William Faulkner

| William Faulkner | |

|---|---|

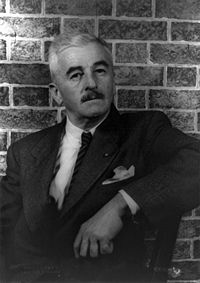

Faulkner in 1954, photograph by Carl Van Vechten |

|

| Born | William Cuthbert Falkner September 25, 1897 New Albany, Mississippi |

| Died | July 6, 1962 (aged 64) Byhalia, Mississippi |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer |

| Genres | Southern Gothic |

| Literary movement | Modernism, Stream of consciousness |

| Notable award(s) | Nobel Prize in Literature, 1949 |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

William Faulkner (September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was a Nobel Prize-winning American author. One of the most influential writers of the 20th century, his reputation is based on his novels, novellas and short stories. However, he was also a published poet and an occasional screenwriter.

Most of Faulkner's works are set in his native state of Mississippi, and he is considered one of the most important Southern writers, along with Mark Twain, Robert Penn Warren, Flannery O'Connor, Truman Capote, Eudora Welty, and Tennessee Williams.

While his work was published regularly starting in the mid 1920s, Faulkner was relatively unknown before receiving the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature. He is now deemed among the greatest American writers of all time.[1]

Contents |

Early life

He was born William Cuthbert Falkner AKA Gibby in New Albany, Mississippi, the eldest son of Murry Cuthbert Falkner (August 17, 1870–August 7, 1932) and Maud Butler (November 27, 1871–October 16, 1960). His brothers were Murry Charles "Jack" Falkner (June 26, 1899–December 24, 1975); author John Faulkner (September 24, 1901–March 28, 1963); and Dean Swift Falkner (August 15, 1907–November 10, 1935).

William was raised in and heavily influenced by the state of Mississippi, as well as by the history and culture of the South as a whole. When he was four years old, his entire family moved to the nearby town of Oxford, where he lived on and off for the rest of his life. Oxford is the model for the town of "Jefferson" in his fiction, and Lafayette County, Mississippi, which contains the town of Oxford, is the model for his fictional Yoknapatawpha County. Faulkner's great-grandfather, William Clark Falkner, was an important figure in northern Mississippi who served as a colonel in the Confederate Army, founded a railroad, and gave his name to the town of Falkner in nearby Tippah County. He also wrote several novels and other works, establishing a literary tradition in the family. Colonel Falkner served as the model for Colonel John Sartoris in his great-grandson's writing.

The older Falkner was greatly influenced by the history of his family and the region in which they lived. Mississippi marked his sense of humor, his sense of the tragic position of blacks and whites, his characterization of Southern characters and timeless themes, including fiercely intelligent people dwelling behind the façades of good old boys and simpletons. Unable to join the United States Army because of his height, (he was 5' 5½"), Faulkner first joined the Canadian and then the British Royal Air Force, yet did not see any World War I wartime action.

The definitive reason for Faulkner's change in the spelling of his last name is still unknown. Faulkner himself may have made the change in 1918 upon joining the Air Force or, according to one story, a careless typesetter simply made an error. When the misprint appeared on the title page of Faulkner's first book and the author was asked about it, he supposedly replied, "Either way suits me."[2]

Although Faulkner is heavily identified with Mississippi, he was living in New Orleans in 1925 when he wrote his first novel, Soldiers' Pay, after being influenced by Sherwood Anderson to try fiction. The small house at 624 Pirate's Alley, just around the corner from St. Louis Cathedral, is now the premises of Faulkner House Books, and also serves as the headquarters of the Pirate's Alley Faulkner Society.

Faulkner served as Writer-in-Residence at the University of Virginia from 1957 until his death at Wright's Sanitorium in Byhalia, Mississippi of a heart attack at the age of 64.

In Hollywood

In the early 1940s, Howard Hawks invited Faulkner to come to Hollywood to become a screenwriter for the films Hawks was directing. Faulkner happily accepted because he badly needed the money, and Hollywood paid well. Thus Faulkner contributed to the scripts for the films Hawks made from Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep and Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not. Faulkner became good friends with director Howard Hawks, the screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides, and the actors Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

An apocryphal story regarding Faulkner during his Hollywood years found him with a case of writer's block at the studio. He told Hawks he was having a hard time concentrating and would like to write at home. Hawks was agreeable, and Faulkner left. Several days passed, with no word from the writer. Hawks telephoned Faulkner's hotel and found that Faulkner had checked out several days earlier. It seems Faulkner had spoken quite literally, and had returned home to Mississippi to finish the screenplay.

Personal

Faulkner married Estelle Oldham in June 1929 at College Hill Presbyterian Church just outside of Oxford, Mississippi. They honeymooned on the Mississippi Gulf Coast at Pascagoula, then returned to Oxford, first living with relatives while they searched for a home of their own to purchase. In 1930 Faulkner purchased the antebellum home Rowan Oak, known at that time as "The Bailey Place." He and his family lived there until his daughter Jill, after her mother's death, sold the property to the University of Mississippi in 1972. The house and furnishings are maintained much as they were in Faulkner's day. Faulkner's scribblings are still preserved on the wall there, including the day-by-day outline covering an entire week that he wrote out on the walls of his small study to help him keep track of the plot twists in the novel A Fable.

Faulkner accomplished what he did despite a lifelong serious drinking problem. As he stated on several occasions, and as was witnessed by members of his family, the press, and friends at various periods over the course of his career, he did not drink while writing, nor did he believe that alcohol helped to fuel the creative process. It is now widely believed that Faulkner used alcohol as an "escape valve" from the day-to-day pressures of his regular life, including his financial straits, rather than the more romantic vision of a brilliant writer who needed alcohol to pursue his craft.

Faulkner is known to have had two extramarital affairs. One was with Howard Hawks's secretary and script-girl, Meta Carpenter. The other, lasting from 1949 to 1953, was with a young writer, Joan Williams, who considered him her mentor. She made her relationship with Faulkner the subject of her 1971 novel The Wintering.

Faulkner also had a romance with Jean Stein, an editor, author, and daughter of movie mogul Jules Stein. [1]

Writing

From the early 1920s to the outbreak of WWII, when Faulkner left for Hollywood, he published 13 novels and numerous short stories, the body of work that grounds his reputation and for which he was awarded Nobel Prize at the age of 52. This prodigious output, mainly driven by an obscure writer's need for money, includes his most celebrated novels such as The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), and Absalom, Absalom! (1936). Faulkner was also a prolific writer of short stories. His first short story collection, These 13 (1932), includes many of his most acclaimed (and most frequently anthologized) stories, including "A Rose for Emily," "Red Leaves", "That Evening Sun," and "Dry September."

Faulkner set many of his short stories and novels in Yoknapatawpha County—based on, and nearly geographically identical to, Lafayette County, of which his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi is the county seat. Yoknapatawpha was Faulkner's "postage stamp," and the bulk of work that it represents is widely considered by critics to amount to one of the most monumental fictional creations in the history of literature.[2] Three novels, The Hamlet, The Town, and The Mansion, known collectively as the Snopes Trilogy document the town of Jefferson and its environs as an extended family headed by Flem Snopes insinuates itself into the lives and psyches of the general populace. It is a stage wherein rapaciousness and decay come to the fore in a world where such realities were always present, but never so compartmentalized and well defined; their sources never so easily identifiable.

Additional works include Sanctuary (1931), a sensationalist "pulp fiction"-styled novel, characterized by André Malraux as "the intrusion of Greek tragedy into the detective story." Its themes of evil and corruption, bearing Southern Gothic tones, resonate to this day. Requiem for a Nun (1951), a play/novel sequel to Sanctuary, is the only play that Faulkner published, except for his The Marionettes, which he essentially self-published -- in a few hand-written copies -- as a young man.

Faulkner is known for an experimental style with meticulous attention to diction and cadence. In contrast to the minimalist understatement of his peer Ernest Hemingway, Faulkner made frequent use of "stream of consciousness" in his writing, and wrote often highly emotional, subtle, cerebral, complex, and sometimes Gothic or grotesque stories of a wide variety of characters—ranging from former slaves or descendents of slaves, to poor white, agrarian, or working-class Southerners, to Southern aristocrats.

In an interview with The Paris Review in 1956, Faulkner remarked, "Let the writer take up surgery or bricklaying if he is interested in technique. There is no mechanical way to get the writing done, no shortcut. The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory. Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error. The good artist believes that nobody is good enough to give him advice. He has supreme vanity. No matter how much he admires the old writer, he wants to beat him." Another esteemed Southern writer, Flannery O'Connor, stated that, "The presence alone of Faulkner in our midst makes a great difference in what the writer can and cannot permit himself to do. Nobody wants his mule and wagon stalled on the same track the Dixie Limited is roaring down."

Faulkner also wrote two volumes of poetry which were published in small printings, The Marble Faun (1924) and A Green Bough (1933), and a collection of crime-fiction short stories, Knight's Gambit.

Awards

Faulkner received the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature for "his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel." He donated a portion of his Nobel winnings "to establish a fund to support and encourage new fiction writers," eventually resulting in the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. He donated another portion to a local Oxford bank to establish an account to provide scholarship funds to help educate African-American education majors at nearby Rust College in Holly Springs, Mississippi.

Faulkner won two Pulitzer Prizes for what are considered as his "minor" novels: his 1954 novel A Fable, which took the Pulitzer in 1955, and the 1962 novel, The Reivers, which was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer in 1963. He also won two National Book Awards, first for his Collected Stories in 1951 and once again for his novel A Fable in 1955.

In 1946, Faulkner was one of three finalists for the first Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine Award. He came in second to Manly Wade Wellman.[3]

On August 3, 1987, the United States Postal Service issued a 22 cent postage stamp in his honor.[4]

See also

- Adult Swim, Cartoon Network

Adult Swim, for the second to last week of November, 2008, showed Faulkner's name, date of birth, and date of death as a tribute. Adult Swim does this regularly out of respect for some influential people and possibly to encourage the viewers to research the person in the tribute if they aren't already familiar with them.

Selected writings

Novels

- Soldiers' Pay (1926)

- Mosquitoes (1927)

- Sartoris/Flags in the Dust (1929/1973)

- The Sound and the Fury (1929)

- As I Lay Dying (1930)

- Sanctuary (1931)

- Light in August (1932)

- Pylon (1935)

- Absalom, Absalom! (1936)

- The Unvanquished (1938)

- If I Forget Thee Jerusalem (The Wild Palms/Old Man) (1939)

- The Hamlet (1940)

- Go Down, Moses (1942). Episodic novel made up of rewritten previous published short stories.

- Intruder in the Dust (1948)

- Requiem for a Nun (1951)

- A Fable (1954)

- The Town (1957)

- The Mansion (1959)

- The Reivers (1962)

Short stories

|

|

|

Poetry

- Vision in Spring (1921)

- The Marble Faun (1924)

- A Green Bough (1933)

- This Earth, a Poem (1932)

- Mississippi Poems (1979)

- Helen, a Courtship and Mississippi Poems (1981).

Discography

- The William Faulkner Audio Collection. Caedmon, 2003. Five hours on five discs includes Faulkner reading his 1949 Nobel Prize acceptance speech and excerpts from As I Lay Dying, The Old Man and A Fable, plus readings by Debra Winger ("A Rose for Emily", "Barn Burning"), Keith Carradine ("Spotted Horses") and Arliss Howard ("That Evening Sun", "Wash"). Winner of AudioFile Earphones Award.

- William Faulkner Reads: The Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, Selections from As I Lay Dying, A Fable, The Old Man. Caedmon/Harper Audio, 1992. Cassette. ISBN 1-55994-572-9

- William Faulkner Reads from His Work. Arcady Series, MGM E3617 ARC, 1957. Faulkner reads from The Sound and The Fury (side one) and Light in August (side two). Produced by Jean Stein, who also did the liner notes with Edward Cole. Cover photograph by Robert Capa (Magnum).

Listen to

References

- ↑ New York Times, October 12, 2006:

- ↑ Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981: 63–64. ISBN 086576008X

- ↑ Oregon Lit Rev website

- ↑ Scott catalog # 2350.

- William Faulkner: Novels 1930-1935 (Joseph Blotner and Noel Polk, ed.) (Library of America, 1985) ISBN 978-0-94045026-4

- William Faulkner: Novels 1936-1940 (Joseph Blotner and Noel Polk, eds.) (Library of America, 1990) ISBN 978-0-94045055-4

- William Faulkner: Novels 1942-1954 (Joseph Blotner and Noel Polk, eds.) (Library of America, 1994) ISBN 978-0-94045085-1

- William Faulkner: Novels 1957-1962 (Noel Polk, ed., with notes by Joseph Blotner) (Library of America, 1999) ISBN 978-1-88301169-7

- William Faulkner: Novels 1926-1929 (Joseph Blotner and Noel Polk, eds.) (Library of America, 2006) ISBN 978-1-93108289-1

Secondary Literature:

- Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. New York: Random House, 1974. 2 vols.

- Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. New York: Random House, 1984.

- Sensibar, Judith L. The Origins of Faulkner's Art. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982.

- Sensibar, Judith L. Faulkner and Love: The Women Who Shaped His Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Margaret Kerr, Elizabeth, and Kerr, Michael M. William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha: A Kind of Keystone in the Universe. Fordham Univ Press, 1985 ISBN 0823211355, 9780823211357

- Fowler, Doreen, Abadie, Ann. Faulkner and Popular Culture: Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1990 ISBN 0878054340, 9780878054343

External links

- William Faulkner on the Web

- Faulkner literary criticism

- The Faulkner Journal

- William Faulkner at the Mississippi Writers Project

- Faulkner Postmaster Letters (MUM00165) owned by the University of Mississippi, Archives and Special Collections.

- Faulkner/Rowan Oak Advisory Committee Collection (MUM00173) at the University of Mississippi.

- The Paris Review Interview

- Nobel Prize in Literature 1949 Acceptance Speech (text and audio)

- Machine translation or Faulkner?

- William Faulkner Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- [3]

- William Faulkner: The Faded Rose of Emily

- Works by or about William Faulkner in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

|

|||||

|

||||||||