Woodrow Wilson

|

Woodrow Wilson

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921 |

|

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall |

| Preceded by | William Howard Taft |

| Succeeded by | Warren G. Harding |

|

34th Governor of New Jersey

|

|

| In office January 17, 1911 – March 1, 1913 |

|

| Preceded by | John Franklin Fort |

| Succeeded by | James Fairman Fielder |

|

13th President of Princeton University

|

|

| In office 1902 – 1910 |

|

| Preceded by | Francis L. Patton |

| Succeeded by | John Aikman Stewart |

|

|

|

| Born | December 28, 1856 Staunton, Virginia |

| Died | February 3, 1924 (aged 67) Washington, D.C. |

| Birth name | Thomas Woodrow Wilson |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Ellen Axson Wilson Edith Bolling Galt Wilson |

| Children | Margaret Woodrow Wilson Jessie Wilson Eleanor R. Wilson |

| Alma mater | Davidson College Princeton University The University of Virginia Johns Hopkins University (PhD) |

| Profession | Academic (History, Political science) |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Signature |  |

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924)[1] was the twenty-eighth President of the United States. A leading intellectual of the Progressive Era, he served as President of Princeton University and then became the Governor of New Jersey in 1910. With Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft dividing the Republican Party vote, Wilson was elected President as a Democrat in 1912. He proved highly successful in leading a Democratic Congress to pass major legislation that included the Federal Trade Commission, the Clayton Antitrust Act, the Federal Farm Loan Act, America's first-ever federal progressive income tax in the Revenue Act of 1913 and most notably the Federal Reserve Act.[2][3]

Narrowly re-elected in 1916, his second term centered on World War I. He tried to maintain U.S. neutrality, but when the German Empire began unrestricted submarine warfare, he wrote several admonishing notes to Germany, and in April 1917 asked Congress to declare war on the Central Powers. He focused on diplomacy and financial considerations, leaving the waging of the war primarily in the hands of the military establishment. On the home front, he began the first effective draft in 1917, raised billions in war funding through Liberty Bonds, imposed an income tax, enacted the first federal drug prohibition, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union growth, supervised agriculture and food production through the Lever Act, took over control of the railroads, and suppressed anti-war movements. He paid surprisingly little attention to military affairs, but provided the funding and food supplies that helped the Americans in the war and hastened Allied victory in 1918. National women's suffrage and democratic election of the Senate were achieved under Wilson's presidency, although his largely progressive term was tempered by conservative and sometimes regressive policies towards racial equality.

In the late stages of the war, Wilson took personal control of negotiations with Germany, including the armistice. He issued his Fourteen Points, his view of a post-war world that could avoid another terrible conflict. He went to Paris in 1919 to create the League of Nations and shape the Treaty of Versailles, with special attention on creating new nations out of defunct empires. Largely for his efforts to form the League, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919. Wilson collapsed with a debilitating stroke in 1919, as the home front saw massive strikes and race riots, and wartime prosperity turn into postwar depression. He refused to compromise with the Republicans who controlled Congress after 1918, effectively destroying any chance for ratification of the Versailles Treaty. The League of Nations was established anyway, but the United States never joined. Wilson's idealistic internationalism, calling for the United States to enter the world arena to fight for democracy, progressiveness, and liberalism, has been a highly controversial position in American foreign policy, serving as a model for "idealists" to emulate or "realists" to reject for the following century. Wilson has been ranked by some scholars as one of the greatest U.S. Presidents.

Early life

Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia in 1856 as the third of four children of Reverend Dr. Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888).[1] His ancestry was Scots-Irish and Scottish. His paternal grandparents immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland in 1807, while his mother was born in Carlisle to Scottish parents. His grandparents' whitewashed house still stands, and has become a tourist attraction in Northern Ireland. Descendants of the Wilsons still live in the farmhouse next door to it.[4]

Wilson's father was originally from Steubenville, Ohio where his grandfather had been an abolitionist newspaper publisher and his uncles were Republicans. Wilson's parents moved South in 1851 and identified with the Confederacy. His father defended slavery, owned slaves and set up a Sunday school for them. They cared for wounded soldiers at their church. The father also briefly served as a chaplain to the Confederate Army.[5] Woodrow Wilson's earliest memory, from the age of three, was of hearing that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming. Wilson would forever recall standing for a moment at Robert E. Lee's side and looking up into his face.[5]

Wilson’s father was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) after it split from the northern Presbyterians in 1861. Joseph R. Wilson served as the first permanent clerk of the southern church’s General Assembly, was Stated Clerk from 1865-1898 and was Moderator of the PCUS General Assembly in 1879. Wilson spent the majority of his childhood, up to age 14, in Augusta, Georgia, where his father was minister of the First Presbyterian Church.[6]

Wilson did not learn to read until he was about 12 years old. His difficulty reading may have indicated dyslexia or A.D.H.D., but as a teenager he taught himself shorthand to compensate and was able to achieve academically through determination and self-discipline. He studied at home under his father's guidance and took classes in a small school in Augusta.[7] During Reconstruction, he lived in Columbia, South Carolina, the state capital, from 1870-1874, where his father was professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary.[8]

In 1873, he spent a year at Davidson College in North Carolina, then transferred to Princeton as a freshman, graduating in 1879, becoming a member of Phi Kappa Psi fraternity. Beginning in his second year, he read widely in political philosophy and history. Wilson credited the British parliamentary sketch-writer Henry Lucy as his inspiration in resolving to enter public life. He was active in the undergraduate American Whig-Cliosophic Society discussion club, and organized a separate Liberal Debating Society.[9]

In 1879, Wilson attended law school at University of Virginia for one year. Although he never graduated, during his time at the University he was heavily involved in the Virginia Glee Club and the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society, serving as the Society's president.[10] His frail health dictated withdrawal, and he went home to Wilmington, North Carolina where he continued his studies.

He entered graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University in 1883 and three years later received a Ph.D. in political science. After completing his doctoral dissertation, Congressional Government, in 1885, he received academic appointments at Bryn Mawr College (1885-88) and Wesleyan University (1888-90).[11]

Personal life

Health

Wilson’s mother was possibly a hypochondriac. Consequently, Wilson seemed to think that he was often in poorer health than he really was. However, he did suffer from hypertension at a relatively early age and may have suffered his first stroke at age 39.[12]

Family

In 1885, he married Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a minister from Rome, Georgia. They had three daughters: Margaret Woodrow Wilson (1886-1944); Jessie Wilson (1887-1933); and Eleanor R. Wilson (1889-1967)[1] He remarried in 1915 after Axson died. Wilson is the last President to become a widower while still in office.

Hobbies

Wilson was an early automobile enthusiast, and he took daily rides while he was President. His favorite car was a 1919 Pierce-Arrow, in which he preferred to ride with the top down.[13] His enjoyment of motoring made him an advocate of funding for public highways.[14]

Wilson was an avid baseball fan. In 1916, he became the first sitting president to attend a World Series game. Wilson had been a center fielder during his Davidson College days. When he transferred to Princeton he was unable to make the varsity and so became the assistant manager of the team. He was the first President officially to throw out a first ball at a World Series.[15]

He cycled regularly, including several cycling vacations in the Lake District in Britain. Unable to cycle around Washington, D.C. as President, Wilson took to playing golf, although he played with more enthusiasm than skill. Wilson holds the record of all the presidents for the most rounds of golf, over 1,000, or almost one every other day. During the winter, the Secret Service would paint golf balls with black paint so Wilson could hit them around in the snow on the White House lawn.[16]

Public life

Legal career

In January 1882, Wilson decided to start his first law practice in Atlanta. One of Wilson’s University of Virginia classmates, Edward Ireland Renick, invited Wilson to join his new law practice as partner. Wilson joined him there in May 1882. He passed the Georgia Bar. On October 19, 1882, he appeared in court before Judge George Hillyer to take his examination for the bar, which he passed with flying colors and he began work on his thesis Congressional Government in the United States.[17] Competition was fierce in the city with 143 other lawyers, so with few cases to keep him occupied, Wilson quickly grew disillusioned.

Moreover, Wilson had studied law in order to eventually enter politics, but he discovered that he could not continue his study of government and simultaneously continue the reading of law necessary to stay proficient. In April 1883, Wilson applied to the new Johns Hopkins University to study for a Ph.D. in history and political science, which he completed in 1886.[18]

Wilson would later serve as president of the American Political Science Association in 1910, and remains the only U.S. president to have earned a Ph. D., and the only political scientist to become president. In July 1883, Wilson left his law practice to begin his academic studies.[19]

Political writings

Wilson came of age in the decades after the American Civil War, when Congress was supreme— "the gist of all policy is decided by the legislature" —and corruption was rampant. Instead of focusing on individuals in explaining where American politics went wrong, Wilson focused on the American constitutional structure.[20]

Under the influence of Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution, Wilson saw the United States Constitution as pre-modern, cumbersome, and open to corruption. An admirer of Parliament (though he did not visit Great Britain until 1919), Wilson favored a parliamentary system for the United States. Writing in the early 1880s:

- "I ask you to put this question to yourselves, should we not draw the Executive and Legislature closer together? Should we not, on the one hand, give the individual leaders of opinion in Congress a better chance to have an intimate party in determining who should be president, and the president, on the other hand, a better chance to approve himself a statesman, and his advisers capable men of affairs, in the guidance of Congress?"[21]

Wilson's article The Study of Administration was published in June of 1887 within the Political Science Quarterly. Wilson believed that public administration was an important topic not just because of growing popularity within college campuses. He believed it was a requirement for a growing nation. He defined public administration simply as “government in action; it is the executive, the operative, the most visible side of government, and is of course as old as government itself” (Wilson 3). He believed that by studying public administration that governmental efficiency may be increased.

This set the tone for his following discussion. Wilson was concerned with the implementation of government and not just its principles defined by documents such as the Constitution. Wilson analyzed European history and saw a pattern where educated leaders debated the nature of the state, yet the question of how should the law be administrated was relegated to a lowly “practical detail”. Most of this was due to a much smaller—in comparison to the 19th century—population with the government being relatively “simple”.

Wilson thought it was long past due time to confront these issues, or as he put the problem, “[i]t is getting to be harder to run a constitution than to frame one” (Wilson 4). His justification and purpose for a science of administration was for it to “seek to straighten the paths of government, to make its business less unbusinesslike, to strengthen and purify its organization, and it to crown its dutifulness” (Wilson 5).

The first problem (as he saw it) identified was that so far the advancement of this science had been undertaken by Europeans, not including England, whose goals and historical backgrounds were far different from America. He declared that Americans must advance this science as well, to steep it in the American tradition and make this science their own.

Wilson then described the growth of modern governments, starting with absolute rule, progressing to popular rule based upon a constitution, and then finally leading to a stage where the people undertake to develop administration as a science. He briefly gives an overview of the growth of such foreign states as Prussia, France, and England, highlighting the events that led to advances in administration.

The next problem was that the American Republic required great compromise since public opinion differed on so many levels. The people of America itself come from diverse backgrounds. These people must be convinced to form a majority opinion. Thus practical reform to the government is necessarily slow. Although this could be judged a good thing since a single person cannot make drastic, damaging changes. Every change must be pondered at length.

Now Wilson insisted that “administration lies outside the proper sphere of politics” (Wilson 10) and that “general laws which direct these things to be done are as obviously outside of and above administration” (Wilson 11). He likens administration to a machine that functions independent of the changing mood of its leaders.

Such a line of demarcation is intended to focus responsibility for actions taken on the people or persons in charge. As Wilson put it, “[p]ublic attention must be easily directed, in each case of good or bad administration, to just the man deserving of praise or blame. There is no danger in power, if only it be not irresponsible. If it be divided, dealt out in share to many [presumably within administration], it is obscured...” (Wilson 12). Essentially, the items under the discretion of administration must be limited in scope, as to not block, nullify, obfuscate, or modify the implementation of governmental decree made by the executive branch. While this is Wilson’s ideal in today’s practice people within administration often greatly influence the makeup of law and not just its implementation.

'Congressional Government'

Wilson started Congressional Government, his best known political work, as an argument for a parliamentary system, but Wilson was impressed by Grover Cleveland, and Congressional Government emerged as a critical description of America's system, with frequent negative comparisons to Westminster. Wilson himself claimed, "I am pointing out facts—diagnosing, not prescribing remedies.".[22]

Wilson believed that America's intricate system of checks and balances was the cause of the problems in American governance. He said that the divided power made it impossible for voters to see who was accountable for ill-doing. If government behaved badly, Wilson asked,

- "...how is the schoolmaster, the nation, to know which boy needs the whipping? ... Power and strict accountability for its use are the essential constituents of good government.... It is, therefore, manifestly a radical defect in our federal system that it parcels out power and confuses responsibility as it does. The main purpose of the Convention of 1787 seems to have been to accomplish this grievous mistake. The 'literary theory' of checks and balances is simply a consistent account of what our Constitution makers tried to do; and those checks and balances have proved mischievous just to the extent which they have succeeded in establishing themselves... [the Framers] would be the first to admit that the only fruit of dividing power had been to make it irresponsible."[23]

The longest section of Congressional Government is on the United States House of Representatives, where Wilson pours out scorn for the committee system. Power, Wilson wrote,

- "is divided up, as it were, into forty-seven seignories, in each of which a Standing Committee is the court-baron and its chairman lord-proprietor. These petty barons, some of them not a little powerful, but none of them within reach [of] the full powers of rule, may at will exercise an almost despotic sway within their own shires, and may sometimes threaten to convulse even the realm itself".[24]

Wilson said that the committee system was fundamentally undemocratic because committee chairs, who ruled by seniority, were responsible to no one except their constituents, even though they determined national policy.

In addition to its undemocratic nature, Wilson also believed that the Congressional Committee System facilitated corruption.

- "the voter, moreover, feels that his want of confidence in Congress is justified by what he hears of the power of corrupt lobbyists to turn legislation to their own uses. He hears of enormous subsidies begged and obtained... of appropriations made in the interest of dishonest contractors; he is not altogether unwarranted in the conclusion that these are evils inherent in the very nature of Congress; there can be no doubt that the power of the lobbyist consists in great part, if not altogether, in the facility afforded him by the Committee system.[25]

By the time Wilson finished Congressional Government, Grover Cleveland was President, and Wilson had his faith in the United States government restored. When William Jennings Bryan captured the Democratic nomination from Cleveland's supporters in 1896, however, Wilson refused to stand by the ticket. Instead, he cast his ballot for John M. Palmer, the presidential candidate of the National Democratic Party, or Gold Democrats, a short-lived party that supported a gold standard, low tariffs, and limited government.[26]

After experiencing the vigorous presidencies of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, Wilson no longer entertained thoughts of parliamentary government at home. In his last scholarly work in 1908, Constitutional Government of the United States, Wilson said that the presidency "will be as big as and as influential as the man who occupies it". By the time of his presidency, Wilson merely hoped that Presidents could be party leaders in the same way prime ministers were. Wilson also hoped that the parties could be reorganized along ideological, not geographic, lines. "Eight words," Wilson wrote, "contain the sum of the present degradation of our political parties: No leaders, no principles; no principles, no parties."[27]

Academic career

Wilson served on the faculties of Bryn Mawr College and Wesleyan University. At Wesleyan, he also coached the football team and founded the debate team - to this date, it is named the T. Woodrow Wilson debate team. He then joined the Princeton faculty as professor of jurisprudence and political economy in 1890. While there, he was one of the faculty members of the short-lived coordinate college, Evelyn College for Women. Additionally, Wilson became the first lecturer of Constitutional Law at New York Law School where he taught with Charles Evans Hughes.

Wilson delivered an oration at Princeton's sesquicentennial celebration (1896) entitled "Princeton in the Nation's Service." (This has become a frequently alluded-to motto of the University, later expanded to "Princeton in the Nation's Service and in the Service of All Nations."[28]) In this famous speech, he outlined his vision of the university in a democratic nation, calling on institutions of higher learning "to illuminate duty by every lesson that can be drawn out of the past".

The trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president of Princeton in 1902. Although the school's endowment was barely $4 million, he sought $2 million for a preceptorial system of teaching, $1 million for a school of science, and nearly $3 million for new buildings and salary raises. As a long-term objective, Wilson sought $3 million for a graduate school and $2.5 million for schools of jurisprudence and electrical engineering, as well as a museum of natural history.

He achieved little of that because he was not a strong fund raiser, but he did increase the faculty from 112 to 174, most of them personally selected as outstanding teachers. The curriculum guidelines he developed proved important progressive innovations in the field of higher education.

To enhance the role of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements where students met in groups of six with preceptors, followed by two years of concentration in a selected major. He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman C" with serious study. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men."

In 1906-10, he attempted to curtail the influence of the elitist "social clubs" by abolishing the upperclass eating clubs and moving the students into colleges, also known as "quadrangles." Wilson's "Quad Plan" was met with fierce opposition from Princeton's alumni, most importantly Moses Taylor Pyne, the most powerful of Princeton's Trustees. Wilson refused any proposed compromises that stopped short of abolishing the clubs because he felt that to compromise "would be to temporize with evil."[29] In October 1907, due to the ferocity of alumni opposition and Wilson's refusal to compromise, the Board of Trustees took back its initial support for the Quad Plan and instructed Wilson to withdraw it.[30]

Even more damaging was his confrontation with Andrew Fleming West, Dean of the graduate school, and West's ally, former President Grover Cleveland, a trustee. Wilson wanted to integrate the proposed graduate building into the same area with the undergraduate colleges; West wanted them separated. The trustees rejected Wilson's plan for colleges in 1908, and then endorsed West's plans in 1909. The national press covered the confrontation as a battle of the elites (West) versus democracy (Wilson). During this time in his personal life, Wilson engaged in an extramarital affair with socialite Mary Peck.[31] Wilson, after considering resignation, decided to take up invitations to move into New Jersey state politics.[32]

Governor of New Jersey

In 1910 Wilson ran for Governor of New Jersey against the Republican candidate Vivian M. Lewis, the State Commissioner of Banking and Insurance. Wilson's campaign focused on his independence from machine politics, and he promised that if elected he would not be beholden to party bosses. Wilson soundly defeated Lewis in the general election by a margin of more than 49,000 votes, despite the fact that Republican William Howard Taft had carried New Jersey in the 1908 presidential election by more than 80,000 votes.[33]

In the 1910 election the Democrats also took control of the General Assembly. The State Senate, however, remained in Republican control by a slim margin. After taking office, Wilson set in place his reformist agenda, ignoring the demands of party machinery. While governor, in a period spanning six months, Wilson established state primaries. This all but took the party bosses out of the presidential election process in the state. He also revamped the public utility commission, and introduced worker's compensation.[34]

Presidency 1913-1921

First term

Wilson defeated two former U.S. presidents, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, to win the election of 1912.

Wilson experienced early success by implementing his "New Freedom" pledges of antitrust modification, tariff revision, and reform in banking and currency matters. He held the first modern presidential press conference, on March 15, 1913, in which reporters were allowed to ask him questions.[35] He would later become more disillusioned with the press, as he fought to establish the League of Nations.[35]

Wilson's first wife Ellen died on August 6, 1914 of Bright's disease. In 1915, he met Edith Galt. They married later that year on December 18. Wilson arrived at the White House with severe digestive problems. He treated himself with a stomach pump.[36]

Wilson, born in Virginia and raised in Georgia, was the first Southerner to be elected President since Zachary Taylor in 1848 and the first Southerner to take office since Andrew Johnson in 1865, as well as the first President to deliver his State of the Union address before Congress personally since John Adams in 1799. Wilson was also the first Democrat elected to the presidency since Grover Cleveland in 1892. The next Democrat elected was Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932.

Federal Reserve 1913

Wilson secured passage of the Federal Reserve system in late 1913 in exchange for campaign support. He took a plan that had been designed by conservative Republicans—led by Nelson W. Aldrich and banker Paul M. Warburg, along with Wilson's close adviser Col. Edward House, at Jekyll Island—and pressured an initially reluctant Congress to pass it.[37][38] Wilson had to find a middle ground between those who supported the Aldrich Plan and those who opposed it, including the powerful agrarian wing of the party, led by William Jennings Bryan, which strenuously denounced private banks and Wall Street.[39][40]

They wanted a government-owned central bank which could print paper money whenever Congress wanted.[40] Wilson’s alternate plan allowed the large banks to have important influence, but Wilson went beyond the Aldrich Plan and created a central board made up of persons appointed by the President and approved by Congress who would outnumber the board members who were bankers at that time.

Moreover, Wilson convinced Bryan’s supporters that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government, the plan fit their demands. Wilson’s plan also organized the Federal Reserve system into 12 districts. This was designed to weaken the influence of the powerful New York banks, a key demand of Bryan’s allies in the Southern United States and Western United States. This decentralization was a key factor in winning the support of Congressman Carter Glass (D-VA), although he objected to making paper currency a federal obligation; he sponsored and wrote the legislation, and his home state capitol of Richmond, Virginia received a Reserve headquarters.[38] Wilson also mollified the bill's opponents by saying that he would pursue antitrust legislation in return for their vote.[40]

Glass was one of the leaders of the currency reformers in the U.S. House and without his support, any plan was doomed to fail. The final plan passed, in December 1913, two days before Christmas when most of Congress was on vacation. Some bankers felt it gave too much control to Washington, and some reformers felt it allowed bankers to maintain too much power. However, several Congressmen claimed that the New York bankers feigned their disapproval of the bill in hopes of inducing Congress to pass it. The day before the bill was passed, Rep. Victor Murdock told Congress:

"You allowed the special interests by pretended dissatisfaction with the measure to bring about a sham battle, and the sham battle was for the purpose of diverting you people from the real remedy, and they diverted you. The Wall Street bluff has worked."[41]

Wilson named Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system. While the power was supposed to be decentralized, the New York branch has dominated the Fed as the "first among equals" and thus power has somewhat remained in Wall Street.[42] The new system began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war efforts.[43] Wilson appeared on the $100,000 bill. The bill, which is now out of print but is still legal tender, was used only to transfer money between Federal Reserve banks.[44][45]

Wilsonian economic views

Wilson's early views on international affairs and trade were stated in his Columbia University lectures of April 1907 where he said:

- "Since trade ignores national boundaries and the manufacturer insists on having the world as a market, the flag of his nation must follow him, and the doors of the nations which are closed must be battered down…Concessions obtained by financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations be outraged in the process. Colonies must be obtained or planted, in order that no useful corner of the world may be overlooked or left unused".[46]

Other economic policies

In 1913, the Underwood tariff lowered the tariff. The revenue thereby lost was replaced by a new federal income tax (authorized by the 16th Amendment, which had been sponsored by the Republicans). The "Seaman's Act" of 1915 improved working conditions for merchant sailors. As response to the RMS Titanic disaster, it also required all ships to be retrofitted with lifeboats.

A series of programs were targeted at farmers. The "Smith Lever" act of 1914 created the modern system of agricultural extension agents sponsored by the state agricultural colleges. The agents taught new techniques to farmers. The 1916 "Federal Farm Loan Board" issued low-cost long-term mortgages to farmers.[47]

Child labor was curtailed by the Keating-Owen Act of 1916, but the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1918.[48][49]Additional child labor bills would not be enacted until the 1930s.

The railroad brotherhoods threatened in summer 1916 to shut down the national transportation system. Wilson tried to bring labor and management together, but when management refused he had Congress pass the "Adamson Act" in September 1916, which avoided the strike by imposing an 8-hour work day in the industry (at the same pay as before). It helped Wilson gain union support for his reelection; the act was approved by the Supreme Court.

Antitrust

Wilson broke with the "big-lawsuit" tradition of his predecessors Taft and Roosevelt as "Trustbusters", finding a new approach to encouraging competition through the Federal Trade Commission, which stopped "unfair" trade practices. In addition, he pushed through Congress the Clayton Antitrust Act making certain business practices illegal (such as price discrimination, agreements forbidding retailers from handling other companies’ products, and directorates and agreements to control other companies). The power of this legislation was greater than previous anti-trust laws, because individual officers of corporations could be held responsible if their companies violated the laws. More importantly, the new laws set out clear guidelines that corporations could follow, a dramatic improvement over the previous uncertainties. This law was considered the "Magna Carta" of labor by Samuel Gompers because it ended union liability antitrust laws. In 1916, under threat of a national railroad strike, he approved legislation that increased wages and cut working hours of railroad employees; there was no strike.

War policy—World War I

Wilson spent 1914 through the beginning of 1917 trying to keep America out of the war in Europe. He offered to be a mediator, but neither the Allies nor the Central Powers took his requests seriously. Republicans, led by Theodore Roosevelt, strongly criticized Wilson’s refusal to build up the U.S. Army in anticipation of the threat of war. Wilson won the support of the U.S. peace element by arguing that an army buildup would provoke war. However for all his words, Wilson was anything but neutral. His pro-British views caused his Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan to resign in protest in 1915.

While German submarines were sinking merchant ships, the U.S. and Wilson stayed neutral. Britain had declared a blockade of Germany, preventing neutral shipping carrying “contraband” goods to Germany. Wilson protested this violation of neutral rights by London, but his protests were mild, and the British knew America would not take action.

Segregation in the federal government

In 1912 "An unprecedented number"[50]of African Americans had left the Republicans to cast their vote for the Democrat Wilson, encouraged by his promises of support for their issues. They were disappointed when early in his administration he allowed the introduction of segregation into several federal departments, and failed to veto a law making miscegenation a felony in the District of Columbia. The issue of segregation came up early in his presidency when at an April 1913 cabinet meeting, Albert Burleson, his Postmaster General and a southern native, complained about working conditions at the Railway Mail Service. Offices and restrooms became segregated, sometimes by partitions erected between seating for white and African-American employees in Post Office Department offices, lunch rooms, and bathrooms, as well as in the Treasury and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. It also became accepted policy that 'Negro' employees of the Postal Service could have their rank reduced or be dismissed. And unlike his predecessors Grover Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt, Wilson backed down in the face of Southern opposition to the re-appointment of an African-American to the position of Register of the Treasury, and other positions within the federal government. This set the tone for Wilson's attitude to race throughout his presidency, in which the rights of African-Americans were sacrificed in the short term, for what he felt would be the more important longer term progress of the common good.[51][52]

Election of 1916

Renominated in 1916, Wilson's major campaign slogan was "He kept us out of the war", referring to his administration's avoiding open conflict with Germany or Mexico while maintaining a firm national policy. Wilson, however, never promised to keep out of war regardless of provocation. In his acceptance speech on September 2, 1916, Wilson pointedly warned Germany that submarine warfare that took American lives would not be tolerated:

- "The nation that violates these essential rights must expect to be checked and called to account by direct challenge and resistance. It at once makes the quarrel in part our own."[53]

Wilson narrowly won the election, defeating Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes. As governor of New York from 1907-1910, Hughes had a progressive record, strikingly similar to Wilson's as governor of New Jersey. Theodore Roosevelt would comment that the only thing different between Hughes and Wilson was a shave. However, Hughes had to try to hold together a coalition of conservative Taft supporters and progressive Roosevelt partisans and so his campaign never seemed to take a definite form. Wilson ran on his record and ignored Hughes, reserving his attacks for Roosevelt. When asked why he did not attack Hughes directly, Wilson told a friend to “Never murder a man who is committing suicide.”[54]

The final result was exceptionally close and the result was in doubt for several days. Because of Wilson's fear of becoming a lame duck president during the uncertainties of the war in Europe, he created a hypothetical plan where if Hughes were elected he would name Hughes secretary of state and then resign along with the vice-president to enable Hughes to become the president. The vote came down to several close states. Wilson won California by 3,773 votes out of almost a million votes cast and New Hampshire by 54 votes. Hughes won Minnesota by 393 votes out of over 358,000. In the final count, Wilson had 277 electoral votes vs. Hughes 254. Wilson was able to win reelection in 1916 by picking up many votes that had gone to Teddy Roosevelt or Eugene V. Debs in 1912.

Second term

Decision for War, 1917

Before entering the war in 1917, the U.S. had made a declaration of neutrality in 1914. During this time of neutrality, President Wilson warned citizens not to take sides in the war in fear of endangering wider U.S. policy. In his address to congress in 1914, Wilson states, “Such divisions amongst us would be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation, not as a partisan, but as a friend.” [55] Woodrow Wilson did not hold his strict belief, that America could achieve peace without victory, for long.

The U.S. neutrality would deteriorate when Germany began to initiate its unrestricted submarine warfare threatening U.S. commercial shipping. When Germany started unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 and made an attempt to enlist Mexico as an ally (see Zimmermann Telegram), Wilson took America into World War I as a war to make "the world safe for democracy." He did not sign a formal alliance with the United Kingdom or France but operated as an "Associated" power. He raised a massive army through conscription and gave command to General John J. Pershing, allowing Pershing a free hand as to tactics, strategy and even diplomacy.

Woodrow Wilson had decided by then that the war had become a real threat to humanity. Unless the U.S. threw its weight into the war, as he stated in his declaration of war speech, on April 2nd, 1917.[56] Western civilization itself could be destroyed. His statement announcing a "war to end all wars" meant that he wanted to build a basis for peace that would prevent future catastrophic wars and needless death and destruction. This provided the basis of Wilson's Fourteen Points, which were intended to resolve territorial disputes, ensure free trade and commerce, and establish a peacemaking organization, which later emerged as the League of Nations.

To stop defeatism at home, Wilson pushed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 through Congress to suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war opinions. He welcomed socialists who supported the war, such as Walter Lippmann, but would not tolerate those who tried to impede the war or, worse, assassinate government officials, and pushed for deportation of foreign-born radicals.[57] Over 170,000 US citizens were arrested during this period, in some cases for things they said about the president in their own homes. Citing the Espionage Act, the U.S. Post Office refused to carry any written materials that could be deemed critical of the U. S. war effort. Some sixty newspapers were deprived of their second-class mailing rights.

His wartime policies were strongly pro-labor, though again, he had no love for radical unions like the Industrial Workers of the World. The American Federation of Labor and other 'moderate' unions saw enormous growth in membership and wages during Wilson's administration. There was no rationing, so consumer prices soared. As income taxes increased, white-collar workers suffered. Appeals to buy war bonds were highly successful, however. Bonds had the result of shifting the cost of the war to the affluent 1920s.

Wilson set up the first western propaganda office, the United States Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel (thus its popular name, Creel Commission), which filled the country with patriotic anti-German appeals and conducted various forms of censorship.[58] In 1917, Congress authorized ex-President Theodore Roosevelt to raise four divisions of volunteers to fight in France- Roosevelt's World War I volunteers; Wilson refused to accept this offer.

War Message

Woodrow Wilson's War Message was delivered on April 2, 1917. This day he had stood up before Congress and delivered his historic speech. [59]

April 2nd was a cold and rainy day in Washington D.C. and thousands of supporters gathered to support President Wilson. Wilson had slept very little the night before but still spent the day reading over his address with Colonel House, a close friend, as they reworded and corrected the speech. That evening Wilson made his way to the State, War and Navy Building to discuss the war proclamation. At approximately 8:30 p.m. President Wilson was introduced to Congress. He walked to the rostrum and arranged his papers of his speech in a particular order on the podium. The applause that he received was the greatest that President Wilson had ever received in front of Congress. He waited impatiently for the applause to die down before he started his address. He had an intense look on his face and remained intense and almost motionless for the entire speech, only raising one arm as his only bodily movement.[60]

In President Wilson’s war message presented to Congress, he addressed a few main points to Congress about why the United States was required to enter the war. He first brought to their attention that the Imperial German Government had announced that it would begin using its submarines to sink any vessel approaching the ports of Great Britain, Ireland or any of the Western Coasts of Europe. Wilson’s main concern was not that ships or any type of property were being damaged, but that innocent lives were being taken in these attacks by the Germans. Wilson announced that even though his previous thought was to remain in an “armed neutrality” state, it had become evident that this was no longer a practical tactic. He advised Congress to declare that the recent course of action taken by the Imperial German Government to be nothing less than war.

Wilson continues on to state that the object of this war was to “vindicate principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power…” He also describes the other undermining attacks on the U.S. by the German government by pointing out that they had “filled our unsuspecting communities and even our offices of government with spies and set criminal intrigues everywhere afoot against our national unity of counsel, our peace within and without our industries and our commerce.” The United States had also intercepted a telegram sent to the German ambassador in Mexico City which provided evidence that Germany meant to convince Mexico to attack the U.S., hence Wilson states that the German government “means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors.”

Wilson ends his address to Congress with the statement that the world must be once again safe for democracy.[61]

Once he ended his War message in front of the joint houses of congress, the place loudly roared in applause. Wilson’s speech was not just for Congress but for the American public.

Of the thousands of supporters in Washington that day “Hundreds carried little American flags. The very atmosphere was explosive with excitement.” Going into the speech, there were those in support and those opposed to entering the war, but afterwards the support for Wilson was unanimous. According to a speech made by Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. of Wisconsin, many were opposed to the war. In the three to four days that Congress had to decide whether to declare war or not, several telegrams and petitions were wired to him in Washington expressing disagreement with going to war. Senator Robert La Follette was one of only six senators that had opposed Wilson’s decision to go to war. Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska was also an Irreconcilable because he too was opposed to entry into WWI.

George W. Norris stated “I am most emphatically and sincerely opposed to taking any step that will force our country into the useless and senseless war now being waged in Europe…” He provided reasonable examples of how the United States is unfair in declaring war on Germany. One of his examples was that the British had declared a war zone on November 4th and America had submitted to it, but when Germany declared a war zone on February 4th America had opposed it. Both of them had violated international law and interfered with our neutral rights, and America only acts against Germany and not both. Again, he finds evidence where there are “Many instances of cruelty and inhumanity (that) can be found on both sides”. Norris believed that the government only wanted to take part in this war because the wealthy had already aided British financially in the war. He told Congress that the only people who would benefit from the war were “munition manufacturers, stockbrokers, and bond dealers”. He presented evidence to the Congress in the form of a letter written by a member of the New York Stock Exchange. He concluded from his evidence that “Here we have the man representing the class of people who will be made prosperous should we become entangled in the present war, who have already made millions of dollars, and who will make many hundreds of millions more if we get into the war”. George W. Norris’s concludes that it is not worth going to war just to benefit the rich and to “deliver munitions of war to belligerent nations”. “War brings no prosperity to the great mass of common and patriotic citizens. It increases the cost of living of those who toil and those who already must strain every effort to keep soul and body together. War brings prosperity to the stock gambler on Wall Street--to those who are already in possession of more wealth than can be realized or enjoyed”. [8] [62]

Robert M. La Follette’s main argument too relates to Norris’ arguments. He also believed though, that once we entered WWI, our reputation of America would deteriorate; “When we cooperate with those governments, we endorse their methods; we endorse the violations of international law by Great Britain; we endorse the shameful methods of warfare against which we have again and again protested in this war”. He also gave recognition to Woodrow Wilson’s speech and how Wilson aimed towards his audience’s feelings. He criticized Wilson that “In many places throughout the address is this exalted sentiment given expression. It is a sentiment peculiarly calculated to appeal to American hearts and, when accompanied by acts consistent with it, is certain to receive our support”. [63]

Despite what Norris and La Follette had to say, Congress had made a declaration of war on April 4th, 1917.

American Protective League

The American Protective League was a quasi-private organization with 250,000 members in 600 cities was sanctioned by the Wilson administration. These men carried Government Issue badges and freely conducted warrantless searches and interrogations.[64] This organization was empowered by the U.S. Justice Department to spy on Americans for anti-government/anti war behavior. As national police, the APL checked up on people who failed to buy Liberty Bonds and spoke out against the government’s policies.

The Fourteen Points

President Woodrow Wilson articulated what became known as the Fourteen Points before Congress on January 8, 1918. The Points were the only war aims clearly expressed by any belligerent nation and thus became the basis for the Treaty of Versailles following World War I. The speech was highly idealistic, translating Wilson's progressive domestic policy of democracy, self-determination, open agreements, and free trade into the international realm. It also made several suggestions for specific disputes in Europe and the Middle East on the recommendation of Wilson's foreign policy adviser, Colonel Edward M. House, and his team of 150 advisers known as “The Inquiry.” The points were:

- Abolition of secret treaties

- Freedom of the seas

- Free Trade

- Disarmament

- Adjustment of colonial claims (decolonization and national self-determination)

- Russia to be assured independent development and international withdrawal from occupied Russian territory

- Restoration of Belgium to antebellum national status

- Alsace-Lorraine returned to France from Germany

- Italian borders redrawn on lines of nationality

- Autonomous development of Austria-Hungary as a nation, as the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved

- Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, and other Balkan states to be granted integrity, have their territories de-occupied, and Serbia to be given access to the Adriatic Sea

- Sovereignty for the Turkish people of the Ottoman Empire as the Empire dissolved, autonomous development for other nationalities within the former Empire

- Establishment of an independent Poland with access to the sea

- General association of the nations – a multilateral international association of nations to enforce the peace (League of Nations)[65]

The speech was controversial in America, and even more so with its Allies. France wanted high reparations from Germany as French agriculture, industry, and lives had been so demolished by the war; and Britain, as the great naval power, did not want freedom of the seas. Wilson compromised with Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and many other European leaders during the Paris Peace talks to ensure that the fourteenth point, the League of Nations, would be established. In the end, Wilson's own Congress did not accept the League and only four of the original Fourteen Points were implemented fully in Europe.

Other foreign affairs

Between 1914 and 1918, the United States intervened in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, and Panama. The U.S. maintained troops in Nicaragua throughout his administration and used them to select the president of Nicaragua and then to force Nicaragua to pass the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty. American troops in Haiti forced the Haitian legislature to choose the candidate Wilson selected as Haitian president. American troops occupied Haiti between 1915 and 1934.

After Russia left the war in 1917 following the Bolshevik Revolution, the Allies sent troops there, presumably, to prevent a German or Bolshevik takeover of allied-provided weapons, munitions and other supplies, which had been previously shipped as aid to the Czarist government. Wilson sent armed forces to assist the withdrawal of Czech and Slovak prisoners along the Trans-Siberian Railway, hold key port cities at Arkangel and Vladivostok, and safeguard supplies sent to the Tsarist forces. Though not sent to engage the Bolsheviks, the U.S. forces had several armed conflicts against forces of the new Russian government. Wilson withdrew most of the soldiers on April 1, 1920, though some remained as late as 1922. As Davis and Trani conclude,

- "Wilson, Lansing, and Colby helped lay the foundations for the later Cold War and policy of containment. There was no military confrontation, armed standoff, or arms race. Yet, certain basics were there: suspicion, mutual misunderstandings, dislike, fear, ideological hostility, and diplomatic isolation....Each side was driven by ideology, by capitalism versus communism. Each country sought to reconstruct the world. When the world resisted, pressure could be used."[66]

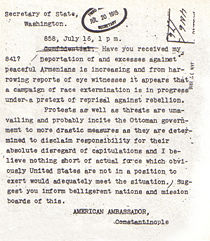

Armenian Genocide

In response to the circumstances of the Armenians at the time, Wilson went before Congress seeking a mandate of U.S. intervention in the form of humanitarian aid.

In 1913 Henry Morgenthau Sr., was appointed ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. In his capacity as ambassador, Morgenthau did his best to blunt the consequences of the Ottoman actions. A telegram detailing the "Armenian situation" was sent to Wilson, imparting the magnitude of the hardships faced by the Armenians. The full extent of the genocide was discussed in Morgenthau's book Ambassador Morgenthau's Story.[67] A book dedicated by the ambassador to Wilson.[67] Also, humanitarian aid was coordinated by the American Committee for Relief in the Near East, a society founded by Morgenthau.

Aftermath of World War I

Versailles 1919

After World War I, Wilson participated in negotiations with the stated aim of assuring statehood for formerly oppressed nations and an equitable peace. On January 8, 1918, Wilson made his famous Fourteen Points address, introducing the idea of a League of Nations, an organization with a stated goal of helping to preserve territorial integrity and political independence among large and small nations alike.

Wilson intended the Fourteen Points as a means toward ending the war and achieving an equitable peace for all the nations. He spent six months at Paris for the 1919 Paris Peace Conference (making him the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office). He worked tirelessly to promote his plan. The charter of the proposed League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles.

For his peace-making efforts, Wilson was hastily awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize,[68] however, he failed to even win US Senate support for ratification. The United States never joined the League. Republicans under Henry Cabot Lodge controlled the Senate after the 1918 elections, but Wilson refused to give them a voice at Paris and refused to agree to Lodge's proposed changes. The key point of disagreement was whether the League would diminish the power of Congress to declare war. During this period, Wilson became less trustful of the press and stopped holding press conferences for them, preferring to utilize his propaganda unit, the Committee for Public Information, instead.[35]

Historians generally have come to regard Wilson's failure to win U.S. entry into the League as perhaps the biggest mistake of his administration, and even as one of the largest failures of any American presidency.[69] The extensive restrictions in the Treaty of Versailles left the German populace with a resentment against the treaty and ultimately contributed to the rise of Adolf Hitler and World War II.

When Wilson traveled to Europe to settle the peace terms, Wilson visited Pope Benedict XV in Rome, which made Wilson the first American President to visit the Pope while in office.

Post war: 1919-20

Wilson had ignored the problems of demobilization after the war, and the process was chaotic and violent. Four million soldiers were sent home with little planning, little money, and few benefits. A wartime bubble in prices of farmland burst, leaving many farmers bankrupt or deeply in debt after they purchased new land. In 1919, major strikes in steel and meatpacking broke out.[70] Serious race riots hit Chicago, Omaha and other cities.

After a series of bombings by radical anarchist groups in New York and elsewhere, Wilson directed Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to put a stop to the violence. Palmer then ordered the Palmer Raids, with the aim of collecting evidence on violent radical groups, to deport foreign-born agitators, and jail domestic ones.[71]

Wilson broke with many of his closest political friends and allies in 1918-20, including Colonel House. Historians speculate that a series of strokes may have affected his personality. He desired a third term, but his Democratic party was in turmoil, with German voters outraged at their wartime harassment, and Irish voters angry at his failure to support Irish independence.

Eugenics

Wilson supported eugenics, and in 1907 he helped to make Indiana the first of more than thirty states to adopt legislation aimed at compulsory sterilization of certain individuals.[72] Although the law was overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1921,[73] the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the constitutionality of a Virginia law allowing for the compulsory sterilization of patients of state mental institutions in 1927.[74]

Incapacity

The cause of his incapacitation was the physical strain of the demanding public speaking tour he undertook to obtain support of the American people for ratification of the Covenant of the League. After one of his final speeches to attempt to promote the League of Nations in Pueblo, Colorado, on September 25, 1919[75] he collapsed. On October 2, 1919, Wilson suffered a serious stroke that almost totally incapacitated him, leaving him paralyzed on his left side and blind in his left eye. For at least a few months, he was confined to a wheelchair. Afterwards, he could walk only with the assistance of a cane. The full extent of his disability was kept from the public until after his death on February 3, 1924.

Wilson was purposely, with few exceptions, kept out of the presence of Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, his cabinet or Congressional visitors to the White House for the remainder of his presidential term. His first wife, Ellen, had died in 1914, so his second wife, Edith, served as his steward, selecting issues for his attention and delegating other issues to his cabinet heads. This was, as of 2008[update], the most serious case of presidential disability in American history and was later cited as a key example why ratification of the 25th Amendment was seen as important.

Administration and Cabinet

Wilson's chief of staff ("Secretary") was Joseph Patrick Tumulty 1913-1921, but he was largely upstaged after 1916 when Wilson's second wife, Edith Bolling Wilson, assumed full control of Wilson's schedule. An important foreign policy advisor and confidant was "Colonel" Edward M. House.

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Woodrow Wilson | 1913–1921 |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of State | William J. Bryan | 1913–1915 |

| Robert Lansing | 1915–1920 | |

| Bainbridge Colby | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William G. McAdoo | 1913–1918 |

| Carter Glass | 1918–1920 | |

| David F. Houston | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of War | Lindley M. Garrison | 1913–1916 |

| Newton D. Baker | 1916–1921 | |

| Attorney General | James C. McReynolds | 1913–1914 |

| Thomas W. Gregory | 1914–1919 | |

| A. Mitchell Palmer | 1919–1921 | |

| Postmaster General | Albert S. Burleson | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Josephus Daniels | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Franklin K. Lane | 1913–1920 |

| John B. Payne | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | David F. Houston | 1913–1920 |

| Edwin T. Meredith | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | William C. Redfield | 1913–1919 |

| Joshua W. Alexander | 1919–1921 | |

| Secretary of Labor | William B. Wilson | 1913–1921 |

Supreme Court appointments

Wilson appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- James Clark McReynolds – 1914

- Louis Dembitz Brandeis – 1916

- John Hessin Clarke – 1916

Wilsonian Idealism

Wilson was a remarkably effective writer and thinker. He composed speeches and other writings with two fingers on a little Hammond typewriter.[76] Wilson's diplomatic policies had a profound influence on shaping the world. Diplomatic historian Walter Russell Mead has explained:

- "Wilson's principles survived the eclipse of the Versailles system and that they still guide European politics today: self-determination, democratic government, collective security, international law, and a league of nations. Wilson may not have gotten everything he wanted at Versailles, and his treaty was never ratified by the Senate, but his vision and his diplomacy, for better or worse, set the tone for the twentieth century. France, Germany, Italy, and Britain may have sneered at Wilson, but every one of these powers today conducts its European policy along Wilsonian lines. What was once dismissed as visionary is now accepted as fundamental. This was no mean achievement, and no European statesman of the twentieth century has had as lasting, as benign, or as widespread an influence."[77]

American foreign relations since 1914 have rested on Wilsonian idealism, argues historian David Kennedy, even if adjusted somewhat by the "realism" represented by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Henry Kissinger. Kennedy argues that every president since Wilson has,

- "embraced the core precepts of Wilsonianism. Nixon himself hung Wilson's portrait in the White House Cabinet Room. Wilson's ideas continue to dominate American foreign policy in the twenty-first century. In the aftermath of 9/11 they have, if anything, taken on even greater vitality."[78]

Wilson and race

African Americans

While president of Princeton University, Wilson discouraged blacks from even applying for admission, preferring to keep the peace among white students than have black students admitted.[79] Princeton would not admit its first black student until the 1940s.

As President, Wilson allowed many of his cabinet officials to establish official segregation in most federal government offices, in some departments for the first time since 1863. "His administration imposed full racial segregation in Washington and hounded from office considerable numbers of black federal employees."[2] Wilson and his cabinet members fired many black Republican office holders in political appointee positions, but also appointed a few black Democrats to such posts. W. E. B. Du Bois, a leader of the NAACP, campaigned for Wilson and in 1918 was offered an Army commission in charge of dealing with race relations. (DuBois accepted, but he failed his Army physical and did not serve.)[80] When a delegation of blacks protested the discriminatory actions, Wilson told them that "segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen." In 1914, he told the New York Times, "If the colored people made a mistake in voting for me, they ought to correct it."

Wilson was highly criticized by African Americans for his actions. He was also criticized by southern hard-line racists such as Georgian Thomas E. Watson, who believed Wilson did not go far enough in restricting black employment in the federal government. The segregation introduced into the federal workforce by the Wilson administration was kept in place by the succeeding presidents and not officially ended until the Truman Administration.

Woodrow Wilson's History of the American People explained the Ku Klux Klan of the late 1860s as the natural outgrowth of Reconstruction, a lawless reaction to a lawless period. Wilson noted that the Klan "began to attempt by intimidation what they were not allowed to attempt by the ballot or by any ordered course of public action."[81] Although it is unclear whether Wilson's harsh critique of the Reconstruction was colored by his personal beliefs, it is clear that his critique provided much of the intellectual/historical justification for the racist policies/reactions of the 20th century American South.

In a 1923 letter to Senator Morris Sheppard of Texas, Wilson noted of the reborn Klan, "...no more obnoxious or harmful organization has ever shown itself in our affairs." Although Wilson had a volatile relationship with American blacks, he was a friend of the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, a black African monarch. A sword, a gift from Selassie, is on display at Wilson's Washington, DC house, now a museum.[82]

White ethnics

Wilson had harsh words to say about immigrants in his history books. But after he entered politics in 1910, Wilson worked to integrate immigrants into the Democratic party, into the army, and into American life. During the war, he demanded in return that they repudiate any loyalty to enemy nations.

Irish Americans were powerful in the Democratic party and opposed going to war as allies of their traditional enemy Great Britain, especially after the violent suppression of the Easter Rebellion of 1916. Wilson won them over in 1917 by promising to ask Great Britain to give Ireland its independence. At Versailles, however, he reneged and the Irish-American community vehemently denounced him. Wilson, in turn, blamed the Irish Americans and German Americans for lack of popular support for the League of Nations, saying,

- "There is an organized propaganda against the League of Nations and against the treaty proceeding from exactly the same sources that the organized propaganda proceeded from which threatened this country here and there with disloyalty, and I want to say, I cannot say too often, any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready."[83]

Wilson refused to meet with Éamon de Valera the President of Dáil Éireann during the latter's 1919 visit to the United States.

Mother's Day

In 1914, Wilson declared the first national Mother's Day[84]

- "Now, Therefore, I, Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the said Joint Resolution, do hereby direct the government officials to display the United States flag on all government buildings and do invite the people of the United States to display the flag at their homes or other suitable places on the second Sunday in May as a public expression of our love and reverence for the mothers of our country."

Death

In 1921, Wilson and his wife retired from the White House to a home in the Embassy Row section of Washington, D.C. Wilson continued going for daily drives and attended Keith's vaudeville theater on Saturday nights. Wilson was one of only two Presidents (Theodore Roosevelt was the first) who had been president of the American Historical Association.[85]

Wilson died in his S Street home on February 3, 1924. Because his plan for the League of Nations ultimately failed, he died feeling that he had lied to the American people and that his entry into the war had been in vain. He was buried in Washington National Cathedral, and is thus the only president buried in Washington, DC.[86]

Mrs. Wilson stayed in the home another 37 years, dying on December 28, 1961, ironically the same day she was to be the guest of honor at the opening of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge near Washington, D.C. She passed away with her favorite dog, Rooter, at her bedside. Mrs. Wilson left the home to the National Trust for Historic Preservation to be made into a museum honoring her husband. Woodrow Wilson House opened as a museum. It is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

Media

See also

- United States presidential election, 1912

- United States presidential election, 1916

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- History of the United States (1918–1945)

- World War I

- Racial equality proposal

- Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library

- The Woodrow Wilson House (Washington, D.C.)

- The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

- Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton, New Jersey

- USS Woodrow Wilson (SSBN-624)

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Woodrow (Thomas) Wilson". Geneology@jrac.com.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Foner, Eric. "Expert Report Of Eric Foner". The Compelling Need for Diversity in Higher Education. University of Michigan.

- ↑ Wolgemuth, Kathleen L. (April 1959). "Woodrow Wilson and Federal Segregation". The Journal of Negro History (Association for the Study of African-American Life and History, Inc.) 44 (2): 158-173. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2716036?seq=1.

- ↑ "President Wilson House, Dergalt". Northern Ireland - Ancestral Heritage. Northern Ireland Tourist Board.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Woodrow Wilson — 28th President, 1913-1921".

- ↑ White, William Allen. "Chapter II: The Influence of Environment". Woodrow Wilson - The Man, His Times and His Task. http://books.google.com/books?id=pXYqVxLyRrwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Woodrow+Wilson:+The+Man,+His+Times+and+His+Task#PPA28,M1.

- ↑ Link Road to the White House pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Walworth ch 1

- ↑ Link, Wilson I:5-6; Wilson Papers I: 130, 245, 314

- ↑ The World's Work: A History of our Time, Volume IV: November 1911-April 1912. ???: Doubleday. 1912. pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Link, Arthur S. (1978). "Wilson, Woodrow". in Alexander Leitch. A Princeton Companion. Princeton University Press. http://etcweb.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/wilson_woodrow.html. Retrieved on 2008-10-29. "His doctoral dissertation, Congressional Government (1885), brought immediate fame and academic appointments at Bryn Mawr College (1885-88) and Wesleyan University (1888-90).".

- ↑ Health of Woodrow Wilson

- ↑ The Pierce Arrow Limousine from the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library

- ↑ Richard F. Weingroff, President Woodrow Wilson – Motorist Extraordinaire, Federal Highway Administration

- ↑ CNNSI.com - Statitudes - Statitudes: World Series, By the Numbers - Thursday October 17, 2002 03:33 AM

- ↑ for details on Wilson's health see Edwin A. Weinstein, Woodrow Wilson: A Medical and Psychological Biography (Princeton 1981)

- ↑ Wilson Congressional Government 1885.

- ↑ "Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921)". Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia (2005-01-14). Retrieved on 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Mulder, John H. (1978). Woodrow Wilson: The Years of Preparation. Princeton. pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Wilson Congressional Government 1885, p. 180.

- ↑ The Politics of Woodrow Wilson, 41–48

- ↑ Wilson Congressional Government 1885, p. 205.

- ↑ Wilson Congressional Government 1885, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Wilson Congressional Government 1885, p. 76.

- ↑ Wilson Congressional Government 1885, p. 132.

- ↑ David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, "Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900,"Independent Review 4 (Spring 2000), 555-75.

- ↑ Frozen Republic, 145

- ↑ "Beyond FitzRandolph Gates," Princeton Weekly Bulletin June 22, 1998.

- ↑ Walworth 1:109

- ↑ Henry Wilkinson Bragdon, Woodrow Wilson: The Academic Years (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967), 326-327.

- ↑ PBS - American Experience: Woodrow Wilson Wilson- A Portrait

- ↑ Walworth v 1 ch 6, 7, 8

- ↑ Biography of Woodrow Wilson (PDF), New Jersey State Library.

- ↑ Shenkman, Richard. p. 275. Presidential Ambition. New York, New York. Harper Collins Publishing, 1999. First Edition. 0-06-018373-X

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Rouse, Robert (March 15, 2006). "Happy Anniversary to the first scheduled presidential press conference - 93 years young!", American Chronicle.

- ↑ William Bullitt; Sigmund Freud (1998). Woodrow Wilson - A Psychological Study. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. pp. 150.

Bullitt knew Wilson personally, and was with him at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. - ↑ "America's Unknown Enemy: Beyond Conspiracy". American Institute of Economic Research.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Born of a panic: Forming the Federal Reserve System". Minnesota Federal Reserve (1988-08).

- ↑ Whithouse, Michael (1989-05). "Paul Warburg's Crusade to Establish a Central Bank in the United States". Minnesota Federal Reserve.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Johnson, Roger (1999-12). "Historical Beginnings… The Federal Reserve". Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

- ↑ (Congressional Record, 12/22/1913)

- ↑ Keleher, Robert (1997-03). "The Importance of the Federal Reserve". Joint Economic Committee. US House of Representatives.

- ↑ Arthur Link, Wilson: The New Freedom; pp. 199-240 (1956).

- ↑ Ask Yahoo! November 10, 2005

- ↑ The $100,000 bill Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

- ↑ The Tragedy of American Diplomacy from William Appleman William p. 72

- ↑ Records of the Farm Credit Administration

- ↑ Keating-Owen Act (ClassBrain.com)

- ↑ FindLaw.com

- ↑ "Woodrow Wilson and Federal Segregation", Kathleen L. Wolgemuth, The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 44, No. 2 (April, 1959 ), p. 158

- ↑ Wolgemuth, op. cit.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Henry (January 1963). "Woodrow Wilson and the Race Question". The Journal of Negro History (Association for the Study of African-American Life and History, Inc.) 48 (1): 1-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2716642?seq=1.

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson: Speech of Acceptance

- ↑ The American Presidency Project Wison Qoute

- ↑ "Primary Documents: U.S. Declaration of Neutrality, 19 August 1914". 7 January 2002. <http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/usneutrality.htm>.

- ↑ Declaration of war speech (FirstWorldWar.com)

- ↑ Avrich, Paul, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background, Princeton University Press, 1991

- ↑ Records of the Committee on Public Information from the National Archives

- ↑ http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&displayDate=4/2&categoryId=worldwari

- ↑ Baker, Ray Stannard.(1937). "Woodrow Wilson Life and Letters". Garden City, New York.

- ↑ "Woodrow Wilson's War Message". <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/ww18.htm>.

- ↑ "Opposition to Wilson's War Message". <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/doc19.htm>.

- ↑ "Opposition to Wilson's War Message". <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/doc19.htm>.

- ↑ You want a more 'progressive' America? Careful what you wish for. csmonitor.com

- ↑ President Wilson's Fourteen Points

- ↑ Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani, The First Cold War: The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson in U.S.-Soviet Relations. (2002) p. 202.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. 1918. Preface. Table of Contents

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson bio sketh from NobelFoundation.org

- ↑ CTV.ca U.S. historians pick top 10 presidential errors

- ↑ Leonard Williams Levy and Louis Fisher, Encyclopedia of the American Presidency, Simon and Schuster: 1994, p. 494. ISBN 0132759837

- ↑ The successful Communist takeover of Russia in 1917 was also a background factor: many anarchists believed that the worker's revolution that had taken place there would quickly spread across Europe and the United States. Paul Avrich, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background, Princeton University Press, 1991

- ↑ Indiana Supreme Court Legal History Lecture Series, "Three Generations of Imbeciles are Enough:" Reflections on 100 Years of Eugenics in Indiana, at The Indiana Supreme Court

- ↑ Williams v. Smith, 131 NE 2 (Ind.), 1921, text at [1]

- ↑ Larson 2004, p. 194-195 Citing Buck v. Bell 274 U.S. 200, 205 (1927)

- ↑ Primary Documents: President Woodrow Wilson's Address in Favor of the League of Nations, September 25, 1919 (FirstWorldWar.com)

- ↑ Phyllis Lee Levin. Edith and Woodrow: The Wilson White House. Simon and Schuster. New York. 2001, p139

- ↑ Walter Russell Mead, Special Providence, (2001)

- ↑ David M. Kennedy, "What 'W' Owes to 'WW': President Bush May Not Even Know It, but He Can Trace His View of the World to Woodrow Wilson, Who Defined a Diplomatic Destiny for America That We Can't Escape." The Atlantic Monthly Vol: 295. Issue: 2. (March 2005) pp 36+.

- ↑ Arthur Link, Wilson:The Road to the White House (Princeton University Press, 1947) 502

- ↑ Ellis, Mark. "'Closing Ranks' and 'Seeking Honors': W. E. B. Du Bois in World War I" Journal of American History, 1992 79(1): 96-124. ISSN 0021-8723 Fulltext in Jstor

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson, A History of the American People (1931) V:59.

- ↑ Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson 68:298

- ↑ American Rhetoric, "Final Address in Support of the League of Nations", Woodrow Wilson, delivered 25 Sept 1919 in Pueblo, CO. John B. Duff, "German-Americans and the Peace, 1918-1920" American Jewish Historical Quarterly 1970 59(4): 424-459. and Duff, "The Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans" Journal of American History 1968 55(3): 582-598. ISBN 0021-8723

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson proclaims the first Mother’s Day holiday from the History Channel

- ↑ David Henry Burton. Theodore Roosevelt, American Politician, p.146. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997, ISBN 0838637272

- ↑ John Whitcomb, Claire Whitcomb. Real Life at the White House, p.262. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0415939518

References

- Link, Arthur S. (editor). The Papers of Woodrow Wilson. http://www.pupress.princeton.edu/catalogs/series/pw.html. Complete in 69 volumes at major academic libraries. Annotated edition of all of Wilson's correspondence, speeches and writings.

- Tumulty, Joseph P. (1921). Woodrow Wilson as I Know Him. http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext05/8wwik10.txt.. Memoir by Wilson's chief of staff.

- The New Freedom by Woodrow Wilson at Project Gutenberg 1912 campaign speeches

- Wilson, Woodrow (1917). Why We Are at War. http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext04/whwar10h.htm. Six war messages to Congress, January - April 1917.

- Wilson, Woodrow. Selected Literary & Political Papers & Addresses of Woodrow Wilson. 3 volumes, 1918 and later editions.

- Woodrow Wilson, compiled with his approval by Hamilton Foley; Woodrow Wilson's Case for the League of Nations, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1923; contemporary book review.

- Wilson, Woodrow. Messages & Papers of Woodrow Wilson 2 vol (ISBN 1-135-19812-8)

- Wilson, Woodrow. The New Democracy. Presidential Messages, Addresses, and Other Papers (1913-1917) 2 vol 1926 (ISBN 0-89875-775-4

- Wilson, Woodrow. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points (1918).

- 'Wilson and the Federal Reserve'

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E., “Woodrow Wilson and George W. Bush: Historical Comparisons of Ends and Means in Their Foreign Policies,” Diplomatic History, 30 (June 2006), 509–43.

- Bailey; Thomas A. Wilson and the Peacemakers: Combining Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace and Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1947)

- Bennett, David J., He Almost Changed the World: The Life and Times of Thomas Riley Marshall (2007)

- Brands, H. W. Woodrow Wilson 1913-1921'’ (2003)