Vice President of the United States

| Vice President of the United States |

|

Official seal |

|

| Style | Mister Vice President |

|---|---|

| Residence | Number One Observatory Circle |

| Inaugural holder | John Adams |

| Formation | April 20, 1789 |

| Succession | First |

The Vice President of the United States[1] is the first person in the presidential line of succession, becoming the new President of the United States upon the death, resignation, or removal of the president. Additionally, the Vice President also serves as the President of the Senate, but only has the ability to break tie votes in that chamber.[2] In recent times, the President has assigned the Vice President additional duties that fall outside the Vice President's constitutional duties. The Vice President, however, only performs such duties as an agent of and at the discretion of the President.[3]

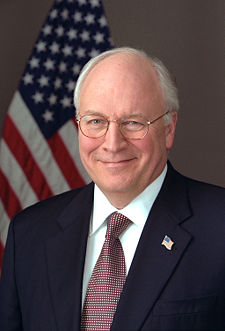

The current Vice President is Dick Cheney, whose second term expires noon on January 20, 2009. His expected successor is Joe Biden, who was elected Vice President in the 2008 presidential election.

Contents |

Eligibility

The Twelfth Amendment states that "no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States."[4] Thus, to serve as Vice President, an individual must:

- Be a natural born U.S. citizen;

- Not be younger than 35 years old; and

- Have lived in the U.S. for at least 14 years [5]

Under the Twenty-second Amendment, the President of the United States may not be elected to more than two terms. Scholars dispute whether a former President barred from election to the Presidency is also ineligible to be elected Vice President.[6][7] However, there is no similar such limition as to how many times one can be elected Vice President.

Oath

Unlike the president, the United States Constitution does not specify an oath of office for the Vice President. Several variants of the oath have been used since 1789; the current form, which is also recited by Senators, Representatives and other government officers, has been used since 1884:

| “ | I, A— B—, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.[8] | ” |

Election of the Vice President

Original Constitution and reform

Under the original terms of the Constitution, the members of the U.S. Electoral College voted only for office of President rather than for both President and vice President. Each elector was allowed to vote for two people for the top office. The person receiving the greatest number of votes (provided that such a number was a majority of electors) would be president, while the individual who received the next largest number of votes became Vice President. If no one received a majority of votes, then the U.S. House of Representatives would choose among the five highest vote-getters, with each state getting one vote. In such a case, the person who received the highest number of votes but was not chosen president would become Vice President. In the case of a tie for second, then the U.S. Senate would choose the Vice president.[5]

The original plan, however, did not foresee the development of political parties and their adversarial role in the government. In the election of 1796, for instance, Federalist John Adams came in first, but because the federalist electors split their second vote amongst several vice presidential candidates, Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson came second. Thus, the president and Vice President were from opposing parties. Predictably, Adams and Jefferson clashed over issues such as states' rights and foreign policy.[9]

A greater problem occurred in the election of 1800, in which the two participating parties each had a secondary candidate they intended to elect as Vice President, but the more popular Democratic-Republican party failed to execute that plan with their electoral votes. Under the system in place at the time (Article Two, Section 1, Clause 3), the electors could not differentiate between their two candidates, so the plan had been for one elector to vote for Thomas Jefferson but not for Aaron Burr, thus putting Burr in second place. This plan broke down for reasons that are disputed, and both candidates received the same number of votes. After 35 deadlocked ballots in the U.S. House of Representatives, Jefferson finally won on the 36th ballot and Burr became Vice President.[10]

This tumultuous affair led to the adoption of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, which directed the electors to use separate ballots to vote for the president and Vice President.[4] While this solved the problem at hand, it ultimately had the effect of lowering the prestige of the Vice Presidency, as the office was no longer for the leading challenger for the presidency.

The separate ballots for President and Vice President became something of a moot issue later in the 19th century when it became the norm for popular elections to determine a state's Electoral College delegation. Electors chosen this way are pledged to vote for a particular presidential and vice presidential candidate (offered by the same political party). So, while the Constitution says that the president and Vice President are chosen separately, in practice they are chosen together.

If no vice presidential candidate receives an Electoral College majority, then the Senate selects the Vice President, in accordance with the United States Constitution. This could in theory lead to a situation in which the incumbent Vice President - in his role as President of the Senate - would be called upon to give his tie-breaking vote for himself or his successor. The election of 1836 is the only election so far where the office of the Vice President has been decided by the Senate. During the campaign, President Martin Van Buren's running mate Richard Mentor Johnson was accused of having lived with a black woman. Virginia's 23 electors, who were pledged to Van Buren and Johnson, refused to vote for Johnson (but still voted for Van Buren). The election went to the Senate, where Johnson was elected, 33-17.

Residency limitations

The Constitution also prohibits electors from voting for both a presidential and vice presidential candidate from the same state as themselves. In theory, this might deny a vice presidential candidate with the most electoral votes the absolute majority required to secure election, even if the presidential candidate is elected, and place the vice presidential election in the hands of the Senate. In practice, this is rarely an issue, as parties avoid nominating tickets containing two candidates from the same state. In one notable case, former Wyoming congressman Dick Cheney had moved to Texas to serve as CEO of Halliburton Company, but reclaimed residency at his Wyoming home before accepting the 2000 Republican nomination for Vice President, alongside presidential nominee and Texas governor George W. Bush.

Nominating process

The vice presidential candidates of the major national political parties are formally selected by each party's quadrennial nominating convention, following the selection of the party's presidential candidates. The official process is identical to the one by which the presidential candidates are chosen, with delegates placing the names of candidates into nomination, followed by a ballot in which candidates must receive a majority to secure the party's nomination. In practice, the presidential nominee has considerable influence on the decision, and in the 20th century it became customary for that person to select a preferred running mate, who is then nominated and accepted by the convention. In recent years, with the presidential nomination usually being a foregone conclusion as the result of the primary process, the selection of a vice presidential candidate is often announced prior to the actual balloting for the presidential candidate, and sometimes before the beginning of the convention itself. Often, the presidential nominee will name a vice presidential candidate who will bring geographic or ideological balance to the ticket or appeal to a particular constituency. The vice presidential candidate might also be chosen on the basis of traits the presidential candidate is perceived to lack, or on the basis of name recognition. To foster party unity, popular runners-up in the presidential nomination process are commonly considered.

The ultimate goal of vice presidential candidate selection is to help and not hurt the party's chances of getting elected. An overly dynamic selection can backfire by outshining the presidential candidate. A classic example of this came in 1988, when Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis chose experienced Texas Senator Lloyd Bentsen as his running mate. In two other cases the selection was seen to have hurt the nominee. In 1984 Walter Mondale picked Geraldine Ferraro whose nomination became a drag on the ticket due to repeated questions about her husband's finances. In 2008, John McCain picked as his running mate the governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin. This selection was seen to have hurt the ticket, as at the time she was not well known. [11]

The first presidential candidate to choose his vice presidential candidate was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1940.[12] The last not to name a vice presidential choice, leaving the matter up to the convention, was Democrat Adlai Stevenson in 1956. The convention chose Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver over Massachusetts Senator (and later president) John F. Kennedy. At the tumultuous 1972 Democratic convention, presidential nominee George McGovern selected Senator Thomas Eagleton as his running mate, but numerous other candidates were either nominated from the floor or received votes during the balloting. Eagleton nevertheless received a majority of the votes and the nomination.

In cases where the presidential nomination is still in doubt as the convention approaches, the campaigns for the two positions may become intertwined. In 1976, Ronald Reagan, who was trailing President Gerald R. Ford in the presidential delegate count, announced prior to the Republican National Convention that, if nominated, he would select Senator Richard Schweiker as his running mate. This move backfired to a degree, as Schweiker's relatively liberal voting record alienated many of the more conservative delegates who were considering a challenge to party delegate selection rules to improve Reagan's chances. In the end, Ford narrowly won the presidential nomination and Reagan's selection of Schweiker became moot.

Role of the Vice President

Duties

The Constitution limits the formal powers and role of Vice President to becoming President should the President become unable to serve (due to the death, resignation, or medical impairment of the President) and sometimes acting as the presiding officer of the U.S. Senate. As President of the Senate, the Vice President has two primary duties: to cast a vote in the event of a Senate deadlock and to preside over and certify the official vote count of the U.S. Electoral College. For example, in the first half of 2001, the Senators were divided 50-50 between Republicans and Democrats and Dick Cheney's tie-breaking vote gave the Republicans the Senate majority. (See 107th United States Congress.)

Except for this tie-breaking role, the Standing Rules of the Senate do not vest any significant responsibilities in the Vice President. Rule XIX, which governs debate, does not authorize the Vice President to participate in debate, and grants only to members of the Senate (and, upon appropriate notice, former presidents of the United States) the privilege of addressing the Senate, without granting a similar privilege to the sitting Vice President. Thus, as Time Magazine wrote during the controversial tenure of Vice-President Charles G. Dawes, "once in four years the Vice President can make a little speech, and then he is done. For four years he then has to sit in the seat of the silent, attending to speeches ponderous or otherwise, of deliberation or humor."[13]

The informal roles and functions of the Vice President depend on the specific relationship between the President and the Vice President, but often include drafter and spokesperson for the administration's policy, as an adviser to the president, as Chairman of the Board of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), as a Member of the board of the Smithsonian Institution, and as a symbol of American concern or support. The influence of the Vice President in this role depends almost entirely on the characteristics of the particular administration. Vice President Cheney, for instance, is widely regarded as one of President George W. Bush's closest confidants. Al Gore was an important advisor to President Bill Clinton on matters of foreign policy and the environment. Often, Vice Presidents will take harder-line stands on issues to ensure the support of the party's base while deflecting partisan criticism away from the President. Under the American system the President is both head of state and head of government, and the ceremonial duties of the former position are often delegated to the Vice President. The Vice President may meet with other heads of state or attend state funerals in other countries, at times when the administration wishes to demonstrate concern or support but cannot send the President himself. Not all Vice Presidents are happy in their jobs. John Nance Garner, who served as Vice President from 1933 to 1941 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, famously remarked that the Vice Presidency wasn't "worth a pitcher of warm piss,"[14] although reporters allegedly changed the last word to "spit" for print.

In recent years, the Vice Presidency has frequently been used to launch bids for the presidency. Of the thirteen presidential elections from 1956 to 2004, nine featured the incumbent president; the other four (1960, 1968, 1988, 2000) all featured the incumbent Vice President. Former Vice Presidents also ran, in 1984 (Walter Mondale), and in 1968 (Richard Nixon, against the incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey). The first presidential election to include neither the incumbent president nor the incumbent Vice President on a major party ticket since 1952 came in 2008 when President George W. Bush had already served two terms and Vice President Cheney chose not to run.

Since 1974, the official residence of the Vice President and his family has been Number One Observatory Circle, on the grounds of the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.

The Vice Presidential Service Badge is a U.S. military badge of the Department of Defense that is awarded to members of the U.S. military, personnel of the commissioned corps of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and personnel of the commissioned corps of the United States Public Health Service who serve as full-time uniformed service aides to the Vice President.

President of the Senate

As President of the Senate (Article I, Section 3), the Vice President oversees procedural matters and may cast a tie-breaking vote. There is a strong convention within the U.S. Senate that the Vice President not use their position as President of the Senate to influence the passage of legislation or act in a partisan manner, except in the case of breaking tie votes. As President of the Senate, John Adams cast twenty-nine tie-breaking votes—a record that no successor except for John C. Calhoun ever threatened. His votes protected the president's sole authority over the removal of appointees, influenced the location of the national capital, and prevented war with Great Britain. On at least one occasion he persuaded senators to vote against legislation that he opposed, and he frequently lectured the Senate on procedural and policy matters. Adams' political views and his active role in the Senate made him a natural target for critics of the Washington administration. Toward the end of his first term, as a result of a threatened resolution that would have silenced him except for procedural and policy matters, he began to exercise more restraint in the hope of realizing the goal shared by many of his successors: election in his own right as president of the United States of America.

In modern times, the Vice President rarely presides over day-to-day matters in the Senate; in his place, the Senate chooses a President pro tempore (or "president for a time") to preside in the Vice President's absence, and the Senate maintains a Duty Roster for the post, normally selecting the longest serving senator in the majority party.

When the President is impeached, the Chief Justice of the United States of America presides over the Senate during the impeachment trial. Otherwise, the Vice President, in the capacity as President of the Senate, or President pro tempore of the Senate presides. This may include the impeachment of the Vice President, although legal theories suggest the law would not allow a person to be the judge in a case where they were the defendant. If the Vice President did not preside over an impeachment, the duties would fall to the President Pro Tempore.

The President of the Senate also presides over counting and presentation of the votes of the U.S. Electoral College. This process occurs in the presence of both houses of Congress, on January 6 of the year following a U.S. presidential election. In this capacity, only four Vice Presidents have been able to announce their own election to the presidency: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Martin Van Buren, and George H. W. Bush. At the beginning of 1961, it fell to Richard Nixon to preside over this process, which officially announced the election of his 1960 opponent, John F. Kennedy. In 1969, Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced he had lost to Nixon. Later, in 2001, Al Gore announced the election of his opponent, George W. Bush.

Vice President John C. Calhoun became the first Vice President to resign the office. He had been dropped from the ticket by President Andrew Jackson in favor of Martin Van Buren. Already a lame-duck Vice President, he was elected to the Senate by the South Carolina state legislature and resigned the Vice Presidency early to begin his Senate term because he believed he would have more power as a senator.

Growth of the office

For much of its existence, the office of Vice President was seen as little more than a minor position. John Adams, the first Vice President, described it as "the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived." Thomas R. Marshall, the 28th Vice President, lamented: "Once there were two brothers. One ran away to sea; the other was elected Vice President of the United States. And nothing was heard of either of them again."[15] When the Whig Party was looking for a Vice President on Zachary Taylor's ticket, they approached Daniel Webster, who said of the offer, "I do not intend to be buried until I am dead." This was the second time Webster declined the office; both times, the President making the offer died in office. The natural stepping stone to the Presidency was long considered to be the office of Secretary of State.

For many years, the Vice President was given few responsibilities. After John Adams attended a meeting of the president's Cabinet in 1791, no Vice President did so again until Thomas Marshall stood in for President Woodrow Wilson while he traveled to Europe in 1918 and 1919. Marshall's successor, Calvin Coolidge, was invited to meetings by President Warren G. Harding. The next Vice President, Charles G. Dawes, did not seek to attend Cabinet meetings under President Coolidge, declaring that "the precedent might prove injurious to the country."[16] Vice President Charles Curtis was also precluded from attending by President Herbert Hoover.

Garret Hobart, the first Vice President under William McKinley, was one of the very few Vice Presidents at this time who played an important role in the administration. A close confidant and adviser of the President, Hobart was called Assistant President.[17]

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt raised the stature of the office by renewing the practice of inviting the Vice President to cabinet meetings, which has been maintained by every president since. Roosevelt's first Vice President, John Nance Garner, broke with him at the start of the second term on the Court-packing issue and became Roosevelt's leading political enemy. Garner's successor, Henry Wallace, was given major responsibilities during the war, but he moved further to the left than the Democratic Party and the rest of the Roosevelt administration and was relieved of actual power. Roosevelt kept his last Vice President, Harry Truman, uninformed on all war and postwar issues, such as the atomic bomb, leading Truman to wryly remark that the job of the Vice President is to "go to weddings and funerals." Following Roosevelt's death and Truman's ascension to the presidency, the need to keep Vice Presidents informed on national security issues became clear, and Congress made the Vice President one of four statutory members of the National Security Council in 1949.

Richard Nixon reinvented the office of Vice President. He had the attention of the media and the Republican party, when Dwight Eisenhower ordered him to preside at Cabinet meetings in his absence. Nixon was also the first Vice President to temporarily assume control of the executive branch, which he did after Eisenhower suffered a heart attack on September 24, 1955, ileitis in June 1956, and a stroke in November 1957. President Jimmy Carter was the first president to formally give his Vice President, Walter Mondale, an office in the West Wing of the White House.

Succession and the 25th Amendment

The U.S. Constitution provides that should the president die or become disabled while in office, the "powers and duties" of the office are transferred to the Vice President. Initially, it was unclear whether the Vice President actually became the new president or merely acting president. This was first tested in 1841 with the death of President William Henry Harrison. Harrison's Vice President, John Tyler, asserted that he had succeeded to the full presidential office, powers, and title, and declined to acknowledge documents referring to him as "Acting President." Despite some strong calls against it, Tyler took the oath of office, becoming the tenth president. Tyler's claim was not challenged legally, and so the precedent of full succession was established. This was made explicit by Section 1 of the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1967.

The 25th Amendment also made provisions for a replacement in the event that the Vice President died in office, resigned, or succeeded to the presidency. The original Constitution had no provision for selecting such a replacement, so the office of Vice President remained vacant until the beginning of the next presidential and vice presidential terms. This issue had arisen most recently with the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and was rectified by section 2 of the 25th Amendment.

Section 2 of the 25th Amendment provides that "Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress." Gerald Ford was the first Vice President selected by this method, after the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew in 1973; after succeeding to the Presidency, Ford nominated Nelson Rockefeller as Vice President.

Another issue was who had the power to declare that an incapacitated president is unable to discharge his duties. This question had arisen most recently with the illnesses of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Sections 3 and 4 of the amendment provide means for the Vice President to become Acting President upon the temporary disability of the president. Section 3 deals with self-declared incapacity of the president, and section 4 deals with incapacity declared by the joint action of the Vice President and of a majority of the Cabinet.

While section 4 has never been invoked, section 3 has been invoked three times: on July 13, 1985 when Ronald Reagan underwent surgery to remove cancerous polyps from his colon, and twice more on June 29, 2002 and July 21, 2007 when George W. Bush underwent colonoscopy procedures requiring sedation. Prior to this amendment, Vice President Richard Nixon informally replaced President Dwight Eisenhower for a period of weeks on each of three occasions when Eisenhower was ill.

Salary

The Vice President's salary is the same as that of the Chief Justice of the United States and the Speaker of the House of Representatives which for 2008 is set at $221,000.[18] The salary was set by the 1989 government salary reform act which also provides for an automatic cost of living adjustment for federal employees.

The Vice President does not automatically receive a pension based on that office, but instead receives the same pension as other members of Congress based their position as president of the Senate.[19] The Vice President must serve a minimum of five years to qualify for a pension.[20]

Vice Presidents of the United States

- See also: List of Vice Presidents of the United States

Prior to ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967, no provision existed for filling a vacancy in the office of Vice President. As a result, the Vice Presidency was left vacant 16 times, sometimes for nearly four years, until the next ensuing election and inauguration—eight times due to the death of the sitting president, resulting in the Vice President's becoming President; seven times due to the death of the sitting Vice President; and once due to the resignation of Vice President John C. Calhoun to become a senator. Since the adoption of the 25th Amendment, the office has been vacant twice while awaiting confirmation of the new Vice President by both houses of Congress.

The first such instance occurred in 1973 following the resignation of Spiro Agnew as Richard Nixon's vice president. Gerald Ford was subsequently appointed by Nixon and confirmed by Congress. The second occurred 10 months later when Nixon resigned following the Watergate scandal and Ford assumed the presidency. The resulting vice presidential vacancy was filled by Nelson Rockefeller. Ford and Rockefeller are the only two people to have served as Vice President without having been elected to the office.

Once the election is over, the Vice President's usefulness is over. He's like the second stage of a rocket. He's damn important going into orbit, but he's always thrown off to burn up in the atmosphere.

– An aide to Vice President Hubert Humphrey quoted by Light 1984 cited in Sigelman and Wahlbeck 1997[12]

Former Vice Presidents

As of 2008 four living former Vice Presidents are:

Bush was elected President, while Mondale and Gore were nominees of the Democratic party that failed to become president. Quayle briefly sought the Republican nomination.

Former Vice Presidents are entitled to lifetime pension, but unlike former Presidents they are not entitled to Secret Service personal protection.[21] However, former Vice Presidents unofficially receive Secret Service protection for up to six months after leaving office.[22]

As of June 2008, a bill entitled the "Former Vice President Protection Act of 2008" had passed in the House of Representatives.[23] Still needing Senate consideration, the bill would provide six-month Secret Service protection by law to a former Vice President and family.[24]

Former Democratic Vice Presidents are ex officio superdelegates to the Democratic National Convention.

Records

- Longevity

- John Nance Garner died fifteen days before his 99th birthday.

- Levi P. Morton died on his 96th birthday.

- Gerald Ford died at the age of 93.

- John Adams died at the age of 90.

- Age while in office

- John C. Breckinridge, the youngest ever to serve, was 36 when he became Vice President in 1857.

- Alben W. Barkley, the oldest ever to serve, was 75 when he left the vice presidency in 1953.

- Two served under two different Presidents

- George Clinton under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison

- John C. Calhoun under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson

- Seven died in office

- George Clinton in 1812

- Elbridge Gerry in 1814

- William R. King in 1853

- Henry Wilson in 1875

- Thomas Hendricks in 1885

- Garret Hobart in 1899

- James Sherman in 1912

- Two resigned

- John C. Calhoun resigned on December 28, 1832, to take a seat in the Senate, having been chosen to fill a vacancy.

- Spiro Agnew resigned on October 10, 1973, upon pleading no contest to charges of accepting bribes while governor of Maryland.

- Three were the apparent target of an assassination attempt (all three unsuccessful)

- Andrew Johnson was a target of the same conspiracy which murdered President Abraham Lincoln and attempted to murder Secretary of State William H. Seward

- Thomas R. Marshall was a target of a letter bomb in 1915

- Dick Cheney was in the vicinity of a bomb allegedly meant for him. See 2007 Bagram Air Base bombing.

- Two were never elected to the office

- Gerald Ford was nominated to office upon the resignation of Spiro Agnew in 1973. Following Richard Nixon's resignation, he became the first, and so far the only, person to become the President without having been elected to national executive office.

- Nelson Rockefeller was nominated to office upon the succession of Gerald Ford to the Presidency in 1974.

- Nine succeeded to the Presidency

- John Tyler became President when William Henry Harrison died. Initially sought re-election in 1844 as the nominee of the "National Democratic Tyler Convention" but withdrew before the election.

- Millard Fillmore became President when Zachary Taylor died. Sought the Whig nomination in 1852, but lost to Winfield Scott. Four years later, ran and lost as the candidate of the American and Whig Parties.

- Andrew Johnson became President when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Sought the Democratic nomination in 1868, but was unsuccessful.

- Chester A. Arthur became President when James Garfield was assassinated. Sought a full term, but was not re-nominated.

- Theodore Roosevelt became President when William McKinley was assassinated; then was elected to full term. Did not seek re-election. Four years after leaving office, ran again and lost.

- Calvin Coolidge became President when Warren Harding died; then was elected to full term. Did not seek re-election.

- Harry S. Truman became President when Franklin D. Roosevelt died; then was elected to full term. Did not seek re-election.

- Lyndon B. Johnson became President when John F. Kennedy was assassinated; then was elected to full term. Did not seek re-election.

- Gerald Ford became President when Richard Nixon resigned; then lost election to full term.

- Four sitting Vice Presidents were elected President

- John Adams (1789–1797) was elected President in 1796.

- Thomas Jefferson (1797–1801) was elected President in 1800.

- Martin Van Buren (1833–1837) was elected President in 1836.

- George H. W. Bush (1981–1989) was elected President in 1988.

- One non-sitting former Vice President was elected President

- Richard Nixon was elected President in 1968. He had been Vice President to Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1961.

Nixon is the only person to be elected as Vice President for two terms and President for two terms. Since Franklin D. Roosevelt died shortly into his fourth term, it is Nixon who held nationally elected office for the longest duration, out-serving Roosevelt by a little more than a year and five months, although not consecutively.

- Only one president (Franklin D. Roosevelt) had more than two different Vice Presidents

- Two have been Acting President

- George H. W. Bush acted as President for Ronald Reagan on July 13, 1985.

- Dick Cheney has acted twice as President for George W. Bush, on June 29, 2002 and July 21, 2007[25].

They officially acted as President due to presidential incapacity under the 25th Amendment.

- Two have been indicted for treason after leaving office

- Aaron Burr who was acquitted

- John C. Breckinridge, an exiled Confederate General was never actually tried

- Vice Presidents who became Nobel Peace Prize Laureates

- Theodore Roosevelt 1906 (when he was the President)

- Charles Gates Dawes 1925

- Al Gore 2007 (after he left the office)

- Seven served two full terms

- John Adams

- Daniel Tompkins

- Thomas R. Marshall

- John Garner

- Richard Nixon

- George H. W. Bush

- Al Gore

- Previous positions

As of 2008[update] every Vice President except John Adams, Chester A. Arthur, Henry A. Wallace, Charles Dawes and Garret Hobart has served as a congressman, senator, or governor.

- One Vice President wrote a #1 hit song

- Charles Dawes co-wrote "It's All in the Game", a recording of which by Tommy Edwards hit Number One in 1957.

Notes and references

- ↑ "Vice President" may also be written "Vice-President", "Vice president" or "Vice-president". Because the modern usage is "Vice President", it has been used here for consistency.

- ↑ "U.S. Const., art. I, § 3".

- ↑ Goldstein, Joel K. (1995). "The New Constitutional Vice Presidency". Wake Forest Law Review (Winston Salem, NC: Wake Forest Law Review Association, Inc.) 30 (505).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "U.S. Const., amd. XII".

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 See: U.S. Const. art. II, §1, cl. 5; see also, U.S. Const. amend. XII, §4.

- ↑ See: Peabody, Bruce G.; Gant, Scott E. (1999). "The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment". Minnesota Law Review (Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Law Review) 83 (565).

- ↑ See: Albert, Richard (2005). "The Evolving Vice Presidency". Temple Law Review (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education) 78 (811, at 856-9).

- ↑ See: ; see also: Standing Rules of the Senate: Rule III

- ↑ Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996. Official website of the National Archives. (July 30, 2005).

- ↑ Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996. Official website of the National Archives. (July 30, 2005).

- ↑ U.S. National Archives Web Site, Electoral College

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 http://www.jstor.org/pss/2952169

- ↑ "President Dawes," Time Magazine, 1924-12-14.

- ↑ "John Nance Garner quotes". Retrieved on 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "A heartbeat away from the presidency: vice presidential trivia". Case Western Reserve University (2004-10-04). Retrieved on 2008-09-12.

- ↑ U.S. Senate Web page on Charles G. Dawes, 30th Vice President (1925-1929)

- ↑ "Garret Hobart<!- Bot generated title ->". Retrieved on 2008-08-25.

- ↑ Current salary information from About.com [1]

- ↑ CRS Report for Congress-Reitrement Benefits for Members of Congress[2]

- ↑ Pension information from Slate.com[3]

- ↑ "Internet Public Library: FARQs<!- Bot generated title ->". Retrieved on 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "CNN.com<!- Bot generated title ->". Retrieved on 2008-08-25.

- ↑ Former Vice President Protection Act of 2008

- ↑ House bill would extend protections to ex-vice presidents

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/6909160.stm

Further reading

- Tally, Steve (1992). Bland Ambition: From Adams to Quayle—The Cranks, Criminals, Tax Cheats, and Golfers Who Made It to Vice President. Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-613140-4.

External links

- White House website for the Vice President

- Vice Presidents.com

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825

- Amendment25.com

- AboutGovernmentStates.com

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||