Evaporation

Evaporation, a type of phase transition, is the slow vaporization of a liquid, which is the opposite of condensation. It is the reaction by which molecules in a liquid state (e.g. water) spontaneously become gaseous (e.g. water vapor). Generally, evaporation can be seen by the gradual disappearance of a liquid when exposed to a significant volume of gas.

On average, the molecules do not have enough heat energy to escape from the liquid, or else the liquid would turn into vapor quickly. When the molecules collide, they transfer energy to each other in varying degrees, based on how they collide. Sometimes the transfer is so one-sided for a molecule near the surface that it ends up with enough energy to escape.

Liquids that do not evaporate visibly at a given temperature in a given gas (e.g. cooking oil at room temperature) have molecules that do not tend to transfer energy to each other in a pattern sufficient to frequently give a molecule the heat energy necessary to turn into vapor. However, these liquids are evaporating, it's just that the process is much slower and thus significantly less visible.

Evaporation is an essential part of the water cycle. Solar energy drives evaporation of water from oceans, lakes, moisture in the soil, and other sources of water. In hydrology, evaporation and transpiration (which involves evaporation within plant stomata) are collectively termed evapotranspiration. Evaporation is caused when water is exposed to air and the liquid molecules turn into water vapor which rises up and forms clouds.

Contents |

Theory

- See also: Kinetic theory

For molecules of a liquid to evaporate, they must be located near the surface, be moving in the proper direction, and have sufficient kinetic energy to overcome liquid-phase intermolecular forces.[1] Only a small proportion of the molecules meet these criteria, so the rate of evaporation is limited. Since the kinetic energy of a molecule is proportional to its temperature, evaporation proceeds more quickly at higher temperature. As the faster-moving molecules escape, the remaining molecules have lower average kinetic energy, and the temperature of the liquid thus decreases. This phenomenon is also called evaporative cooling. This is why evaporating sweat cools the human body. Evaporation also tends to proceed more quickly with higher flow rates between the gaseous and liquid phase and in liquids with higher vapor pressure. For example, laundry on a clothes line will dry (by evaporation) more rapidly on a windy day than on a still day.Three key parts to evaporation are heat, humidity and air movement.

On a molecular level, there is no strict boundary between the liquid state and the vapor state. Instead, there is a Knudsen layer, where the phase is undetermined. Because this layer is only a few molecules thick, at a macroscopic scale a clear phase transition interface can be seen.

Evaporative equilibrium

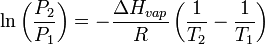

If evaporation takes place in a closed vessel, the escaping molecules accumulate as a vapor above the liquid. Many of the molecules return to the liquid, with returning molecules becoming more frequent as the density and pressure of the vapor increases. When the process of escape and return reaches an equilibrium,[1] the vapor is said to be "saturated," and no further change in either vapor pressure and density or liquid temperature will occur. For a system consisting of vapor and liquid of a pure substance, this equilibrium state is directly related to the vapor pressure of the substance, as given by the Clausius-Clapeyron relation:

where P1, P2 are the vapor pressures at temperatures T1, T2 respectively, ΔHvap is the enthalpy of vaporization, and R is the universal gas constant. The rate of evaporation in an open system is related to the vapor pressure found in a closed system. If a liquid is heated, when the vapor pressure reaches the ambient pressure the liquid will boil.

The ability for a molecule of a liquid to evaporate is largely based on the amount of kinetic energy an individual particle may possess. Even at lower temperatures, individual molecules of a liquid can evaporate if they have more than the minimum amount of kinetic energy required for vaporization.

Factors influencing the rate of evaporation

- Concentration of the substance evaporating in the air: If the air already has a high concentration of the substance evaporating, then the given substance will evaporate more slowly.

- Concentration of other substances in the air: If the air is already saturated with other substances, it can have a lower capacity for the substance evaporating.

- Flow rate of air: This is in part related to the concentration points above. If fresh air is moving over the substance all the time, then the concentration of the substance in the air is less likely to go up with time, thus encouraging faster evaporation. This is result of the boundary layer at the evaporation surface decreasing with flow velocity, decreasing the diffusion distance in the stagnant layer.

- Concentration of other substances in the liquid (impurities): If the liquid contains other substances, it will have a lower capacity for evaporation.

- Temperature of the substance: If the substance is hotter, then evaporation will be faster.

- Inter-molecular forces: The stronger the forces keeping the molecules together in the liquid state, the more energy one must get to escape.

- Surface area: A substance which has a larger surface area will evaporate faster as there are more surface molecules which are able to escape.

- Pressure: In an area of less pressure, evaporation happens faster because there is less exertion on the surface keeping the molecules from launching themselves.

In the US, the National Weather Service measures the actual rate of evaporation from a standardized "pan" open water surface outdoors, at various locations nationwide. Others do likewise around the world. The US data is collected and compiled into an annual evaporation map.[2] The measurements range from under 30 to over 120 inches per year.

Applications

When clothes are hung on a laundry line, even though the ambient temperature is below the boiling point of water, water evaporates. This is accelerated by factors such as low humidity, heat (from the sun), and wind. In a clothes dryer hot air is blown through the clothes, allowing water to evaporate very rapidly.

Combustion vaporization

Fuel droplets vaporize as they receive heat by mixing with the hot gases in the combustion chamber. Heat (energy) can also be received by radiation from any hot refractory wall of the combustion chamber.

Film deposition

Thin films may be deposited by evaporating a substance and condensing it onto a substrate.

See also

- Atmometer (evaporimeter)

- Crystallisation

- Desalination

- Distillation

- Drying

- Evaporator

- Evapotranspiration

- Flash evaporation

- Heat of vaporization

- Latent heat

- Pan evaporation

References

- Sze, Simon Min. Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology. ISBN 0-471-33372-7. Has an especially detailed discussion of film deposition by evaporation.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Silberberg, Martin A. (2006). Chemistry (4th edition ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 431–434. ISBN 0-07-296439-1.

- ↑ Geotechnical, Rock and Water Resources Library - Grow Resource - Evaporation

External links

-

From To Solid Liquid Gas Plasma Solid Solid-Solid Transformation Melting Sublimation - Liquid Freezing N/A Boiling/Evaporation - Gas Deposition Condensation N/A Ionization Plasma - - Recombination/Deionization N/A