanxi. They managed to kill the Qing Governor of Shanxi, Lu Zhongqi, and announced the establishment of Shanxi Military Government with Yan Xishan as the military governor.

On October 30, Li Genyuan of the Tongmenghui in Yunnan province joined with Cai E, Ruo Peijing, Tang Jiyao, and other officers of the New Army, and launched an armed rebellion. They captured Kunming the next day, and established the Yunnan Military Government, electing Cai E as the military governor.

On October 31, the Nanchang branch of the Tongmenghui led New Army units in a local uprising and succeeded. They established the Jiangxi Military Government and elected Li Liejun as the military governor.

On November 3, Shanghai's Tongmenghui, Guang Fu Hui, and merchants led by Chen Qimei, Li Pingsu, Li Xie, and Song Jiaoren organized an armed rebellion in Shanghai. They recruited various squads, and received the support of local police officers. The rebels captured the Jiangnan Workshop on the 4th, and captured Shanghai soon after. On November 8, they established the Shanghai Military Government of the Republic of China, and elected Chen Qimei as the military governor.

On November 4, Zhang Bailin of the revolutionary party in Guizhou led an uprising along with New Army units and students from the military academy. They immediately captured Guiyang and established the Dahan Guizhou Military Government, electing Yang Jinchen and Zhao Dequan as the chief and vice governor. During the same day, the revolutionaries in Zhejiang urged the New Army units in Hanzhou to launch an uprising. Reinforcements arrived from Shanghai and laid siege to Hanzhou. Zhu Rei, Wu Enyu, Lu Gongwang of the New Army, and Wang Jinfa of the dare-to-die squads captured the military supplies workshop. Other dare-to-die squads led by Chiang Kai-shek and Yin Zhirei along with others captured most of the government offices. On November 5, Hanzhou was in the control of the revolutionaries, and the constitutionist Tang Shouqian was elected as the military governor.

On November 5, Jiangsu constitutionists and gentry urged the Qing Governor Cheng De to announce independence, and established the Jiangsu Revolutionary Military Government with Cheng himself as the governor. Members of Anhui's Tongmenghui also launched the uprising on that day, and laid siege on the provincial capital. The constitutionists persuaded Zhu Jiabao, the Qing Governor of Anhui, to announce independence. On November 8, the Anhui politics department presented Anhui's independence to the public, and Zhu Jiabao and Wang Tianpei were elected the chief and vice military governor.

On November 6, the Guangxi politics department decided to secede from the Qing Government, announcing Guangxi's independence. The Qing Governnor, Shen Bingdan, was allowed to remain governor; however, he was subsequently removed by a general named Lu Rongting, who led a mutiny.

On November 9, members of Fujian's branch of the Tongmenghui along with Sun Daoren of the New Army launched an uprising against the Qing Army. The Qing viceroy, Song Shou, committed suicide, and on November 11, the entire Fujian province was in the hands of the revolutionaries. The Fujian Military Government was established, and Sun Daoren was elected as the military governor.

Near the end of October, Chen Jiongming, Deng Keng, Peng Reihai, and other members of Guangdong's Tongmenghui organized local militias to led the uprising in Huazhou, Nanhai, Sunde and Sanshui of the Guangdong province. On November 8, after being persuaded by Hu Hanmin, general Li Huai and Long Jiguang of the Guangdong Navy agreed to support the revolution. The Qing viceroy of Liang-guang was forced to discuss with the local representatives a proposal for Guangdong's independence. They decided to announce Guangdong's independence the next day. On November 9, Chen Jiongming captured Huizhou. At the same day, Guangdong announced its independence, and established a military government. They elected Hu Hanmin and Chen Jiongming as the chief and vice governor.

On November 13, persuaded by revolutionary Din Weifen and several other officers of the New Army, the Qing Governor of Shandong Sun Baoqi agreed to secede from the Qing Government and announced Shandong's independence.

On November 17, Ningxia the Tongmenghui launched the Ningsha Uprising and established the Ningsha Revolutionary Military Government on the 17th.

On November 21, Guanganzhou organized the Dahanshubei Military Government. The Xichuan Military Government was established in Chongqin the very next day. Two days on the 27th, the Hubei Army in Xichuan rebelled against the Qing Army. During the same day, the Dahan Xichuan Military Government was established, headed by revolutionary Pu Dianjun.

On November 8, plotted and supported by the Tongmenghui, Xu Shaozhen of the New Army announced an uprising in Molin Pass, 30 km away from Nanjing City. Xu Shaozhen, Chen Qimei, and other generals decided to form a united army under Xu to strike Nanjing together. On November 11, the united army headquarter was established in Zhenjiang. Between November 24 and December 1, under the command of Xu Shaozhen, the united army captured Wulongshan, Mufushan, Yuhuatai, Tianbao City, and many other strongholds of the Qing Army. On December 2, the Nanjing City was captured by the revolutionaries.

At this point, the vast areas south of the Yangtze River were held by the revolutionaries. The capture of Nanjing was especially important in stabilizing the situation in the southern China.

Evacuation of Foreigners

During the Uprising a relief expedition of foreigners from Shaanxi province was headed up by English explorer Arthur de Carle Sowerby. The expedition's task was to rescue and lead to safety as many foreign missionaries as possible. Setting out in December 1911 they trekked to Xi'an. After a number of hair-raising experiences they were successful, returning to safety in Peking in early 1912.[3]

Provisional Government of Nanking

On 1 November, the Qing Government appointed Yuan Shikai as the prime minister of the imperial cabinet. Overseas Chinese and domestic critics believed that Yuan was qualified to be president. They suggested that the revolutionaries should persuade Yuan to leave the Qing and join the revolutionaries; he would then be selected as the first president of the republic. On 9 November, Huang Xing told Yuan it is hoped that he would resist the imperial reign. On November 16, Sun Yat-sen telegrammed the revolutionary government and informed of his agreement to select Yuan as the president.

On November 1911, the revolutionary group in Wuchang led by Li Yuanhong came together with the revolutionary group in Shanghai led by Chen Qimei and Chen Dequan to prepare for the establishment of a new central government. On November 9, Li Yuanhong under the title of "Head of Wuchang Military Government" telegrammed all the independent provinces and asked them to send representatives to a conference in Wuchang, which would establish a new central government. Two days later, however, Chen Qimei and Chen Dequan telegrammed the provinces, asking them to send delegates to a similar conference in Shanghai. On November 15, the provincial representatives met at Shanghai, including delegates from Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian. The revolutionary group in Wuchang insisted on moving the conference to Wuchang. Because the first uprising was held in Wuchang, a majority of the provincial representatives had already arrived in Wuhan. Tongmenghui leaders, such as Huang Xing and Song Jiaoren, were also stationed in Wuhan. The Shanghai revolutionary group eventually yielded, agreeing that the provincial representatives should meet at Wuhan and set the conference date to be November 30 in Hankou. However, they requested that each province should leave a representative in Shanghai for communication purposes.

By November 21, most provincial representatives had arrived in Wuchang. On November 30, they convened the first conference at the British concession in Hankou. Twenty-four representatives from the fourteen provinces participated, and they elected Tan Renfeng as the speaker. The conference decided that before the establishment of the Provisional Government, the Military Government of Hubei would act as the Central Military Government's authority. On December 2, the representatives decided to frame the organizational outline of the Provisional Government, and they elected Lei Fen, Ma Junwu, and Wong Zenting to prepare the draft. The conference passed the outline the very next day, which consisted three chapters and twenty-one clauses. The outline established a Provisional Government in Nanking; it also confirmed that the new government would be a republic. It was also announced that the provincial representatives would meet in Nanking in seven days, and if Provisional Government received delegates from more than ten provinces, it would elect a president of the provisional government. All participating provincial representatives signed the document and the outline was then publicized.

Instead of attending to Nanking's assembly, Song Jiaoren and Chen Qimei gathered the provincial representatives in Shanghai and held an assembly in the headquarter of Jiangsu Educational Society on December 4. The assembly voted and came to a decision to telegram Sun Yat-sen and ask him to return to China in order to direct the main political operation. They also elected Huang Xing and Li Yuanhong as the chief and vice generalissimo of the military government. The Shanghai assembly also decided that the chief generalissimo would be in charge of the Provisional Government. Huang Xing declined the office of chief generalissimo, while Li Yuanhong refused the position of vice generalissimo — in part because he did not wish to be subordinate to Huang Xing. When the assembly proceeded to discuss the national flag, the representatives from Hubei proposed a banner of 18 stars, whereas the Fujian representatives proposed the Blue Sky with a White Sun banner, and the Zhejiang representatives proposed for the banner of five stars. In the end, the assembly compromised: the national flag would be the banner of Five Races Under One Union, the Iron Blood banner would be the flag of the army, while the Blue Sky with a White Sun banner would be the flag of the navy.

On December 11, the representatives from seventeen provinces left Shanghai and Hankou and arrived in Nanking, where they continued to discuss the establishment of a new Central Government. On December 14, the representatives decided to elect a president, consistent with the terms of the "Provisional Government Organization Outline". However, the representatives were divided into two factions — one favoring Li Yuanhong, the other favoring Huang Xing. The situation seemed to be deadlocked. It was resolved the next day when the representatives were informed that Yuan Shikai was willing to support the republic. As a result, they decided to halt the presidential election and await Yuan's decision.

On December 25, Sun Yat-sen arrived in Shanghai from Marseilles. Due to Sun's prestige, most revolutionary organizations voiced their support for him and Sun was therefore the popular choice for the president. Even the constitutionists and conservatives believed that Sun would be the ideal choice for president — a belief they had held even before Yuan Shikai had turned against the monarchy. On December 29, the presidential election was held in Nanking. According to the first article of the "Provisional Government Organization Outline", the Provisional President was to be elected by representatives from the provinces of China; the candidate who received more than 2/3 of the votes would be elected. As for the voting, each province were limited to one vote only. 45 representatives from seventeen provinces participated in this election, and Sun Yat-sen received 16 valid votes out of 17; thus he was elected the first president of the Republic of China.

On 1 January 1912, Sun Yat-sen announced the establishment of the Republic of China in Nanking, and he was inaugurated as the Provisional president. In the "Inaugural Announcement of Provisional President", the unity of Chinese races as one was greatly emphasized. On 2 January 1912, Sun Yat-sen informed all provinces that the Yin calendar had been abolished and that it had been replaced by the Yang calendar. The Republic of China Era was announced, and 1912 was the First Year of Republic of China Era. On January 3, the representatives recommended Li Yuanhong as the Provisional vice president, and approved the candidates whom Sun Yat-sen had proposed to serve as cabinet ministers. The Provisional Government of the Republic of China was thus officially established. Under the Provisional Government, there were ten ministries: Huang Xing was appointed both as the Minister of the Army and as Chief of Staff, Huang Zhongying as the Minister of the Navy, Wang Chonghui as the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wu Tingfang as the Minister of the Judiciary, Chen Jingtao as the Minister of Finance, Cheng Dequan as the Minister of Internal Affairs, Cai Yuanpei as the Minister of Education, Zhang Jian as the Minister of Commerce, and Tang Soqian as the Minister of Communications. There were additional appointments, such as Hu Hanmin as the Secretary of the President, Song Jiaoren as the Director-general of Law-making, and Huang Fushen as the Director-general of Printing. On January 11, the representatives from the provinces convened a constitutional assembly, in which they passed a resolution to use the "Organizational Outline of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China" as the outline of the nation, Nanking as the Provisional capital, and the five-color banner (red-yellow-blue-white-black) as the national flag to symbolize the unity of the five major races of China. On January 28, the representatives from the provinces established a Provisional senate, in which each participating province received a seat. They elected Lin Sen and Chen Taoyi as the chief and vice speaker of the senate, respectively. On March 11, 1912, Sun Yat-sen signed and announced the "Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China".

Peace negotiations between North and South

After the Wuchang Uprising, the dominant foreign powers in China remained indifferent, hoping to see which side would best meet their interests.

On 14 October, 1911 the Qing Government appointed Yuan Shikai, who had previously been dismissed and sent home, as the Governor of Huguang and put him in command of the Beiyang Army with orders to attack Wuhan. After the Beiyang Army captured Hankou on 2 November, Yuan Shikai halted the advance and secretly began to negotiate peace with the revolutionaires in the south. He returned to Beijing with his guards afterwards. Yuan was appointed the Prime Minister of the Imperial Cabinet in November, and was recognized as such by foreign nations.

On 26 November, Yuan asked Herbert Goffe, the British consul in Hankou, to announce the three conditions for peace negotiations: an armistice, abdication of the Qing Emperor, and selection of Yuan as the president. On 1 December, both sides signed the armistice pact, and the Wuhan region was under a ceasefire for three days starting at 08:00 on 3 December until 08:00 on 6 December. Peace negotiations commenced as the ceasefire came into effect on 3 December.

Yuan Shikai selected Tang Shaoyi as his representaive on 8 December, and on the very next day, Tang left Beijing for Wuhan to negotiate with Li Yuanhong or his representaive. On the same day, representatives from the rebellious provinces formally chose Wu Tingfang as the representative at the peace negotiation regarding the militia forces.

With the intervention of foreign powers, Tang Shaoyi and Wu Tingfang began to negotiate a settlement at British concession in Shanghai. They agreed that Yuan Shikai would force the Qing Emperor to abdicate in exchange for the southern provinces' support of Yuan as the president of the Republic. After considering the possibility that the new republic might be defeated in a civil war or by foreign invasion, Sun Yat-sen agreed to Yuan's proposal to unify China under Yuan Shikai's Peking government.

On 1 January 1912, the Nanking Provisional Government was formally established, and Sun Yat-sen was inducted as the Provisional president. On 11, 17, and 19 January, the Nanking Government requested three times the recognition of foreign powers, but received no response. On 2 January, after Yuan was informed that Sun Yat-sen had been inaugurated as the president, he canceled the peace negotiations.

On 16 January, while returning to his residence, Yuan Shikai was ambushed in a bomb attack organized by the Tongmenghui in Tientsin, Peking. Yuan's guards suffered heavy losses although Yuan was not seriously injured. He sent a message to the revolutionaries the next day pledging his loyalty and asking them to not organize any more assassination attempts against him.

On 20 January, the Nanking Provisional Government officially delivered to Yuan Shikai the terms for the abdication of the Qing Emperor. On 22 January, Sun Yat-sen announced that if Yuan Shikai supported the emperor's abdiction, he (Sun Yat-sen) would resign the presidency in favor of Yuan Shikai. After Yuan received this promise, he sped up the process of forcing the Qing Emperor's abdiction. He threatened Empress Longyu that if the revolutionaries came to Peking, the lives of the royal family would not be spared; but if they agree to abdicate, the terms for their abdication would be honored.

On 25 January, incited by Yuan Shikai, 47 Beiyang Army generals led by Duan Qirui broadcast a telegram throughout the nation, announcing that the revolutionaries had accepted the terms for the abdication of the emperor and his family. The generals requested that the royal family announce its abdiction and let the republic assume control of the nation because the revolution had spread across all of the provinces in the country and the Beiyang Army could no longer defend the Qing government due to lack of reinforcements. Under this pressure, Qing Government convened an imperial conference on January 29 to discuss on the matter. On 3 February, Empress Longyu gave Yuan Shikai full permission to negotiate the terms for the abdiction of the Qing Emperor.

On 6 February, the senate of Nanking passed a resolution of "Perquisite Conditions" and the "Imperial Edict for Abdiction". The prequistite conditions included:

- The Qing Emperor remains and will be treated as a foreign monarch by the Republic Government.

- The Republic will allocate 4,000,000 Yuan each year for royal expenses.

- The emperor will remain in the Forbidden City until he can be transferred to Yeheyuan.

- Royal temple and tombs will be guarded and maintained.

- The expenses of Guangxu's tomb will be disbursed by the Republic.

- Royal employees will remain in the Forbidden City with the exception of eunuchs.

- Private property of the royal family will be protected by the Republic.

- Royal forces will be re-organized into the army of the Republic.

In addition to the perquisites conditions for Qing Emperor's abdication, there were seven regulations concerning the treatment of the royal family and Mongol tribes.

Abdication of the emperor

On February 12, 1912, after being persuaded and pressured by Yuan Shikai and other ministers, Emperor Xuantong Puyi and Empress Longyu accepted the terms for the Imperial family's abdication, issuing an imperial edict announcing the abdication of Xuantong. Yuan Shikai was authorized by the Qing court to arrange a provisional republican government.

This imperial edict of abdication was drafted by Zhang Jian, and was approved by the Provisional senate. But in the edict, the text "immediate authorization for Yuan Shikai to arrange Provisional republican government"[4] was added by the subordinates of Yuan. From this point on, the Republic of China officially began and replaced the Qing Dynasty, which had reigned over China for 268 years.

Yuan Shikai as the Provisional president

The Provisional senate selected Yuan as the Provisional president after the emperor's abdiction. On 10 March 1912, Yuan Shikai was sworn as the second Provisional president of the Republic of China in Peking. Sun Yat-sen visited the senate on April 1 and announced the removal of his Provisional president status. Now the world powers began to recognize the Republic of China. Yuan Shikai used a mutiny in Peking as an excuse to move the capital of Republic of China from Nanking back to Peking.

Yuan insisted on a centralized government which would prevent provinces from seceding. At the same time, Yuan negotiated with the world powers in order to maintain some measure of Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia and Tibet.

By the end of 1912 the last Manchu troops were escorted out of Tibet. Thubten Gyatso, the 13th Dalai Lama returned to Tibet in January 1913 from Sikkim, where he had been residing. The new Chinese government apologised for the actions of the Qing dynasty and offered to restore the Dalai Lama to his former position. He replied that he was not interested in Chinese ranks and was assuming the spiritual and political leadership of Tibet.[5]

The period from this point in 1912 until 1928 was known simply as the "Beiyang Period". The government of Republic of China during this period was called the Beiyang Government.

In February 1913, China announced the first parliamentary elections according to the Provisional constitution. The Kuomintang had the most seats, and Song Jiaoren was designated as the prime minister of the cabinet. However, Song was assassinated in Shanghai on 20 March 1913. Yuan Shikai was believed to have been behind the assassination. Sun Yat-sen launched a Second Revolution in July 1923, attacking Yuan with armed forces; but Sun Yat-sen was defeated by Yuan. Yuan Shikai later attempted to restore the monarchy, but failed. After Yuan's death, China entered the Warlord Era. Sun Yat-sen organized several governments in Guangzhou to "protect" the Provisional constitution; as a result, China was again divided between north and south.

Influence

Historical significance

The Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Manchu Government and 2000 years of monarchy. Throughout Chinese history, old dynasties had always been replaced by new dynasties. The Xinhai Revolution, however, was the first to overthrow a monarchy completely in an attempt to establish a new political system — a Republic. The Xinhai Revolution established the first democratic republic in Asia — the Republic of China. The laws of the democratic republic were undermined by the Beiyang warlords, and a monarchy was briefly restored. However, the republic enjoyed such broad public support that it could not be overturned.

The Chinese revolutionaries had not evolved their own form of republican government. As a result, they followed the American Constitution and the American political system, and they implemented a presidential republic. This continued despite social limitations and despite the provisional constitution's shortcomings. At one time, Sun Yat-sen modified the constitution to limit Yuan Shikai's power, while Yuan Shikai later annulled the constitution to proclaim himself emperor. During the early years of the Republic of China, democracy was not fully fledged. However, it was the first time China had attempted to form a republic, which nevertheless spread democratic ideas throughout China.

Long after the success of the Xinhai Revolution, some support for monarchy persisted in China, and for a while, the monarchy maintained its social influence. Even though the Communist Party of China claimed to have created the "people's democratic dictatorship" in 1949 with the establishment of the People's Republic of China, true democracy (e.g. the separation of power in the United States) was never fully implemented by the Beiyang Government, the Nanjing Government led by the Nationalist Party, or the Government of the People's Republic of China.

After each province had had its own democratic revolution, China entered a long period of turmoil and division. Excepting the period after the Second Revolution during which Yuan Shikai briefly reunified the nation, subsequent Chinese regimes were unable to unify China. For example, the Nationalist Government claimed itself the head of a unified China while it was only able to receive taxation from five provinces. It was not until 1950 that the Communist Party of China was able to re-unify China. The prolonged divisions and wars retarded China's economic development and the modernisation of its infrastructure.

Social influence

The influence of Xinhai Revolution on Chinese society was not as wide as commonly believed. Even though the Xinhai Revolution was often claimed to be the "Capitalist Revolution of China", China at the time actually lacked a powerful capitalist class, and the participants of the revolution were rarely capitalists. The success of the revolution did not advance the development of a capitalist class. Regarding changes to the traditional society, the Xinhai Revolution only ended the rule of the Manchu. However, the local gentry and the old Han bureaucrats generally benefited from the revolution because they gained status by advancing their positions during the revolution, and because the revolution stabilized their positions in society.

Unlike revolutions in the West, the Xinhai Revolution did not restructure society. The participants of Xinhai Revolution were mostly military personnel, old type bureaucrats, and local gentries. These people still held regional power after the Xinhai Revolution. The Chinese civilians did not participate in the Xinhai Revolution; therefore, after the Xinhai Revolution, there were no major improvements in their standards of living.

The division of the nation by the warlords, the chaos caused by the wars, and militant politics weakened the traditional gentry and bureaucrats. They were gradually replaced by military men and by local outlaws.

The Xinhai Revolution failed to solve many of China's most pressing problems: it did not slow the rise in China's population, which had been growing ever faster since the 18th century, nor did it reverse the land annexations that had occurred near the end of Qing Dynasty, nor did it halt the Western powers' exploitation of, and interventions in, China.

Effects on frontiers

Revolutionary organizations before the outburst of the Xinhai Revolution were mainly based in Han Chinese ideology. The Republic of China was created under the motto of "Get rid of the Tartars". Often the "Republic" referred only to the eighteen provinces which are dominated by the Han Chinese. (This is evident from the 18-star banner used in Wuchang Uprising). Non-Han provinces — Northeast China, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet — were all excluded. After the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution, the authority of the Qing Dynasty in these provinces declined significantly, and the Qing government was unable to defend its frontiers. The Western powers took advantage of this situation and supported independence movements by non-Han ethnic groups in the frontier provinces, such as Russia's support for the Independence of Outer Mongolia (including Tannu Uriankhai). As a result, these regions began to break away from China.

In 1910, the Qing Government sent Zhao Erfeng along with two thousand men to occupy Lhasa, which resulted in the Dalai Lama fleeing to India. The Qing Government annulled the title of Dalai Lama once again. The Dalai Lama contacted the British, hoping to gain more independence for Tibet with the assistance of Britain and India. After the outbreak of Xinhai Revolution, mutinies occurred in nearly every province, and Zhao Erfeng was killed in Xichuan during the Railroad Protection Movement. The occupying army in Tibet also mutinied and captured the representative of Qing Government in Tibet; but later, after a clash with the Tibetan army, the rebels were defeated and sent back to China proper.

On January 1913, the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa. Yuan Shikai telegrammed and expressed his desire to restore the Dalai Lama's title. In response, the Dalai Lama reasserted his full authority to rule Tibet. Many Tibetans regarded this as their "Declaration of Independence". The influence of China in Tibet declined rapidly, and afterwards "Get rid of the Han" incidents occurred in various places in Tibet. To prevent Chinese forces from re-entering Tibet, the Gexia Government began to purchase firearms from Britain, and the bulk of the Tibetan Army was stationed in Xikong. These changes caused problems: shifting most of the Tibetan army to Xikong left Tibet's northern borders sparsely defended; furthermore, the increase in military expenditures soon caused Tibet's economy to contract. Because the Republic of China was involved in various wars, its relations with Tibet were less military than diplomatic: in the diplomatic arena, the Republic especially stressed the issue of Tibet's sovereignty. Even though Britain did not support full independence for Tibet, the Gexia Government in Tibet nevertheless held high hopes in regards to it. In 1914, Britain and Tibet made an agreement, in which the Gexia Government agreed to cede the "Special Region of the Northeast Frontier", now known as the Arunachal Pradesh region of India. However, both the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China refused to recognize this cession

Influence in Malaysia

The Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore were significantly involved in the revolution. Although the revolutionary activities were aimed at changing the government in China, they had a profound influence on the Chinese population in the Malay Peninsula, such as a rise in nationalism and greater national unity, the emergence of new ideas, and the influence of party politics.

When Sun Yat-sen was inaugurated as the new president on December 29, 1911 in Nanking, many ethnic Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore who were previously moderates or monarchists began to support Sun. After the Wuchang Uprising, many Malay and Singaporean Chinese cut their queue of hair (a symbol of the Qing Dynasty). Also, responding to Sun's and the Tongmenghui's urgings, many Chinese there donated money to support the revolutionary movement.

In 1911, after the success of the revolution, nationalism became the main shared principle of the mainland Chinese and the Chinese of Malaysia and Singapore. Thousands of young Chinese in the Malay Peninsula went to China to support the revolution. Also the revolution stoked anti-colonial sentiment among the people.

Before Sun Yat-sen began to advocate the revolution among the Chinese of Malaysia and Singapore, the local Chinese community was politically fragmented. There were often clashes between factions on the basis of clans and Ancestral home. The disorganization obstructed the spread of revolutionary ideas, and the clashes between the clans hindered both the economic progress of the Chinese as well as cooperation between Chinese organizations.

While hosting the establishment ceremony of the Tongmenghui branch in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 1906, Sun Yat-sen warned that the disorganization of the local Chinese would eventually lead to the collapse of the local Chinese community. To improve the situation, the Tongmenghui initiated different kinds of propaganda, such as magazines, night schools, and dramatic performances; groups with different ancestral homes in mainland China were allowed to work with Sun Yat-sen for the revolution. This allowed Chinese with different ancestral homes to learn to understand each other and cooperate as a team in order to solve common difficulties. Through various connections, both cooperation among the local Chinese and nationalist feelings began develop.

One of the most important developments was the spread of Standard Chinese in the schools of Malay Peninsula and Singapore. This educational reform was intended to break the tradition of lecturing students in the (often obscure) dialect of their particular ancestral homeland in mainland China. As a result, Chinese from different ancestral homes learned a common language.

The revolutionary trend of Sun Yat-sen brought new ideas to the Malay peninsula and Singapore, which clashed with the old traditions of Chinese society. The ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity spread widely and encouraged, among other things, the establishment of all-girl schools. Women were allowed to participate in social activities and to join the revolution.

After the success of the revolution, the Nationalist Party was established in August 13, 1912. With the permission of the British colonial government, the Malaya branch of the Nationalist Party was established. Later, when the British authorities recognized that the Nationalist Party did not intend to resist its rule, they gave their permission to establish another Nationalist Party branch in Singapore on December 18. The Nationalist Party continued to engage in legal activitiies in Malaya until 1925, when its registration was cancelled because it had provided insufficient information, according to the local government. However, the Nationalist Party continued to be active in Malaysia, albeit secretly. The activities of the Nationalist Party in Malaysia and Singapore were influential during the Second Sino-Japanese War and on the post-war political movements in Malaysia and Singapore.

Evaluation

In the early years of Republic of China, the intellectuals in China and the participants of the Xinhai Revolution were excited by the revolution's success in overthrowing the Manchu Dynasty, and they had high hopes for the revolution. However, because democracy had been only partially realized after the Xinhai Revolution, people began to develop different perspectives. Sun Yat-sen mentioned the following in a letter to the Russian ambassador in 1921 "Now our friends recognize that my resignation was a huge political mistake". Sun also urged in his will that "The revolution is not yet successful, the comrades still need to strive for the future". The intellectuals at the time thought that a political revolution alone could not save China and that preparations had to be made for a cultural reformation.

After the 1920s, the two dominant parties — the Nationalist Party and the Communist Party — evaluated the Xinhai Revolution quite differently. The Nationalist Party recognized Sun Yat-sen as the Father of the Nation and as the leader who led the Xinhai Revolution to success. They had a high opinion of the Xinhai Revolution, viewing the Xinhai Revolution as the starting point of the modern history of China, and as the key element that enabled China to develop into a democratic and modern nation.

On the other hand, the Communist Party thought that the Xinhai Revolution merely overthrew the totalitarian rule of the Qing Dynasty. It did not oppose imperialism or feudalism because the bourgeois class was (allegedly) compromising and feeble, and therefore it did not create a truly republican system. Land had not been redistributed equally, and a transformation of society had not been achieved. The revolution ended up yielding to the Western powers, and it compromised with Yuan Shikai, who represented the old regime. At the same time however, they recognized that, if viewed as a first stage of reform, the Xinhai Revolution had achieved much and had set the stage for further revolutions. Liu Shaoqi was quoted as saying that the "Xinhai Revolution inserted the concept of a republic into common people". Zhou Enlai pointed out that "Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing rule, ended 2000 years of monarchy, and liberated the mind of people to a great extent, and opened up the path for the development of future reovlution. This is a great victory". He Xiangning thought that "Xinhai Revolution was a great victory: it destroyed 2000 years of monarchy, and spread the seed of the thoughts of a republic among the people, and promoted new development for the revolutionary struggle of the Chinese people". Later Marxist historians mainly recognized the Xinhai Revolution as the Chinese bourgeois revolution, which is a necessary stage of revolution preceding a socialist revolution. These positive views of the Xinhai Revolution were common in Mainland China and Taiwan after the 1950s.

A change in the belief that the revolution had been a generally positive change began in late 1980s and 1990s. Zhang Shizhao was quoted as arguing that "When talking about the Xinhai Revolution, the theorist these days tends to overemphasize. The word ‘success’ was way overused". Chinese historians such as Li Zehou, Liu Zhaifu, and others thought that in the early 20th century, China would have been better off if it had pursued a gradual constitutional reform of the monarchy instead of engaging in a violent revolution. The former policy was said be better because it would have ensured China's steady development. The concept of constitutional monarchy advocated by Yuan Shikai, Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao, and Yang Du was more suitable for China at that time. The Taiwanese historians also began to re-examine some of the alleged "myths" of Xinhai Revolution, and began to re-evaluate the value of Xinhai Revolution and its effects.

Western scholars, Chinese specialists, and historians have researched the Xinhai Revolution to a great extent. Famous Chinese specialist John Fairbank evaluated the Xinhai Revolution as merely a "change of political system", which was "essentially a failure". Gao Muke thought that Xinhai Revolution was a revolution that was greater than all its leaders, and was a "revolution without a real leader".

Professor Nathaniel Peffer of the Columbia University criticized the Xinhai Revolution and its attempt on building a republic:

The replica of American system of republic built by China in 1911 was absurd and ridiculous. [...] That system of republic was a major failure, because it had no basis in Chinese history, tradition, politics, system, nature, beliefs or habits. It was a foreign product, hollow, and was forcibly added on China. It was quickly removed as the time passed. It did not represent political thoughts, but comics of political thoughts, coarse and premature comics. [...] This system of republic ended miserably, which meant it failed miserably. However, the failure was not on the system of the republic [...] it was a whole generation.

See also

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- History of China

- Xinhai Lhasa Turmoil

- Kuomintang

Notes

^ a: Many of the Qing soldiers with Han background turned to support the revolution during the uprisings, so the actual casualties are hard to trace.

^ b: Clipping from Min Bao (People's Papers). Originally the publishing of Hua Xin Hui and was named "China of the Twentieth Century", it was renamed after the establishment of Tongmenhui.

Citations

- ↑ "Complete works of Sun Yat-sen"《總理全集》 First edition, page 920

- ↑ Dr Sun & 1911 Revolution: Wuchang Uprising — The Success of the Xinhai Revolution.

- ↑ Borst-Smith, Ernest F. (1912). Caught in the Chinese Revolution. T Fisher Unwin.

- ↑ "即由袁世凱以全權組織臨時共和政府

- ↑ Mayhew, Bradley and Michael Kohn. (2005). Tibet, p. 32. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

References

Primary sources

Secondary sources

English

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1991). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951:The Demise of the Lamaist state. University of California Prp. ISBN-13: 978-0-520-07590-0.

- Stavrianos, L.S. (1998). A Global History: From Prehistory to the 21st Century (7th Edition). Prentice Hall; 7 edition. ISBN-13: 978-0139238970.

Chinese

- Tang (唐), Degang (德剛) (1998). The Late 50 years of Qing: Yuan Shikai, Sun Yat-sen and Xinhai Revolution. Taipei: Yuanliu (遠流). ISBN 957-32-3513.

- Tang (唐), Degang (德剛) (2002). The Rule of Yuan Shikai (袁氏當國). Taipei: Yuanliu (遠流). ISBN 957-32-4680-5.

- Zhang (張), Yufa (玉法) (1998). The History of the Republic of China (中華民國史稿). Taipei: Lianjin (聯經). ISBN 957-08-1826-3.

- Lin (林), Yusheng (毓生) (1983). <The Anti-tradition Trends of May Forth Era and the Future of Libertarianism in China> included in "Personage and their thoughts" (<五四時代的激烈反傳統思想與中國自由主義的前途> 收入"思想與人物"). Taipei: Lianjin (聯經).

- Zhou (周), Weimin (伟民); Tang (唐), Linlin (玲玲) (2002). The History of Cultural Interactions of China and Malaysia (中国和马来西亚文化交流史). Haikou: Hainan (海南). ISBN 7-5443-0682-8.

- Li (李), Zehou (澤厚); Liu (劉), Zhaifu (再復) (1999). A Farewell to the Revolutions - Records of Discussions in 20th Century China (告別革命-二十世紀中國對談錄). Taipei: Maitian (麥田). ISBN957-708-735-3.