War of the Triple Alliance

| War of the Triple Alliance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

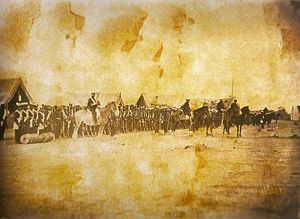

Colonel Faria da Rocha reviewing Brazilian troops in front of the Tayi market, 1868. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 150,000 Paraguayans | 164,173 Brazilians, 30,000 Argentines, 5,583 Uruguayans Total: 199,756 men |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ca. 300,000 soldiers and civilians | 90,000 to 100,000 soldiers and civilians | ||||||

|

|||||

The War of the Triple Alliance, also known as the Paraguayan War, and the Great War in Paraguay itself, was fought from 1864 to 1870, and caused more deaths than any other South American war. It is known as the bloodiest war in Latin American history. It was fought between Paraguay and the allied countries of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay.

Contents |

Overview

The start of the war has been widely attributed to causes as varied as the after-effects of colonialism in Latin America, the struggle for physical power over the strategic Río de la Plata region, Brazilian and Argentine meddling in internal Uruguayan politics, British economic interests in the region, and the expansionist ambitions of Paraguayan president Francisco Solano López.[1] Paraguay has had boundary disputes and tariff issues with Argentina and Brazil for many years.

The outcome of the war was the utter defeat of Paraguay. After the Triple Alliance defeated Paraguay in conventional warfare, the conflict turned into a drawn-out guerrilla-style resistance that would devastate the Paraguayan population, both military and civilian. The guerilla war lasted until Lopez was killed on March 1, 1870. One estimate places total Paraguayan losses — through both war and disease — as high as 1.2 million people, or 90% of its pre-war population.[2][3] A different estimate places Paraguayan deaths at approximately 300,000 people out of its 500,000 to 525,000 prewar inhabitants.[4]

It took decades for Paraguay to recover from the chaos and demographic imbalance in which it had been placed: What had been by name one of the first South American republics, Paraguay only chose its first democratically-elected president in 1993. In Brazil, the war helped bring about the end of slavery, moved the military into a key role in the public sphere, and caused a ruinous increase of public debt, which took decades to pay, seriously reducing the country's growth. It has been argued that the war played a key role in the consolidation of Argentina as a nation-state. [5] After the war, that country became Latin America's wealthiest nation. For Uruguay, it was the last time that Brazil and Argentina would take such an interventionist role in its internal politics.[6]

The setup

Paraguay before the war

Historians have long considered that Paraguay under José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1813–1840) and Carlos Antonio López (1841–1862) developed quite differently from other South American countries. The aim of Rodríguez de Francia and Carlos López was to encourage self-sufficient economic development in Paraguay by imposing isolation from neighboring countries.[7] But historiography is ever-changing: in the 1960s and 1970s, many historians claimed that the War of the Triple Alliance was caused by pseudo-colonial influence of the British who were in need of a new source of cotton due to the United States civil war. [5] But this claim it is unfounded on historical research [8] and has been discredited by several historical works that have appeared since the 1990s.[9]

The regime of the López family was characterized by a harsh centralism without any room for the creation of a true civil society. There was no distinction between the public and the private sphere, and the López family ruled the country as it would a large property estate.[10]

The government controlled all exports. The yerba maté and valuable wood exported maintained the balance of commerce.[11] Paraguay was extremely protectionist, never accepting loans from the outside and, through high tariffs, refusing the entrance of foreign products. Francisco Solano López, son of Carlos Antonio López, replaced his father as president-dictator in 1862, and generally continued the political policies of his predecessors.

In the area of the military, however, Solano López modernized and expanded in ways that eventually would lead to war.[12] More than 200 foreign technicians, hired by the government, installed telegraph lines and railroads to aid the steel, textiles, paper, ink, naval construction and gunpowder industries. The Ybycuí foundry, installed in 1850, manufactured cannons, mortars and bullets of all calibers. Warships were built in the Asunción shipyards.

This growth required contact with the international market, but Paraguay was landlocked. Its ports were river ports and ships had to travel down the Río Paraguay and the Río Paraná to reach the estuary of the Río de la Plata and the ocean. Solano López conceived a project to obtain a port in the Atlantic Ocean: he perhaps intended to create a "Greater Paraguay" by capturing a slice of Brazilian territory that would link Paraguay to the coastline.[13]

To maintain his expansionist intentions, López began to prepare Paraguay's military. He encouraged the industry of war, mobilized a large quantity of men for the army (mandatory military service already existed in Paraguay), submitted them to intensive military training, and built fortifications at the mouth of the Río Paraguay.

Diplomatically, Solano López wanted to ally himself with Uruguay's ruling Blanco Party. The Colorados were tied to Brazil and Argentina.[14]

In 1864 Lopez thought the balance of power was threatened when Brazil got involved in Uruguay's politics and struggle for leadership. This caused Lopez to declare war on Brazil. Argentina stayed neutral and only declared war on Paraguay when this country invaded Corrientes province after Mitre rejected the request Solano made to use Argentinean territory to move his troops to fight in Uruguay against Brazil.

Politics of the Río de la Plata

Since Brazil and Argentina had become independent, the fight between the governments of Buenos Aires and of Rio de Janeiro for hegemony in the Río de la Plata profoundly marked the diplomatic and political relations between the countries of the region.[15] Brazil almost entered into war with Argentina twice.

The government of Buenos Aires intended to reconstruct the territory of the old Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, enclosing Paraguay and Uruguay. It carried out diverse attempts to do so during the first half of the 19th century, without success — many times due to Brazilian intervention. Fearing excessive Argentine control, Brazil favored a balance of power in the region, helping Paraguay and Uruguay retain their sovereignty.

Brazil, under the rule of the Portuguese, was the first country to recognize the independence of Paraguay in 1811. While Argentina was ruled by Juan Manuel Rosas (1829–1852), a common enemy of both Brazil and Paraguay, Brazil contributed to the improvement of the fortifications and development of the Paraguayan army, sending officials and technical help to Asunción. As no roads linked the province of Mato Grosso to Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian ships needed to travel through Paraguayan territory, going up the Río Paraguay to arrive at Cuiabá. Many times, however, Brazil had difficulty obtaining permission to sail from the government in Asunción.

Brazil carried out three political and military interventions in Uruguay — in 1851, against Manuel Oribe to fight Argentine influence in the country; in 1855, at the request of the Uruguayan government and Venancio Flores, leader of the Colorados, who were traditionally supported by the Brazilian empire; and in 1864, against Atanásio Aguirre. This last intervention would be the fuse of the War of the Triple Alliance. These interventions were aligned to the British desire for the fragmentation of the Río de la Plata region to stop any attempt to monopolize the region's minerals as well as the control of both shores of the Río de la Plata, therefore, controlling the access of all ships going upriver.

Intervention against Aguirre

In April 1864, Brazil sent a diplomatic mission to Uruguay led by José Antônio Saraiva to demand payment for the damages caused to gaucho farmers in border conflicts with Uruguayan farmers. The Uruguayan president Atanásio Aguirre, of the National Party, refused the Brazilian demands.

Solano López offered himself as mediator, but was turned down by Brazil. López subsequently broke diplomatic relations with Brazil — in August 1864 — and declared that the occupation of Uruguay by Brazilian troops would be an attack on the equilibrium of the River Plate region.

On October 12, Brazilian troops invaded Uruguay. The followers of the Colorado Venancio Flores, who had the support of Argentina, united with the Brazilian troops and deposed Aguirre.[16]

The War

The war begins

When attacked by Brazil, the Uruguayan Blancos asked for help from Solano López, but Paraguay did not directly come to their ally's aid. Instead, on November 12, 1864, the Paraguayan ship Tacuari captured the Brazilian ship Marquês de Olinda which had sailed up the Río Paraguay to the province of Mato Grosso.[17] Paraguay declared war on Brazil on December 13 and on Argentina three months later, on March 18, 1865. Uruguay, already governed by Venancio Flores, aligned itself with Brazil and Argentina.

At the beginning of the war, the military force of the Triple Alliance was inferior to that of Paraguay, which included, according to revisionist historians, more than 60,000 well-trained men—38,000 of whom were immediately under arms—and a naval squadron of twenty-three steamboats (vapores) and five river-navigating ships, based around the gunboat the Tacuari.[18] Its artillery included about 400 cannons. However, recent studies has shown a different picture. Although the Paraguayan army had somewhere between 70,000 and 100,000 men at the beginning of the conflict, they were badly equipped. Most of the infantry armament consisted of rifles and carbines with flintlock and smooth barrels, with slow recharge, short reach and little precision. The same applied to the artillery. The officers had no training or experience at all and there was no command system, as all decisions were made by López. There was scarcity of food, ammunition and armament and the service of logistics and hospital care were pretty much deficient if not nonexistent.[19]

The armies of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay were a fraction of the total size of the Paraguayan army. Argentina had approximately 8,500 regular troops and a squadron of four vapores and one goleta. Uruguay entered the war with fewer than 2,000 men and no navy. Many of Brazil's 16,000 troops were initially located in its southern garrisons.[20] The Brazilian advantage, though, was in its navy: 42 ships with 239 cannon and about 4,000 well-trained crew. A great part of the squadron already met in the River Plate basin, where it had acted, under the Marquis of Tamandaré, in the intervention against Aguirre.

Brazil, however, was unprepared to fight a war. Its army was unorganized. The troops used in the interventions in Uruguay were composed merely of the armed contingents of gaucho politicians and some of the staff of the National Guard. The Brazilian infantry who fought in the War of the Triple Alliance were not professional soldiers but volunteers, the so called Voluntários da Pátria. The army was heavily recruited from the landless, largely black, underclass. [21] The cavalry was formed from the National Guard of Rio Grande Do Sul. From the end of 1864 to 1870 something like 146,173 Brazilians fought in the war while 18,000 members of the National Guard stayed behind in Brazilian territory to defend it, bringing to a total of 164,173 men. The 147,173 soldiers were divided in: 10,025 soldiers of the army stationed in Uruguayan territory in 1864, 2,047 that were in the province of Mato Grosso, 55,985 Fatherland Volunteers, 60,009 National Guards, 8,570 ex-slaves (that had been freed to be sent to war) and 9,177 military of the navy.[22]

Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay would sign the Treaty of the Triple Alliance in Buenos Aires on May 1, 1865, allying the three River Plate countries against Paraguay. They named Bartolomé Mitre, president of Argentina, as supreme commander of the allied troops.[23]

Paraguayan offensive

During the first phase of the war Paraguay took the initiative. The armies of López dictated the location of initial battles — invading Mato Grosso in the north in December 1864, Rio Grande do Sul in the south in the first months of 1865 and the Argentine province of Corrientes.

Two bodies of Paraguayan troops invaded Mato Grosso simultaneously. Due to the numerical superiority of the invaders the province was captured quickly.

Five thousand men, transported in ten ships and commanded by the colonel Vicente Barrios, went up the Río Paraguay and attacked the fort of Nova Coimbra. The garrison of 155 men resisted for three days under the command of the lieutenant-colonel Hermenegildo de Albuquerque Porto Carrero, later baron of Fort Coimbra. When the munitions were exhausted the defenders abandoned the fort and withdrew up the river on board the gunship Anhambaí in direction of Corumbá. After they occupied the empty fort the Paraguayans advanced north taking the cities of Albuquerque and Corumbá in January 1865.

The second Paraguayan column, which was led by Colonel Francisco Isidoro Resquín and included four thousand men, penetrated a region south of Mato Grosso, and sent a detachment to attack the military frontier of Dourados. The detachment, led by Major Martín Urbieta, encountered tough resistance on December 29, 1864 from Lieutenant Antonio João Ribeiro and his 16 men, who died without yielding. The Paraguayans continued to Nioaque and Miranda, defeating the troops of the colonel José Dias da Silva. Coxim was taken in April 1865.

The Paraguayan forces, despite their victories, did not continue to Cuiabá, the capital of the province. Augusto Leverger had fortified the camp of Melgaço to protect Cuiabá. The main objective was to distract the attention of the Brazilian government to the north as the war would lead to the south, closer to the River Plate estuary. The invasion of Mato Grosso was a diversionary maneuver.

The invasion of Corrientes and of Rio Grande do Sul was the second phase of the Paraguayan offensive. To raise the support of the Uruguayan Blancos, the Paraguayan forces had to travel through Argentine territory. In March of 1865, López asked the Argentine government's permission for an army of 25,000 men (led by General Wenceslao Robles) to travel through the province of Corrientes. The president - Bartolomé Mitre, an ally of Brazil in the intervention in Uruguay - refused.

On March 18, 1865, Paraguay declared war on Argentina. A Paraguayan squadron, coming down the Río Paraná, imprisoned Argentine ships in the port of Corrientes. Immediately, General Robles's troops took the city.

By invading Corrientes, López tried to obtain the support of the powerful Argentine caudillo Justo José de Urquiza, governor of the provinces of Corrientes and Entre Ríos, and the chief federalist hostile to Mitre and to the government of Buenos Aires.[24] But Urquiza assumed an ambiguous attitude towards the Paraguayan troops —which would advance around 200 kilometers south before ultimately ending the offensive in failure.

Along with Robles's troops, a force of 10,000 men under the orders of the lieutenant-colonel Antonio de la Cruz Estigarriba crossed the Argentine border south of Encarnación, in May 1865, driving for Rio Grande do Sul. They traveled down Río Uruguay and took the town of São Borja on June 12. Uruguaiana, to the south, was taken on August 5 without any significant resistance. The Brazilian reaction was yet to come.

Brazil reacts

Brazil sent an expedition to fight the invaders in Mato Grosso. A column of 2,780 men led by Colonel Manuel Pedro Drago left Uberaba in Minas Gerais in April 1865, and arrived at Coxim in December after a difficult march of more than two thousand kilometers through four provinces. But Paraguay had abandoned Coxim by December. Drago arrived at Miranda in September 1866 - and Paraguay had left once again. In January 1867, Colonel Carlos de Morais Camisão assumed command of the column, now with only 1,680 men, and decided to invade Paraguayan territory, where he penetrated as far as Laguna. The expedition was forced to retreat by the Paraguayan cavalry.

Despite the efforts of Colonel Camisão's troops and the resistance in the region, which succeeded in liberating Corumbá in June 1867, Mato Grosso remained under the control of the Paraguayans. They finally withdrew in April 1868, moving their troops to the main theatre of operations, in the south of Paraguay.

Communications in the River Plate basin was solely by river; few roads existed. Whoever controlled the rivers would win the war, so the Paraguayan fortifications had been built on the edges of the lower end of Río Paraguay.

The naval battle of Riachuelo occurred on June 11, 1865. The Brazilian fleet commanded by Francisco Manoel Barroso da Silva won, destroying the powerful Paraguayan navy and preventing the Paraguayans from permanently occupying Argentine territory. The battle practically decided the outcome of the war in favour of the Triple Alliance, which controlled, from that point on, the rivers of the River Plate basin up to the entrance to Paraguay.[25]

While López ordered the retreat of the forces that occupied Corrientes, the Paraguayan troops that invaded São Borja advanced, taking Itaqui and Uruguaiana. A separate division (3,200 men) that continued towards Uruguay, under the command of the major Pedro Duarte, was defeated by Flores in the bloody battle of Jataí on the banks of the Río Uruguay.

The allied troops united under the command of Mitre in the camp of Concordia, in the Argentine province of Entre Ríos, with the field-marshal Manuel Luís Osório at the front of the Brazilian troops. Part of the troops, commanded by the lieutenant-general Manuel Marques de Sousa, baron of Porto Alegre, left to reinforce Uruguaiana. The Paraguayans yielded on September 18, 1865.

In the subsequent months the Paraguayans were driven out of the cities of Corrientes and San Cosme, the only Argentine territory still in Paraguayan possession. By the end of 1865, the Triple Alliance was on the offensive. Their armies numbered more than 50,000 men and were prepared to invade Paraguay.

Caxias in command

Assigned on October 10, 1866 to command the Brazilian forces, Marshal Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Marquis and, later, Duke of Caxias, arrived in Paraguay in November, finding the Brazilian army practically paralyzed. The contingent of Argentines and Uruguayans, devastated by disease, were cut off from the rest of the allied army. Mitre and Flores returned to their respective countries due to questions of internal politics. Tamandaré was replaced in command by the Admiral Joaquim José Inácio, future Viscount of Inhaúma. Osório organized a 5,000-strong third Corps of the Brazilian army in Rio Grande do Sul. In Mitre's absence, Caxias assumed the general command and restructured the army.

Between November 1866 and July 1867, Caxias organized a health corps (to give aid to the endless number of injured soldiers and to fight the epidemic of cholera) and a system of supplying of the troops. In that period military operations were limited to skirmishes with the Paraguayans and to bombarding Curupaity. López took advantage of the disorganization of the enemy to reinforce his stronghold in Humaitá.

The march to flank the left wing of the Paraguayan fortifications constituted the basis of Caxias's tactics. Caxias wanted to bypass the Paraguayan strongholds, cut the connections between Asunción and Humaitá, and finally circle the Paraguayans. To this end, Caxias marched to Tuiu-Cuê. But Mitre, who had returned to the command in August 1867, insisted on attacking by the right wing, a strategy that had previously been disastrous in Curupaity. By his order, the Brazilian squadron forced its way past Curupaity but was forced to stop at Humaitá. New splits in the high command arose: Mitre wanted to continue, but the Brazilians instead captured São Solano, Pike and Tayi, isolating Humaitá from Asunción. In reaction, López attacked the rearguard of the allies in Tuiuti, but suffered new defeats.

With the removal of Mitre in January 1868, Caxias reassumed the supreme command and decided to bypass Curupaity and Humaitá, carried out with success by the squadron commanded by Captain Delfim Carlos de Carvalho, later Baron of Passagem. Humaitá fell on 25 July after a long siege.

En route to Asunción, Caxias's army went 200 kilometers to Palmas, stopping at the Piquissiri river. There López had concentrated 18,000 Paraguayans in a fortified line that exploited the terrain and supported the forts of Angostura and Itá-Ibaté. Resigned to frontal combat, Caxias ordered the so-called Piquissiri maneuver. While a squadron attacked Angostura, Caxias made the army cross on the right side of the river. He ordered the construction of a road in the swamps of the Chaco, upon which the troops advanced to the northeast. At Villeta, the army crossed the river again, between Asunción and Piquissiri, behind the fortified Paraguayan line. Instead of it advancing to the capital, already evacuated and bombarded, Caxias went south and attacked the Paraguayans from behind.

Caxias had obtained a series of victories in December 1868, when he went back south to take Piquissiri from the rear, capturing Itororó, Avaí, Lomas Valentinas and Angostura. On December 24 the three new commanders of the Triple Alliance (Caxias, the Argentine Juan Andrés Gelly y Obes, and the Uruguayan Enrique Castro) sent a note to Solano López asking for surrender. But López turned it down and fled for Cerro Leon.

Asunción was occupied on January 1, 1869 by commands of Colonel Hermes Ernesto da Fonseca, father of the future Marshal Hermes da Fonseca. On the fifth day, Caxias entered in the city with the rest of the army and 13 days later left his command.

The end of the war

Command of Count d'Eu

The son-in-law of the emperor Dom Pedro II, Luís Filipe Gastão de Orléans, Count d'Eu, was nominated to direct the final phase of the military operations in Paraguay. He sought not just a total rout of Paraguay, but also the strengthening of the Brazilian Empire. In August 1869, the Triple Alliance installed a provisional government in Asunción headed by Paraguayan Cirilo Antonio Rivarola.

Solano López organized the resistance in the mountain range northeast of Asunción. At the head of 21,000 men, Count d'Eu led the campaign against the Paraguayan resistance, the Campaign of the Mountain Range, which lasted over a year. The most important battles were the battles of Piribebuy and of Acosta Ñu, in which more than 5,000 Paraguayans died.

Two detachments were sent in pursuit of Solano López, who was accompanied by 200 men in the forests in the north. On March 1, 1870, the troops of General José Antônio Correia da Câmara surprised the last Paraguayan camp in Cerro Corá, where Solano López was fatally injured by a spear as he tried to swim away down the Aquidabanigui stream. His last words were: "Muero por mi patria" (I die for my homeland). This marks the end of the war of the Triple Alliance.

Mortality

The Paraguayan people had been fanatically committed to López and the war effort, and as a result they fought to the point of dissolution. Paraguay suffered massive casualties, losing perhaps the majority of its population. The war left it utterly prostrate.

The specific numbers of casualties are hotly disputed, but it has been estimated that 300,000 Paraguayans, mostly civilians, died; up to 90% of the male population may have been killed. According to one numerical estimation, the prewar population of approximately 525,000 Paraguayans was reduced to about 221,000 in 1871, of which only about 28,000 were men. Definitively accurate casualty numbers will probably never be determined.

Of the around 123,000 Brazilians that fought in the War of the Triple Alliance, the best estimates say that around 50,000 died. Uruguayan forces counted barely 5,600 men (some of whom were foreigners), of whom about 3,100 died. Argentina lost around 18,000 of its 30,000 combatants.

The high rates of mortality, however, were not the result of the armed conflict in itself. Bad food and very bad hygiene caused most of the deaths. Among the Brazilians, two-thirds of the killed died in hospitals and during the march, before facing the enemy. In the beginning of the conflict, most of the Brazilian soldiers came from the north and northeast regions of the country; the changes from a hot to cold climate and the amount of food available to them were abrupt. Drinking the river water was sometimes fatal to entire battalions of Brazilians. Cholera was, perhaps, the main cause of death during the war.

Consequences of the war

Following Paraguay's final defeat in 1870, Argentina sought to enforce one of the secret clauses of the Triple Alliance Treaty, according to which Argentina would receive a large part of the Gran Chaco, a Paraguayan region rich in quebracho (a product used in the tanning of leather). The Argentinian negotiators proposed to Brazil that Paraguay should be divided in two, with each of the victors incorporating a half into its territory. The Brazilian government, however, was not interested in the end of the Paraguayan state, since it served as a cushion between the Brazilian Empire and Argentina.

A standstill began, and the Brazilian army, which was in complete control of the Paraguayan territory, remained in the country for six years after the final defeat of Paraguay in 1870, only leaving in 1876 in order to ensure the continued existence of Paraguay. During this time, the possibility of an armed conflict with Argentina for control over Paraguay became increasingly real, as Argentina wanted to seize the Chaco region, but was barred by the Brazilian Army.

No single overall peace treaty was signed. The post-war border between Paraguay and Argentina was resolved through long negotiations, finalized in a treaty that defined the frontier between the two countries signed on February 3, 1876 and which granted Argentina roughly a third of the area it had intended to incorporate originally. The only region about which no consensus was reached — the area between the Río Verde and the main branch of Río Pilcomayo — was arbitrated by U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, who declared it Paraguayan. (The Paraguayan department Presidente Hayes was named after Hayes due to his arbitration decision.) Brazil signed a separate peace treaty with Paraguay on January 9, 1872, obtaining freedom of navigation on the Río Paraguay. Brazil received the borders it had claimed before the war. The treaty also stipulated a war debt to the imperial government of Brazil that was eventually pardoned in 1943 by Getúlio Vargas in reply to a similar Argentine initiative.

In December 1975, when the presidents Ernesto Geisel and Alfredo Stroessner signed in Asunción a Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, the Brazilian government returned its spoils of war to Paraguay, except the Paraguayan national archives which were removed during the ransacking of Asuncion and taken to the National library in Rio de Janeiro.

The war still remains a controversial topic - especially in Paraguay, where it is considered either a fearless struggle for the rights of a smaller nation against the aggressions of more powerful neighbours, or a foolish attempt to fight an unwinnable war that almost destroyed a whole nation. In Argentina, as the war wore on, many Argentines saw the conflict as Mitre's war of conquest, and not as a response to aggression. They remembered that Solano López, believing he would have Mitre's support, seized the opportunity to attack Brazil created by Mitre, when he used the Argentinian Navy to deny access to the River Plate to Brazilian ships in early 1865, thus starting the war.

The Paraguayan villages destroyed by the war were abandoned and the peasant survivors migrated to the outskirts of Asunción, dedicating themselves to subsistence agriculture in the central region of the country. Other lands were sold to foreigners, mainly Argentines, and turned into estates. Paraguayan industry fell apart. The Paraguayan market opened itself to British products and the country was forced for the first time to get outside loans - totalling a million British pounds. In fact, Britain can be seen as the power that most benefited from the war: whilst the war ended the Paraguayan threat to their interests, Brazil and Argentina fell into massive debt, establishing a pattern that continues to this day. (Brazil repaid all British loans by the Getúlio Vargas era.)

Argentina annexed part of Paraguayan territory and became the strongest of the River Plate countries. During the campaign, the provinces of Entre Rios and Corrientes had supplied Brazilian troops with cattle, foodstuffs and other products.

Brazil paid a high price for victory. The war was financed by the Bank of London, and by Baring Brothers and N M Rothschild & Sons. During the five years of war, Brazilian expenditure reached twice its receipts, causing a financial crisis.

In total, Argentina and Brazil annexed about 140,000 km² (55,000 square miles) of Paraguayan territory: Argentina took much of the Misiones region and part of the Chaco between the Bermejo and Pilcomayo rivers, an area which today constitutes the province of Formosa; Brazil enlarged its Mato Grosso province by claiming territories that had been disputed with Paraguay before the war. Both demanded a large indemnity (which was never paid) and occupied Paraguay until 1876. Meanwhile, the Colorados had gained political control of Uruguay, which they retained until 1958.

Slavery was undermined in Brazil as slaves were freed to serve in the war.[26] The Brazilian army became a new and expressive force in national life. It transformed itself into a strong institution that, with the war, gained tradition and internal cohesion and would take a significant role in the later development of the history of the country.

The war took its biggest toll on the Brazilian emperor. The economic depression and the fortification of the army would later play a big role in the deposition of the emperor Dom Pedro II and the republican proclamation in 1889. General Deodoro da Fonseca would become the first Brazilian president.

Notes

- ↑ Miguel Angel Centeno, Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1957. Page 55.

- ↑ Byron Farwell, The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View, New York: WW Norton, 2001. Page 824.

- ↑ Another estimate is that from the prewar population of 1,337,437, the population fell to 221,709 (28,746 men, 106,254 women, 86,079 children) by the end of the war (War and the Breed, David Starr Jordan, p. 164. Boston, 1915; Applied Genetics, Paul Popenoe, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1918)

- ↑ Jurg Meister, Francisco Solano López Nationalheld oder Kriegsverbrecher?, Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 1987. 345, 355, 454-5.

- ↑ Historia de las relaciones exteriores de la República Argentina (notes from CEMA University, in spanish, and references therein) [1]

- ↑ Scheina, 331.

- ↑ PJ O'Rourke, Give War a Chance. New York: Vintage Books, 1992. Page 47.

- ↑ SALLES, Ricardo. Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens. Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional, 2003, pg.14

- ↑ SALLES, Ricardo. Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens. Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional, 2003, pg.14

- ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies, "Carlos Antonio López." December 1988. [2] URL accessed December 30 2005.

- ↑ Page 630 from The Encyclopedia of World History Sixth Edition, Peter N. Stearns (general editor), © 2001 The Houghton Mifflin Company, at Bartleby.com.

- ↑ Robert Cowley, The Reader's Encyclopedia to Military History. New York, New York: Houston Mifflin, 1996. Page 479.

- ↑ Brandon Valeriano, "A Classification of Interstate War: Typologies and Rivalry." Article based on talk given March 17-20, 2004 to the International Studies Association in Montreal. File available at [3], accessed December 30 2005.

- ↑ Scheina, 313-4.

- ↑ Whigwham, 118.

- ↑ Scheina, 314.

- ↑ Scheina, 313.

- ↑ Scheina, 315-7.

- ↑ SALLES, Ricardo. Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens. Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional, 2003, pg.18

- ↑ Scheina, 318.

- ↑ Wilson.

- ↑ SALLES, Ricardo. Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens. Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional, 2003, pg.38

- ↑ Scheina, 319.

- ↑ Scheina, 319.

- ↑ Scheina, 320.

- ↑ Hendrik Kraay, Journal of Social History, "'The shelter of the uniform': the Brazilian army and runaway slaves, 1800-1888" Spring 1996.[4]

Diego Abente, The War of the Triple Alliance, Latin American Research Review, 1987, Vol. 22, No. 2, 47-69 Osgood Hardy, South American Alliances: Some Political and Geographical Considerations, Geographical Review, Oct. 1919, Vol. 8, No. 4/5, 259-265 Jose Alfredo Fornos Penalba, Draft Dodgers, War Resisters, Turbulent Gauchos: The War of the Triple Alliance againist Paraguay,The Americas, April 1982, Vol. 38 No. 4, 463-479

References

- Robert Scheina, Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791-1899, Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's, 2003.

- Chris Leuchars. To the Bitter End: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Thomas Whigham. The Paraguayan War, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

- Jose Alfredo Fornos Penalba, Draft Dodgers, War Resisters and Turbulent Gauchos: The War of the Triple Alliance against Paraguay, The Americas, Vol.38, No.4. (Apr., 1982), pp.463-479.

- John Hoyt Williams, The Battle of Tuyuti, Military History; April 2000, Vol.17 Issue 1, p58.

- Peter Wilson, Latin America's Total War, History Today, 00182753, May 2004, Vol. 54, Issue 5.

- This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

Encyclopedia Britannica. http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9058388

See also

- List of battles of the War of the Triple Alliance

- Triple Alliance War casualties

- List of conflicts in the Americas

External links

- Paraguay The War of the Triple Alliance

- Page at countrystudies.us

- The War of Paraguay (Portuguese)

- The War of Paraguay - history (Portuguese)

- http://www.geocities.com/Pentagon/Camp/2523 (English)

- Wargame of Naval Battle of Riachuelo - wargame (Portuguese)

- 'Paraguay de Antes' (old photos & pics) (Spanish)

- Cerro Corá in Google Maps

- Military Orders and Medals from Brazil (Portuguese)

Novels about the war

In Portuguese

- Carlos de Oliveira Gomes, A Solidão Segundo Solano Lopez, Círculo do Livro, 1982.

- Joseph Eskenazi Pernidji and Mauricio Eskenazi e Pernidji. Homens e Mulheres na Guerra do Paraguai. Imago, 2003.

Movies

- Cerro Cora, by Guillermo Vera, Paraguay (1978).

- Netto perde sua alma, by Beto Souza e Tabajara Ruas, Brazil (2001).

- Cándido López - Los campos de batalla. by José Luis García, Argentina (2005).