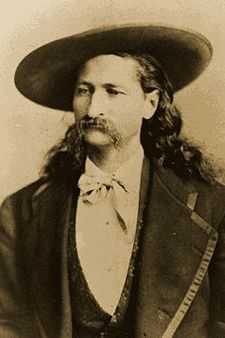

Wild Bill Hickok

| Wild Bill Hickok | |

|

|

| Born | James Butler Hickok May 27, 1837 Troy Grove, Illinois, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | August 2, 1876 (aged 39) Deadwood, Dakota Territory, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Murdered (shot in the back of the head) by Jack McCall |

| Resting place | Mount Moriah Cemetery |

| Occupation | Abolitionist, facilitator of the Underground Railroad, Lawman, Gunfighter, Gambler |

James Butler Hickok (May 27, 1837 – August 2, 1876), better known as Wild Bill Hickok, was a figure in the American Old West. His skills as a gunfighter and scout, along with his reputation as a lawman, provided the basis for his fame, although some of his exploits are fictionalized. His nickname of Wild Bill has inspired similar nicknames for men named William (even though that was not Hickok's name) who were known for their daring in various fields. Hickok's horse was called Black Nell, and he owned two Colt 1851 Navy Revolvers.

Hickok came to the West as a stagecoach driver, then became a lawman in the frontier territories of Kansas and Nebraska. He fought in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and gained publicity after the war as a scout, marksman, and professional gambler. Between his law-enforcement duties and gambling, which easily overlapped, Hickok was involved in several notable shootouts, and was ultimately killed while playing poker in a Dakota Territory saloon.

Contents |

Life and career

Early life

Wild Bill Hickok was born in Homer, Illinois (name later changed to Troy Grove, Illinois) on May 27, 1837. His birthplace is now the Wild Bill Hickok Memorial, a listed historic site under the supervision of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. While he was growing up, his father's farm was one of the stops on the Underground Railroad, and he learned his shooting skills protecting the farm with his father from slave catchers. Hickok was a good shot from a very young age.

In 1855, at the age of 18, Hickok moved to Kansas Territory following a fight with Charles Hudson, which resulted in both falling into a canal. Mistakenly thinking he had killed Hudson, Hickok fled and joined General Jim Lane's vigilante Free State Army ("The Red Legs") where he met then 12 year old William Cody, later to be known as "Buffalo Bill", who at that time was a scout for Johnston's Army.[1] At 19 Hickok was elected constable of Monticello Township.

Due to his "sweeping nose and protruding upper lip", Hickok was nicknamed "Duck Bill".[2] In 1861, after growing a mustache following the infamous McCanles incident, and not without some encouragement from himself, he was to become known by the nickname he is most famous for, "Wild Bill".[3]

Constable

In 1857, Hickok claimed a 160-acre (65 ha) tract in Johnson County, Kansas (in what is now the city of Lenexa),[4] where, on March 22 in 1858, he was elected as one of the first four constables of Monticello Township, Kansas. In 1859 he joined the Russell, Waddell, and Majors freight company as a driver. The following year he was badly injured by a bear and sent to the Rock Creek Station in Nebraska (which the company had recently purchased from David McCanles) to work as a stable hand while he recovered. In 1861 he was involved in a deadly shoot-out with the McCanles Gang at the Rock Creek Station after 40 year old David McCanles, his 12-year-old son (William) Monroe McCanles and two farmhands, James Woods and James Gordon, called at the station's office to demand payment of an overdue second installment on the property, an event that is still the subject of much debate. Hickok and his accomplices, the station manager Horace Wellman, his wife and an employee J.W. Brink were tried but judged to have acted in self-defense.[1] According to Joseph G. Rosa, a Hickok biographer, the shot that felled the elder McCanles came from inside the house. It remains unknown who actually fired it. Rosa conjectures that Wellman had far more of a motive to kill McCanles, a belief supported by McCanles' son's own account. There were also women in the house, conceivably armed with shotguns. McCanles was the first man Hickok was reputed to have killed in a fight. On several later occasions, Hickok was to confront and kill several men while fighting alone.[5]

Civil War and scouting

When the Civil War began, Hickok joined the Union forces and served in the west, mostly in Kansas and Missouri. He earned a reputation as a skilled scout. After the war, Hickok became a scout for the U. S. Army and later was a professional gambler. He served for a time as a United States Marshal. In 1867, his fame increased from an interview by Henry Morton Stanley.

During the Civil War, Buffalo Bill Cody served as a scout with Robert Denbow, David L. Payne, and Hickok. The men formed a friendship that would last decades. After the war, the four men, Payne, Cody, Hickok, and Denbow engaged in buffalo hunting. When Payne moved to Wichita, Kansas in 1870, Denbow joined him there while Hickok served as sheriff of Hays, Kansas.

In 1873 Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro invited Hickok to join them in a new play called Scouts of the Plains after their earlier success.[6] Hickok and Texas Jack eventually left the show, before Cody formed his Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1882.[7]

Lawman and gunfighter notoriety

On July 21, 1865, in the town square of Springfield, Hickok killed Davis Tutt, Jr. in a "quick draw" duel. Fiction later typified this kind of gunfight, but Hickok's is in fact the first one on record that fits the portrayal.[8]

Hickok first met former Confederate Army soldier Davis Tutt in early 1865, while both were gambling in Springfield, Missouri. Hickok would often borrow money from Tutt during that time. Although originally good friends,[9] they eventually fell out over a woman, and it was rumored that Hickok once had an affair with Tutt's sister, perhaps fathering a child and likely exacerbated by the fact there was a long standing dispute over Hickok's girlfriend Susannah Moore. Hickok refused to play cards with Tutt, who retaliated by financing other players in an attempt to bankrupt him.

According to the accepted account, the dispute came to a head when Tutt was coaching an opponent of Hickok's during a card game. Hickok was on a winning streak and, frustrated, Tutt requested he repay a $40 loan which Hickok did. Tutt then demanded another $35 owed from a previous card game. Hickok refused as he had "a memorandum" proving it to be $25. Tutt then took Hickok's watch, which was lying on the table, as collateral for the $35 at which Hickok warned him not to wear it or he would shoot him. Next day, at 6 p.m. Tutt entered the town square wearing the watch prominently. Hickok arrived on the other side of the square and the two men fired almost simultaneously. Tutt's shot missed but Hickok's didn't and after stumbling, Tutt collapsed and died.[10]

Hickok was arrested for murder two days later; however, the charge was later reduced to manslaughter. He was released on $2,000 bail and stood trial on August 3, 1865. At the end of the trial judge Sempronius Boyd gave the jury two contradictory instructions. He first instructed the jury that a conviction was its only option under the law.[11] He then instructed them that they could apply the unwritten law of the "fair fight" and acquit.[12] The jury voted for acquittal, a verdict that was not popular at the time.[13]

Several weeks later Hickok was interviewed by Colonel George Ward Nichols and the interview was published in Harpers New Monthly Magazine. Using the name "Wild Bill Hickok", the article recounted the hundreds of men Hickok personally killed, and other exaggerated exploits. The article was controversial wherever Hickok was known and led to several frontier newspapers writing rebuttals.

In September 1865, Hickok came in second in the election for City Marshal of Springfield. Leaving Springfield he was recommended for the position of Deputy United States Marshal at Fort Riley Kansas. At this time the Western Plains were involved in Native American wars and Hickok also served as a scout for George A. Custer's 7th Cavalry.[1]

In 1867 Hickok took a break from the west and moved to Niagara Falls where he tried his hand at acting in a stage play called "The Daring Buffalo Chases of the Plains".[14] He proved to be a terrible actor and returned west, where in 1868 he ran for sheriff in Ellsworth County, Kansas, but was defeated by former soldier E.W. Kingsbury, but was elected sheriff and city marshal of Ellis County, Kansas on August 23, 1869.[15] In his first month in Hays, Kansas he killed two men in gunfights. The first was Bill Mulvey who "got the drop" on Hickok. Hickok looked past him and yelled "Don't shoot him boys" which was enough distraction to win him the fight.[1] The second was cowboy Samuel Strawhun, who drew his gun on Hickok after the latter had been called to a saloon where Strawhun was causing a disturbance.[16]

On July 17, 1870, also in Hays, he was involved in a gunfight with disorderly soldiers of the 7th US Cavalry, wounding one and mortally wounding another, John Kyle[17]. He later failed to win reelection. On April 15 1871, Hickok became marshal of Abilene, Kansas, taking over for former marshal Tom "Bear River" Smith, who had been killed on November 2, 1870.[18] The outlaw John Wesley Hardin, who was in Abilene in 1871, was befriended by Hickok. In his 1895 autobiography (published after his own death, and 19 years after Hickok's) Hardin claimed to have disarmed Hickok using the famous Road agent's spin during a failed attempt to arrest him for wearing his pistols in a saloon, and that Hickok at the time had two guns drawn and pointed at him. This story is considered to be apocryphal, or at the very least an exaggeration, as Hardin claimed this at a time when Hickok couldn't defend himself, and Hardin was and is considered to be boastful, a liar, a psychopath; he in turn idealized Hickok and self-identified himself with Wild Bill.[1][19] It is also recorded that when Hardin's cousin Mannen Clements was jailed for the killing of two cowboys, Hickok at Hardin's request arranged for his escape.[20]

While working in Abilene, Hickok and Phil Coe, a saloon owner, had an ongoing dispute that later resulted in a shootout. Coe had been the business partner of known gunman Ben Thompson, with whom he co-owned the Bulls Head Saloon. On October 5, 1871, Hickok was standing off a crowd during a street brawl, during which time Coe fired two shots and Hickok ordered him to be arrested for firing a pistol within the city limits. Coe explained he was shooting at a stray dog[21] but suddenly turned his gun on Hickok who fired first and killed Coe. Hickok caught the glimpse of movement of someone running toward him and quickly fired two shots in reaction, accidentally shooting and killing Abilene Special Deputy Marshal Mike Williams,[22] who was coming to his aid, an event that haunted Hickok for the remainder of his life.[23] There is another account of the Coe shootout. Theophilus Little, a mayor of Abilene and owner of the town's lumberyard, wrote a notebook recording his time in Abilene which was recently given to the Abilene Historical Society. Written in 1911, in it he details his admiration of Hickok and includes a paragraph on the shooting that differs considerably from the accepted account.[24]

"-"Phil" Coe was from Texas, ran the "Bull’s Head" a saloon and gambling den, sold whiskey and men’s souls. A vile a character as I ever met for some cause Wild Bill incurred Coe’s hatred and he vowed to secure the death of the Marshall. Not having the courage to do it himself, he one day filled about 200 cowboys with whiskey intending to get them into trouble with Wild Bill, hoping that they would get to shooting and in the melee shoot the marshal. But Coe "reckoned without his host." Wild Bill had learned of the scheme and cornered Coe, had his two pistols drawn on Coe. Just as he pulled the trigger one of the policemen rushed around the corner between Coe and the pistols and both balls entered his body, killing him instantly. in an instant, he pulled the triggers again sending two bullets into Coe's abdomen (Coe lived a day or two) and whirling with his two guns drawn on the drunken crowd of cowboys, "and now do any of you fellows want the rest of these bullets". Not a word was uttered."

Hickok's retort to Coe, who supposedly stated he could "kill a crow on the wing", is one of the West's most famous sayings (though possibly apocryphal): "Did the crow have a pistol? Was he shooting back? I will be." However, due to his having accidentally killed deputy Mike Williams, Hickok was relieved of his duties as marshal less than two months later.

Hickok's favorite guns were a pair of cap and ball Colt 1851 .36 Navy Model handguns which he wore until his death. These were silver-plated with ivory handles and were engraved: "J.B. Hickock 1869"(sic) He was presented the guns in 1869 by Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts for his services as the Senator's scout on a hunting trip. However, Hickok exchanged them for larger caliber weapons when expecting a fight. For the Tutt gunfight he used a pair of .44 Colt Dragoons and in the Coe shooting used .44 1860 Army Colts. He wore his revolvers backwards at his hips and never used holsters; he wore them in a red sash when wearing buckskins or in a belt when wearing "city" clothes. He drew them using a "reverse", or "twist", draw.

In 1876 Hickok was diagnosed by a doctor in Kansas City, Missouri, with glaucoma and opthalmia, a condition that it was widely rumored at the time by Hickok's detractors to be the result of various sexually transmitted diseases. In truth, he seems to had been afflicted with trachoma, a common vision disorder of the time. It was apparent that his markmanship and health had been suffering for some time as despite earning a good income from gambling and displays of showmanship only a few years earlier, by this time he had been arrested several times for vagrancy. On March 5, 1876 Hickok married Agnes Thatcher Lake, a 50-year-old circus proprietor. Calamity Jane claimed in her autobiography that she was married to Hickok and had divorced him so he could be free to marry Agnes Lake. Hickok soon left his new bride to seek his fortune in the gold fields of South Dakota.

Shortly before Hickok's death, he wrote a letter to his new wife, Agnes Lake Thatcher, which reads in part: "Agnes Darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife—Agnes—and with wishes even for my enemies I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore".

Death

On August 2, 1876, while playing poker at Nuttal & Mann's Saloon No. 10 in Deadwood, in the Black Hills, Dakota Territory, Hickok could not find an empty seat in the corner, where he always sat in order to protect himself against sneak attacks from behind, and instead sat with his back to one door and facing another. His paranoia was prescient: he was shot in the back of the head with a .45-caliber revolver by Jack McCall. Legend has it that Hickok was playing poker when he was shot, was holding a pair of aces, a pair of eights, and a queen. The fifth card is debated, or, as some say, had not yet been dealt. "Aces and eights" thus is known as the "Dead Man's Hand".[25] In 1979 Hickok was inducted into the Poker Hall of Fame.

The motive for the killing is still debated. McCall may have been paid for the deed, or it may have been the result of a recent dispute between the two. Most likely McCall became enraged over what he perceived as a condescending offer from Hickok to let him have enough money for breakfast after he had lost all his money playing poker the previous day. McCall claimed at the resulting two-hour trial, by a miners jury, an ad hoc local group of assembled miners and businessmen, that he was avenging Hickok's earlier slaying of his brother which was later found untrue.[26] McCall was acquitted of the murder, resulting in the Black Hills Pioneer editorializing:

- "Should it ever be our misfortune to kill a man ... we would simply ask that our trial may take place in some of the mining camps of these hills"

McCall was subsequently rearrested after bragging about his deed, and a new trial was held. The authorities did not consider this to be double jeopardy because at the time Deadwood was not recognized by the U.S. as a legitimately incorporated town because it was in Indian Country and the jury was irregular. The new trial was held in Yankton, capital of the territory. Hickok's brother, Lorenzo Butler Hickok, traveled from Illinois to attend the retrial and spoke to McCall after the trial, noting he showed no remorse. This time McCall was found guilty. Reporter Leander Richardson interviewed Hickok shortly before his death and helped bury him. Richardson wrote of the encounter for the April 1877 issue of Scribner's Monthly in which he mentions McCall's second trial.[27]

"As I write the closing lines of this brief sketch, word reaches me that the slayer of Wild Bill has been re-arrested by the United State authorities, and after trial has been sentenced to death for willful murder. He is now at Yankton, D.T. awaiting execution. At the trial it was proved that the murderer was hired to do his work by gamblers[28] who feared the time when better citizens should appoint Bill the champion of law and order--a post which he formerly sustained in Kansas border life, with credit to his manhood and his courage."

McCall was hanged on March 1, 1877 and buried in the Catholic cemetery. When the cemetery was moved in 1881 his body was exhumed and found to have the noose still around his neck. The killing of Wild Bill and the capture of Jack McCall is re-enacted every evening (in summer) in Deadwood.[29]

Funeral and burial

Charlie Utter, Hickok's friend and companion, claimed Hickok's body and placed a notice in the local newspaper, the Black Hills Pioneer, which read:

"Died in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2, 1876, from the effects of a pistol shot, J. B. Hickok (Wild Bill) formerly of Cheyenne, Wyoming. Funeral services will be held at Charlie Utter's Camp, on Thursday afternoon, August 3, 1876, at 3 o'clock P. M. All are respectfully invited to attend."

Almost the entire town attended the funeral, and Utter had Hickok buried with a wooden grave marker reading:

"Wild Bill, J. B. Hickok killed by the assassin Jack McCall in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2, 1876. Pard, we will meet again in the happy hunting ground to part no more. Good bye, Colorado Charlie, C. H. Utter."

Hickok was originally buried in the Ingelside Cemetery, Deadwood's original graveyard. The graveyard filled quickly and was in an area that could be better used for the constant influx of settlers to live on, so all the bodies there were moved up the hill to the Mount Moriah Cemetery in the 1880s.

Hickok is currently interred in a ten-foot (3 m) square plot at the Mount Moriah Cemetery, surrounded by a cast-iron fence with a U.S. flag flying nearby. A monument has since been built there. In accordance with her dying wish, Martha Jane Cannary, known popularly as Calamity Jane, was buried next to him. Potato Creek Johnny, a local Deadwood Celebrity from the late 1800s and early 1900s is also buried next to Wild Bill.

"Dime novel" fame

It is difficult to separate the truth from fiction about Hickok, the first "dime novel" hero of the western era, in many ways one of the first comic book heroes, keeping company with another who achieved part of his fame in such a way, frontiersman Davy Crockett. In the dime-store novels, exploits of Hickok were presented in heroic form, making him seem larger than life. In truth, most of the stories were greatly exaggerated or fabricated by both the writers and himself.

Hickok told the writers that he had killed over 100 men. This number is doubtful, and it is more likely that his total killings were about 20 or a few more. He also would tell tourists various exaggerated exploits of his, usually leaving himself unarmed with no manner of escape, and then stop talking. When someone would inevitably ask what he did then, he claimed "I was surrounded. What could I do? They killed me."

Hickok was a fearless and deadly fighting man. Versatile with a rifle, revolver, or knife. His story of fighting a grizzly bear, which he claims mistook him for food because of his greasy buckskins, personified a man who feared nothing. According to Wild Bill, he killed the bear with a Bowie knife after emptying his pistols into the bear. He also cut off the bear's testicles and put them in a coffee can. That story is also thought to be an exaggeration.

Media

Television

- Portrayed by Guy Madison in the 1951-58 series The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok.

- the same cast also appeared in the Mutual Broadcasting radio show "The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok" from 1 Apr 1951 thru 31 Dec 1954, a total of 271 half hour radio programs.

- Played by Lloyd Bridges in a 1964 episode of the anthology The Great Adventure.

- Portrayed by Josh Brolin in the 1989-92 series The Young Riders.

- Featured in the 1995 series Legend, episode 1.06 "The Life, Death and Life of Wild Bill Hickok". The episode portrays his death factually but then goes on to show that he faked his own death (wearing a sort of bullet-proof vest), so that he could retire peacefully.

- Dramatized in the HBO series Deadwood, in which he is portrayed by Keith Carradine.

- In the 1995 made-for-TV film Buffalo Girls based on the best-selling novel of the same name by Larry McMurtry, he was played by actor Sam Elliott with Anjelica Huston as Calamity Jane. The film touched briefly on Hickok's days as an Army scout and gambler, and his death was portrayed factually. However, the film (as does the book on which it is based) gives credence to the legend that Calamity Jane had a daughter by him, born posthumously.

- Played by Sam Shepard in the 1999 movie Purgatory, a made-for-TV movie on TNT

- Histeria! featured Hickok in the episode "North America"; he appears in a sketch where Lydia Karaoke hosts a game show in which her contestants must guess Hickok's occupation. However, the contestants (Pepper Mills, Lucky Bob, and Toast) are unable to guess the correct answer, despite Karaoke's continuous hints.

Movies

- Played by William S. Hart in the 1923 film Wild Bill Hickok

- Played by Gary Cooper in the 1936 film The Plainsman, featuring Jean Arthur as Calamity Jane and directed by Cecil B. DeMille

- Played by Wild Bill Elliott in the 1938 serial The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok

- Played by Roy Rogers in the 1940 film The Young Hickok, directed by Joseph Kane

- Played by Howard Keel in the 1953 film Calamity Jane

- Played by Robert Culp in the 1963 film The Raiders, directed by Hershel Daugherty

- Portrayed by Jeff Corey in the 1970 Dustin Hoffman movie Little Big Man

- Portrayed by Charles Bronson in the 1977 movie The White Buffalo

- Portrayed by Richard Farnsworth in the 1981 movie The Legend of the Lone Ranger

- Portrayed by Jeff Bridges in the 1995 movie Wild Bill

Novels

- The Memoirs of Wild Bill Hickok, Richard Matheson, ISBN 0-515-11780-3

- Deadwood, Pete Dexter - 1986

- And Not to Yield, Randy Lee Eickoff

- A Breed Apart Max Evans

- The White Buffalo, Richard Sale

- Little Big Man, Thomas Berger - 1964

- The Return of Little Big Man, Thomas Berger - 1999

- Under the Stars and Bars, J.T.Edson

Music

- Ramblin' Gamblin' Willie, Bob Dylan

See also

- The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok

- Deadwood, South Dakota

- William Cutolo

- Folk hero

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Martin, George (1975). "Guns of the Gunfighters", Peterson Publishing Company ISBN 0822700956. Retrieved on 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Wild Bill" Hickok Court Documents Nebraska State Historical Society 1861 Subpoena issued to Monroe McCanles to testify against Duck Bill, Dock and Wellman (other names not known)

- ↑ Martin Fido: The Chronicle of Crime 1993 Page 24. ISBN 1844426238 (from an 1861 newspaper article reporting the McCanles shooting)

- ↑ History of Lenexa, Kansas

- ↑ Joseph C. Rosa. 1996. Wild Bill Hickok: the man and his myth, University Press of Kansas.

- ↑ The life of Hon. William F. Cody, known as Buffalo Bill, the famous hunter, scout and guide. An autobiography, F. E. BLISS. HARTFORD, CONN, 1879, p329

- ↑ Buffalo Bill Museum & Grave - Golden, Colorado

- ↑ "Spartacus Educational". Retrieved on 2008-04-13.

- ↑ Joseph G. Rosa, 1996, Wild Bill Hickok: the man and his myth, University Press of Kansas, p. 116.

- ↑ Joseph G. Rosa, 1996, op. cit., pp. 116-123.

- ↑ "The defendant cannot set up justification that he acted in self-defense if he was willing to engage in a fight with deceased. To be entitled to acquittal on the ground of self-defense, he must have been anxious to avoid a conflict, and must have used all reasonable means to avoid it. If the deceased and defendant engaged in a fight or conflict willingly on the part of each, and the defendant killed the deceased, he is guilty of the offense charged, although the deceased may have fired the first shot."

- ↑ "That when danger is threatened and impending a man is not compelled to stand with his arms folded until it is too late to offer successful resistance & if the jury believe from the evidence that Tutt was a fighting character & a dangerous man & that Deft was aware such was his character & that Tutt at the time he was shot by the Deft was advancing on him with a drawn pistol & that Tutt had previously made threats of personal injury to Deft ... & that Deft shot Tutt to prevent the threatened impending injury [then] the jury will acquit"

- ↑ Legal Culture, Wild Bill Hickok and the Gunslinger Myth Steven Lubet UCLA Law Review Volume 48, Number 6 (2001)

- ↑ James Butler Hickok/"Wild Bill" Margaret Odrowaz-Sypniewska B.F.A.

- ↑ http://www.droversmercantile.com/history.cfm

- ↑ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/WWhickok.htm

- ↑ Ironically Kyle had been awarded the MOH![[1]]

- ↑ City Marshal Thomas J. Smith, Abilene Police Department

- ↑ Joseph G. Rosa, 1996, Wild Bill Hickok: the man and his myth, University Press of Kansas, p. 110.

- ↑ John Wesley Hardin Collection Texas State University

- ↑ Shooting stray dogs within city limits was legal and a 50-cent bounty was paid by the city for each one shot.

- ↑ http://www.odmp.org/officer.php?oid=16507

- ↑ Who was Wild Bill Hickok?

- ↑ Page #21 in a loose leaf notebook titled Early days In Abilene Theophilus Little

- ↑ Hickok's death chair

- ↑ After his execution it was determined that McCall never had a brother.

- ↑ "A Trip to the Black Hills" Leander P. Richardson Scribner's (April 1877) New York Times August 13, 1877

- ↑ McCall alleged that John Varnes, a Deadwood gambler, had paid him to murder Wild Bill. When Varnes could not be found, McCall then implicated Tim Brady in the plot. Brady, like Varnes, had disappeared from Deadwood and could not be found.

- ↑ Jack McCall & The Murder of Wild Bill Hickok - Black Hills visitor Magazine.

References

- Matheson, Richard (1996). The Memoirs of Wild Bill Hickok. Jove. ISBN 0-515-11780-3.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1979). They Called Him Wild Bill. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1538-6.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1994). The West of Wild Bill Hickok. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2680-9.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1996). Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0773-0.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (2003). Wild Bill Hickok Gunfighter: An Account of Hickok's Gunfights. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3535-2.

- Turner, Thadd M. (2001). Wild Bill Hickok: Deadwood City - End of Trail. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1-58112-689-1.

- Wilstach, Frank Jenners (1926). Wild Bill Hickok: The Prince of Pistoleers. Doubleday, Page & company. ASIN B00085PJ58.

External links

- Profile by Don Collier

- Wild Bill Hickok collection at Nebraska State Historical Society

- Today at High Noon: The First Showdown - Blog post on Hickok's first showdown.

|

|||||||||||||||||