Array

| Linear data structures |

|---|

|

Array |

In computer science an array[1] is a data structure consisting of a group of elements that are accessed by indexing. In most programming languages each element has the same data type and the array occupies a contiguous area of storage.

Contents |

Overview

Most programming languages have a built-in array data type, although what is called an array in the language documentation is sometimes really an associative array. Conversely, the contiguous storage kind of array discussed here may alternatively be called a vector, list,[2] or table.[3]

Some programming languages support array programming (e.g., APL, newer versions of Fortran) which generalises operations and functions to work transparently over arrays as they do with scalars, instead of requiring looping over array members.

Multi-dimensional arrays are accessed using more than one index: one for each dimension. Multidimensional indexing reduced to a lesser number of dimensions, for example, a two-dimensional array with consisting of 6 and 5 elements respectively could be represented using a one-dimensional array of 30 elements.

Arrays can be classified as fixed-sized arrays (sometimes known as static arrays) whose size cannot change once their storage has been allocated, or dynamic arrays, which can be resized.

Properties

Arrays permit constant time (O(1)) random access to individual elements, which is optimal, but moving elements requires time proportional to the number of elements moved. On actual hardware, the presence of e.g. caches can make sequential iteration over an array noticeably faster than random access — a consequence of arrays having good locality of reference because their elements occupy contiguous memory locations — but this does not change the asymptotic complexity of access. Likewise, there are often facilities (such as memcpy) which can be used to move contiguous blocks of array elements faster than one can do through individual element access, but that does not change the asymptotic complexity either.

Memory-wise, arrays are compact data structures with no per-element overhead. There may be a per-array overhead, e.g. to store index bounds, but this is language-dependent. It can also happen that elements stored in an array require less memory than the same elements stored in individual variables, because several array elements can be stored in a single word; such arrays are often called packed arrays.

Properties in comparison

Dynamic arrays have similar characteristics to arrays, but can grow. The price for this is a memory overhead, due to elements being allocated but not used. With a constant per-element bound on the memory overhead, dynamic arrays can grow in constant amortized time per element.

Associative arrays provide a mechanism for array-like functionality without huge storage overheads when the index values are sparse. Specialized associative arrays with integer keys include Patricia tries and Judy arrays.

Balanced trees require O(log n) time for index access, but also permit inserting or deleting elements in Θ(log n) time.[4] Arrays require O(n) time for insertion and deletion of elements.

Applications

Arrays are used to implement mathematical vectors and matrices, as well as other kinds of rectangular tables. In early programming languages, these were often the applications that motivated having arrays.

Because of their performance characteristics, arrays are used to implement other data structures, such as heaps, hash tables, deques, queues, stacks, strings, and VLists.

One or more large arrays are sometimes used to emulate in-program dynamic memory allocation, particularly memory pool allocation. Historically, this has sometimes been the only way to allocate "dynamic memory" portably.

Array accesses with statically predictable access patterns are a major source of data parallelism.

Some algorithms store a variable number of elements in part of a fixed-size array, which is equivalent to using dynamic array with a fixed capacity; the so-called Pascal strings are examples of this.

Indexing

The valid index values of each dimension of an array are a bounded set of integers (or values of some enumerated type). Programming environments that check indexes for validity are said to perform bounds checking.

Index of the first element

The index of the first element (sometimes called the "origin") varies by language. There are three main implementations: zero-based, one-based, and n-based arrays, for which the first element has an index of zero, one, or a programmer-specified value. The zero-based array is more natural in the root machine language and was popularized by the C programming language, in which the abstraction of array is very weak, and an index n of a one-dimensional array is simply the offset of the element accessed from the address of the first (or "zeroth") element (scaled by the size of the element). One-based arrays are based on traditional mathematics notation for matrices and most, but not all, mathematical sequences. n-based is made available so the programmer is free to choose the lower bound, which may even be negative, which is most naturally suited for the problem at hand.

The Comparison of programming languages (array), indicates the base index used by various languages.

Supporters of zero-based indexing sometimes criticize one-based and n-based arrays for being slower. Often this criticism is mistaken when one-based or n-based array accesses are optimized with common subexpression elimination (for single dimensioned arrays) and/or with well-defined dope vectors (for multi-dimensioned arrays). However, in multidimensional arrays where the net offset into linear memory is computed from all of the indices, zero-based indexing is more natural, simpler, and faster. Edsger W. Dijkstra expressed an opinion in this debate: Why numbering should start at zero.

The 0-based/1-based debate is not limited to just programming languages. For example, the ground-floor of a building is elevator button "0" in France, but elevator button "1" in the USA.

Index of the last element

The relation between numbers appearing in an array declaration and the index of that array's last element also varies by language. In some languages (e.g. C) the number of elements contained in the arrays must be specified, whereas in others (e.g. Visual Basic .NET) the numeric value of the index of the last element must be specified.

Indexing methods

When an array is implemented as continuous storage, the index-based access, e.g. to element n, is simply done (for zero-based indexing) by using the address of the first element and adding n · sizeof(one element). So this is a Θ(1) operation.

Multi-dimensional arrays

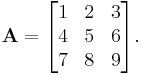

Ordinary arrays are indexed by a single integer. Also useful, particularly in numerical and graphics applications, is the concept of a multi-dimensional array, in which we index into the array using an ordered list of integers, such as in a[3,1,5]. The number of integers in the list used to index into the multi-dimensional array is always the same and is referred to as the array's dimensionality, and the bounds on each of these are called the array's dimensions. An array with dimensionality k is often called k-dimensional. One-dimensional arrays correspond to the simple arrays discussed thus far; two-dimensional arrays are a particularly common representation for matrices. In practice, the dimensionality of an array rarely exceeds three. Mapping a one-dimensional array into memory is obvious, since memory is logically itself a (very large) one-dimensional array. When we reach higher-dimensional arrays, however, the problem is no longer obvious. Suppose we want to represent this simple two-dimensional array:

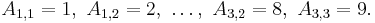

It is most common to index this array using the RC-convention, where elements are referred in row, column fashion or  , such as:

, such as:

Common ways to index into multi-dimensional arrays include:

- Row-major order. Used most notably by statically-declared arrays in C. The elements of each row are stored in order.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

- Column-major order. Used most notably in Fortran. The elements of each column are stored in order.

| 1 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

- Arrays of arrays. Multi-dimensional arrays are typically represented by one-dimensional arrays of references (Iliffe vectors) to other one-dimensional arrays. The subarrays can be either the rows or columns.

The first two forms are more compact and have potentially better locality of reference, but are also more limiting; the arrays must be rectangular, meaning that no row can contain more elements than any other. Arrays of arrays, on the other hand, allow the creation of ragged arrays, also called jagged arrays, in which the valid range of one index depends on the value of another, or in this case, simply that different rows can be different sizes. Arrays of arrays are also of value in programming languages that only supply one-dimensional arrays as primitives.

In many applications, such as numerical applications working with matrices, we iterate over rectangular two-dimensional arrays in predictable ways. For example, computing an element of the matrix product AB involves iterating over a row of A and a column of B simultaneously. In mapping the individual array indexes into memory, we wish to exploit locality of reference as much as we can. A compiler can sometimes automatically choose the layout for an array so that sequentially accessed elements are stored sequentially in memory; in our example, it might choose row-major order for A, and column-major order for B. Even more exotic orderings can be used, for example if we iterate over the main diagonal of a matrix.

See also

- Array slicing

- Collection class

- Comparison of programming languages (array)

- Parallel array

- Set (computer science)

- Sparse array

- Variable-length array

- wikibooks:Data Structures/Arrays

- wikibooks:Ada Programming/Types/array

References

- ↑ Paul E. Black, "array", in Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures, Paul E. Black, ed., U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 26 August 2008 (accessed 10 September 2008). [1]

- ↑ Tcl 8 lists are implemented using C vectors.

- ↑ This was the practice in some older languages, e.g. COBOL: Using Tables in COBOL

- ↑ Counted B-Tree