Thiamin

| Thiamin | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

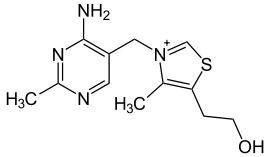

| IUPAC name | 2-[3-[(4-amino-2-methyl- pyrimidin-5-yl)methyl]- 4-methyl-thiazol-5-yl] ethanol |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 59-43-8 |

| PubChem | |

| MeSH | |

| SMILES |

|

| ChemSpider ID | |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C12H17N4OS+ |

| Molar mass | 265.356 |

| Melting point |

248-260 °C (hydrochloride salt) |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

- For the similarly spelled pyrimidine, see Thymine

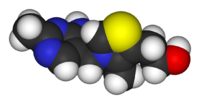

Thiamin or thiamine, also known as vitamin B1 and aneurine hydrochloride, is the term for a family of molecules sharing a common structural feature responsible for its activity as a vitamin. It is one of the B vitamins. Its most common form is a colorless chemical compound with a chemical formula C12H17N4OS. This form of thiamin is soluble in water, methanol, and glycerol and practically insoluble in acetone, ether, chloroform, and benzene. Another form of thiamin known as TTFD has different solubility properties and belongs to a family of molecules often referred to as fat-soluble thiamins. Thiamin decomposes if heated. Its chemical structure contains a pyrimidine ring and a thiazole ring.

Thiamin is one of only four nutrients associated with a pandemic human deficiency disease. It is essential for neural function and carbohydrate metabolism. Thiamin deficiency results in beriberi, a disease characterized by a bewildering variety of symptoms. Common symptoms often involve the nervous system and the heart. In less severe deficiency, nonspecific signs include malaise, weight loss, irritability and confusion.[1]

Contents |

History

Thiamin was first discovered in 1910 by Umetaro Suzuki in Japan when researching how rice bran cured patients of beriberi. He named it aberic acid (later oryzanin). He did not determine its chemical composition, nor that it was an amine. It was first crystallized by Jansen and Donath in 1926 (they named it aneurin, for antineuritic vitamin). Its chemical composition and synthesis was finally reported by Robert R. Williams in 1935. He also coined the current name for it, thiamin.

Sources

Thiamin is found in a wide variety of many foods at low concentrations. Yeast and liver are the most highly concentrated sources of thiamin. Cereal grains, however, are the most important dietary sources of thiamin in the diet as these foods are consumed readily in most diets. Of the cereal grains, whole grains contain more thiamin than refined grains. Thiamin is found in the outer layers of the grain as well as the germ. During the refining process these segments of the grain are removed therefore decreasing the thiamin content in products such as white rice and white bread. For example, 100 g of whole wheat flour contains 0.55 mg of thiamin while 100 g of white flour only contains 0.06 mg of thiamin. In addition to cereal grains some vegetables and meats are also good sources of thiamin. Listed below are foods rich in thiamin.[2]

- Yeast

- Oatmeal

- Brown rice

- Whole grain flour (rye or wheat)

- Asparagus

- Kale

- Cauliflower

- Potatoes

- Oranges

- Pork

- Cured ham

- Liver (beef or pork)

- Eggs

Antagonists

Thiamin in foods can be degraded in a variety of ways. Sulfites, which are added to foods usually as a preservative,[3] will attack thiamin at the methylene bridge in the structure, cleaving the pyrimidine ring from the thiazole ring.[4] The rate of this reaction is increased under acidic conditions. Thiamin can also be degraded by thiaminases. Some thiaminases are produced by bacteria. Bacterial thiaminases are cell surface enzymes that must dissociate from the membrane before being activated. The dissociation can occur in ruminants under acidotic conditions. Rumen bacteria also reduce sulfate to sulfite, therefore high dietary intakes of sulfate can have thiamin-antagonistic activities.

Plant thiamin antagonists are heat stable and occur as both the ortho and para hydroxyphenols. Some examples of these antagonists are caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid and tannic acid. These compounds interact with the thiamin to oxidize the thiazole ring, thus rendering it unable to be absorbed. Two flavonoids, quercetin and rutin, have also been implicated as thiamin antagonists.[5]

Absorption

Thiamin is released by the action of phosphatase and pyrophosphatase in the upper small intestine. At low concentrations the process is carrier mediated and at higher concentrations, absorption occurs via passive diffusion. Active transport is greatest in the jejunum and ileum. The cells of the intestinal mucosa have thiamin pyrophosphokinase activity, but it is unclear whether the enzyme is linked to active absorption. The majority of thiamin present in the intestine is in the phosphorylated form, but when thiamin arrives on the serosal side of the intestine it is often in the free form. The uptake of thiamin by the mucosal cell is likely coupled in some way to its phosphorylation/dephosphorylation. On the serosal side of the intestine, evidence has shown that discharge of the vitamin by those cells is dependent on Na+-dependent ATPase.[6]

Transport

Bound to serum proteins

The majority of thiamin in serum is bound to proteins, mainly albumin. Approximately 90% of total thiamin in blood is in erythrocytes. A specific binding protein called thiamin-binding protein (TBP) has been identified in rat serum and is believed to be a hormonally regulated carrier protein that is important for tissue distribution of thiamin.[7]

Cellular uptake

Uptake of thiamin by cells of the blood and other tissues occurs via active transport. About 80% of intracellular thiamin is phosphorylated and most is bound to proteins. In some tissues, thiamin uptake and secretion appears to be mediated by a soluble thiamin transporter that is dependent on Na+ and a transcellular proton gradient. The highest concentration of the transporter have been found in skeletal muscle, heart, and placenta.[8]

Tissue Distribution

Human storage of thiamin is about 25 to 30 mg with the greatest concentrations in skeletal muscle, heart, brain, liver, and kidneys. Thiamin monophosphate(TMP) and free thiamin is present in plasma, milk, cerebrospinal fluid, and likely all extracellular fluids. Unlike the highly phosphorylated forms of thiamin, TMP and free thiamin are capable of crossing cell membranes. Thiamin contents in human tissues are less than those of other species.[9]

Deficiency

Thiamin deficiency can lead to myriad problems including neurodegeneration, wasting and death. A lack of thiamin can be caused by malnutrition, alcoholism, a diet high in thiaminase-rich foods (raw freshwater fish, raw shellfish, ferns) and/or foods high in anti-thiamin factors (tea, coffee, betel nuts).[10]

Well-known syndromes caused by thiamin deficiency include Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and beriberi, diseases also common with chronic alcoholism.

There is only one book in English devoted entirely to the clinical use of vitamin B1. It was written by Derrick Lonsdale. According to the author, early signs of thiamin deficiency include anorexia, insomnia, sleep apnea, dementia, depression, impotence, and infertility. Extensive published research reviewed in the book provides statistically significant data supporting this position.

An important property of thiamin that distinguishes it from the other three vitamins associated with vitamin deficiency (vitamin C, vitamin B3, and vitamin D) is that it is extracted from food in the digestive tract in a form that requires specialized proteins for absorption into the bloodstream. Once in the bloodstream, this form of thiamin requires specialized proteins for distribution to cells throughout the body.

Because thiamin requires specialized transport proteins, malfunctions of these proteins can cause localized deficiency even when the diet contains more than twice the recommended daily allowance. A form of thiamin that does not require specialized transport proteins for absorption and distribution is produced commercially in Japan. It is known as TTFD. A google scholar search of "thiamin TTFD" results in over 1000 references to peer-reviewed research related to preventing and treating disease with TTFD.

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM), is the most common thiamin deficiency disorder in young ruminant and nonruminant animals. Symptoms of PEM include a profuse, but transient diarrhea, listlessness, circling movements, star gazing or opisthotonus (head drawn back over neck), and muscle tremors.[11]

It is thought that many people with diabetes have a deficiency of thiamin and that this may be linked to some of the complications that can occur.[12][13]

Alcoholic Brain Disease[14]

Thiamin and thiamin-using enzymes are present in all cells of the body, thus, a thiamin deficiency would seem to adversely affect all of the organ systems. However, the nervous system (and heart) shows particular sensitivity to the effects of a thiamin deficiency at the cellular level.

Nerve cells and other supporting cells (such as glial cells) of the nervous system require thiamin. Examples of neurologic disorders that are linked to alcohol abuse include Wernicke’s encephalopathy (Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome) and Korsakoff’s psychosis (alcohol amnestic disorder) as well as varying degrees of cognitive impairment.

How does alcoholism induce thiamin deficiency? The enzymes transketolase, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) all require thiamin as a cofactor in order to function in carbohydrate metabolism. Therefore, a thiamin deficiency would be detrimental to the functionality of these enzymes. Transketolase is important in the pentose phosphate pathway. PDH and α-KGDH function in biochemical pathways that result in the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is a major form of energy for the cell. PDH is also needed for the production of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, and for myelin synthesis. During metabolism, PDH determines whether the process is aerobic or anaerobic, and α-KGDH is responsible for determining the rate of the citric acid cycle.

What are the mechanisms of alcohol-induced thiamin deficiency? 1) Inadequate nutritional intake: Alcoholics tend to intake less than the recommended amount of thiamin, however it is also seen that others have an extremely high level of free thiamin, suggesting an inability of these individuals to convert thiamin to the biologically active, phosphorylated form. 2) Decreased uptake of thiamin from the GI tract: Active transport of thiamin into the enterocyte occurs mostly in conditions of low thiamin concentration. The absorption is disturbed during acute alcohol exposure as illustrated by less thiamin being converted into the phosphate-containing form, suggesting a dysfunction of the enzyme responsible for this transformation: thiamin diphosphokinase. 3) Impaired thiamin utilization: Magnesium, which is required for the binding of thiamin to thiamin-using enzymes within the cell, is also deficient due to chronic alcohol consumption. The inefficient utilization of any thiamin that does reach the cells will further exacerbate the thiamin deficiency.

Following improved nutrition and the removal of alcohol consumption, some impairments linked with thiamin deficiency are reversed; particularly poor brain functionality.

Thiamin deficiency in poultry

As most feedstuffs used in poultry diets contain enough quantities of vitamins to meet the requirements in this species, deficiencies in this vitamin does not occur with commercial diets. This was, at least, the opinion in the 1960s. [15]

Mature chickens show signs 3 weeks after being fed a deficient diet. In young chicks, it can appear before 2 weeks of age.

Onset is sudden in young chicks. There is anorexia and an unsteady gait. Later on, there are locomotor signs, beginning with an apparent paralysis of the flexor ot the toes. The characteristic position is called "stargazing", meaning a chick "sitting on its hocks and the head in opisthotonos.

Response to administration of the vitamin is rather quick, occurring a few hours later. [16]

The disease is described more carefully here

Differential diagnosis include riboflavin deficiency and avian encephalomyelitis. In riboflavin deficiency, the "curled toes" is a characteristic symptom. Muscle tremor is typical of avian encephalomyelitis. A therapeutic diagnosis can be tried by supplementing Vitamin B1 only in the affected bird. If the animals do not respond in a few hours, Vitamin B1 deficiency can be excluded.

Cerebrocortical necrosis in ruminants

Polioencephalomalacia is a common condition seen in young cattle, sheep, goats, deer and camelids in association with thiamin deficiency. The most common cause is high-carbohydrate feeds, leading to the overgrowth of thiaminase-producing bacteria, but dietary ingestion of thiaminase (e.g. in Bracken fern) or inhibition of thiamin absorption by high sulphur intake are also possible.[17]

Diagnostic testing

A positive diagnosis test for thiamin deficiency can be ascertained by measuring the activity of the enzyme transketolase in erythrocytes. Thiamin can also be seen directly in whole blood following the conversion of thiamin to a fluorescent thiochrome derivative. However, this test may not reveal the deficiency in diabetic patients.[12][18]

Thiamin phosphate derivatives

There are four known natural thiamin phosphate derivatives: thiamin monophosphate (ThMP), thiamin diphosphate (ThDP) or thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP), thiamin triphosphate (ThTP), and the recently discovered adenosine thiamin triphosphate (AThTP).

Thiamin pyrophosphate

Thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP), also known as thiamin diphosphate (ThDP) or cocarboxylase, is a coenzyme for several enzymes that catalyze the dehydrogenation (decarboxylation and subsequent conjugation to Coenzyme A) of alpha-keto acids. Examples include:

- In mammals:

- pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (metabolism of carbohydrates)

- branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase

- 2-hydroxyphytanoyl-CoA lyase

- transketolase (functions in the pentose phosphate pathway to synthesize NADPH and the pentose sugars deoxyribose and ribose )

TPP is synthesized by the enzyme thiamin pyrophosphokinase, which requires free thiamin, magnesium, and adenosine triphosphate.

Thiamin triphosphate

Thiamin triphosphate (ThTP) was long considered a specific neuroactive form of thiamin. However, recently it was shown that ThTP exists in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals suggesting a much more general cellular role. In particular in E. coli it seems to play a role in response to amino acid starvation.

Adenosine thiamin triphosphate

Adenosine thiamin triphosphate (AThTP) or thiaminylated adenosine triphosphate has recently been discovered in Escherichia coli where it accumulates as a result of carbon starvation. In E. coli, AThTP may account for up to 20 % of total thiamin. It also exists in lesser amounts in yeast, roots of higher plants and animal tissues.

Genetic diseases

Genetic diseases of thiamin transport are rare but serious. Thiamin Responsive Megaloblastic Anemia with diabetes mellitus and sensorineural deafness (TRMA)[19] is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the gene SLC19A2,[20] a high affinity thiamin transporter. TRMA patients do not show signs of systemic thiamin deficiency, suggesting redundancy in the thiamin transport system. This has led to the discovery of a second high affinity thiamin transporter, SLC19A3.[21][22]

Research

High doses

The RDA in most countries is set at about 1.4 mg. However, tests on volunteers at daily doses of about 50 mg have claimed an increase in mental acuity.[23]

Thiamin as an insect repellent

Some old studies suggested that the ingestion of large doses of thiamin (25 to 50 mg three times per day) could be effective as an oral insect repellent against mosquito bites.[24] However, there is now conclusive evidence that thiamin has no efficacy against mosquitoe bites. [25] [26] [27] [28]

Autism

A 2002 pilot study administered thiamin tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide (TTFD) rectally to ten autism spectrum children, and found beneficial clinical effect in eight.[29] There have been no follow-up trials.

References

- ↑ Combs,G. F. Jr. The vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 3rd Edition. Ithaca, NY: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008; pg.266

- ↑ Combs GF. The vitamins: fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. 3rd Ed. Elsevier: Boston, 2008.

- ↑ McGuire, M. and K.A. Beerman. Nutritional Sciences: From Fundamentals to Foods. 2007. California: Thomas Wadsworth.

- ↑ Combs, G.F. The Vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 2008. San Diego: Elsevier

- ↑ Combs, G.F. The Vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 2008. San Diego: Elsevier

- ↑ Combs,G. F. Jr. The vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 3rd Edition. Ithaca, NY: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008; pg.268

- ↑ Combs,G. F. Jr. The vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 3rd Edition. Ithaca, NY: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008

- ↑ Combs,G. F. Jr. The vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 3rd Edition. Ithaca, NY: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008

- ↑ Combs,G. F. Jr. The vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 3rd Edition. Ithaca, NY: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008

- ↑ "Thiamin", Jane Higdon, Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute

- ↑ National Research Council. 1996. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, Seventh Revised Ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Thornalley PJ (2005). "The potential role of thiamine (vitamin B(1)) in diabetic complications". Curr Diabetes Rev 1 (3): 287–98. PMID 18220605.

- ↑ Diabetes problems 'vitamin link', BBC News, Tuesday, 7 August 2007

- ↑ Martin, PR, Singleton, CK, Hiller-Sturmhofel, S (2003). "The role of thiamin deficiency in alcoholic brain disease" Alcohol Research and Health. 27:134-142

- ↑ Merck veterinary manual, ed 1967, pp 1440-1441.

- ↑ R.E. Austic and M.L. Scott, Nutritional deficiency diseases, in "Diseases of poultry, ed. by M.S. Hofstad, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, USA ISBN 0-8138-0430-2, p. 50.

- ↑ http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/102000.htm.

- ↑ Researchers find vitamin B1 deficiency key to vascular problems for diabetic patients, University of Warwick

- ↑ Thiamine Responsive Megaloblastic Anemia with severe diabetes mellitus and sensorineural deafness (TRMA) PMID 249270

- ↑ SLC19A2 PMID 603941

- ↑ SLC19A3 PMID 606152

- ↑ Online 'Mendelian Inheritance in Man' (OMIM) 249270

- ↑ Thiamine's Mood-Mending Qualities, Richard N. Podel, Nutrition Science News, January 1999.

- ↑ Pediatric Clinics of North America, 16:191, 1969

- ↑ BMJ Clinical Evidence

- ↑ Ives AR, Paskewitz SM (2005). "Testing vitamin B as a home remedy against mosquitoes". J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 21 (2): 213-217. PMID 16033124. http://apt.allenpress.com/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1043%2F8756-971X(2005)021%5B0213%3ATVBAAH%5D2.3.CO%3B2&ct=1.

- ↑ Khan AA, Maibach HI, Strauss WG, Fenley WR. (2005). "Vitamin B1 is not a systemic mosquito repellent in man". Trans. St. Johns Hosp. Dermatol. Soc. 55 (1): 99-102. PMID 4389912.

- ↑ Strauss WG, Maibach HI, Khan AA (1968). "Drugs and disease as mosquito repellents in man". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 17 (3): 461-464. PMID 4385133.

- ↑ Lonsdale D, Shamberger RJ, Audhya T (2002). "Treatment of autism spectrum children with thiamin tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide: a pilot study" (PDF). Neuro Endocrinol. Lett 23 (4): 303–8. PMID 12195231. http://www.nel.edu/pdf_w/23_4/NEL230402A02_Lonsdale_rw.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-08-10.

External links

- "Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism" at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Thiamin deficiency in poultry

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||