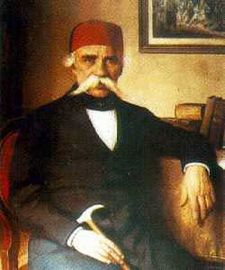

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić

| Vuk Stefanović Karadžić | |

|

|

| Born | November 7, 1787 Tršić, Ottoman Empire |

|---|---|

| Died | February 7, 1864 (aged 76) Vienna, Austrian Empire |

| Occupation | Linguist |

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić (Serbian Cyrillic: Вук Стефановић Караџић) (November 7, 1787 - February 7, 1864) was a Serbian linguist and major reformer of the Serbian language.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Karadžić was born to parents Stefan and Jegda (maiden Zrnić) in the village of Tršić, near Loznica in Serbia, which was then still a part of the Ottoman Empire. His family had a low infant survival rate and he was thus named Vuk ('wolf') so that witches and evil spirits would not hurt him. His family were members of the Drobnjaci tribe and came to Tršić from Petnjica, Montenegro.

Education

He was taught how to read and write by his cousin Jevta Savić, who was the only literate person in the region. He continued his education in Loznica, and later in the monastery of Tronoša. Because he was not taught anything in the monastery, but was made to pasture the livestock instead, his father brought him back home. After unsuccessful attempts to enroll him in the gymnasium at Sremski Karlovci, for which 19 year-old Karadžić was too old, Karadžić left for Petrinje where he spent a few months learning German. Later, he left for Belgrade, in order to meet his beloved Enlightenment scholar Dositej Obradović, who rudely fended him away. Disappointed, Karadžić left for Jadar and began working as a scribe for Jakov Nenadović. After the opening of the Velika škola school in Belgrade, Karadžić becomes one of its first pupils.

Later life and death

Soon after, he grew ill and left for medical treatment in Pest and Novi Sad, but was unable to get treatment for his sick leg. Lame, Karadžić returned to Serbia, and after the unsuccessful rebellion in 1813 left for Vienna where he met Jernej Kopitar who helped him carry out his goals of reforming the Serbian language and its orthography. Due to conflicts with Miloš Obrenović I, Prince of Serbia, Karadžić was forbidden to publish books in Serbia and Austria, but managed to get help in Russia where he also received a full pension in 1826. His only surviving child was his daughter, Mina Karadžić. He died in Vienna. His bones were relocated to Belgrade in 1897 and buried with great honours next to the grave of Dositej Obradović.

Work

Linguistic reforms

As one of the leading European philologists of his time, Karadžić reformed the Serbian literary language and standardized the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by following strict phonemic principles on the German model. Karadžić's reforms of the Serbian literary language modernized it and distanced it from Serbian and Russian Church Slavonic, instead bringing it closer to common folk speech, specifically, to the dialect of Eastern Herzegovina which he spoke. Karadžić was, together with Đuro Daničić, the main Serbian signatory to the Vienna Agreement of 1850 which, encouraged by Austrian authorities, laid the foundation for the Serbian language, various forms of which are used by Serbs in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia today. Karadžić also translated the New Testament into Serbian, which was published in 1868.

Literature

In addition to his linguistic reforms, Karadžić also made great contributions to folk literature, using peasant culture as the foundation. Because of his peasant upbringing, he closely associated with the oral literature of the peasants, compiling it to use in his collection of folk songs, tales, and proverbs. While Karadžić hardly considered peasant life romantic, he highly regarded it as an integral part of Serbian culture. He collected several volumes of folk prose and poetry, including a book of over 100 lyrical and epic songs learned as a child and written down from memory. He also published the first dictionary of vernacular Serbian. For his work he received little financial aid, at times living in poverty.

Major works

- Primer of the Serbian language (1814)

- Dictionary of the Serbian language (1st ed. 1818, 2nd ed. 1852)

- New Testament (translation into Serbian) (1st partial ed.1824, 1st complete ed. 1847, 2nd ed. 1857)

- Serbian folk tales (1821, 1853, 1870 and more)

- Serbian folk poems, vol. 1 (1841)

- Serbian epic poetry (1845 and more)

- Deutsch-Serbisches Wörterbuch (German-Serbian Dictionary) 1872

- Biography of hajduk Veljko Petrović (Житије Хајдук-Вељка Петровића)

Quotes

Write as you speak and read as it is written. (The essence of modern Serbian spelling)

In Serbian: Пиши као што говориш и читај како је написано. (Piši kao što govoriš i čitaj kako je napisano.)

Although the above quotation is usually attributed to Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, it is in fact an orthographic principle devised by the German grammarian and philologist Johann Christoph Adelung. Karadžić merely used that principle to push through his language reform (as stated in the book The Grammar of the Serbian Language by Ljubomir Popović).

The attribution of the quote to Karadžić is a common misconception in Serbia. Due to that fact, the entrance exam to the Faculty of Philology of the University of Belgrade (Serbia) occasionally contains a question on the authorship of the quote (as a sort of trick question).

Further reading

- Wilson, Duncan (1970). The Life and Times of Vuk Stefanović Karadzić, 1787-1864; Literacy, Literature and National Independence in Serbia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

- Biography (Serbian)

- Encyclopedia of World Bigraphy from Bookrags.com (English)

- Works by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić at Project Gutenberg Europe

- Vuk's Foundation (Serbian)

- Vuk Karadžić online library (at Project Rastko) (Serbian)