Written Chinese

Written Chinese (Chinese: 中文; pīnyīn: zhōngwén) comprises the written symbols used to represent spoken Chinese and the rules about how they are arranged and punctuated. These symbols are commonly known as Chinese characters (traditional/simplified Chinese: 漢字/汉字; pinyin: hànzì). Chinese characters do not constitute an alphabet or a compact syllabary. Rather, the writing system is roughly logosyllabic; that is, each character generally represents either a complete one-syllable word (see logogram) or a single-syllable part of a word. The characters themselves are often composed of parts that may represent physical objects, abstract notions,[1] or pronunciation.[2]

Written Chinese is considered to be one of the world's oldest active, continuously used writing systems (cf."History of the Alphabet" citation below). Many current Chinese characters have been traced back to the 商 Shāng Dynasty about 1500 BCE, and the process of creating characters probably began some centuries earlier.[3] Chinese characters were standardized under the 秦 Qín dynasty (221–206 BCE).[4] Over the millennia, these characters have evolved into well-developed styles of Chinese calligraphy.[5]

Despite historical changes in pronunciation, Chinese speakers in disparate dialect groups can communicate in writing.[6] Some of the characters have also been adopted as part of the writing systems in other East Asian languages, such as Japanese and Korean.[7][8] Literacy requires the memorization of a great many characters: Educated Chinese know about 4,000,[9][10] while educated Japanese know about half that many.[8] The large number of Chinese characters has in part led to the adoption of Western alphabets as an auxiliary means of representing Chinese.[11]

Contents |

Structure

Written Chinese is not based predominantly on an alphabet or a compact syllabary.[1] Instead, Chinese characters are glyphs whose components may depict objects or represent abstract notions. Occasionally, a character consists of only one component; more commonly, two or more components are combined, using a variety of different principles, to form more complex characters. The best known exposition of Chinese character composition is the 說文解字/说文解字 Shuōwén Jiězì, compiled by 許慎/许慎 Xǔ Shèn around 120 CE. Since Xu Shen did not have access to Chinese characters in their earliest forms, his analysis cannot always be taken as authoritative.[12] Nonetheless, no later work has supplanted the Shuowen Jiezi in terms of breadth, and it is still relevant to etymological research today.[13]

According to the Shuowen Jiezi, Chinese characters are developed on six basic principles.[14] (These principles, though popularized by the Shuowen Jiezi, were developed earlier; the oldest known mention of them is in the 周禮/周礼 Zhōulǐ—literally, "Rites of Zhou"—a text from about 150 BCE.[15]) The first two principles produce simple characters, known as 文 wén:[14]

- 象形 xiàngxíng: Pictographs, in which the character is a graphical depiction of the object it denotes. Examples: 人 rén "person", 日 rì "sun", 木 mù "tree/wood".

- 指事 zhǐshì: Indicatives, or ideographs, in which the character represents an abstract notion. Examples: 上 shàng "up", 下 xià "down", 三 sān "three".

The remaining four principles produce complex characters historically called 字 zì (although this term is now generally used to refer to all characters, whether simple or complex). Of these four, two construct characters from simpler parts:[14]

- 會意/会意 huìyì: Logical aggregates, in which two or more parts are used for their meaning. This yields a composite meaning, which is then applied to the new character. Example: 東/东 dōng "east", which represents a sun rising in the trees.

- 形聲/形声 xíngshēng: Phonetic complexes, in which one part—often called the radical—indicates the general semantic category of the character (such as water-related or eye-related), and the other part is another character, used for its phonetic value. Example: 晴 qíng "clear/fair (weather)", which is composed of 日 rì "sun", and 青 qīng "blue/green", which is used for its pronunciation.

In contrast to the popular conception of Chinese as a primarily pictographic or ideographic language, the vast majority of Chinese characters (about 95 percent of the characters in the Shuowen Jiezi) are constructed as either logical aggregates or, more often, phonetic complexes.[2] In fact, some phonetic complexes were originally simple pictographs that were later augmented by the addition of a semantic root. An example is 炷 zhù "candle", which was originally a pictograph 主, a character that is now pronounced zhǔ and means "host". The character 火 huǒ "fire" was added to indicate that the meaning is fire-related.[16]

The last two principles do not produce new written forms; instead, they transfer new meanings to existing forms:[14]

- 轉注/转注 zhuǎnzhù: Transference, in which a character, often with a simple, concrete meaning takes on an extended, more abstract meaning. Example: 網/网 wǎng "net", which was originally a pictograph depicting a fishing net. Over time, it has taken on an extended meaning, covering any kind of lattice; for instance, it can be used to refer to a computer network.

- 假借 jiǎjiè: Borrowing, in which a character is used, either intentionally or accidentally, for some entirely different purpose. Example: 哥 gē "older brother", which is written with a character originally meaning "song/sing", now written 歌 gē. Once, there was no character for "older brother", so an otherwise unrelated character with the right pronunciation was borrowed for that meaning.

Chinese characters are generally written to fit into a square (except for simple characters such as 一 yī "one" for which this is not possible), even when they are composed of two simpler forms written side by side or top to bottom. In such cases, each form is compressed appropriately so that the entire character continues to fit into a square.[17]

Layout

Chinese characters conform to a roughly square frame and are not usually linked to one another, so they can be written in any direction in a square grid. Traditionally, Chinese is written in vertical columns from top to bottom; the first column is on the right side of the page, and the text runs toward the left. Text written in Classical Chinese also uses little or no punctuation. In such cases, sentence and phrase breaks are determined by context and rhythm.[18]

In modern times, the familiar Western layout of horizontal rows from left to right, read from the top of the page to the bottom, has become more popular, especially in the People's Republic of China (mainland China); the government there mandated left-to-right writing in 1955.[19] The Republic of China (Taiwan) followed suit in 2004.[20] Punctuation has also become more prevalent, whether the text is written in columns or rows. The punctuation marks are clearly influenced by their Western counterparts, although some marks are particular to Chinese: for example, the double and single quotation marks (『 』 and 「 」); the hollow period (。), which is otherwise used just like an ordinary full stop; and a special kind of comma called an enumeration comma (、), which is used to separate items in a list, as opposed to clauses in a sentence.

Signs are often a particularly challenging aspect of written Chinese layout, since they can be written either left to right or right to left (the latter can be thought of as the traditional layout with each "column" being one character high), as well as from top to bottom. It is not unusual to encounter all three orientations on signs on neighboring stores.[21]

Evolution

In 2003, tentative evidence was found at 賈湖/贾湖 Jiǎhú, an archaeological site in the 河南 Hénán province of China, for an early form of Chinese writing. Some symbols were found that bear striking resemblance to certain modern characters, such as 目 mù "eye". Since the Jiahu site dates from about 6600 BCE, it predates the earliest confirmed Chinese writing by about 4,000 years. The nature of this finding—whether it represents true writing (that is, a general mechanism for expression) or simply proto-writing (which comprises a limited set of symbols)—is still disputed. Critics contend that if the Jiahu finding really represented a direct ancestor of modern Chinese writing, it would indicate that Chinese writing remained relatively static for three millennia, at a time when China was sparsely populated.[22]

The first indisputable examples of Chinese writing, dating back to the Shāng Dynasty in the latter half of the second millennium BCE, are the oracle bones (primarily ox scapulae and turtle shells), originally used for divination. Characters were inscribed on the bones in order to frame a query; the bones were then heated over a fire, and the resulting cracks were interpreted to determine the answer to the query. Such characters are called 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén "shell-bone script" or oracle bone script.[3]

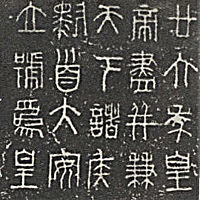

After the Shāng Dynasty, Chinese writing evolved into the form found on bronzeware made during the Western 周 Zhōu Dynasty (c 1066–770 BCE) and the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE), a kind of writing called 金文 jīnwén "metal script". Jinwen characters are more regular and angular than the embellished script of the oracle bone script. Later, in the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE), the script became still more regular, and settled on a form, called 六國文字/六国文字 liùguó wénzì "script of the six states", that Xu Shen used as source material in the Shuowen Jiezi. These characters were later embellished and stylized to yield the 篆書/篆书 zhuànshū seal script, which represents the oldest form of Chinese characters surviving to modern use. They are used principally for signature seals, or chops, which are often used in place of a signature, for Chinese documents and artwork. During the Qin dynasty, 李斯 Lǐ Sī promulgated the seal script as the standard throughout the empire, then newly unified.[4]

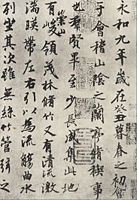

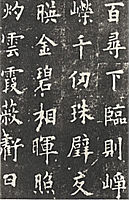

Seal script, in turn, evolved into the other surviving writing styles.[3][5] Clerical script (隸書/隶书 lìshū) developed first, after the seal script. In general, clerical script characters are "flat" in appearance, being wider than the seal script, which tends to be taller than it is wide. Compared with the seal script, clerical script characters are strikingly rectilinear. In running script (行書/行书 xíngshū), a semi-cursive form, the character parts begin to run into each other, although the characters themselves generally remain separate. There are some conventions in which characters deviate from their canonical forms in a consistent manner. Running script eventually evolved into grass script (草書/草书 cǎoshū), a fully cursive form, in which the characters are often entirely unrecognizable by their canonical forms. Grass script gives the impression of anarchy in its appearance, and there is indeed considerable freedom on the part of the calligrapher, but this freedom is circumscribed by conventional "abbreviations" in the forms of the characters. Regular script (楷書/楷书 kǎishū), a non-cursive form, is the most widely recognized script. In regular script, each stroke of each character is clearly drawn out from the others. Even though both the running and grass scripts appear to be derived as semi-cursive and cursive variants of regular script, it is in fact the regular script that was the last to develop.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Regular script is considered the archetype for Chinese writing, and forms the basis for most printed forms. In addition, regular script imposes a stroke order, which must be followed in order for the characters to be written correctly.[23] (Strictly speaking, this stroke order applies to the clerical, running, and grass scripts as well, but especially in the running and grass scripts, this order is occasionally deviated from.) Thus, for instance, the character 木 mù "wood" must be written starting with the horizontal stroke, drawn from left to right; next, the vertical stroke, from top to bottom, with a small hook toward the upper left at the end; next, the left diagonal stroke, from top to bottom; and lastly the right diagonal stroke, from top to bottom.[24]

Simplified and traditional Chinese

In the 20th century, written Chinese divided into two canonical forms, called 簡體字/简体字 jiǎntǐzì (simplified Chinese) and 繁體字/繁体字 fántǐzì (traditional Chinese). Simplified Chinese was developed in mainland China in order to make the characters faster to write (especially as some characters had as many as a few dozen strokes) and easier to memorize. The People's Republic of China has claimed that both goals have been achieved, but some external observers disagree. Little systematic study has been conducted on how simplified Chinese has affected the way Chinese people become literate; the only studies conducted before it was standardized in mainland China seem to have been statistical ones regarding how many strokes were saved on average in samples of running text.[25]

The simplified forms have also been criticized for being inconsistent. For instance, traditional 讓 ràng "allow" is simplified to 让, in which the phonetic on the right side is reduced from 17 strokes to just three. (The speech radical on the left has also been simplified.) However, the same phonetic is used in its full form, even in simplified Chinese, in such characters as 壤 rǎng "soil" and 齉 nàng "snuffle"; these forms remained uncontracted because they were relatively uncommon and would therefore represent a negligible stroke reduction.[26] On the other hand, some simplified forms are simply calligraphic abbreviations of long standing, as for example 万 wàn "ten thousand", for which the traditional Chinese form is 萬.[27]

Simplified Chinese is standard in the People's Republic of China, Singapore, and Malaysia. Traditional Chinese is retained in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and overseas Chinese communities (except Singapore and Malaysia).[28] Throughout this article, Chinese text is given in both simplified and traditional forms when they differ, with the traditional forms being given first.

Function

At the inception of written Chinese, spoken Chinese was monosyllabic; that is, Chinese words expressing independent concepts (objects, actions, relations, etc.) were usually one syllable. Each written character corresponded to one monosyllabic word.[30] The spoken language has since become polysyllabic,[31] but because modern polysyllabic words are usually composed of older monosyllabic words, Chinese characters have always been used to represent individual Chinese syllables.[32]

For over two thousand years, the prevailing written standard was a vocabulary and syntax rooted in Chinese as spoken around the time of Confucius (about 500 BCE), called Classical Chinese, or 文言文 wényánwén. Over the centuries, Classical Chinese gradually acquired some of its grammar and character senses from the various dialects. This accretion was generally slow and minor, however; by the 20th century, Classical Chinese was distinctly different from any contemporary dialect, and had to be learned separately.[33][34] Once learned, however, it was a common medium for communication between people speaking different dialects, many of which were mutually unintelligible by the end of the first millennium CE.[35] A Mandarin speaker might say yī, a Cantonese yat, and a Hokkienese tsit, but all three will understand the character 一 "one".[6]

Chinese dialects vary not only by pronunciation, but also, to a lesser extent, vocabulary and grammar.[36] Modern written Chinese, which replaced Classical Chinese as the written standard as an indirect result of the May Fourth Movement of 1919, is not technically bound to any single dialect; however, it most nearly represents the vocabulary and syntax of Mandarin, by far the most widespread Chinese dialect in terms of both geographical area and number of speakers.[37] This version of written Chinese is called Vernacular Chinese, or 白話/白话 báihuà (literally, "plain speech").[38] Despite its ties to the dominant Mandarin dialect, Vernacular Chinese also permits some communication between people of different dialects, limited by the fact that Vernacular Chinese expressions are often ungrammatical or unidiomatic in non-Mandarin dialects. This role may not differ substantially from the role of other lingua francas, such as Latin: For those trained in written Chinese, it serves as a common medium; for those untrained in it, the graphic nature of the characters is in general no aid to common understanding (characters such as "one" notwithstanding).[39] In this regard, Chinese characters may be considered a large and inefficient phonetic script.[40] However, Ghil'ad Zuckermann’s exploration of phono-semantic matching in Standard Mandarin concludes that the Chinese writing system is multifunctional, conveying both semantic and phonetic content.[41]

The variation in vocabulary among dialects has also led to the informal use of "dialectal characters", as well as standard characters that are nevertheless considered archaic by today's standards.[42] Cantonese is unique among non-Mandarin regional languages in having a written colloquial standard, used in Hong Kong and overseas, with a large number of unofficial characters for words particular to this dialect.[43] Written colloquial Cantonese has become quite popular in online chat rooms and instant messaging, although for formal written communications Cantonese speakers still normally use Vernacular Chinese.[44]

Other languages

Chinese characters were first introduced into Japanese sometime in the first half of the first millennium CE, probably from Chinese products imported into Japan through Korea.[7] At the time, Japanese had no native written system, and Chinese characters were used for the most part to represent Japanese words with the corresponding meanings, rather than similar pronunciations. A notable exception to this rule was the system of man'yōgana, which used a small set of Chinese characters to help indicate pronunciation. The man'yōgana later developed into the phonetic alphabets, hiragana and katakana.[45]

Chinese characters are called hànzì in Chinese, after the 漢/汉 Hàn Dynasty of China; in Japanese, this was pronounced kanji. In modern written Japanese, kanji are used for nouns, verb stems, and adjective stems, while hiragana are used for prefixes and suffixes; katakana are used exclusively for sound symbols, and for loans from other languages. The Jōyō Kanji, a list of kanji for common use standardized by the Japanese government, contains 1,945 characters—about half the number of characters commanded by literate Chinese.[8]

The role of Chinese characters in Korean and Vietnamese is much more limited. At one time, many Chinese characters (called hanja) were introduced into Korean for their meaning, just as in Japanese.[8] Today, written Korean relies almost exclusively on the phonetic hangul script, in which each syllable is written with two or three phonetic symbols that combine to form a single character. Similarly, the use of Chinese and Chinese-styled characters in the Vietnamese chữ nôm script has been almost entirely superseded by the quốc ngữ alphabet.[46]

Literacy

Because the majority of modern Chinese words contain more than one character, there are at least two measuring sticks for Chinese literacy: the number of characters known, and the number of words known. John DeFrancis, in the introduction to his Advanced Chinese Reader, estimates that a typical Chinese college graduate recognizes 4,000 to 5,000 characters, and 40,000 to 60,000 words.[9] Jerry Norman, in Chinese, places the number of characters somewhat lower, at 3,000 to 4,000.[10]

Variants

These counts are complicated by the tangled development of Chinese characters. In many cases, a single character came to be written in multiple ways; these variants are called allograph. This is analogous both to how Latin characters are written differently in different scripts (and cursive, and upper and lowercase: a/A), and to regional spelling differences, such as English "color/colour". This latter development was stemmed to an extent by the standardization of the seal script during the Qin dynasty, but soon started again. Although the Shuowen Jiezi lists 10,516 characters—9,353 of them unique (some of which may already have been out of use by the time it was compiled) plus 1,163 graphic variants—the 集韻/集韵 Jíyùn of the Northern 宋 Sòng Dynasty, compiled less than 1,000 years later in 1039, contains no fewer than 53,525 characters, most of them graphic variants.[47]

Dictionaries

Chinese is not based on an alphabet or syllabary, so Chinese dictionaries cannot be alphabetized or otherwise lexically ordered, as English dictionaries are. The need to arrange Chinese characters in order to permit efficient lookup has given rise to a considerable variety of ways to organize and index the characters.[48]

A traditional mechanism is the method of radicals, which uses a set of character roots. These roots, or radicals, generally but imperfectly align with the parts used to compose characters by means of logical aggregation and phonetic complex. A canonical set of 214 radicals was developed during the rule of the 康熙 Kāngxī emperor (around the year 1700); these are sometimes called the Kangxi radicals. The radicals are ordered first by stroke count (that is, the number of strokes required to write the radical); within a given stroke count, the radicals also have a prescribed order.[49]

Every Chinese character falls under the heading of exactly one of these 214 radicals.[48] In many cases, the radicals are themselves characters, which naturally come first under their own heading. All other characters under a given radical are ordered by the stroke count of the character. Usually, however, there are still many characters with a given stroke count under a given radical. At this point, characters are not given in any recognizable order; the user must locate the character by going through all the characters with that stroke count, typically listed for convenience at the top of the page on which they occur.[50]

Because the method of radicals is applied only to the written character, one need not know how to pronounce a character before looking it up; the entry, once located, usually gives the pronunciation. However, it is not always easy to identify which of the various roots of a character is the proper radical. Accordingly, dictionaries often include a list of hard to locate characters, indexed by total stroke count, near the beginning of the dictionary. Some dictionaries include almost one-seventh of all characters in this list.[48]

Other methods of organization exist, often in an attempt to address the shortcomings of the radical method, but are less common. For instance, it is common for a dictionary ordered principally by the Kangxi radicals to have an auxiliary index by pronunciation, expressed typically in either 漢語拼音/汉语拼音 hànyǔ pīnyīn or 注音符號/注音符号 zhùyīn fúhào.[51] This index points to the page in the main dictionary where the desired character can be found. Other methods use only the structure of the characters, such as the four-corner method, in which characters are indexed according to the kinds of strokes located nearest the four corners (hence the name of the method),[52] or the 倉頡/仓颉 Cāngjié method, in which characters are broken down into a set of 24 basic components.[53] Neither the four-corner method nor the Cangjie method requires the user to identify the proper radical, although many strokes or components have alternate forms, which must be memorized in order to use these methods effectively.

Transliteration and romanization

Chinese characters do not unambiguously indicate their pronunciation, even for any single dialect. It is therefore useful to be able to transliterate a dialect of Chinese into the Latin alphabet, for those who cannot read Chinese characters. However, transliteration was not always considered merely a way to record the sounds of any particular dialect of Chinese; it was once also considered a potential replacement for the Chinese characters. This was first prominently proposed during the May Fourth Movement, and it gained further support with the victory of the Communists in 1949. Immediately afterward, the mainland government began two parallel programs relating to written Chinese. One was the development of an alphabetic script for Mandarin, which was spoken by about two-thirds of the Chinese population;[36] the other was the simplification of the traditional characters—a process that would eventually lead to simplified Chinese. The latter was not viewed as an impediment to the former; rather, it would ease the transition toward the exclusive use of an alphabetic (or at least phonetic) script.[11]

By 1958, however, priority was given officially to simplified Chinese; a phonetic script, hanyu pinyin, had been developed, but its deployment to the exclusion of simplified characters was pushed off to some distant future date. The association between pinyin and Mandarin, as opposed to other dialects, may have contributed to this deferment.[54] It seems unlikely that pinyin will supplant Chinese characters anytime soon as the sole means of representing Chinese.[55]

Pinyin uses the Latin alphabet, along with a few diacritical marks, to represent the sounds of Mandarin in standard pronunciation. For the most part, pinyin uses vowel and consonant letters as they are used in Romance languages (and also in IPA). However, although 'b' and 'p', for instance, represent the voice/unvoiced distinction in some languages, such as French, they represent the unaspirated/aspirated distinction in Mandarin; Mandarin has few voiced consonants.[36] Also, the pinyin spellings for a few consonant sounds are markedly different from their spellings in other languages that use the Latin alphabet; for instance, pinyin 'q' and 'x' sound similar to English 'ch' and 'sh', respectively. Pinyin is not the sole transliteration scheme for Mandarin—there are also, for instance, the zhuyin fuhao, Wade-Giles, and Gwoyeu Romatzyh systems—but it is dominant in the Chinese-speaking world.[56] All transliterations in this article use the pinyin system.

References

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wieger.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 DeFrancis (1984), p. 84.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Norman, p. 64–65.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Norman, p. 63.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Norman, p. 65–70.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 DeFrancis (1984), p. 155–156.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Simon Ager (2007). "Japanese (Nihongo)". Omniglot. Retrieved on 2007-09-05.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Ramsey, p. 153.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 DeFrancis (1968).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Norman, p. 73.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ramsey, p. 143.

- ↑ Axel Schuessler (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 9.

- ↑ Norman, p. 67.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Wieger, p. 10–11.

- ↑ Lu Xun (1934). "An Outsider's Chats about Written Language". Retrieved on 2008-01-09.

- ↑ Wieger, p. 30.

- ↑ Björkstén, p. 52.

- ↑ Liang Huang et al (2002). "Statistical Part-of-Speech Tagging for Classical Chinese". Text, Speech, and Dialogue: Fifth International Conference: 115–122.

- ↑ Norman, p. 80.

- ↑ BBC News journalists (2004). "Taiwan Law Orders One-Way Writing". BBC. Retrieved on 2007-09-05.

- ↑ Ping-gam Go (1995). Understanding Chinese Characters (Third Edition). Simplex Publications. pp. P1–P31.

- ↑ Paul Rincon (2003). "Earliest Writing Found in China". BBC. Retrieved on 2007-09-05.

- ↑ McNaughton & Ying, p. 24.

- ↑ McNaughton & Ying, p. 43.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 151.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 152.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 147.

- ↑ Sebastien Bruggeman (2006). "Chinese Language Processing and Computing".

- ↑ Thorp, Robert L. "The Date of Tomb 5 at Yinxu, Anyang: A Review Article," Artibus Asiae (Volume 43, Number 3, 1981): 239–246. Page 240 & 245.

- ↑ Norman, p. 84.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1984), p. 177–188.

- ↑ Norman, p. 75.

- ↑ Norman, p. 83.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1984), p. 154.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 24–25.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Ramsey, p. 88.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 87.

- ↑ Norman, p. 109.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1984), p. 150.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1984), p. 72.

- ↑ Zuckermann, Ghil‘ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 255.

- ↑ Norman, p. 76.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 99.

- ↑ Wan Shun Eva Lam (2004). "Second Language Socialization in a Bilingual Chat Room: Global and Local Considerations". Learning, Language, and Technology 8 (3).

- ↑ Hari Raghavacharya et al (2006). "Perspectives for the Historical Information Retrieval with Digitized Japanese Classical Manuscripts". Proceedings of the 20th Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence.

- ↑ Norman, p. 79.

- ↑ Norman, p. 72.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 DeFrancis (1984), p. 92.

- ↑ Wieger, p. 19.

- ↑ Björkstén, p. 17–18.

- ↑ McNaughton & Ying, p. 20

- ↑ Gwo-En Wang, Jhing-Fa Wang (1994). "A New Hierarchical Approach for Recognition of Unconstrained Handwritten Numerals". IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 40 (3): 428–436. doi:.

- ↑ Hsi-Yao Su (2005). "Language Styling and Switching in Speech and Online Contexts: Identity and Language Ideologies in Taiwan". University of Texas at Austin.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 144–145.

- ↑ Ramsey, p. 153–154.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1984), p. 256.

Works cited

- J Björkstén (1994). Learn to Write Chinese Characters. Yale University Press.

- John DeFrancis (1968). Advanced Chinese Reader. The Murray Printing Co.

- John DeFrancis (1984). The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. University of Hawaii Press.

- William McNaughton and Li Ying (1999). Reading and Writing Chinese. Tuttle Publishing.

- Jerry Norman (1988). Chinese. Cambridge University Press.

- S Robert Ramsey (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton University Press.

- L Wieger (1915). Chinese Characters. Paragon Book Reprint Corp and Dover Publications, Inc (1965 reprint).

- History of the alphabet "The first pure alphabet emerged around 2000 BCE...Most alphabets in the world today either descend directly from this development..."

External links

- www.ArchChinese.com Free online stroke order animation for 6,000 simplified Chinese characters with pronunciations, example words and sentences; Generating writing worksheets with stroke sequences.

- Zhongwen.com Chinese characters and culture

- Cojak.org Online database of all characters in the Unicode repository. Each character is displayed in Simplified and Traditional forms, and contains Mandarin and Cantonese pronunciations, as well as the Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese pronunciations of characters where applicable; extensive dictionary entries are listed below each character.

- nciku Chinese dictionary with Chinese character handwriting recognition

- blabi.com Searchable database of characters and radicals, with stroke-order animations and phonetic representations

- Yue E Li and Christopher Upward. "Review of the process of reform in the simplification of Chinese Characters". (Journal of Simplified Spelling Society, 1992/2 pp. 14–16, later designated J13)

- Pinyin Annotator Add pinyin on top of any Chinese text. Mouse over any word to see English translation. Save output to OpenOffice Writer format. Prints nicely. Also adds pinyin to any Chinese web page.

- MDBG Chinese-English Dictionary Outstanding Chinese dictionary that recognizes multiple character words as well as individual character meaning. Full stroke order animation.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||