Winnipeg

| City of Winnipeg | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): Heart of the Continent, Gateway to the West, One Great City, Peg City, The Peg, Winterpeg, The 204 | |||

| Motto: Unum Cum Virtute Multorum (One with the Strength of Many) |

|||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | Canada |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Manitoba |

||

| Region | Winnipeg Capital Region | ||

| Established, | 1738 (Fort Rouge) | ||

| Renamed | 1822 (Fort Garry) | ||

| Incorporated | 1873 (City of Winnipeg) | ||

| Government | |||

| - City Mayor | Sam Katz | ||

| - Governing Body | Winnipeg City Council | ||

| - MPs |

List of MPs

|

||

| - MLAs |

List of MLAs

|

||

| Area | |||

| - Land | 464.01 km² (179.2 sq mi) | ||

| - Urban | 448.92 km² (173.3 sq mi) | ||

| - Metro | 5,302.98 km² (2,047.5 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 238 m (781 ft) | ||

| Population (2006 Census[1][2]) | |||

| - City | 633,451 (Ranked 7th) | ||

| - Density | 1,365/km² (3,535.3/sq mi) | ||

| - Urban | 641,483 (Ranked 9th) | ||

| - Urban Density | 1,429/km² (3,701.1/sq mi) | ||

| - Metro | 694,668 (Ranked 8th) | ||

| - Metro Density | 131/km² (339.3/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CST (UTC−6) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC−5) | ||

| Postal code span | R2C–R3Y | ||

| Area code(s) | 204 | ||

| Demonym | Winnipegger | ||

| NTS Map | 062H14 | ||

| GNBC Code | GBEIN | ||

| Website: City of Winnipeg | |||

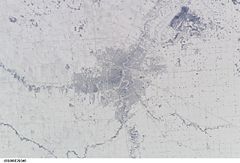

Winnipeg (pronounced /ˈwɪnɨpɛg/) is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Manitoba. It is located near the longitudinal centre of North America,[3] at the confluence of the historic Red and Assiniboine Rivers, a point now commonly known as The Forks.[4] Winnipeg ("muddy waters" in western cree) is named after an aboriginal description of the darker coloured water that flows through the area, due to the soil and clay content. Winnipeg is the core cultural and economic centre for the Winnipeg Capital Region, which has a combined population of 730,305. Winnipeg is the 7th largest municipality in Canada with a total population of 633,451.[5]

The city is located in the prairies of Western Canada, in a native tallgrass prairie/aspen parkland ecosystem, and boasts such cultural attractions as the Royal Winnipeg Ballet and the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra.[6] It is home to historic architecture; distinctive neighbourhoods, (like Saint Boniface and the Exchange District); scenic waterways; a Canadian heritage river; and numerous parks, including Assiniboine Park and Kildonan Park.

Winnipeg also lies relatively close to many beautiful Canadian Shield rivers and hundreds of lakes and parks, including Lake Winnipeg (the earth's 11th largest freshwater lake).[7]

Winnipeg has laid claim to the title of World's Longest Skating Rink, along the Red and Assiniboine rivers.[8]

Contents |

History

Before Incorporation

Winnipeg lies at the confluence of the Assiniboine River and the Red River, known as The Forks, a historic focal point on canoe river routes travelled by Aboriginal peoples for thousands of years.[9] The name Winnipeg is a transcription of a western Cree word meaning "muddy waters"; the general area was populated for thousands of years by First Nations. In prehistory, through oral stories, archaeology, petroglyphs, rock art, and ancient artifacts, it is known that natives would use the area for camps, hunting, fishing, trading, and further north, agriculture. The first farming in Manitoba appeared to be along the Red River, near Lockport, Manitoba, where maize (corn) and other seed crops were planted before contact with Europeans. For thousands of years there have been humans living in this region, and there are many archaeological clues about their ways of life. The rivers provided transportation far and wide and linked many peoples-such as the Assiniboine, Ojibway, Anishinaabe, Mandan, Sioux, Cree, Lakota, and others—for trade and knowledge sharing. Ancient mounds were once made near the waterways, similar to that of the mound builders of the south. Lake Winnipeg was considered to be an inland sea, with important river links to the mountains out west, the Great Lakes to the east, and the Arctic Ocean in the north. The Red River linked ancient northern and southern peoples along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. The first maps of some areas were made on birch bark by the Ojibway, which helped fur traders find their way along the rivers and lakes.

Settlement

The first French officer arrived in the area in 1738. Sieur de la Vérendrye built the first fur trading post on the site (Fort Rouge) for the North West Company, who continued to trade there for several decades before the arrival of the Hudson's Bay Company.[10] The Metis hunted, traded, and lived in the general area for decades. Lord Selkirk was involved with the first permanent settlement, purchase of land from the Hudson's Bay Company, and a survey of river lots in the early 1800's. Fort Gibraltar was built by the North West Company in 1809, and Fort Douglas was built by the Hudson's Bay Company in 1812. The two companies fought fiercely over trade in the area, and each destroyed some of the other's forts over the course of several battles. The Metis and Lord Selkirk settlers fought a battle at the historic seven oaks site. In 1821, the Hudson's Bay and North West Companies ended their long rivalry with a merger. Fort Gibraltar, within the site of present-day Winnipeg, was renamed Fort Garry in 1822 and became the leading post in the region for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Fort Garry was destroyed in an 1826 flood and rebuilt in 1835. It remained the residence of the Governor of the company for many years and became a part of the major first colony and settlement in western Canada.

In 1869–70, Winnipeg was the site of the Red River Rebellion, a conflict between the local provisional government of Métis, led by Louis Riel, and the newcomers from eastern Canada; General Garnet Wolseley was sent to put down the rebellion. This rebellion led directly to Manitoba's entry into Canadian Confederation as Canada's fifth province in 1870, and on November 8, 1873, Winnipeg was incorporated as a city. The settlement was named by Manitoba and Northwest Territories legislator James McKay.[11]

Late 1800's & early 20th century

With the recent Canadian Pacific Railway came many travelers, settlers, and businessmen to the new city. Agriculture was a booming industry, and many made massive fortunes on the prairies. Bonanza farms were common at the time further south in the United States. Canada was also eager to settle the west before American interests and railways interfered in any way. Winnipeg's economic boom during the 1890s and early 20th century allowed it to take on its distinctive multicultural character, and the city was Canada's third largest for many years. The Manitoba Legislative Building reflects the optimism of the boom years. Built mainly of Tyndall Stone and opened in 1920, its dome supports a bronze statue finished in gold leaf titled, "Eternal Youth and the Spirit of Enterprise" (commonly known as the "Golden Boy"). Many new lots of land were sold, and prices increased fast due to high demand. The real estate boom eventually slowed down, and Vancouver soon became the third largest city.

Winnipeg faced financial difficulty when the Panama Canal opened in 1914. The canal reduced reliance on Canada's rail system for international trade, and the increase in ship traffic helped Vancouver surpass Winnipeg to become Canada's third-largest city in the 1960s.[12]

Following World War I, owing to a postwar recession, appalling labour conditions, and the presence of radical union organizers and a large influx of returning soldiers, 35,000 Winnipeggers walked off the job in May 1919 in what came to be known as the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. After many arrests, deportations, and incidents of violence, the strike ended on June 21, 1919, when the Riot Act was read and a group of RCMP officers charged a group of strikers. Two strikers were killed and at least thirty others were injured, resulting in the day being known as Bloody Saturday; the lasting effect was a polarized population. One of the leaders of the strike, J. S. Woodsworth, went on to found Canada's first major socialist party, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which would later become the NDP.

The stock market crash of 1929 only hastened an already steep decline in Winnipeg; the Great Depression resulted in massive unemployment, which was worsened by drought and depressed agricultural prices. The Depression ended when World War II started in 1939. In Winnipeg, the old established armouries of Minto, Tuxedo (Fort Osborne), and McGregor were so crowded that the military had to take over other buildings to increase capacity.

The end of World War II brought a new sense of optimism in Winnipeg. Pent-up demand brought a boom in housing development, but building activity came to a halt due to the 1950 Red River Flood, the largest flood to hit Winnipeg since 1861; the flood held waters above flood stage for 51 days. On May 8, 1950, eight dikes collapsed, four of the city's eleven bridges were destroyed, and nearly 100,000 people had to be evacuated, making it Canada's largest evacuation in history. The federal government estimated damages at over $26-million, although the province insisted it was at least double that.[13]

Amalgamation to Present

Prior to 1972, Winnipeg was the largest of thirteen cities and towns in a metropolitan area around the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Unicity was created on July 27, 1971 and took effect with the first elections in 1972. The City of Winnipeg Act incorporated the current city of Winnipeg: the municipalities of Transcona, St. Boniface, St. Vital, West Kildonan, East Kildonan, Tuxedo, Old Kildonan, North Kildonan, Fort Garry, Charleswood, and St. James, were amalgamated with the Old City of Winnipeg.

Immediately following the 1979 energy crisis, Winnipeg experienced a severe economic downturn in advance of the early 1980s recession. Throughout the recession, the city incurred closures of prominent businesses such as the Winnipeg Tribune and the Swift's and Canada Packers meat packing plants.[14] In 1981, Winnipeg was one of the first cities in Canada to sign a tripartite agreement to redevelop its downtown area.[15] The three levels of government—federal, provincial and municipal—have contributed over $271-million to the development needs of downtown Winnipeg over the past 20 years. The funding was instrumental in attracting Portage Place mall, which comprises the headquarters of Investors Group, the offices of Air Canada, and several apartment complexes. In 1989, the reclamation and redevelopment of the CNR rail yards at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers turned The Forks into Winnipeg's most popular tourist attraction.[16]

In 1996 Winnipeg's National Hockey League team (the Winnipeg Jets) left for Phoenix, Arizona.

The 1997 Red River Flood, (Flood of the Century) devastated communities along the Red River, from Fargo, North Dakota to Winnipeg. The floodway was pushed to its limits in 1997, which led to the Red River Floodway Expansion, set to be completed in late 2010 at a final cost of more than $665,000,000 CAD.

Geography

Winnipeg is situated on the tall grass plains of south-central Manitoba, in the Canadian Prairies of Western Canada; near the geographical centre of North America; approximately 100 km (62 mi) north of the border with the United States; and 70 km (43 mi) south of Lake Winnipeg. It is situated on the flat, rich agricultural land of the Red River of the North, In an area known as the Red River Valley. The valley which which was formed from the ancient glacial Lake Agassiz, has rich deposits of black soil that are ideal for growing bountiful crops. The highest points near the city are north east in Birds Hill Provincial Park and the town of Birds Hill, which were islands made by glaciers moving and depositing large volumes of sand and rocks. The city is extremely isolated, and the closest city with a metro over 1 million, (Minneapolis), is approximately 700 km (430 miles) southeast, and the closest city with a metro around 200,000 (Fargo) is approximately 358 km (222 miles) south. The city's four major rivers include the Red, Assiniboine, La Salle River, and Seine rivers; all of which eventually flow into the Red River. The Red River flows north toward Lake Winnipeg, and Lake Winnipeg flows into the Nelson River that drains into Hudson Bay. Fur trade goods from the region were first transported north through Hudson Bay, or east through Lake Superior. According to the Census geographic units of Canada, the city has a total area of 464.01 km² (179.2 sq mi), making it by far the largest city in the Red River Valley.

Neighbourhoods

- See also: List of Winnipeg neighbourhoods and List of Winnipeg's 10 tallest buildings

Winnipeg has many distinctive neighbourhoods.

Downtown Winnipeg includes the Exchange District, The Waterfront District, The Forks, Central Park, Broadway-Assiniboine, and Chinatown. It is roughly three square kilometres and comparable to the downtowns of much larger North American cities such as Philadelphia (metro pop. 6.2 million) and San Francisco (7.0 million). Some trendy areas near the downtown core include The French Quarter (St. Boniface), Osborne Village, and Little Italy.

Other major neighbourhoods include River Heights, Crescentwood, Charleswood, Fort Garry, Fort Rouge, Grant Park, North Kildonan, West Kildonan, East Kildonan,The Maples, The North End, North Point Douglas, Polo Park, St. James, St. Norbert, St. Vital, Transcona, Tuxedo, Wildwood, Wolseley, Whyte Ridge, Linden Woods, Island Lakes, and Waverly West.[17]

Climate

| for Winnipeg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

20

-13

-23

|

15

-9

-19

|

22

1

-11

|

32

10

-2

|

59

19

5

|

90

23

11

|

71

26

13

|

75

25

12

|

52

19

6

|

36

11

-0

|

25

-1

-10

|

19

-10

-19

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| temperatures in °C precipitation totals in mm source: Environment Canada[18][18] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Imperial conversion

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Due to its location on the Great Plains (Canadian Prairies), and its distance from both mountains and oceans, Winnipeg has an extreme humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb), USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 3a,[19] in that there are great differences between summer and winter temperatures. Summers are warm and often humid, Spring and autumn are highly variable seasons, and its winters are long and sometimes dangerously cold. Because of the openness of the landscape; Winnipeg lies exposed to numerous weather systems throughout the year; including cold arctic high pressure systems from the northwest during the winter season; and hot, humid weather drawn northward from the Gulf of Mexico during the summer season. The city has acquired the nickname 'Winterpeg' because of the long cold snowy winters. Only once since record keeping has the city failed to witness a 'white Christmas'. From December through February the maximum daily temperature exceeds 0 °C (32 °F), on average, for only 10 days and the minimum daily temperature falls below -20 °C (-4 °F) on 49 days. Winnipeg is also ranked fourth amoung Canada with 49 wind chill days at -30 °C (-22 °F) or less.[20]

Winnipeg is a sunny city with an average of 317 sunny days per year.[21] and all seasons are characterized by an abundance of sunshine. Winnipeg has Canada's second-clearest skies year-round and is the second sunniest city in Canada in the spring and winter.[21]

Its summers can be humid, annually temperatures average 45, 11 and 2 days with humidex (combined temperature & humidity index) above 30 °C (86 °F), 35 °C (95 °F) and 40 °C (104 °F) respectively.[22] However the city only averages 13 days a year where temperatures actually reaches 30 °C or higher.[23] The Red River Valley has a fairly long frost-free season, consisting of between 120 and 140 days[24]. Winnipeg usually has 27 days with thunderstorms per year.[22] Some snow in spring and autumn is normal. Similarly, late heat waves as well as Indian summers are a regular feature of the climate. A typical year will see an extreme range of temperatures from -35°C (-31°F) to 35°C (95°F), though both colder and warmer temperatures have been recorded.

The highest temperature recorded in Winnipeg was 42.2 °C (108 °F) on July 11, 1936. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Winnipeg was −47.8 °C (−54.0 °F), on December 24, 1879.[25] The coldest wind chill reading ever recorded was −57.1 °C (−70.8 °F), on February 1, 1996.[18] The highest humidex reading recorded in Winnipeg was 48 °C (118 °F) on July 25, 2007, although just 64 km (40 mi) southwest of the city, in the town of Carman, Manitoba broke Canada's all time humidex record, with a high of 53 °C (127 °F), July 25, 2007.[26]

Destructive weather events such as tornadoes, major floods, extreme heat waves, droughts, severe hail, blizzards, freezing rain, extreme wind chills, fog, and sleet; have all occurred within or near the Winnipeg area. Like Chicago, Winnipeg is also known as a windy city. The average annual wind speed is 16.9 km/h (10.5 mph), predominantly from the south.[27] The city has experienced wind gusts of up to 129 km/h (80 mph). Tornadoes are not uncommon in the area, particularly in the spring and summer months; a rare F5 tornado (strongest ever recorded in Canada) hit Elie, just 40 km (25 miles) west of Winnipeg.

Economy

- See also: List of corporations based in Winnipeg and List of hospitals in Manitoba

Winnipeg is an important regional centre of commerce, industry, culture, finance, and government. According to the Conference Board of Canada, Winnipeg had the third-fastest growing economy among Canada's major cities in 2007, with a real GDP growth at 3.7%.[28]

Approximately 375,000 people are employed in Winnipeg and the surrounding area. Some of Winnipeg's largest employers are either government or government-funded institutions, including: the Province of Manitoba, the City of Winnipeg, the University of Manitoba, the Health Sciences Centre, the Casinos of Winnipeg, and Manitoba Hydro. Approximately 54,000 people (14% of the work force) are employed in the public sector. Large private sector employers include: Manitoba Telecom Services, Canwest, Palliser Furniture, Great-West Life Assurance, Motor Coach Industries, Convergys Corporation, New Flyer Industries, Boeing Canada Technology, Bristol Aerospace, Nygård International, Canad Inns and Investors Group.

A number of large privately held family-owned companies operate out of Winnipeg. The most famous of these is James Richardson & Sons. The Richardson Building at Portage and Main was the first skyscraper to grace that corner. Other private companies include Ben Moss Jewellers, Frantic Films and Paterson Grain.

The Royal Canadian Mint located in eastern Winnipeg (on Route 20 (Lagimodière Blvd)) is where all circulating coinage in Canada is produced. The plant, established in 1975, also produces coins for many other countries in the world.

Winnipeg is home to several government research labs. The National Microbiology Laboratory is Canada's front line in its response to infectious diseases and one of only a handful of Biosafety level 4 microbiology laboratories in the world. The National Research Council also has the Institute for Biodiagnostics laboratory located in the downtown area.

In 2003 and 2004, Canadian Business magazine ranked Winnipeg in the top 10 cities for business. In 2006, Winnipeg was ranked by KPMG as one of the lowest cost locations to do business in Canada.[29] As with much of Western Canada, in 2007, Winnipeg experienced both a building and real estate boom. In May 2007, the Winnipeg Real Estate Board reported the best month in its 104-year history in terms of sales and volume.[30]

Demographics

| Ethnic Origins[31] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population | Percentage | |

| English | 141,480 | 22.6 |

| Scottish | 114,960 | 18.4 |

| German | 106,260 | 17.0 |

| Canadian | 104,130 | 16.6 |

| Ukrainian | 96,255 | 15.4 |

| Irish | 86,580 | 13.9 |

| Polish | 50,555 | 8.1 |

| French | 47,165 | 6.6 |

| Scandinavian | 45,215 | 7.2 |

| Visible minorities[32] | ||

| Population | Percentage | |

| Total | 101,910 | 16.3 |

| Filipino | 36,820 | 5.9 |

| South Asian | 15,080 | 2.4 |

| Black | 14,200 | 2.3 |

| Chinese | 12,660 | 2.0 |

| Latin American | 5,390 | 0.9 |

| Southeast Asian | 5,325 | 0.9 |

| Multiple | 3,060 | 0.5 |

| Arab | 2,115 | 0.3 |

| Korean | 2,065 | 0.3 |

| West Asian | 1,885 | 0.3 |

| Japanese | 1,725 | 0.3 |

| Other | 1,585 | 0.3 |

| Aboriginal identity[33] | ||

| Population | Percentage | |

| Total | 63,745 | 10.19 |

| Métis | 37,385 | 5.97 |

| North American Indian | 24,950 | 3.99 |

| Inuit | 280 | 0.04 |

| Multiple | 355 | 0.06 |

| Other | 770 | 0.12 |

According to the 2006 Census, there were 633,451 people residing in Winnipeg itself and a total of 694,668 inhabitants in the Winnipeg Census Metropolitan Area on 16 May 2006, and 711,455 in the Winnipeg Capital Region making it Manitoba’s largest city and the eighth largest CMA in Canada.[2] [34] Of the city population, 48.3% were male and 51.7% were female. 24.3% were 19 years old or younger, people aged by 20 and 39 years accounted for 27.4%, and those between 40 and 64 made up 34.0% of the population. The average age of a Winnipegger in May 2006 was 38.7, compared to an average of 39.5 for Canada as a whole.[35]

Between the censuses of 2001 and 2006, Winnipeg's population increased by 2.2%, compared to the average of 2.6% for Manitoba and 5.4% for Canada. The population density of the city of Winnipeg averaged 1,365.2 people per square kilometre, compared with an average of 3.5 for Manitoba.

Of Winnipeg’s total population, 61,217 citizens live in the city’s Census Metropolitan Area,[36] which apart from Winnipeg includes the Rural municipalities of East St. Paul, Headingley, Ritchot, Rosser, Springfield, St. Clements, St. François Xavier, Taché and West St. Paul, and the Aboriginal community of Brokenhead.

Ethnicity

Ethnic diversity is an important part of Winnipeg's culture. Most Winnipeggers are of European or Canadian descent. Visible minorities make up 16.3% of Winnipeg's population. Winnipeg is home to 38,155 people of Filipino descent, or roughly 6% of the total population, the highest concentration of persons of Filipino origin in Canada, and the second largest Filipino population in Canada after Toronto.[31][37]

Language

More than 20 languages are spoken in Winnipeg; the most common is English, in which 99.0% of Winnipeggers are fluent. In terms of Canada's official languages, 88.0% of Winnipeggers speak only English, and 0.1% speak only French. 11% speak both English and French, while 0.9% speak neither English nor French. Other languages spoken in Winnipeg include German (spoken by 4.1% of the population), Tagalog (3.4%), Ukrainian (3.1%), Spanish, Chinese and Polish (all three spoken by 1.7% of the population), as well as Aboriginal languages including Ojibway (0.6%), Cree (0.5%), Inuktitut and Mi'kmaq (both less than 0.1%). Other languages spoken in Winnipeg include Portuguese, Italian, Icelandic, Punjabi, Vietnamese, Urdu, Hindi, Russian, Dutch, Non-verbal languages, Arabic, Serbian, Greek, Hungarian, Japanese, Creole, Danish, and Gaelic languages (all of which are spoken by roughly 1% or less of the population).[38]

Religion

The 2001 census states that 21.7% of Winnipeggers do not follow a religion.[39], while 72.9% of Winnipeggers belong to a Christian denomination, 35.1% of which are Protestant, 32.6% are Roman Catholic, and 5.2% are other Christian denominations. 5.6% of the population follows a religion other than Christianity—followers of Judaism make up 2.1% of the population, followers of Buddhism and Sikhism make up 0.9% of the population each, and Muslims make up 0.8% of the population. Hindus account for 0.6% of the population, while followers of other religions make up less than 0.5% of the population.

Culture

- See also: List of Winnipeg musicians, List of TV and films shot in Winnipeg, List of tallest buildings in Winnipeg, List of Winnipeggers, and Winnie-the-Pooh

Winnipeg is well known across the prairies for its arts and culture.[40]

Since 1999, Winnipeg has achieved acclaim for being the "Slurpee Capital of the World".[41]

Winnipeg is the only Canadian city to ever host the Pan American Games, and the second city in the world to host the event twice, once in 1967 and once in 1999.[42]

Winnipeg is well known for its murals.[43] Many buildings in the downtown area and extending into some suburban areas have murals painted on the sides of buildings.[44] Although some are advertisements for shops and other businesses, many are historical paintings, school art projects, or downtown beautification projects. Murals can also be found on several of the downtown traffic light switch posts and fire hydrants.

Winnipeg also has a thriving film community, beginning as early as 1897 with the films of James Freer to the production of local independent films of today, such as those by Guy Maddin. It has also supported a number of Hollywood productions, including Shall We Dance? (2004), the Oscar nominated film Capote (2005), The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2006), The Horsemen (2008) and X2 (2003) had parts filmed in the province. Several locally-produced and national television dramas have also been shot in Winnipeg. The National Film Board of Canada and the Winnipeg Film Group have produced numerous award-winning films.

Guy Maddin's My Winnipeg, an independent film released in 2008, is a poetic and comedic rumination on the city's history. It features archival footage and contemporary imagery blended seamlessly into an extended autobiographical goodbye letter.

There are several TV and film production companies in Winnipeg. Some of the prominent ones are Frantic Films, Buffalo Gal Pictures, Les Productions Rivard and Eagle Vision.

Winnipeg Bear, (also known as Winnie-the-Pooh) was purchased in Ontario, by Lieutenant Harry Colebourn of The Fort Garry Horse cavalry regiment en route to his embarkation point for the front lines of World War I. He named the bear after the regiment's home town of Winnipeg.

An Ernest H. Shepard painting of "Winnie the Pooh" is the only known oil painting of Winnipeg’s famous bear cub. It was purchased at an auction for $285,000 in London, England, in 2000. The painting is displayed in Assiniboine Park.

Winnipeg is also associated with various music acts. Among the most notable are Neil Young, The Guess Who, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Streetheart, Harlequin, Chantal Kreviazuk, Bif Naked, Comeback Kid, The Waking Eyes, Econoline Crush, Brent Fitz, Jet Set Satellite, the New Meanies, Propagandhi, The Weakerthans, The Perpetrators, Crash Test Dummies, Christine Fellows, The Wailin' Jennys and The Duhks.

Winnipeg is the subject of the song "One Great City!" by The Weakerthans. The song makes allusion to the slow growth and lost industry in the town.[45] The title of the song is the slogan on signs welcoming visitors to Winnipeg. The city is also mentioned in Neil Young's "Don't Be Denied". Aaron Funk, a Winnipeg-based Breakcore artist better known as Venetian Snares, released a concept album in 2005 based on his hatred of Winnipeg.

Winnipeg is mentioned in the song "Anywhere Under the Moon" by Canadian folk duo Dala, on their 2007 album Who Do You Think You Are, as well as in Danny Michel's song "Into the Flame".

The Winnipeg Public Library is a public library network with 20 branches throughout the city, including the Millennium Library, located downtown.

Cuisine

Winnipeg has a broad selection of restaurants and specialty food stores. Many ethnic cuisines are well represented, including those of the local Ukrainian, Jewish, Mennonite, Chinese, Italian, Korean, Greek, Thai, French, Vietnamese, and Filipino populations.

Regional dishes include Winnipeg goldeye, a kind of smoked fish, fresh pickerel fillets and pickerel cheeks, and an East European style of light rye bread called Winnipeg rye. Also associated with Winnipeg are nips (hamburgers) from Salisbury House restaurant, Jeanne's cake, Russian mints from Morden's Chocolate, Old Dutch potato chips, and beer from Half Pints and Fort Garry breweries.

Local media

Winnipeg has two daily newspapers, six English television stations, one French television station, 24 AM and FM radio stations and a variety of regional and nationally based magazines that call the city home.

Festivals

The city is home to several large festivals. The Winnipeg Fringe Theatre Festival is North America's second largest Fringe Festival, held every July. The Winnipeg International Writers Festival (THIN AIR) rivals similar festivals in Calgary and Vancouver. Other festivals include Folklorama, the Jazz Winnipeg Festival, the Winnipeg Folk Festival, the Winnipeg Music Festival, the Red River Exhibition, and Festival du Voyageur.

City life

Attractions

- The Royal Canadian Mint located in eastern Winnipeg (on Route 20 (Lagimodière Blvd)) is where all circulating coinage in Canada is produced. The plant, established in 1975, also produces coins for many other countries in the world.

- Winnipeg is the future home of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. The start of construction is contingent on continued efforts to raise money in 2008. It will be the first Canadian national museum outside of the National Capital Region. The museum will be located at The Forks.

- FortWhyte Alive nature centre, located in the south west section of the city is a very popular attraction.

- The Manitoba Electrical Museum is completely free of charge and has six themes and a lower level.

- Pan Am Pool was home to the Pan American Games and is located in the southern section of the city.

- Club Regent Casino located on Regent Ave, and McPhillips Street Station Casino are the city's two main Casinos.

- The Manitoba Museum (formerly Museum of Man and Nature) is the largest museum in the province. It has nine galleries and includes a planetarium as well as a replica of the Nonsuch. It is one of the only attractions to receive the Michelin Guide's highest rating as an attraction in Winnipeg.[46]

- The Winnipeg Railway Museum, located on tracks 1 and 2 in the Via Rail Station is home to The Countess of Dufferin, the first locomotive on the Canadian Prairies.

- The city is home to the Western Canada Aviation Museum, the second largest aviation museum in Canada. The museum is housed in a Trans-Canada Air Lines hangar and contains the most complete Vickers Viscount in the world along with the last remaining Fokker Universal.

- The Costume Museum of Canada now resides in Winnipeg's Exchange District. After 23 years in outlying Dugald, the museum has recently relocated to the capital city with hopes to attract even more visitors. It is home to approximately 35,000 articles of clothing and represents about 400 years of fashion history in Canada.

- The Fort Garry Hotel is one of Canada's National Historic Sites as well as haunted.

- The Winnipeg Firefighters Historical Society Museum housed in a former fire station contains memorabilia dating back to the beginning of the Winnipeg Fire Brigade in 1882, including fully operational fire apparatus such as a 1927 American LaFrance and a 1958 Mack truck.

- Winnipeg has laid claim to the title of World's Longest Skating Rink, along the Red and Assiniboine rivers[8] beating out the nation's capital Ottawa with its Rideau Canal.

- The Royal Winnipeg Ballet is Canada's oldest ballet and the longest continually operating ballet company in North America.[47] It is the first Canadian company to tour Russia and Czechoslovakia and the first western company to tour Cuba.[48] It is the only ballet company in Canada to receive a Royal charter in 1953 from Queen Elizabeth II.[49]

- The Manitoba Theatre Centre is Canada's first regional theatre.[50] It was founded in 1957 and has produced just fewer than 500 plays featuring actors such as Len Cariou, Gordon Pinsent, Keanu Reeves and William Hurt.

- Winnipeg is home to several of Canada's national historic sites including; The Forks, the Red River Floodway, the Fort Garry Hotel, Confederation Building, the Exchange District, Fort Douglas and Lower Fort Garry (20 mi (32 km) from the original Fort Garry).

- The MTS Centre is now the 19th busiest arena in the world. Also the arena now sits 11th among facilities in North America, its highest ranking ever, and it remains in the 3rd spot in Canada, after the Bell Centre in Montreal (fourth overall) and the Air Canada Centre in Toronto (third overall).

- The Red River Ex is an annual fair located near Assiniboia Downs horse race track

The Forks

The Forks, where the Red River and Assiniboine River meet, is Winnipeg's number one tourist attraction and brings locals and visitors alike to its shops, river walkways and festivals.[51] It is home to the Manitoba Theatre for Young People, Winnipeg International Children's Festival, a 30 000 square foot skate plaza, and an 8,500-square-foot (790 m2) 'bowl complex', and the Esplanade Riel bridge. It is the future home of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. In January 2008, the Guinness Book of World Records recognized The Forks as the home of the longest skating rink in the world.

Parks

Some of Winnipeg's large urban parks include Assiniboine Park, Central Park, Kings Park, Maple Grove Park, Kildonan Park, Kilcona Park, and St. Vital Park.

Assiniboine Park is home to a number of attractions including a minimum gauge railway, Assiniboine Valley Railway, the Assiniboine Park Zoo, a conservatory, the Leo Mol sculpture garden and the Assiniboine Forest.

Winnipeg is located only an hour or two of driving, from many large forests, lakes, beaches, parks; such as Whiteshell Provincial Park and Grand Beach Provincial Park.

Infrastructure

Health and medicine

- See also: List of hospitals in Winnipeg

Winnipeg's major hospitals include Concordia Hospital, Deer Lodge Centre, Grace Hospital, Health Sciences Centre, Misericordia Health Centre, Riverview Health Centre, Saint Boniface General Hospital, Seven Oaks General Hospital, Victoria General Hospital, and The Children's Hospital of Winnipeg.

The National Microbiology Laboratory is Canada's front line in its response to infectious diseases and one of only a handful of Biosafety level 4 microbiology laboratories in the world. The National Research Council also has the Institute for Biodiagnostics laboratory located in the downtown area.

Transportation

- See also: List of airports in the Winnipeg area

Winnipeg has had public transit since 1882, starting with horse-drawn streetcars. They were replaced by electric trolley cars which ran from 1891 to 1955, supplemented by motor buses since 1918, and electric trolleybuses from 1938 to 1970. Winnipeg Transit now operates entirely with diesel buses. For decades, the city has explored the idea of a rapid transit link, either bus or rail, from downtown to the University of Manitoba's suburban campus.

Winnipeg Bus Terminal, located in downtown Winnipeg, offers domestic and international service by Greyhound Canada, Jefferson Lines, Grey Goose Bus Lines, Beaver Bus Lines, and Brandon Air Shuttle. This terminal will move to a new location near the airport next year.

Winnipeg's airport, renamed Winnipeg James Armstrong Richardson International Airport in December 2006, is currently under redevelopment. A new terminal building is scheduled for completion by 2009, along with an office tower and a second hotel. The field was Canada's first international airport when it opened in 1928 as Stevenson Aerodrome.[52] The airport is the 7th busiest in Canada in terms of passenger traffic and, along with Winnipeg/St. Andrews Airport, is among the top 20 in terms of aircraft movements.

Winnipeg is a railway hub and is served by VIA Rail, Canadian National Railway (CN), Canadian Pacific Railway (CP), Burlington Northern Santa Fe Manitoba, and the Central Manitoba Railway (CEMR). It is the only city between Vancouver and Thunder Bay with direct U.S. connections.

The city is directly connected to the United States via Provincial Trunk Highway 75 (PTH 75) (a northern continuation of I-29 and US 75). The highway runs 107 km (66 mi) to Emerson, Manitoba, and is the busiest Canada – United States border crossing between Vancouver and the Great Lakes.[53] Much of the commercial traffic that crosses through Emerson, either originates from or is destined for Winnipeg. Inside the city, the highway is locally known as Pembina Highway (Route 42).

A four-lane highway, called the Perimeter Highway, built in 1969, serves as a by-pass, with at-grade intersections, and a few interchanges. It allows travellers on the Trans-Canada Highway to completely avoid the city. Some studies on the highway have given it the name "Disaster By Design".[54] Some of the city's major arterial roads include Route 155 (McGillivray Blvd), Route 165 (Bishop Grandin Blvd.), Route 17 (Chief Peguis Trail), and Route 90 (Brookside Blvd., Oak Point Hwy., King Edward St., Century St., Kenaston Blvd.).

Winnipeg has also embarked on an ambitious wayfinding program, erecting new signage at strategic downtown locations;[55] the intention is to make it easier for travellers, specifically tourists, to locate services and attractions.

Sports

Winnipeg has a long and storied sports history. It has been home to several professional hockey, football, baseball franchises, and dirt track stock car racing. There have also been many university and amateur athletes over the years that have left their mark.

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winnipeg Blue Bombers | Canadian Football League | Canad Inns Stadium | 1930 | 10 |

| Winnipeg Goldeyes | Northern League | Canwest Park | 1994 | 1 |

| Manitoba Moose | American Hockey League | MTS Centre | 1996 | 0 |

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winnipeg Saints | Manitoba Junior Hockey League | Dakota Community Centre | 4 | |

| Winnipeg South Blues | Manitoba Junior Hockey League | Century Arena | 9 | |

| Winnipeg Rifles | Canadian Junior Football League | Canad Inns Stadium | 2002 | 0 |

| Winnipeg Alliance FC | Canadian Major Indoor Soccer League | MTS Centre | 2007 | 0 |

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba Bisons(Mens Hockey) | Canadian Interuniversity Sport | Max Bell Centre | 1919 | 8 |

| Manitoba Bisons (Womens Hockey) | Canadian Interuniversity Sport | Max Bell Centre | 2000 | 0 |

| Manitoba Bisons (Football) | Canadian Interuniversity Sport | University Stadium | 1922 | 12 |

| Event Hosted | Years Hosted |

|---|---|

| Pan American Games | 1967, 1999 |

| World Junior Hockey Championships | 1999 |

| IIHF World Women Championships | 2007 |

| National Aboriginal Hockey Championship | 2009 |

Winnipeg is the only Canadian city to ever host the Pan American Games, and the second city in the world to host the event twice, once in 1967 and once in 1999.[42]

Education

- See also: List of schools of Winnipeg

Education is a responsibility of the provincial government in Canada.

In Manitoba, education is governed principally by The Public Schools Act and The Education Administration Act, as well as regulations made under both Acts. Rights and responsibilities of the Minister of Education, Citizenship and Youth and the rights and responsibilities of school boards, principals, teachers, parents and students are set out in the legislation.

There are two major universities, a community college, a private Mennonite university and a French college in Saint Boniface

The University of Manitoba is the largest university in the province of Manitoba, the most comprehensive and the only research-intensive post-secondary educational institution. It was founded in 1877, making it Western Canada’s first university. In a typical year, the university has an enrolment of 24,542 undergraduate students and 3,021 graduate students.

The University of Winnipeg received its charter in 1967 but its roots date back more than 130 years. The founding colleges were Manitoba College 1871, and Wesley College 1888, which merged to form United College in 1938. Until 2007, it was an undergraduate institution with a faculty of arts and science that offered some joint graduate studies programs. It now offers graduate programs exclusive to the university. In 2008, the university plans on creating a new faculty of business consisting of economics and business programs hived off from the faculty of arts.

Winnipeg is also home to numerous private schools, both religious and secular.

School divisionsThere are seven school divisions in Winnipeg:

|

Post-secondary InstitutionsThere are five post-secondary institutions in Winnipeg

|

Military

- See also: CFB Winnipeg

Canadian Forces Base Winnipeg, co-located at the airport, is home to many flight operations support divisions, as well as several training schools. It is also the headquarters of 1 Canadian Air Division and the Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) Region Headquarters. The base is supported by over 3,000 military personnel and civilian employees.

17 Wing of the Canadian Forces is based at CFB Winnipeg. The Wing comprises three squadrons and six schools. It also provides support to the Central Flying School. Excluding the three levels of government, 17 Wing is the fourth largest employer in the city. The Wing supports 113 units stretching from Thunder Bay, to the Saskatchewan/Alberta border and from the 49th parallel to the high Arctic. 17 Wing also acts as a deployed operating base for CF-18 Hornet fighter-bombers assigned to the Canadian NORAD Region.

Two squadrons based in the city are:

- 402 "City of Winnipeg" Squadron. This squadron flies the Canadian-designed and -produced de Havilland CT-142 Dash 8 navigation trainer.

- 435 "Chinthe" Transport and Rescue Squadron. This squadron flies the Lockheed CC-130 Hercules tanker/transport in the airlift search and rescue roles. In addition, 435 Squadron is the only Canadian Forces Air Command squadron equipped and trained to conduct air-to-air refueling of fighter aircraft.

Winnipeg is home to a number of reserve units:

- The Royal Winnipeg Rifles

- The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada infantry (along with the The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada Museum)

- 735 Communications Regiment

- 17 Service Battalion

- 17 (Winnipeg) Field Ambulance at Minto Armoury

- The Fort Garry Horse armoured reconnaissance regiment at McGregor Armoury

- HMCS Chippewa, original home to the Naval Museum of Manitoba

For many years, Winnipeg was the home of The Second Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, or 2 PPCLI. Initially, the battalion was based at the Fort Osborne Barracks near present day Osborne Village. They eventually moved to the Kapyong Barracks located in the River Heights/Tuxedo part of Winnipeg. Since 2004, the 550 men and women of the battalion have operated out of CFB Shilo near Brandon.

Law and government

- See also: List of mayors of Winnipeg

In 1869–70, Winnipeg was the site of the Red River Rebellion, a conflict between the local provisional government of Métis, led by Louis Riel, and the newcomers from eastern Canada. This rebellion led to Manitoba's entry into Confederation as Canada's fifth province in 1870, and on November 8, 1873, Winnipeg was incorporated as a city.

Municipal politics

Since 1992, the city of Winnipeg is represented by 15 city councillors and a mayor elected every three years. The present mayor, Sam Katz, was elected to office in 2004 and re-elected in 2006. Katz is Winnipeg's first Jewish mayor.

The city is a single-tier municipality, governed by a mayor-council system. The structure of the municipal government is set out by the province of Manitoba in the City of Winnipeg Act. The mayor is elected by direct popular vote to serve as the chief executive of the city. At Council meetings, the mayor has one of 16 votes. The City Council is a unicameral legislative body, representing geographical wards throughout the city.

Provincial politics

Winnipeg is represented by 31 provincial Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs)—25 of whom are members of the New Democratic Party, four are members of the Progressive Conservative Party, and two are members of the Liberal Party. In the provincial election in 2007, the NDP won two ridings from the Conservatives, rising from 23 to its present 25 seats in the city. All three leaders of the provincial parties represent Winnipeg in the legislature. Most Premiers of Manitoba are residents of Winnipeg.

Federal politics

Winnipeg is represented by eight Members of Parliament: four Conservatives, three New Democrats, and one Liberal. There are six Senators representing Manitoba in Ottawa. Only two list Winnipeg as the division they represent, although all of them were residents of Winnipeg when appointed to the Senate. The political affiliation in the Senate is three Liberals, two Conservatives, and one Independent.

Crime

In 2004, Winnipeg had the fourth-highest overall crime rate among Canadian Census Metropolitan Area cities listed, with 12,167 Criminal Code of Canada offences per 100,000 population; only Regina, Saskatoon, and Abbotsford had higher crime rates. Winnipeg had the highest rate among centres with populations greater than 500,000.[56] The crime rate was 50% higher than that of Calgary, and more than double the rate for Toronto.

Statistics Canada shows that in 2005, Manitoba had the highest decline of overall crime in Canada, at nearly 8%. Winnipeg dropped from having the highest rate of murder per capita in the country; that distinction went to Edmonton but ultimately returned to Winnipeg as of 2007. However, given the relatively small number of annual murders, even a small increase or decrease in the absolute numbers can translate into a large increase or decrease in the percentage rate. Manitoba did continue to lead all other provinces in auto thefts, almost all of it centred in Winnipeg.[57]

To combat auto theft, Manitoba Public Insurance (MPI) established financial incentives for motor vehicle owners to install ignition immobilisers in their vehicles, and now requires owners of high-risk vehicles to install them.[58]

Winnipeg is protected by the Winnipeg Police Service, which has over 1350 members.

Sister cities

This is a list of Winnipeg's sister cities and the date the agreement with each location was signed.

| Country | City | County/District/Region/State | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setagaya | Tokyo | October 5, 1970 | |

| Reykjavík | Iceland | September 7, 1971 | |

| Minneapolis | US | January 31, 1973 | |

| Lviv | Ukraine | November 26, 1973 | |

| Manila | Philippines | December 31, 1979 | |

| Taichung | Taiwan | April 2, 1982 | |

| Kuopio | Finland | June 11, 1982 | |

| Beersheba | Israel | May 15, 1984 | |

| Chengdu | China | February 24, 1988 | |

| Jinju | South Korea | April 1, 1992 | |

| San Nicolás de los Garza | Mexico | July 23, 1999 |

See also

- List of cities in Canada

- Valour Road

- Ukrainian Labour Temple

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population (2007-03-13). Retrieved on 2007-03-13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Winnipeg Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) with census subdivision (municipal) population breakdowns". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population (2007-03-13). Retrieved on 2007-03-13.

- ↑ Elevations and Distances in the United States USGS Survey

- ↑ City of Winnipeg website. "Winnipeg History". Retrieved on 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Statistics Canada. "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada and census subdivisions (municipalities) 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". Retrieved on 2008-04-16.

- ↑ Imperial Oil website. "Winnipeg History". Retrieved on 2008-10-07.

- ↑ World Lake Database. "Lake Winnipeg". Retrieved on 2007-01-05.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 CBC. "Winnipeg Skating". Retrieved on 2008-02-03.

- ↑ The Forks. "History". Retrieved on 2008-11-04.

- ↑ The Forks National Historic Site of Canada. "Parks Canada". Retrieved on 2007-01-05.

- ↑ "Who Named the North-Land?", Manitoba Free Press (August 19, 1876), pp. 3.

- ↑ Planetware. "Winnipeg, Manitoba". Retrieved on 2007-10-03.

- ↑ "Manitoba Royal Commission". American Review of Canadian Studies. Retrieved on 2007-07-04.

- ↑ "Hansard". Manitoba Legislature. Retrieved on 2007-08-08.

- ↑ "Urban Development Agreements". Western Economic Diversification Canada. Retrieved on 2008-04-29.

- ↑ "History". The Forks. Retrieved on 2009-05-03.

- ↑ Winnipeg.ca. "Winnipeg 2001 Census". Retrieved on 2008-11-28.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Canadian Climate Normals 1971-2000" (in English). Retrieved on 2008-09-01.

- ↑ veseys. "Manitoba". Retrieved on 2008-09-30.

- ↑ Environment Canada. "Winnipeg MB". Retrieved on 2008-11-27.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Environment Canada. "Winnipeg MB". Retrieved on 2008-09-13.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Environment Canada. "Winnipeg MB". Retrieved on 2008-09-13.

- ↑ Environment Canada. "Winnipeg MB". Retrieved on 2008-11-28.

- ↑ Microsoft ® Encarta ® Encyclopedia 2005 © 1993-2004 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. Retrieved on: October 18, 2008.

- ↑ The Weather Doctor. "Significant Weather Events Canada". Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Government of Manitoba. "Manitoba Weekly Vegetable Report". Retrieved on 2008-09-02.

- ↑ Environment Canada. "Canadian Climate Normals". Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

- ↑ "Winnipeg going Strong". Winnipeg Sun. Retrieved on 2007-09-14.

- ↑ "Winnipeg Advantages". Destination Winnipeg. Retrieved on 2007-06-09.

- ↑ "Bidders go Big". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Winnipeg City", in Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables, 2006 Census

- ↑ Winnipeg, Manitoba in 2006 Community Profiles

- ↑ Winnipeg, Manitoba” in 2006 Aboriginal Population Profile

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts, for census metropolitan areas (ALL), 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population (2007-03-13). Retrieved on 2007-03-13.

- ↑ "Community Profile of the City of Winnipeg". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population (2007-09-30). Retrieved on 2007-09-30.

- ↑ "Community Profile of Winnipeg CMA". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population (2007-09-30). Retrieved on 2007-09-30.

- ↑ Toronto

- ↑ 2001 Census Data, Languages. The City of Winnipeg. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ↑ "Community Profile of Winnipeg CMA". Statistics Canada, 2001 Census of Population (2007-09-30). Retrieved on 2007-09-30.

- ↑ City of Winnipeg. "Cultural Report" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-01-18.

- ↑ CTV. "Winnipeg Crowned Slurpee Capital". Retrieved on 2007-07-05.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 iaff.org. "Pan-am Games". Retrieved on 2007-10-03.

- ↑ Bob Buchanan. "The Murals of Winnipeg". Retrieved on 2007-08-22.

- ↑ CBC. "New Festival". Retrieved on 2007-07-31.

- ↑ Darryl Sterdan (2007). "jam! Showbiz, Album Review: Weakerthans". Retrieved on 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Wcities. "Manitoba Museum". Retrieved on 2008-01-18.

- ↑ Government of Canada. "Royal Winnipeg Ballet". Retrieved on 2008-07-23.

- ↑ Royal Winnipeg Ballet. "History". Retrieved on 2008-07-23.

- ↑ Canadian Encyclopedia. "Royal Winnipeg Ballet". Retrieved on 2008-07-23.

- ↑ Manitoba Theatre Centre. "About MTC". Retrieved on 2008-01-18.

- ↑ The Fairmont Winnipeg. "10 Best Sightseeing". Retrieved on 2008-01-18.

- ↑ Found Locally. "Transportation". Retrieved on 2007-07-17.

- ↑ NAIPN. "North American Inland Ports". Retrieved on 2007-02-24.

- ↑ fcpp.org. "WINNIPEG’S PERIMETER HIGHWAY: “DISASTER BY DESIGN”" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-11-08.

- ↑ Destination Winnipeg. "Wayfinding Signage System". Retrieved on 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Winnipeg Crime rate - Statistics Canada

- ↑ Neighbourhood Characteristics and the Distribution of Crime in Winnipeg - Statistics Canada, Extracted November 29, 2005

- ↑ Immobilizers to be mandatory on high-risk used cars in Manitoba CBC News, accessed 2007-10-03

Notations

- J. M. Bumsted, The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919: An Illustrated History 1994, 140 pp. heavily illus; ISBN 0-920486-40-1.

- Ramsay Cook; The Politics of John W. Dafoe and the Free Press (1963), 305 pp. B&W illustrations; ISBN 0802051197

- Grayson, J. P., and L. M. Grayson, "The Social Base of Interwar Political Unrest in Urban Alberta". Canadian Journal of Political Science, 7: 289–313 (1974)

- Hanlon, Christine; Edie, Barbara; Pendgracs, Doreen. Manitoba Book of Everything (2008) (ISBN 978-0-9784784-5-2)

- Kenneth McNaught; A Prophet in Politics: A Biography of J. S. Woodsworth (RICH: Reprints in Canadian History) (Paperback) Introduction Allen Mills. (2001), 304 pp.; ISBN 0802084273

- Norman Penner, ed., Winnipeg 1919: The Strikers' Own History of the Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto: 1973)

- K. W. Taylor; "Voting in Winnipeg During the Depression" Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology v 19 #2 1982. pp 222+

- Taylor, K. W., and Nelson Wiseman, "Class and Ethnic Voting in Winnipeg: The Case of 1941". Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 14: 174-87 1977

- Wiseman, Nelson and K. W. Taylor, "Ethnic vs Class Voting: the Case of Winnipeg, 1945". Canadian Journal of Political Science 7: 314-28 1974

- Wiseman, Nelson and K. W. Taylor, "Class and Ethnic Voting in Winnipeg During the Cold War". Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 16: 60–76 1979

External links

- Winnipeg.ca - Official Winnipeg website

- Destination Winnipeg economic and travel guide

- Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000: Winnipeg at Environment Canada

- Winnipedia

- Transit Riders' Union of Winnipeg

- Miles MacDonell Collegiate Alumni Association - Local Winnipeg History

- The Climate and Weather of Winnipeg, Manitoba - from Living in Canada

- Winnipeg and Manitoba stories- 250 stories about Winnipeg and Manitoba History

|

Lake Manitoba Stonewall |

Gimli | Lake Winnipeg Selkirk |

|

|||

| Portage la Prairie Brandon |

Kenora, Ontario Thunder Bay, Ontario |

||||||

| Carman Morden Winkler |

Grand Forks, ND, USA Fargo, North Daktoa, USA |

Steinbach Lake of the Woods |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||