X-ray

X-radiation (composed of X-rays) is a form of electromagnetic radiation. X-rays have a wavelength in the range of 10 to 0.001 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30 petahertz to 30 exahertz (30 × 1015 Hz to 30 × 1018 Hz) and energies in the range 120 eV to 120 keV. They are shorter in wavelength than UV rays. In many languages, X-radiation is called Röntgen radiation after one of its first investigators, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen.

X-rays are primarily used for diagnostic radiography and crystallography. As a result, the term "X-ray" is metonymically used to refer to a radiographic image produced using this method, in addition to the method itself. X-rays are a form of ionizing radiation and as such can be dangerous.

X-rays span 3 decades in wavelength, frequency and energy. From about 0.12 to 12 keV they are classified as soft x-rays, and from about 12 to 120 keV as hard X-rays, due to their penetrating abilities.

The distinction between x-rays and gamma rays has changed in recent decades. Originally, the electromagnetic radiation emitted by x-ray tubes, called x-rays, generally had a longer wavelength than the electromagnetic radiation emitted by radioactive nuclei, called gamma rays.[3] So older literature distinguished between x- and gamma radiation on the basis of wavelength, with radiation shorter than some arbitrary wavelength, such as 10-11 m, defined as gamma rays.[4] However, as shorter wavelength continuous spectrum 'x-ray' sources such as linear accelerators and longer wavelength 'gamma ray' emitters were discovered, the wavelength bands largely overlapped. So the two types of radiation are now usually defined by their origin: x-rays are emitted by electrons outside the nucleus, while gamma rays are emitted by the nucleus.[3][5][6][7]

Contents[hide] |

Units of measure and exposure

The measure of x-rays ionizing ability is called the exposure:

- The coulomb per kilogram (C/kg) is the SI unit of ionizing radiation exposure, and measures the amount of radiation required to create 1 coulomb of charge of each polarity in 1 kilogram of matter.

- The roentgen (R) is an obsolete older traditional unit of exposure, which represented the amount of radiation required to create 1 esu of charge of each polarity in 1 cubic centimeter of dry air. 1 roentgen = 2.58×10−4 C/kg

However, the effect of ionizing radiation on matter (especially living tissue) is more closely related to the amount of energy deposited rather than the charge. This is called the absorbed dose:

- The gray (Gy) which has units of (J/C), is the SI unit of absorbed dose which is the amount of radiation required to deposit 1 joule of energy in 1 kilogram of any kind of matter.

- The rad (roentgen absorbed dose) is the (obsolete) corresponding traditional unit, equal to 0.01 J deposited per kg. 100 rad = 1 Gy.

The equivalent dose is the measure of the biological effect of radiation on human tissue. For x-rays it is equal to the absorbed dose.

- The sievert (Sv) is the SI unit of equivalent dose, which for x-rays is equal to the gray (Gy).

- The rem (roentgen equivalent man) is the traditional unit of equivalent dose. For x-rays it is equal to the rad or 0.01 J of energy deposited per kg. 1 sievert = 100 rem.

Medical x-rays are a major source of manmade radiation exposure, accounting for 58% in the USA in 1987, but since most radiation exposure is natural (82%) it only accounts for 10% of total USA radiation exposure.[8]

Reported dosage due to dental X-rays seems to vary significantly. Depending on the source, a typical dental X-ray of a human results in an exposure of perhaps, 3[9], 40[10], 300[11], or as many as 900[12] mrems (30 to 9,000 μSv).

Medical physics

| Target | Kβ₁ | Kβ₂ | Kα₁ | Kα₂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | 0.17566 | 0.17442 | 0.193604 | 0.193998 |

| Co | ||||

| Ni | 0.15001 | 0.14886 | 0.165791 | 0.166175 |

| Cu | 0.139222 | 0.138109 | 0.154056 | 0.154439 |

| Zr | 0.070173 | 0.068993 | 0.078593 | 0.079015 |

| Mo | 0.063229 | 0.062099 | 0.070930 | 0.071359 |

| W | ||||

| Re |

X-rays are generated by an x-ray tube, a vacuum tube that uses a high voltage to accelerate electrons released by a hot cathode to a high velocity. The high velocity electrons collide with a metal target, the anode, creating the x-rays.[14] In medical x-ray tubes the target is usually tungsten or a more crack-resistant alloy of rhenium (5%) and tungsten (95%), but sometimes molybdenum for more specialized applications, such as when soft X-rays are needed as in mammography. In crystallography, a copper target is most common, with cobalt often being used when fluorescence from iron content in the sample might otherwise present a problem.

The maximum energy of the produced x-ray photon in keV is limited by the energy of the incident electron, which is equal to the voltage on the tube, so an 80 kV tube can't create higher than 80 keV x-rays. When the electrons hit the target, x-rays are created by two different atomic processes:

- X-ray fluorescence: If the electron has enough energy it can knock an orbital electron out of the inner shell of a metal atom, and as a result electrons from higher energy levels then fill up the vacancy and X-ray photons are emitted. This process produces a discrete spectrum of x-ray frequencies, called spectral lines. The spectral lines generated depends on the target (anode) element used and thus are called characteristic lines. Usually these are transitions from upper shells into K shell (called K lines), into L shell (called L lines) and so on.

- Bremsstrahlung: This is radiation given off by the electrons as they are scattered by the strong electric field near the high-Z (proton number) nuclei. These x-rays have a continuous spectrum. The intensity of the x-rays increases linearly with decreasing frequency, from zero at the energy of the incident electrons, the voltage on the X-ray tube.

So the resulting output of a tube consists of a continuous bremsstrahlung spectrum falling off to zero at the tube voltage, plus several spikes at the characteristic lines. The voltages used in diagnostic x-ray tubes, and thus the highest energies of the x-rays, range from roughly 20 to 150 kV.[15]

In medical diagnostic applications, the low energy (soft) x-rays are unwanted, since they are totally absorbed by the body, increasing the dose. So a thin metal (often aluminum) sheet is placed over the window of the x-ray tube, filtering out the low energy end of the spectrum. This is called hardening the beam. Very hard X-rays overlap with the range of "long"-wavelength (lower energy) gamma rays, however the distinction between the two terms in medicine depends on the source of the radiation, not its wavelength; X-ray photons are generated by energetic electron processes, gamma rays by transitions within atomic nuclei.

Both x-ray production processes are extremely inefficient (~1%) and thus to produce a usable flux of X-rays plenty of energy has to be wasted into heat, which has to be removed from the x-ray tube.

Radiographs obtained using X-rays can be used to identify a wide spectrum of pathologies. Due to their short wavelength, in medical applications, X-rays act more like a particle than a wave. This is in contrast to their application in crystallography, where their wave-like nature is most important.

To take an X-ray of the bones, short X-ray pulses are shot through a body with radiographic film behind. The bones absorb the most photons by the photoelectric process, because they are more electron-dense. The X-rays that do not get absorbed turn the photographic film from white to black, leaving a white shadow of bones on the film.

To generate an image of the cardiovascular system, including the arteries and veins (angiography) an initial image is taken of the anatomical region of interest. A second image is then taken of the same region after iodinated contrast material has been injected into the blood vessels within this area. These two images are then digitally subtracted, leaving an image of only the iodinated contrast outlining the blood vessels. The radiologist or surgeon then compares the image obtained to normal anatomical images to determine if there is any damage or blockage of the vessel.

A specialized source of x-rays which is becoming widely used in research is synchrotron radiation, which is generated by particle accelerators. Its unique features are brightness many orders of magnitude greater than x-ray tubes, wide spectrum, high collimation, and linear polarization.[16]

Detectors

Photographic plate

The detection of X-rays is based on various methods. The most commonly known methods are a photographic plate, X-ray film in a cassette, and rare earth screens. Regardless of what is "catching" the image, they are all categorized as "Image Receptors" (IR).

Before computers and before digital imaging, a photographic plate was used to produce radiographic images. The images were produced right on the glass plates. Film replaced these plates and was used in hospitals to produce images. Now computed & digital radiography has started to replace film in medicine, though film technology remains in use in industrial radiography processes (e.g. to inspect welded seams). Photographic plates are a thing of history, and their replacement (intensifying screens) is now becoming part of that same history. Silver (necessary to the radiographic & photographic industry) is a non-renewable resource, that has now been replaced by digital (DR) and computed (CR) technology. Where film required wet processing facilities, these new technologies do not. Archiving of these new technologies also saves space.

Since photographic plates are sensitive to X-rays, they provide a means of recording the image, but require a lot of exposure (to the patient), so intensifying screens were devised. They allow a lower dose to the patient, because the screens take the X-ray information and intensify it so that it can be recorded on film positioned next to the intensifying screen.

The part of the patient to be X-rayed is placed between the X-ray source and the image receptor to produce a shadow of the internal structure of that particular part of the body. X-rays are somewhat blocked ("attenuated") by dense tissues such as bone, and pass more easily through soft tissues. Those areas where the X-rays strike the image receptor will produce photographic density (ie. it will turn black when developed). So where the X-rays pass through "soft" parts of the body such as organs, muscle, and skin, the plate or film turns black.

Contrast compounds containing barium or iodine, which are radiopaque, can be ingested in the gastrointestinal tract (barium) or injected in the artery or veins to highlight these vessels. The contrast compounds have high atomic numbered elements in them that (like bone) essentially block the X-rays and hence the once hollow organ or vessel can be more readily seen. In the pursuit of a non-toxic contrast material, many types of high atomic number elements were evaluated. For example, the first time the forefathers used contrast it was chalk, and was used on a cadaver's vessels. Unfortunately, some elements chosen proved to be harmful – for example, thorium was once used as a contrast medium (Thorotrast) – which turned out to be toxic in some cases (causing injury and occasionally death from the effects of thorium poisoning). Modern contrast material has improved, and while there is no way to determine who may have a sensitivity to the contrast, the incidence of "allergic-type reactions" are low. (The risk is comparable to that associated with penicillin.)

Photostimulable phosphors (PSPs)

An increasingly common method of is the use of photostimulated luminescence (PSL), pioneered by Fuji in the 1980s. In modern hospitals a photostimulable phosphor plate (PSP plate) is used in place of the photographic plate. After the plate is X-rayed, excited electrons in the phosphor material remain 'trapped' in 'colour centres' in the crystal lattice until stimulated by a laser beam passed over the plate surface. The light given off during laser stimulation is collected by a photomultiplier tube and the resulting signal is converted into a digital image by computer technology, which gives this process its common name, computed radiography (also referred to as digital radiography). The PSP plate can be used over and over again, and existing X-ray equipment requires no modification to use them.

Geiger counter

Initially, most common detection methods were based on the ionization of gases, as in the Geiger-Müller counter: a sealed volume, usually a cylinder, with a mica, polymer or thin metal window contains a gas, and a wire, and a high voltage is applied between the cylinder (cathode) and the wire (anode). When an X-ray photon enters the cylinder, it ionizes the gas and forms ions and electrons. Electrons accelerate toward the anode, in the process causing further ionization along their trajectory. This process, known as a Townsend avalanche, is detected as a sudden current, called a "count" or "event".

Ultimately, the electrons form a virtual cathode around the anode wire, drastically reducing the electric field in the outer portions of the tube. This halts the collisional ionizations and limits further growth of avalanches. As a result, all "counts" on a Geiger counter are the same size and it can give no indication as to the particle energy of the radiation, unlike the proportional counter. The intensity of the radiation is measurable by the Geiger counter as the counting-rate of the system.

In order to gain energy spectrum information, a diffracting crystal may be used to first separate the different photons. The method is called wavelength dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (WDX or WDS). Position-sensitive detectors are often used in conjunction with dispersive elements. Other detection equipment that is inherently energy-resolving may be used, such as the aforementioned proportional counters. In either case, use of suitable pulse-processing (MCA) equipment allows digital spectra to be created for later analysis.

For many applications, counters are not sealed but are constantly fed with purified gas, thus reducing problems of contamination or gas aging. These are called "flow counters".

Scintillators

Some materials such as sodium iodide (NaI) can "convert" an X-ray photon to a visible photon; an electronic detector can be built by adding a photomultiplier. These detectors are called "scintillators", filmscreens or "scintillation counters". The main advantage of using these is that an adequate image can be obtained while subjecting the patient to a much lower dose of X-rays.

Image intensification

X-rays are also used in "real-time" procedures such as angiography or contrast studies of the hollow organs (e.g. barium enema of the small or large intestine) using fluoroscopy acquired using an X-ray image intensifier. Angioplasty, medical interventions of the arterial system, rely heavily on X-ray-sensitive contrast to identify potentially treatable lesions.

Direct semiconductor detectors

Since the 1970s, new semiconductor detectors have been developed (silicon or germanium doped with lithium, Si(Li) or Ge(Li)). X-ray photons are converted to electron-hole pairs in the semiconductor and are collected to detect the X-rays. When the temperature is low enough (the detector is cooled by Peltier effect or even cooler liquid nitrogen), it is possible to directly determine the X-ray energy spectrum; this method is called energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX or EDS); it is often used in small X-ray fluorescence spectrometers. These detectors are sometimes called "solid state detectors". Cadmium telluride (CdTe) and its alloy with zinc, cadmium zinc telluride detectors have an increased sensitivity, which allows lower doses of X-rays to be used.

Practical application in medical imaging didn't start taking place until the 1990s. Currently amorphous selenium is used in commercial large area flat panel X-ray detectors for mammography and chest radiography. Current research and development is focused around pixel detectors, such as CERN's energy resolving Medipix detector.

Note: A standard semiconductor diode, such as a 1N4007, will produce a small amount of current when placed in an X-ray beam. A test device once used by Medical Imaging Service personnel was a small project box that contained several diodes of this type in series, which could be connected to an oscilloscope as a quick diagnostic.

Silicon drift detectors (SDDs), produced by conventional semiconductor fabrication, now provide a cost-effective and high resolving power radiation measurement. Unlike conventional X-ray detectors, such as Si(Li)s, they do not need to be cooled with liquid nitrogen.

Scintillator plus semiconductor detectors (indirect detection)

With the advent of large semiconductor array detectors it has become possible to design detector systems using a scintillator screen to convert from X-rays to visible light which is then converted to electrical signals in an array detector. Indirect Flat Panel Detectors (FPDs) are in widespread use today in medical, dental, veterinary and industrial applications. A common form of these detectors is based on amorphous silicon TFT/photodiode arrays.

The array technology is a variant on the amorphous silicon TFT arrays used in many flat panel displays, like the ones in computer laptops. The array consists of a sheet of glass covered with a thin layer of silicon that is in an amorphous or disordered state. At a microscopic scale, the silicon has been imprinted with millions of transistors arranged in a highly ordered array, like the grid on a sheet of graph paper. Each of these thin film transistors (TFTs) are attached to a light-absorbing photodiode making up an individual pixel (picture element). Photons striking the photodiode are converted into two carriers of electrical charge, called electron-hole pairs. Since the number of charge carriers produced will vary with the intensity of incoming light photons, an electrical pattern is created that can be swiftly converted to a voltage and then a digital signal, which is interpreted by a computer to produce a digital image. Although silicon has outstanding electronic properties, it is not a particularly good absorber of X-ray photons. For this reason, X-rays first impinge upon scintillators made from eg. gadolinium oxysulfide or caesium iodide. The scintillator absorbs the X-rays and converts them into visible light photons that then pass onto the photodiode array.

Visibility to the human eye

While generally considered invisible to the human eye, in special circumstances X-rays can be visible.[17] Brandes, in an experiment a short time after Röntgen's landmark 1895 paper, reported after dark adaptation and placing his eye close to an X-ray tube, seeing a faint "blue-gray" glow which seemed to originate within the eye itself.[18] Upon hearing this, Röntgen reviewed his record books and found he too had seen the effect. When placing an X-ray tube on the opposite side of a wooden door Röntgen had noted the same blue glow, seeming to emanate from the eye itself, but thought his observations to be spurious because he only saw the effect when he used one type of tube. Later he realized that the tube which had created the effect was the only one powerful enough to make the glow plainly visible and the experiment was thereafter readily repeatable. The knowledge that X-rays are actually faintly visible to the dark-adapted naked eye has largely been forgotten today; this is probably due to the desire not to repeat what would now be seen as a recklessly dangerous and potentially harmful experiment with ionizing radiation. It is not known what exact mechanism in the eye produces the visibility: it could be due to conventional detection (excitation of rhodopsin molecules in the retina), direct excitation of retinal nerve cells, or secondary detection via, for instance, X-ray induction of phosphorescence in the eyeball with conventional retinal detection of the secondarily produced visible light.

Though X-rays are invisible it is possible to see the ionization of the air molecules if the intensity of the X-ray beam is high enough. The beamline from the wiggler at the ID11 at ESRF is one example of such high intensity [19]

Medical uses

Since Röntgen's discovery that X-rays can identify bony structures, X-rays have been developed for their use in medical imaging. Radiology is a specialized field of medicine. Radiologists employ radiography and other techniques for diagnostic imaging. This is probably the most common use of X-ray technology.

X-rays are especially useful in the detection of pathology of the skeletal system, but are also useful for detecting some disease processes in soft tissue. Some notable examples are the very common chest X-ray, which can be used to identify lung diseases such as pneumonia, lung cancer or pulmonary edema, and the abdominal X-ray, which can detect ileus (blockage of the intestine), free air (from visceral perforations) and free fluid (in ascites). In some cases, the use of X-rays is debatable, such as gallstones (which are rarely radiopaque) or kidney stones (which are often visible, but not always). Also, traditional plain X-rays pose very little use in the imaging of soft tissues such as the brain or muscle. Imaging alternatives for soft tissues are computed axial tomography (CAT or CT scanning), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound. Since 2005, X-rays are listed as a carcinogen by the U.S. government.[20]

Radiotherapy, a curative medical intervention, now used almost exclusively for cancer, employs higher energies of radiation.

Shielding against X-Rays

Lead is the most common shield agains X-Rays because of its high density (11340 kg/m3), its easiness of installation and low price.

The following table shows the recommended thickness of Lead in function of X-Ray energy

(Recommendations by the Second International Congress of Radiology.)[21]

| X-Rays generated by peak voltages not exceeding |

Minimum thickness of Lead |

|---|---|

| 75 kV | 1.0 mm |

| 100 kV | 1.5 mm |

| 125 kV | 2.0 mm |

| 150 kV | 2.5 mm |

| 175 kV | 3.0 mm |

| 200 kV | 4.0 mm |

| 225 kV | 5.0 mm |

| 300 kV | 9.0 mm |

| 400 kV | 15.0 mm |

| 500 kV | 22.0 mm |

| 600 kV | 34.0 mm |

| 900 kV | 51.0 mm |

Other uses

Other notable uses of X-rays include

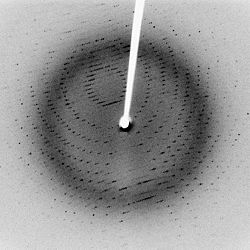

- X-ray crystallography in which the pattern produced by the diffraction of X-rays through the closely spaced lattice of atoms in a crystal is recorded and then analyzed to reveal the nature of that lattice. A related technique, fiber diffraction, was used by Rosalind Franklin to discover the double helical structure of DNA.[22]

- X-ray astronomy, which is an observational branch of astronomy, which deals with the study of X-ray emission from celestial objects.

- X-ray microscopic analysis, which uses electromagnetic radiation in the soft X-ray band to produce images of very small objects.

- X-ray fluorescence, a technique in which X-rays are generated within a specimen and detected. The outgoing energy of the X-ray can be used to identify the composition of the sample.

- Industrial radiography uses x-rays for inspection of industrial parts, particularly welds.

- Paintings are often X-rayed to reveal the underdrawing and pentimenti or alterations in the course of painting, or by later restorers. Many pigments such as lead white show well in X-ray photographs.

- Airport security luggage scanners use x-rays for inspecting the interior of luggage for security threats before loading on aircraft.

History

X-rays were discovered emanating from Crookes tubes, experimental discharge tubes invented around 1875, by scientists investigating the cathode rays, that is energetic electron beams, that were first created in the tubes. Crookes tubes created electrons by ionization of the residual air in the tube by a high DC voltage of anywhere between a few kilovolts and 100 kV. This voltage accelerated the electrons coming from the cathode to a high enough velocity that they created x-rays when they struck the anode or the glass wall of the tube. Many of the early Crookes tubes undoubtedly radiated x-rays, because early researchers noticed effects that were attributable to them, as detailed below, before Wilhelm Röntgen first systematically studied them in 1895. Among the important early researchers in X-rays were Ivan Pulyui, William Crookes, Johann Wilhelm Hittorf, Eugen Goldstein, Heinrich Hertz, Philipp Lenard, Hermann von Helmholtz, Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison, Charles Glover Barkla, Max von Laue, and Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen.

Wilhelm Röntgen

On November 8, 1895, German physics professor Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, stumbled on x-rays while experimenting with Lenard and Crookes tubes and began studying them. He wrote an initial report "On a new kind of ray: A preliminary communication" and on December 28, 1895 submitted it to the Würzburg's Physical-Medical Society journal.[23] This was the first paper written on X-rays. Röntgen referred to the radiation as "X", to indicate that it was an unknown type of radiation. The name stuck, although (over Röntgen's great objections), many of his colleagues suggested calling them Röntgen rays. They are still referred to as such in many languages, including German. Röntgen received the first Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery.

There are conflicting accounts of his discovery because Röntgen had his lab notes burned after his death, but this is a likely reconstruction by his biographers.[24] Röntgen was investigating cathode rays with a fluorescent screen painted with barium platinocyanide and a Crookes tube which he had wrapped in black cardboard so the visible light from the tube wouldn't interfere. He noticed a faint green glow from the screen, about 1 meter away. The invisible rays coming from the tube to make the screen glow were passing through the cardboard. He found they could also pass through books and papers on his desk. Röntgen threw himself into investigating these unknown rays systematically. Two months after his initial discovery, he published his paper.

Röntgen discovered its medical use when he saw a picture of his wife's hand on a photographic plate formed due to X-rays. His wife's hand's photograph was the first ever photograph of a human body part using X-rays.

Johann Hittorf

German physicist Johann Hittorf (1824 – 1914), a coinventor and early researcher of the Crookes tube, found when he placed unexposed photographic plates near the tube, that some of them were flawed by shadows, though he did not investigate this effect.

Ivan Pulyui

In 1877 Ukranian-born Pulyui, a lecturer in experimental physics at the University of Vienna, constructed various designs of vacuum discharge tube to investigate their properties.[25] He continued his investigations when appointed professor at the Prague Polytechnic and in 1886 he found that that sealed photographic plates became dark when exposed to the emanations from the tubes. Early in 1896, just a few weeks after Röntgen published his first X-ray photograph, Pulyui published high-quality x-ray images in journals in Paris and London.[25] Although Pulyui had studied with Röntgen at the University of Strasbourg in the years 1873-75, his biographer Gaida (1997) asserts that his subsequent research was conducted independently.[25]

The first medical X-ray made in the United States was obtained using a discharge tube of Pulyui's design. In January 1896, on reading of Röntgen's discovery, Frank Austin of Dartmouth College tested all of the discharge tubes in the physics laboratory and found that only the Pulyui tube produced X-rays. This was a result of Pulyui's inclusion of an oblique "target" of mica, used for holding samples of fluorescent material, within the tube. On 3 February 1896 Gilman Frost, professor of medicine at the college, and his brother Edwin Frost, professor of physics, exposed the wrist of Eddie McCarthy, whom Edwin had treated some weeks earlier for a fracture, to the x-rays and collected the resulting image of the broken bone on gelatin photographic plates obtained from Howard Langill, a local photographer also interested in Röntgen's work.[26]

Nikola Tesla

In April 1887, Nikola Tesla began to investigate X-rays using high voltages and tubes of his own design, as well as Crookes tubes. From his technical publications, it is indicated that he invented and developed a special single-electrode X-ray tube [27] [28], which differed from other X-ray tubes in having no target electrode. The principle behind Tesla's device is called the Bremsstrahlung process, in which a high-energy secondary X-ray emission is produced when charged particles (such as electrons) pass through matter. By 1892, Tesla performed several such experiments, but he did not categorize the emissions as what were later called X-rays. Tesla generalized the phenomenon as radiant energy of "invisible" kinds.[29] [30] Tesla stated the facts of his methods concerning various experiments in his 1897 X-ray lecture [31] before the New York Academy of Sciences. Also in this lecture, Tesla stated the method of construction and safe operation of X-ray equipment. His X-ray experimentation by vacuum high field emissions also led him to alert the scientific community to the biological hazards associated with X-ray exposure.[32]

Fernando Sanford

X-rays were generated and detected by Fernando Sanford (1854-1948), the foundation Professor of Physics at Stanford University, in 1891. From 1886 to 1888 he had studied in the Hermann Helmholtz laboratory in Berlin, where he became familiar with the cathode rays generated in vacuum tubes when a voltage was applied across separate electrodes, as previously studied by Heinrich Hertz and Philipp Lenard. His letter of January 6, 1893 (describing his discovery as "electric photography") to The Physical Review was duly published and an article entitled Without Lens or Light, Photographs Taken With Plate and Object in Darkness appeared in the San Francisco Examiner.[33]

Philipp Lenard

Philipp Lenard, a student of Heinrich Hertz, wanted to see whether cathode rays could pass out of the Crookes tube into the air. He built a Crookes tube (later called a 'Lenard tube') with a 'window' in the end made of thin aluminum, facing the cathode so the cathode rays would strike it.[34] He found that something came through, that would expose photographic plates and cause fluorescence. He measured the penetrating power of these rays through various materials. It has been suggested that at least some of these 'Lenard rays' were actually x-rays.[35] Hermann von Helmholtz formulated mathematical equations for X-rays. He postulated a dispersion theory before Röntgen made his discovery and announcement. It was formed on the basis of the electromagnetic theory of light[36]. However, he did not work with actual X-rays.

Thomas Edison

In 1895, Thomas Edison investigated materials' ability to fluoresce when exposed to X-rays, and found that calcium tungstate was the most effective substance. Around March 1896, the fluoroscope he developed became the standard for medical X-ray examinations. Nevertheless, Edison dropped X-ray research around 1903 after the death of Clarence Madison Dally, one of his glassblowers. Dally had a habit of testing X-ray tubes on his hands, and acquired a cancer in them so tenacious that both arms were amputated in a futile attempt to save his life. "At the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, an assassin shot President William McKinley twice at close range with a .32 caliber revolver." The first bullet was removed but the second remained lodged somewhere in his stomach. McKinley survived for some time and requested that Thomas Edison "rush an X-ray machine to Buffalo to find the stray bullet. It arrived but wasn't used . . . McKinley died of septic shock due to bacterial infection."[37]

The 20th century and beyond

The many applications of x-rays immediately generated enormous interest. Workshops began making specialized versions of Crookes tubes for generating x-rays, and these first generation cold cathode or Crookes x-ray tubes were used until about 1920.

Crookes tubes were unreliable. They had to contain a small quantity of gas (invariably air) as a current will not flow in such a tube if they are fully evacuated. However as time passed the X-rays caused the glass to absorb the gas, causing the tube to generate 'harder' x-rays until it soon stopped operating. Larger and more frequently used tubes were provided with devices for restoring the air, known as 'softeners'. This often took the form of a small side tube which contained a small piece of mica – a substance that traps comparatively large quantities of air within its structure. A small electrical heater heated the mica and caused it to release a small amount of air restoring the tube's efficiency. However the mica itself had a limited life and the restore process was consequently difficult to control.

In 1904, John Ambrose Fleming invented the thermionic diode valve (vacuum tube). This used a hot cathode which permitted current to flow in a vacuum. This idea was quickly applied x-ray tubes, and heated cathode x-ray tubes, called Coolidge tubes, replaced the troublesome cold cathode tubes by about 1920.

Two years later, physicist Charles Barkla discovered that X-rays could be scattered by gases, and that each element had a characteristic X-ray. He won the 1917 Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery. Max von Laue, Paul Knipping and Walter Friedrich observed for the first time the diffraction of X-rays by crystals in 1912. This discovery, along with the early works of Paul Peter Ewald, William Henry Bragg and William Lawrence Bragg gave birth to the field of X-ray crystallography. The Coolidge tube was invented the following year by William D. Coolidge which permitted continuous production of X-rays; this type of tube is still in use today.

The use of X-rays for medical purposes (to develop into the field of radiation therapy) was pioneered by Major John Hall-Edwards in Birmingham, England. In 1908, he had to have his left arm amputated owing to the spread of X-ray dermatitis[1].

The X-ray microscope was invented in the 1950s.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory, launched on July 23, 1999, has been allowing the exploration of the very violent processes in the universe which produce X-rays. Unlike visible light, which is a relatively stable view of the universe, the X-ray universe is unstable, it features stars being torn apart by black holes, galactic collisions, and novas, neutron stars that build up layers of plasma that then explode into space.

An X-ray laser device was proposed as part of the Reagan Administration's Strategic Defense Initiative in the 1980s, but the first and only test of the device (a sort of laser "blaster", or death ray, powered by a thermonuclear explosion) gave inconclusive results. For technical and political reasons, the overall project (including the X-ray laser) was de-funded (though was later revived by the second Bush Administration as National Missile Defense using different technologies).

See also

- Neutron radiation

- High energy X-rays

- X-ray crystallography

- X-ray astronomy

- X-ray machine

- X-ray microscope

- X-ray optics

- Backscatter X-ray

- Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

- Geiger counter

- N-ray

- Radiography

- X-ray vision

- X-ray absorption spectroscopy

References

- ↑ Kevles, Bettyann Holtzmann (1996). Naked to the Bone Medical Imaging in the Twentieth Century. Camden, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. pp19–22. ISBN 0813523583.

- ↑ Sample, Sharron (2007-03-27). "X-Rays". The Electromagnetic Spectrum. NASA. Retrieved on 2007-12-03.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dendy, P. P.; B. Heaton (1999). Physics for Diagnostic Radiology. USA: CRC Press. pp. p.12. ISBN 0750305916. http://books.google.com/books?id=1BTQvsQIs4wC&pg=PA12.

- ↑ Charles Hodgman, Ed. (1961). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 44th Ed.. USA: Chemical Rubber Co.. pp. p.2850.

- ↑ Feynman, Richard; Robert Leighton, Matthew Sands (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol.1. USA: Addison-Wesley. pp. p.2–5. ISBN 0201021161.

- ↑ L'Annunziata, Michael; Mohammad Baradei (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. pp. p.58. ISBN 0124366031. http://books.google.com/books?id=b519e10OPT0C&pg=PA58&dq=gamma+x-ray&lr=&as_brr=3&client=opera.

- ↑ Grupen, Claus; G. Cowan, S. D. Eidelman, T. Stroh (2005). Astroparticle Physics. Springer. pp. p.109. ISBN 3540253122.

- ↑ US National Research Council (2006). Health Risks from Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation, BEIR 7 phase 2. National Academies Press. pp. p.5, fig.PS–2. ISBN 030909156X. http://books.google.com/books?id=Uqj4OzBKlHwC&pg=PA5., data credited to NCRP (US National Committee on Radiation Protection) 1987

- ↑ http://www.doctorspiller.com/Dental%20_X-Rays.htm and http://www.dentalgentlecare.com/x-ray_safety.htm

- ↑ http://hss.energy.gov/NuclearSafety/NSEA/fire/trainingdocs/radem3.pdf

- ↑ http://www.hawkhill.com/114s.html

- ↑ http://www.solarstorms.org/SWChapter8.html and http://www.powerattunements.com/x-ray.html

- ↑ David R. Lide, ed.. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 75th edition. CRC Press. pp. 10–227. ISBN 0-8493-0475-X.

- ↑ Whaites, Eric; Roderick Cawson (2002). Essentials of Dental Radiography and Radiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. p.15–20. ISBN 044307027X. http://books.google.com/books?id=x6ThiifBPcsC&dq=radiography+kilovolt+x-ray+machine&lr=&as_brr=3&client=opera&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0.

- ↑ Bushburg, Jerrold; Anthony Seibert, Edwin Leidholdt, John Boone (2002). The Essential Physics of Medical Imaging. USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. p.116. ISBN 0683301187. http://books.google.com/books?id=VZvqqaQ5DvoC&pg=PT33&dq=radiography+kerma+rem+Sievert&lr=&as_brr=3&client=opera.

- ↑ Emilio, Burattini; Antonella Ballerna (1994). "Preface". Biomedical Applications of Synchrotron Radiation: Proceedings of the 128th Course at the International School of Physics -Enrico Fermi- 12-22 July 1994, Varenna, Italy: p.xv, IOS Press. Retrieved on 2008-11-11.

- ↑ Martin, Dylan (2005). "X-Ray Detection". University of Arizona Optical Sciences Center. Retrieved on 2008-05-19.

- ↑ Frame, Paul. "Wilhelm Röntgen and the Invisible Light". Tales from the Atomic Age. Oak Ridge Associated Universities. Retrieved on 2008-05-19.

- ↑ Eæements of Modern X-Ray Physics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd,. 2001. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-471-49858-0.

- ↑ 11th Report on Carcinogens

- ↑ Lead Shielding /// Alchemy's PDF

- ↑ Kasai, Nobutami; Masao Kakudo (2005). X-ray diffraction by macromolecules. Tokyo: Kodansha. pp. pp291–2. ISBN 3540253173.

- ↑ Stanton, Arthur (1896-01-23), "Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen On a New Kind of Rays: translation of a paper read before the Würzburg Physical and Medical Society, 1895" (– Scholar search), Nature 53: 274–6, doi:, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v53/n1369/pdf/053274b0.pdf

- ↑ Peters, Peter (1995). "W. C. Roentgen and the discovery of x-rays". Ch.1 Textbook of Radiology. Medcyclopedia.com, GE Healthcare. Retrieved on 2008-05-05.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Gaida, Roman; et al (1997). "Ukrainian Physicist Contributes to the Discovery of X-Rays". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Retrieved on 2008-04-06.

- ↑ Spiegel, Peter K (1995). "The first clinical X-ray made in America—100 years". American Journal of Roentgenology (Leesburg, VA: American Roentgen Ray Society) 164 (1): pp241–243. ISSN: 1546-3141. http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/reprint/164/1/241.pdf.

- ↑ Morton, William James, and Edwin W. Hammer, American Technical Book Co., 1896. Page 68.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 514,170, Incandescent Electric Light, and U.S. Patent 454,622, System of Electric Lighting.

- ↑ Cheney, Margaret, "Tesla: Man Out of Time ". Simon and Schuster, 2001. Page 77.

- ↑ Thomas Commerford Martin (ed.), "The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla". Page 252 "When it forms a drop, it will emit visible and invisible waves. [...]". (ed., this material originally appeared in an article by Nikola Tesla in The Electrical Engineer of 1894.)

- ↑ Nikola Tesla, "The stream of Lenard and Roentgen and novel apparatus for their production", Apr. 6, 1897.

- ↑ Cheney, Margaret, Robert Uth, and Jim Glenn, "Tesla, master of lightning". Barnes & Noble Publishing, 1999. Page 76. ISBN 0760710058

- ↑ Wyman, Thomas (Spring 2005). "Fernando Sanford and the Discovery of X-rays". "Imprint", from the Associates of the Stanford University Libraries: 5–15.

- ↑ Thomson, Joseph J. (1903). The Discharge of Electricity through Gasses. USA: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. p.182–186. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ryw4AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA138.

- ↑ Thomson, 1903, p.185

- ↑ Wiedmann's Annalen, Vol. XLVIII

- ↑ National Library of Medicine. "Could X-rays Have Saved President William McKinley?" Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/visibleproofs/galleries/cases/mckinley.html

- NASA Goddard Space Flight centre introduction to X-rays.

External links

- X-Ray Discussion Group

- An Example of a Radiograph

- A Photograph of an X-ray Machine

- An X-ray tube demonstration (Animation)

- 1896 Article: "On a New Kind of Rays"

- X-ray Tube in Action (Animation)

- Cathode Ray Tube Collection

|

||

|

||