Vector field

In mathematics a vector field is a construction in vector calculus which associates a vector to every point in a (locally) Euclidean space.

Vector fields are often used in physics to model, for example, the speed and direction of a moving fluid throughout space, or the strength and direction of some force, such as the magnetic or gravitational force, as it changes from point to point.

In the rigorous mathematical treatment, (tangent) vector fields are defined on manifolds as sections of a manifold's tangent bundle. They are one kind of tensor field on the manifold.

Contents |

Definition

Vector fields on subsets of Euclidean space

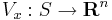

Given a subset S in Rn, a vector field is represented by a vector-valued function  in standard Euclidean coordinates (x1, ..., xn). If there is another coordinate system y on S, then

in standard Euclidean coordinates (x1, ..., xn). If there is another coordinate system y on S, then  is the expression for the same vector field in the new coordinates y. In particular, a vector field is not just a collection of scalar fields.

is the expression for the same vector field in the new coordinates y. In particular, a vector field is not just a collection of scalar fields.

We say V is a Ck vector field if V is k times continuously differentiable. A point p in S is called stationary if the vector at that point is zero ( ).

).

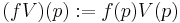

A vector field can be visualized as an n-dimensional space with an n-dimensional vector attached to each point. Given two Ck-vector fields V, W defined on S and a real valued Ck-function f defined on S, the two operations scalar multiplication and vector addition

define the module of Ck-vector fields over the ring of Ck-functions.

Vector fields on manifolds

Given a manifold M, a vector field on M is a continuous assignment to every point of M a tangent vector to M at that point. That is, for each x in M, we have a tangent vector v(x) in TxM such that the map sending a point to the appropriate tangent vector is a continuous function from the manifold to the total space of its tangent bundle. More precisely, a vector field is a section of the tangent bundle TM. If this section is continuous/differentiable/smooth/analytic, then we call the vector field continuous/differentiable/smooth/analytic. It is important to note that these properties are invariant under the change of coordinates formula, and thus can be detected by computing the local representation in any continuous/differentiable/smooth/analytic chart.

The collection of all vector fields on M is often denoted by Γ(TM) or C∞(M,TM) (especially when thinking of vector fields as sections); the collection of all smooth vector fields is sometimes also denoted by  (a fraktur "X").

(a fraktur "X").

Notes

Vector fields should be contrasted with scalar fields, which associate a number or scalar to every point in space (or every point of some manifold). Vector fields similarly associate a length or magnitude, as well as a direction to every point in space. For example, in the common (x,y,z) three-space, every point in the manifold can be associated parametrically with magnitudes of x, y and z components.

The divergence and curl are two operations on a vector field which result in a scalar field and another vector field respectively. The first of these operations is defined in any number of dimensions (that is, for any value of n). The curl however, is defined only for n=3, but it can be generalized to an arbitrary dimension using the exterior product and exterior derivative.

Examples

- A vector field for the movement of air on Earth will associate for every point on the surface of the Earth a vector with the wind speed and direction for that point. This can be drawn using arrows to represent the wind; the length (magnitude) of the arrow will be an indication of the wind speed. A "high" on the usual barometric pressure map would then act as a source (arrows pointing away), and a "low" would be a sink (arrows pointing towards), since air tends to move from high pressure areas to low pressure areas.

- Velocity field of a moving fluid. In this case, a velocity vector is associated to each point in the fluid.

- Streamlines, Streaklines and Pathlines are 3 types of lines that can be made from vector fields. They are :

-

- streaklines — as revealed in wind tunnels using smoke.

- streamlines (or fieldlines)— as a line depicting the instantaneous field at a given time.

- pathlines — showing the path that a given particle (of zero mass) would follow.

- Magnetic fields. The fieldlines can be revealed using small iron filings.

- Maxwell's equations allow us to use a given set of initial conditions to deduce, for every point in Euclidean space, a magnitude and direction for the force experienced by a charged test particle at that point; the resulting vector field is the electromagnetic field.

- A gravitational field generated by any massive object is also a vector field. For example, the gravitational field vectors for a spherically symmetric body would all point towards the sphere's center with the magnitude of the vectors reducing as radial distance from the body increases.

Gradient field

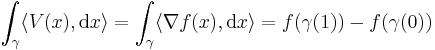

Vector fields can be constructed out of scalar fields using the vector operator gradient which gives rise to the following definition.

A vector field V defined on a set S is called a gradient field or a conservative field if there exists a real valued function (a scalar field) f on S such that

.

.

The associated flow is called the gradient flow, and is used in the method of gradient descent.

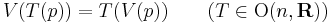

The path integral along any closed curve γ (γ(0) = γ(1)) in a gradient field is zero:

.

.

Central field

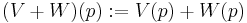

A C∞-vector field over Rn \ {0} is called a central field if

where O(n, R) is the orthogonal group. We say central fields are invariant under orthogonal transformations around 0.

The point 0 is called the center of the field.

Since orthogonal transformations are actually rotations and reflections, the invariance conditions mean that vectors of a central field are always directed towards, or away from, 0; this is an alternate (and simpler) definition. A central field is always a gradient field, since defining it on one semiaxis and integrating gives an antigradient.

Line integral

A common technique in physics is to integrate a vector field along a curve: a line integral. Given a particle in a gravitational vector field, where each vector represents the force acting on the particle at this point in space, the line integral is the work done on the particle when it travels along a certain path.

The line integral is constructed analogously to the Riemann integral and it exists if the curve is rectifiable (has finite length) and the vector field is continuous.

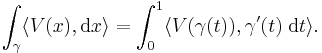

Given a vector field V and a curve γ parametrized by [0, 1] the line integral is defined as

Flow curves

Vector fields have a nice interpretation in terms of autonomous, first order ordinary differential equations.

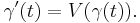

Given a vector field V defined on S, we can try to define curves γ on S such that for each t in an interval I

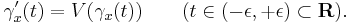

If V is Lipschitz continuous we can find a unique C1-curve γx for each point x in S so that

The curves γx are called flow curves of the vector field V and partition S into equivalence classes. It is not always possible to extend the interval (-ε, +ε) to the whole real number line. The flow may for example reach the edge of S in a finite time. In two or three dimensions one can visualize the vector field as giving rise to a flow on S. If we drop a particle into this flow at a point p it will move along the curve γp in the flow depending on the initial point p. If p is a stationary point of V then the particle will remain at p.

Typical applications are streamline in fluid, geodesic flow, and one-parameter subgroups and the exponential map in Lie groups.

Complete vector fields

A vector field is complete if its flow curve exists for all time.[1] In particular, compactly supported vector fields on a manifold are complete. If X is a complete vector field on M, then the one-parameter group of diffeomorphisms generated by the flow along X exists for all time.

Difference between scalar and vector field

The difference between a scalar and vector field is not that a scalar is just one number while a vector is several numbers. The difference is in how their coordinates respond to coordinate transformations. A scalar is a coordinate whereas a vector can be described by coordinates, but it is not the collection of its coordinates.

Example 1

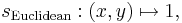

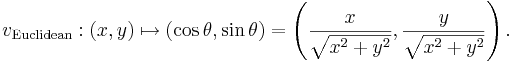

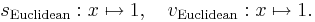

This example is about 2-dimensional Euclidean space (R2) where we examine Euclidean (x, y) and polar (r, θ) coordinates (which are undefined at the origin). Thus x = r cos θ and y = r sin θ and also r2 = x2 + y2, cos θ = x/(x2 + y2)1/2 and sin θ = y/(x2 + y2)1/2. Suppose we have a scalar field which is given by the constant function 1, and a vector field which attaches a vector in the r-direction with length 1 to each point. More precisely, they are given by the functions

Let us convert these fields to Euclidean coordinates. The vector of length 1 in the r-direction has the x coordinate cos θ and the y coordinate sin θ. Thus in Euclidean coordinates the same fields are described by the functions

We see that while the scalar field remains the same, the vector field now looks different. The same holds even in the 1-dimensional case, as illustrated by the next example.

Example 2

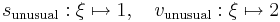

Consider the 1-dimensional Euclidean space R with its standard Euclidean coordinate x. Suppose we have a scalar field and a vector field which are both given in the x coordinate by the constant function 1,

Thus, we have a scalar field which has the value 1 everywhere and a vector field which attaches a vector in the x-direction with magnitude 1 unit of x to each point.

Now consider the coordinate ξ := 2x. If x changes one unit then ξ changes 2 units. Thus this vector field has a magnitude of 2 in units of ξ. Therefore, in the ξ coordinate the scalar field and the vector field are described by the functions

which are different.

See also

- Field line

- Lie derivative

- Time-dependent vector field

- Vector fields in cylindrical and spherical coordinates

- Scalar field

- Tensor field

References

- ↑ Sharpe, R. (1997). Differential geometry. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94732-9.

External links

- Vector field -- Mathworld

- Vector field -- PlanetMath

- 3D Magnetic field viewer

- Vector Field Simulation Java applet illustrating vectors fields

- Vector fields and field lines

- Vector field simulation An interactive application to show the effects of vector fields