War of the Pacific

| War of the Pacific | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

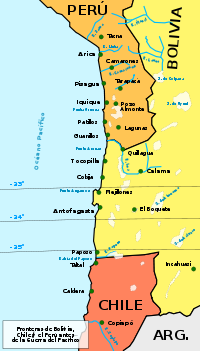

Map showing changes of territory due to the war[1] ceded by Bolivia to Chile 1874 ceded by Bolivia to Chile in 1883 ceded by Peru to Chile in 1883 ceded by Peru to Chile in 1929 occupied by Chile until 1929 ceded by Chile to Argentina in 1899 national borders in 1874 national borders since 1929 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Peru-Bolivian Army 7,000 soldiers in 1878 Peruvian army: 40,000 in 1881 Peruvian Navy 2 ironclad, 1 corvette, 1 gunboat |

Army of Chile 4,000 soldiers in 1878 Army of Chile: 45,000 in 1881 Chilean Navy 2 battleship, 4 corvettes, 2 gunboats |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 35,000 Peruvians killed or wounded, 5000 Bolivians killed or wounded | 15,000 killed or wounded | ||||||||

|

|||||

The War of the Pacific, occurring from 1879-1883, is sometimes referred to as the Saltpeter War in reference to its original cause, a conflict that involved Chile and the joint forces of Bolivia and Peru. The conflict stemmed from the control of territory that contained substantial mineral-rich deposits. It led to the Chilean annexation of the Peruvian provinces of Tarapacá and Arica and the Bolivian province of Litoral, leaving Bolivia as a landlocked country.

Contents |

Origins of the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific grew out of the initial dispute between Chile and Bolivia for control over a part of the Atacama desert that lies between the 23rd and 26th parallels on the Pacific coast. The territory contained valuable mineral resources that were being exploited by Chilean companies and British interests. The Bolivian government decided to increase taxes to take advantage of the increasing income of the region, and that led to a commercial dispute.

Since the border treaty of 1874 did not allow for such a tax hike, the companies thought that the increased payments were unfair and demanded that the Chilean government intervene. This request led to a diplomatic crisis and ultimately revealed Peru's secret defense alliance with Bolivia.

Control of natural resources

The dry climate of the area had permitted the accumulation and preservation of vast amounts of high-quality nitrate deposits — guano and saltpeter over many thousands of years. The discovery during the 1840s of the use of guano as a fertilizer and saltpeter as a key ingredient in explosives made the area strategically valuable; Bolivia, Chile, and Peru had suddenly found themselves sitting on the largest reserves of a resource that the world needed for economic and military purposes.

Not long after this discovery, world powers were both directly and indirectly vying for control of the area's resources. The United States of America passed the Guano Islands Act in 1856, which enabled its citizens to take possession of unoccupied islands containing guano. Spain had seized some Peruvian territory, but it was repulsed by Peru and Chile - fighting as allies during the Chincha Islands War. Heavy British capital investment drove development through the area, although Peru nationalized the guano exploitation during the 1870s.

(Common cause Chincha Islands war: Between 1864-1866, Spain became envious of the guano-rich Chincha Islands. Spain failed to seize guano, and consequently war broke out among Spain, Peru, and Chile.)

Border dispute

Bolivian and Chilean historians disagree on whether the territory of Charcas, originally part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, later of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata belonged to Bolivia or not. Supporting their claims with different documents, Bolivians claim that it did while Chileans disagreed. When Simón Bolívar established Bolivia as a nation, he claimed that it needed access to the oceans, although most of the exploitation of the coastal region was to be conducted by Chilean companies and British interests.

No permanant borders have been established. In 1866, the two countries had negotiated a treaty[2] (commonly referred to as the Treaty of Mutual Benefits) that established the 24th parallel as their boundary, and entitled Chile the right to share in the tax revenue on mineral exports from the territory between the 23rd and 25th parallels. Within this zone, Chile and Bolivia were provided equal rights. In 1874, second treaty superseded that one, granting Bolivia the authority to to collect full tax revenue between the 23rd and 24th parallels, fixed the tax rates on Chilean companies for 25 years, and called for Bolivia to open up.[2] Bolivia quickly became dissatisfied with the arrangement, since Chilean interests, backed by British capital quickly expanded and controlled the mining industry, and Bolivia feared Chilean encroachment into its coastal region. [3]

Crisis and war

In 1878, the Bolivian government of President Hilarión Daza decreed a backdated 1874 tax increase on Chilean companies, over protests by the Chilean government of President Aníbal Pinto, that the border treaty did not allow for such an increase. When the Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company refused to pay, the Bolivian government threatened to confiscate its property. Chile responded by sending a warship to the area in December of 1878. Bolivia announced the seizure and auction of the company on February 14, 1879. Chile, in turn, threatened that such action would render the border treaty null and void. On the day of the auction, 2000 Chilean soldiers arrived, disembarked and claimed the port city of Antofagasta without a fight.

Now facing a territorial issue, Bolivia declared war a week later, and invoked its secret defensive alliance with Peru: the Defensive Treaty of 1873.[4] The Peruvian government was determined to honor its alliance with Bolivia to contain what they perceived as Chile's expansionist ambitions in the region, but was concerned that Allied forces were not in shape to face the Chilean Army. A peaceful resolution was preferred. Peru attempted to mediate by sending a senior diplomat to negotiate with the Chilean government. Chile requested neutrality but Peru declined, citing the now public treaty with Bolivia. Yet Peru had national issues with Chile, caused from the historical rivalry for control of the Pacific coast.[5] Chile responded by breaking diplomatic ties, and it formally declaring war on both countries on April 5, 1879.

Argentina was invited to join the Alliance since it had a territorial dispute with Chile regarding the region of Patagonia, and was also wary of Chile's position and influence. Its entry in the war seemed possible, and that would have provided an advantage to the anti-Chilean allies. Argentina, however, decided to pursue a peaceful settlement to its own separate dispute and this resulted in Chile's renouncing its claim over a million square miles of Patagonian territory also claimed by Argentina. The Empire of Brazil was, however, a traditional ally of Chile, and it was understood that if Argentina declared war on Chile, that would strain the Argentina-Brazil relations. However Bolivian agents were allowed to buy mules in Argentina for the army.[6]

The War

Bolivia, after several short-lived governments, stood unprepared to face the Chilean army by itself. From the beginning of the war it became clear that, in a difficult desert terrain, control of the sea would prove to be the deciding factor. Bolivia had no navy and Peru faced an economic collapse that left its navy and army without proper training or budget. Most of its warships were old and unable to face battle, leaving only the ironclads Huáscar and Independencia ready. In contrast, Chile – although in the middle of its own economic crisis – was better prepared, counting on its modern navy supplemented by a well-trained and equipped army. When war broke out Argentina sent a naval squadron to Río Negro menacing the Chilean dominion of the Straits of Magellan.[1] , However, it has been argued that the Chilean naval superiority was the main factor preventing Argentina from taking part of the war. [7]

The Battle of Topáter, on 23 March 1879 was the first of the war. On their way to occupy Calama, 554 Chilean troops and cavalry were opposed by 135 Bolivian soldiers and civilian residents led by Dr. Ladislao Cabrera, dug in at two destroyed bridges; calls to surrender were rejected before and during the battle. Outnumbered and low on ammunition, most of the Bolivian force withdrew, except for a small group of civilians led by Colonel Eduardo Abaroa, who fought to the end.

Further land battles would not take place until the war at sea was resolved. Chile declared war on Peru and Bolivia on April 5, 1879.[8]

Under the direction of Rear Admiral Juan Williams, the Chilean navy and its ironclad frigates — Almirante Cochrane and Blanco Encalada — started to operate on the Bolivian and Peruvian coast. The port of Iquique was blockaded, while Huanillos, Mollendo, Pica and Pisagua were bombarded and port facilities burned. Rear Admiral Williams hoped that, by disrupting commerce, especially the saltpeter exports and weapons imports, the Allies' war effort would be weakened and the Peruvian navy thus forced into a decisive showdown.

The smaller, but effective, Peruvian navy did not oblige. Under the command of Admiral Miguel Grau aboard Huáscar, Peru staged a series of blockade runs and harassment raids deep into Chilean waters. The plan was to disrupt Chilean operations, draw the enemy fleet back to the south while avoiding at all costs a fight against superior forces; as a consequence the Chilean invasion would be delayed, the Allies would be free to supply and reinforce their troops along the coast, and weapons would still flow into Peru from the north.

The Naval Battle of Chipana, the first of the war at sea, took place off Huanillos on 12 April 1879, as Peruvian corvettes Unión and Pilcomayo found Chilean corvette Magallanes on its way to Iquique. After a two-hour running artillery duel, Unión suffered engine problems; the pursuit was called off and Magallanes escaped with minor damage.

In the Naval Battle of Iquique of 21 May 1879, Peruvian ironclad ships Huáscar and Independencia lifted the blockade of Iquique by Esmeralda and Covadonga, two of Chile's oldest wooden vessels. Huáscar sank Esmeralda, while Covadonga forced the larger Independencia to run aground at Punta Gruesa (some historians consider this a different engagement and call it the Battle of Punta Gruesa).

The Chilean navy lost a wooden corvette and elevated Captain Arturo Prat of Esmeralda as a martyr to their cause: he died leading a handful of sailors boarding the ironclad after it had rammed his ship. The Peruvian navy lost a powerful ironclad frigate and saw Admiral Miguel Grau's renown grow among friend and foe as a result of his actions: he rescued the survivors of Esmeralda after the battle and wrote condolences to the widow of Captain Prat. Significantly, Huáscar remained the only Peruvian vessel capable of holding off the invasion.

For six months, Huáscar roamed the seas and effectively cut off the Chilean supply lines. In an impressive display of naval mastery, Captain Grau was able to hold off the entire Chilean navy, recover captured Peruvian vessels and severely damage many ports used by the Chileans. These actions are known as the "Correrías del Huáscar" (Huáscar's Exploits) and as a result Grau was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral. A brief listing of these actions include:

- Damaged ports of Cobija, Tocopilla, Platillos and Mejillones, Huanillos, Punta de Lobo, Chanaral, Huasco, Caldera, Coquimbo & Tatal

- Sank 16 Chilean vessels

- Damaged Chilean vessels Blanco Encalada, Abtao, Magallanes, and Matías Cousiño

- Captured Chilean vessels Emilia, Adelaida Rojas, E. Saucy Jack, Adriana Lucía, Rimac, and Coquimbo

- Recovered Peruvian vessels Clorinda and Caquetá

- Destroyed artillery batteries of Antofagasta

- Destroyed Antofagasta-Valparaiso communications cable

It took the Chilean navy a full day of sailing with six ships in order to corner Húascar, and then, nearly two hours of bloody combat with their vessels Blanco Encalada, Covadonga and Cochrane to cause her to founder with 76 artillery hits in the Naval Battle of Angamos on 8 October 1879; the dead included Admiral Grau.

With the capture of Huáscar, the naval campaign was over, and local skirmishes notwithstanding, Chile would control the sea for the duration of the war.

Land Campaign and Invasion

Having gained control of the sea, Chile sent its army to invade Peru. Bolivia, unable to recover the Litoral province, joined the Peruvian defence of Tarapacá and Tacna. However many Bolivians would abandon their allies in the heat of the battle, demoralizing all concerned.

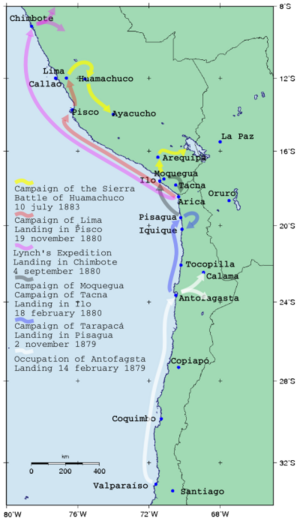

On 2 November 1879, naval bombardment and amphibious assaults were carried out at the small port of Pisagua and the Junín Cove –some 500 km North of Antofagasta. At Pisagua, several landing waves totalling 2,100 troops attacked beach defenses held by 1,160 Allies and took the town; the landing at Junín was smaller and almost unsuccessful. By the end of the day, General Erasmo Escala and a Chilean army of 10,000 were ashore and moving inland, isolating the province of Tarapacá from the rest of Peru and cutting off General Juan Buendía's 1st Southern Army from reinforcements.

Marching south towards the city of Iquique with 6,000 troops, the Chileans held off a sudden 7,400-strong Allied counterattack at the Battle of San Francisco on 19 November, with high casualties to both sides. The Bolivian force, possessed of weak leadership, withdrew during the battle, forcing the Peruvians to retreat to the city of Tarapacá. Four days later, the Chilean army captured Iquique with little resistance.

Escala sent a detachment of 3,600 soldiers, cavalry and artillery to wipe out the rest of the Peruvian forces, estimated at fewer than 2,000 poorly trained and demoralized men. The Battle of Tarapacá, on 27 November, took place as the Chilean attack found the Peruvian forces in better morale and at almost double the number expected. Led by Colonel Andrés Cáceres, the Peruvian army routed the Chilean expedition, which left behind significant quantities of supplies and ammunition. The Peruvian victory at Tarapacá would have little impact on the war. General Buendía's army, down to 4,000, retreated further north to Arica by 18 December.

A new Chilean expedition left Pisagua and on 24 February 1880 disembarked nearly 12,000 soldiers at Pacocha Bay (near Ilo). Commanded by General Manuel Baquedano, this force isolated the provinces of Tacna and Arica, destroying any practical hope for reinforcements from Peru. On the outskirts of Tacna combatants from the three contending countries met on what would later be known as the Battle of El Alto de la Alianza. Commanding the allied army was Narciso Campero, the Bolivian president. In the subsequent carnage Chilean artillery proved superior, and as a result most of Peru's professional army was destroyed. After the battle Bolivia withdrew completely from the war.

On 7 June, some 4,000 Chilean forces backed by the Navy successfully attacked a Peruvian garrison in Arica, which was under the command of Colonel Francisco Bolognesi. Chilean forces, directed by Colonel Pedro Lagos, had to run up the Morro de Arica (a steep and tall seaside hill) facing 2,000 Peruvian troops.

The assault became known as the Battle of Arica, which turned out to be one of the most tragic and, at the same time, most emblematic events of the war: Chile suffered 479 mortal casualties, while almost 900 Peruvians lost their lives, including Colonel Bolognesi. This battle was especially bloody since most Chileans died because of landmines; and with bullets running low most of the Peruvian deaths were at the hands of Corvo-wielding Chileans. The multiple cuts on the corpses made many speculate that the execution of prisoners had taken place, but most authors say that the captains were actually holding back the enraged Chileans to prevent the deaths of routed soldiers.[9]

Other high ranking Peruvian officers who also perished were Colonel Alfonso Ugarte, Colonel Mariano Bustamante and his Chief of Detail. These three Peruvian officers belonged to the group that, on the eve of battle, had gallantly rejected an offer to deliver the doomed garrison to the Chileans in an honourable surrender; Colonel Bolognesi bore out his famous vow to the Chilean emissary that he would defend Arica "to the last cartridge." Bolognesi vow goes as: "Tengo deberes sagrados que cumplir y los cumpliré hasta quemar el último cartucho." ("I have sacred duties to fulfill, and I will fulfill them until I fire the last round"). The expression "hasta quemar el último cartucho" ("Until the last round is fired") has passed into the Spanish language.

Since the Morro de Arica was the last bulwark of defence for the allied troops standing in the city, its occupation by Chile has been of utmost historical relevance for both countries.

In October 1880, the United States unsuccessfully mediated in the conflict aboard USS Lackawanna at Arica Bay, attempting to end the war through diplomacy. Representatives from Chile, Peru, and Bolivia met to discuss the territorial disputes; yet both Peru and Bolivia rejected the loss of their territories to Chile and abandoned the conference.

19 November 1880 the Chilean army landed in Pisco, and by January 1881, the Chileans were marching towards the Peruvian capital, Lima.

Regular Peruvian forces together with poorly armed people, set up to defend Lima. However, Peruvian forces were defeated in the battles of San Juan and Miraflores, and Lima fell in January 1881 to the forces of General Baquedano. The southern suburbs of Lima, including the upscale beach area of Chorrillos, were looted and every inhabitant was forced to surrender valuables or suffer a bitter end. This desperate order was issued to raise money to pay the late wages of the Chilean soldiers and prevent an uprising.

The outlying haciendas were burned down by Chinese coolies who had been brought in from southern China since the early 1850s as cheap labour for the haciendas.

Occupation of Peru

With little effective Peruvian central government remaining, Chile pursued an ambitious campaign throughout Peru, especially along the coast and in the central Sierra, penetrating as far north as Cajamarca. Even in these circumstances, Chile was not able to completely subjugate Peru. During the occupation of Lima, Chilean troops pillaged Peruvian public buildings, turned the old University of San Marcos into a barracks, raided medical schools and other institutions of education, and stole a series of monuments and artwork that had adorned the city.[10] As war booty, Chile confiscated the contents of the Peruvian National Library in Lima and transported thousands of books (including many centuries-old original Spanish, Peruvian and Colonial volumes) to Santiago de Chile, along with much capital stock. These books were partially returned (4000 of 30,000) to the Peru in November of 2007.[11]

Peruvian resistance continued for three more years, with apparent U.S. encouragement. The leader of the resistance was General Andrés Cáceres (nicknamed the Warlock of the Andes), who would later be elected president of Peru. Under his intelligent leadership, Peruvian militia forces inflicted painful defeats upon the Chilean army in the battles of Pucara, Marcavalle and Concepcion. However, after a substantial defeat Battle of Huamachuco, there was little further resistance. Finally, on 20 October 1883, Peru and Chile signed the Treaty of Ancón, by which Peru's Tarapacá province was ceded to the victor; on its part, Bolivia was forced to cede Antofagasta.

Characteristics of the War

Strategic control of the sea

The theatre of war between 1879 and 1881 was a large expanse of desert, sparsely populated and far removed from major cities or resources; it is, however, close to the Pacific Ocean. It was clear from the beginning that control of the sea would be the key to an inevitably difficult desert war: supply by sea, including water, food, ammunition, horses, fodder and reinforcements, was quicker and easier than marching supplies through the desert or across the Bolivian high plateau.

While the Chilean Navy started an economic and military blockade of the Allies' ports, Peru took the initiative and utilized its smaller but effective navy as a raiding force. Chile was forced to delay the ground invasion for six months, and to shift its fleet from blockading to hunting Huáscar until she was captured.

With the advantage of naval supremacy, Chilean ground strategy focused on mobility: landing ground forces in enemy territory in order to raid Allied ground assets; landing in strength to split and drive out defenders and leaving garrisons to guard territory as the war moved north. Peru and Bolivia fought a defensive war: maneuvering along long overland distances; relying where possible on land or coastal fortifications with gun batteries and minefields; coastal railways were available to Peru, and telegraph lines provided a direct line to the government in Lima. When retreating, Allied forces made sure that little if any assets remained to be used by the enemy.

Sea mobile forces proved to be, in the end, an advantage for desert warfare on a long coastline. Defenders found themselves hundreds of kilometers away from home; invading forces were usually a few kilometers away from the sea.

Occupation, resistance and attrition

The occupation of Peru between 1881 and 1884 was a different story altogether. The war theatre was the Peruvian Sierra, where Peruvian resistance had easy access to population, resource and supply centres further from the sea; it could carry out a war of attrition indefinitely. The Chilean army (now turned occupation force) was split into small garrisons across the theatre and could devote only part of its strength to hunting down rebels without a central authority.

After a costly occupation and prolonged anti-insurgency campaign, Chile sought to achieve a political exit strategy. Rifts within Peruvian society provided such an opportunity after the Battle of Huamachuco, and resulted in the peace treaty that ended the occupation.

Participation of Chinese immigrants

According to Hong Kong Asia Television programme "Stories of Chinese Afar III", there were about 2000 Chinese that participated on the Chilean side after being freed from slavery by Chilean troops in their advance through Peruvian territory. Their roles were spoofing as working with the Peruvians to acquire intelligence, act as back-end support or to initiate a sudden attack to the Peruvian army during Lynch's Expedition.

Technology

The war saw the use by both sides of new, or recently introduced, late 19th century military technology such as breech-loading rifles & cannons, remote-controlled land mines, armor-piercing shells, naval torpedoes, torpedo boats, and purpose-built landing craft.

The second-generation of ironclads (i.e. designed after the Battle of Hampton Roads) were employed in battle for the first time. That was significant for a conflict where a major power was not directly involved, and it drew the attention of British, French, and U.S. observers of the war.

During the war, Peru developed the Toro Submarino ("Submarine Bull"). Though completely operational, she never saw action, and she was scuttled at the end of the war to prevent her capture by Chilean forces.

Aftermath

Peace terms

Under the terms of the Treaty of Ancón,[2] Chile was to occupy the provinces of Tacna and Arica for 10 years, after which a plebiscite was to be held to determine nationality. The two countries failed for decades to agree on the terms of the plebiscite. Finally in 1929, through the mediation of the United States under President Herbert Hoover, an accord was reached by which Chile kept Arica. Peru reacquired Tacna and received a $6 million indemnity payment and other concessions.

In 1884, Bolivia signed a truce that gave control to Chile of the entire Bolivian coast, the province of Antofagasta, and its valuable nitrate, copper, and other mineral deposits, and a further treaty in 1904 made this arrangement permanent. In return, Chile agreed to build a railroad connecting the capital city of La Paz, Bolivia with the port of Arica, and Chile guaranteed freedom of transit for Bolivian commerce through Chilean ports and territory.

Bolivia has also negotiated treaties of commercial access to the oceans via Brazil, Argentina, etc.

Long-term consequences

The War of the Pacific left traumatic scars on all societies involved in the conflict. For Bolivians, the loss of the territory which they refer to as the Litoral (the coast) remains a deeply emotional issue and a practical one, as was particularly evident during the internal natural gas riots of 2004. Popular belief attributes much of the country's problems to its landlocked condition; accordingly, recovering the seacoast is seen as the solution to most of these difficulties. However, the real issue is the fear of being dependent on Chile or Peru. In 1932, this was a contributing factor in the failed Chaco War with Paraguay, over territory controlling access to the Atlantic Ocean through the Paraguay River. In recent decades, all Bolivian Presidents have made it their policy to pressure Chile for sovereign access to the sea. Diplomatic relations with Chile have been severed since 17 March 1978, in spite of considerable commercial ties. Currently, the leading Bolivian newspaper "El Diario" [3] still features at least a weekly editorial on the subject.

Peruvians developed a cult for the heroic defenders of the patria (nation, literally fatherland), such as Admiral Miguel Grau Seminario, Colonel Francisco Bolognesi, Colonel Alfonso Ugarte, who were killed in the war, and General Andrés Avelino Cáceres who went on to become a leading political figure and symbol of resistance to the occupying Chilean Army. Peruvian heroes of the war are buried in the "Cripta de los Héroes" in Presbítero Maestro cemetery in Lima, Peru. This mausoleum is the largest in the cemetery, and its entrance reads "La Nación a sus Defensores" (From the nation, to its defenders). The defeat engendered a deep revenge desire among the ruling classes, which also led to a skewed view of the role of the armed forces; this attitude dominated society throughout the 20th century. War honors are also held to Vice Admiral Abel-Nicolas Bergasse Dupetit Thouars, French commander, that after the Battle of Miraflores, he prevented the destruction and looting of Lima by threatening to engage and destroy the Chilean Navy with a French naval force under his command.

Chile fared better, gaining a lucrative territory with major sources of income, including nitrates, saltpeter and copper. The national treasury grew by 900% between 1879 and 1902 due to taxes coming from the newly acquired Bolivian and Peruvian lands. [12]Victory was, however, a mixed blessing. During the war Chile waived most of its claim over the Patagonia in 1881, in order to ensure Argentina's neutrality; Chilean popular belief sees this as a territorial loss of almost half a million square miles. British involvement and control of the nitrate industry rose significantly after the war,[13] leading them to meddle in Chilean politics and ultimately to back an overthrow of the Chilean President in 1891. High nitrate profits lasted for only a few decades and fell sharply once synthetic nitrates were developed during World War I. This led to a massive economic breakdown (known as the nitrate crisis), since many industrial factories around the country had closed in the early 1880s to free up labor for the then rising and now dead extraction business, dramatically slowing the country's industrial development. When the saltpeter mines closed or proved no longer profitable, the British companies left the country, leaving a large number of unemployed behind. Currently, the former Bolivian region is still the world's richest source of copper and its ports move trade between nearby countries and the Pacific Ocean; the former Peruvian region faces more problematic issues since no new sources of richness have been discovered since the Nitrate Crisis, but at least on 28 August 1929, Chile returned the province of Tacna to Peru[4], where a large copper mine was later discovered.

The war consolidated the Chilean navy as an institution, just as the War of Independence and the 1836 War against the Santa Cruz confederation consolidated the Chilean Army. After many years in which it had been considered an unimportant item on Chilean budget, the Navy gained an important squadron and became a significant power on the Pacific Ocean, with the addition of the cruiser Esmeralda, the fastest warship of its time. A strong class of naval officials also emerged from the war, most of them descendants of immigrants and not related to Santiago's circle of power. This class played a role in the plot against the President José Manuel Balmaceda in 1891 when the Chilean navy defeated the army of Chile.

In 1999, Chile and Peru at last agreed to complete the implementation of the last parts of the Treaty of Lima, providing Peru with a port in Arica. [14]

Prominent military commanders

Bolivia

- Mr. Eduardo Abaroa †, an engineer, was killed leading a group of civilian defenders at the Battle of Topater

- Dr. Ladislao Cabrera, organizing the defense of Calama

- General Narciso Campero, military President of Bolivia (1880-1884)

- General Hilarión Daza, military President of Bolivia (1876-1879)

Chile

- General Manuel Baquedano González, commander in chief of the Chilean Army

- Captain Ignacio Carrera Pinto †, killed with the entire garrison at the Battle of La Concepción, Peru

- Colonel Pedro Lagos Marchant, captured the Morro de Arica (Arica Cape)

- Rear Admiral Patricio Lynch y Solo de Zaldívar, military Governor of occupied Peru

- Captain Arturo Prat Chacón †, was killed on the Huáscar at the Naval Battle of Iquique. He jumped from "La Esmeralda" and landed in the "Huascar". He died with a bullet wound in his head.

Peru

- Colonel Francisco Bolognesi †, was killed while leading the defense of the Arica garrison

- General Andrés Cáceres, led the guerilla war during the occupation of Peru, was elected President of Peru after the war

- Rear Admiral Miguel Grau †, commander of Huáscar and widely known as the gentleman of the seas, was killed at the Naval Battle of Angamos

- Colonel Leoncio Prado †, the son of former President Mariano Ignacio Prado, chose duty as a soldier over an oath not to fight, was captured and executed by a Chilean firing squad after the Battle of Huamachuco

- Colonel Alfonso Ugarte †, Bolognesi's top lieutenant, a rich saltpeter entrepreneur and former mayor of Iquique, was killed during the Battle of Arica, believed to have jumped off a cliff on his horse to save the flag from capture.

Other nationalities

- Rear Admiral Abel Bergasse Dupetit-Thouars, French commander, after the Battle of Miraflores, he prevented the destruction and looting of Lima by threatening to engage and destroy the Chilean Navy with a French naval force under his command.

- Colonel Robert Souper Howard †, a British soldier who served in the Chilean Army in nearly every battlefield of the war, was killed at the Battle of San Juan.

- Lt. Colonel Roque Saenz Peña, an Argentine lawyer who served as an officer in the Peruvian Army during the battles of Tarapaca and Arica, was later elected President of Argentina.

See also

- History of Bolivia

- History of Chile

- History of Peru

- Atacama border dispute

- Tacna-Arica compromise

- War of the Confederation

- Chincha Islands War

- Chilean-Peruvian Maritime Dispute of 2006--2007

- Chile-Peru relations

References

- ↑ The map also shows some parts of Atacama that were ceded to Argentina in 1899

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tratado de límites de 1866 entre Bolivia y Chile (Spanish)

- ↑ St. John, Ronald B.; C.H. Schofield. The Bolivia-Chile-Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert

- ↑ Defensive alliance treaty of 1873 between Bolivia and Peru (Tratado de alianza defensiva de 1873 entre Bolivia y Perú (Spanish))

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/2510820?seq=6

- ↑ Crow, The Epic of Latin America, p. 182-183

- ↑ Jorge Basadre, Historia de la República del Perú, vol. VI, p. 40.

- ↑ Actual number of casualties taken from http://www.soberaniachile.cl/norte3_6.html (in spanish)#sub11

- ↑ {{cite news|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=OvYtAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA690&lpg=PA690&dq=Chile+destroyed+Lima&source=web&ots=NYWbeGRm5E&sig=fqU3QDhDg_ClzJ37DR5XIHV9uBI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result|title=Encyclopedia Brittanica: Lima|publisher=Google Books|author=Hugh Chisholm|accessdate=2008-12-04}

- ↑ Dan Collyns. "Chile returns looted Peru books", BBC. Retrieved on 2007-11-10.

- ↑ Crow, The Epic of Latin America, p. 180

- ↑ Foster, John B. & Clark, Brett. (2003). "Ecological Imperialism: The Curse of Capitalism" (accessed September 2 2005). The Socialist Register 2004, p190-192. Also available in print from Merlin Press.

- ↑ Domínguez, Jorge et al. 2003 Boundary Disputes in Latin America. United States Washington, D.C.: Institute of Peace.

External links

- South American Military History

- The United States and the Bolivian Seacoast Online book by Bolivian historian and diplomat Jorge Gumucio Granier

- Clear brief account of causes and consequences of the War of the Pacific, 1879-1883.

- (Spanish) La Guerra del Pacífico, Los Héroes Olvidados Chilean site

- History of Chemical Engineering: Nitrogen, for a brief description nitrates and its strategic importance

- (Spanish) Sin mar… hace 127 años ("Without Sea… for 127 years"); page about the war and its impact on Bolivian society.

- Article: Bolivia Reaches for a Slice of the Coast That Got Away - NY Times 9/24/06

|

||||||||||||||