Utrecht (city)

| Utrecht | |||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | |||

| Government | |||

| - mayor | Aleid Wolfsen | ||

| Area (2006) | |||

| - Total | 99.32 km² (38.3 sq mi) | ||

| - Land | 95.67 km² (36.9 sq mi) | ||

| - Water | 3.64 km² (1.4 sq mi) | ||

| Population (1 february, 2008) | |||

| - Total | 295.122 | ||

| - Density | 3,018/km² (7,816.6/sq mi) | ||

| Source: CBS, Statline. | |||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

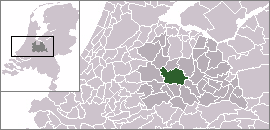

Utrecht () city and municipality is the capital and most populous city of the Dutch province of Utrecht. It is located in the North-Eastern end of the Randstad, and is the fourth largest city of the Netherlands, with a population of 296,305.[1] The smaller Utrecht agglomeration including adjacent suburbs and annexated towns is home to some 640,000 registered inhabitants, while the larger region contains up to 820,000 inhabitants.[2]

Utrecht's ancient city-centre features many buildings and structures from its earliest origins onwards. It has been the religious centre of the Netherlands since the eighth century CE. Currently it is the see of the Archbishop of Utrecht, the most important Dutch Roman Catholic leader.[3][4] Utrecht is also the see of an archbishop of the Old Catholic church, and the location of the offices of the main protestant church. Up till the golden age Utrecht was the city of most importance in the northern Netherlands (the present-day country of the Netherlands, excluding Belgium and Luxembourg), until Amsterdam became the cultural and populous centre of the Netherlands.

Utrecht is host to Utrecht University, the largest university of the Netherlands, as well as several other institutes for higher education. Due to its central position within the country it is an important transportation hub (rail and road) in the Netherlands. It has the second highest number of cultural events in the Netherlands, after Amsterdam.[5]

Contents |

History

Origins ( -650)

Although there is some evidence of earlier inhabitation in the region of Utrecht, dating back to the Stone age (app. 2200 BCE) and settling in the Bronze age (app. 1800-800 BCE)[6], the founding date of the city is usually related to the construction of a Roman fortification (castellum), probably built in around 50 CE. These fortresses were designed to house a cohort of about 500 Roman soldiers. Near the fort a settlement would grow housing artisans, traders and soldiers' wives and children. A line of such fortresses was built after the Roman emperor Claudius decided the empire should not expand further North. To consolidate the border the limes Germanicus defense line was constructed.[7] This line was located at the borders of the main branch of the river Rhine, which at that time flowed through a more northern bed compared to today. The name of the Utrecht fortress originally was simply Traiectum denoting its location on the Rhine at a ford. Later the name was adorned with the prefix Ultra (on the far side) to distinguish it from other settlements (for example Mosa Trajectum Maastricht). Over time the two parts of the name would merge and evolve into the current name (Utrecht).[8] In the second century, the wooden walls were replaced by sturdier tuff stone walls,[7] remnants of which are still to be found below the buildings around Dom Square.

From the middle of the 3rd century Germanic tribes regularly invaded the Roman territories. Around 275 the Romans could no longer maintain the northern border and Utrecht was abandoned.[7] Little is known about the next period 270-650. Utrecht is first spoken of again in the 7th century when the influence of the growing realms of the Franks lead Dagobert I to build a church devoted to Saint Martin within the walls of the Roman fortress[7]. In ongoing border conflicts with the Frisians the church was however destroyed.

Centre of Christianity in the Netherlands (650-1579)

By the mid of the 7th century, English and Irish missionaries set out to convert the Frisian. The pope appointed their leader, Willibrordus, archbishop of the Frisians; which is usually considered to initiation of archbishopric of Utrecht.[7] In 723, the Frankish king bestowed the fortress in Utrecht and the surrounding lands as the base of bishops. From then on Utrecht became one of the most influential seats of power for the Roman catholic church in the Netherlands. The see of the archbishops of Utrecht was located at the uneasy northern border of the Carolingian empire. Furthermore it had to compete with the nearby trading centre Dorestad, also founded near the location of a Roman fortress.[7] The political turmoil in the Frankish realms after the death of Charlemagne, in combination with viking raids and domination lead to the downfall of Dorestad and established Utrecht as one of the most important cities in the Netherlands.[9] The importance of Utrecht as a centre of Christianity is illustrated by the appointment of the Utrecht born Adriaan Florenszoon Boeyens to pope in 1522 (the last non Italian pope before John Paul II).

Prince-Bishops

When the Frankish rulers established the system of feudalism, the bishops of Utrecht came to exercise worldly power as prince-bishops.[7] The realm of the bishopry included not only land the modern province of Utrecht (Nedersticht, 'lower Sticht') but extended to the northeast. However, the feudalist system resulted in conflict between the different lords. The prince bishopry had its conflicts with the count of Holland and the dukes of Guelders.[10] The Veluwe was soon taken by Guelders, but large areas in the modern province of Overijssel remained as the Oversticht.

Clerical buildings

The clergy built several churches and monasteries inside, or close to the city of Utrecht. Most dominant of these was the gothic Cathedral of Saint Martin, inside the old Roman fortress. The construction of this cathedral started in 1254 after an earlier romanesque cathedral had been badly damaged by fire. When the choir and transept were finished from 1320 the ambitious Dom tower was built.[7] The central nave was the last part to be constructed from 1420. By that time, however, the time of the great cathedrals had and ended and the declining finances prevented this ambitious cathedral from being finished, resulting in the construction of the central nave being suspended before finishing the planned flying buttresses.[7] Besides the cathedral there were four additional collegiate churches in Utrecht: Saint Saviour (demolished in the 16th century), on the Dom square, dating back to the early 8th century.[11]; Saint John (Janskerk), originating in 1040;[12] Saint Peter, building started in 1039 [13] and Saint Mary's church building started around 1090 (demolished in the early 19th century, cloister survives).[14] Besides these churches the city housed Saint Paul abbey [15]. The 15th century beguine monastery of Saint Nicholas, and a 14th century chapter house of the Teutonic Knights.[16]

Besides these buildings which were part of the hierarchy of the bishopric; an additional four parish churches were constructed in the city: the Jacobichurch (dedicated to Saint James), founded in the 11th century, with the current gothic church dating back to the 14th century [17]; the Buurkerk (Neighbourhood-church) of the 11th century parish in the centre of the city; Nicolaichurch (dedicated to Saint Nicholas), from the 12th century [18] and the 13th century Geertekerk (dedicated to Saint Gertrude of Nivelles) [19]

City of Utrecht

The location on the banks of the river Rhine allowed Utrecht to become an important trade centre in the Northern Netherlands. The growing town Utrecht received city rights in 1122. When the main flow of the Rhine moved south, the old bed, which still flowed through the heart of the town became evermore canalized; and a unique wharf system was built as an inner city harbour system.[20] On the wharfs storage facilities (werfkelders) were built, on top of which the main street, including houses was constructed. The wharfs and the cellars are accessible from a platform at water level with stairs descending from the street level to form a unique structure.[nb 1][21]. The relations between the bishop, who controlled many lands outside of the city, and the citizens of Utrecht was not always easy.[7] The bishop, for example dammed the Lek at Wijk bij Duurstede to protect his estates from flooding. This threatened shipping for the city and lead to the city of Utrecht commissioning a canal, the Vaartse Rijn, to connect Utrecht to the Lek at Nieuwegein; to insure access to the town for shipping trade.

The end of independence

In 1528 the wordly powers of the bishop over both Neder- and Oversticht; including the city of Utrecht, were transferred to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who became the Lord of the 17 Netherlands (the current Benelux and the Northern parts of France). This transition was not an easy one and Charles V wanted to exert his power of the citizens of the city; who had achieved a certain level of independence from the bishops and were not willing to give this power to their new lord. Charles decided to build a heavily fortified castle Vredenburg to house a large garrison with as most important task to maintain order in the city. The castle would last less than 50 years before it was demolished in an uprising in the early stages of the Dutch revolt.

Republic of the Netherlands (1579-1815)

In 1579 the northern seven provinces of these Low Countries signed the Union of Utrecht, in which they decided to join forces against Spanish rule. The Union of Utrecht is seen as the beginning of the Dutch Republic. In 1580 the new and predominantly Protestant state abolished the bishoprics, including the one in Utrecht, which had become an archiepiscopal see in 1559. The stadtholders disapproved of the independent course of the Utrecht bourgeoisie and brought the city under much more direct control of the Holland dominated leadership of the republic. This was the start of a period of stagnation of trade and development in Utrecht.

The city failed to defend itself against the French invasion in 1672, which was held against it in the states of the Republic. The lack of flying buttresses proved to be the undoing of the central section of the cathedral of St Martin church when Utrecht was struck by a tornado in 1674. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 settled the War of the Spanish Succession. Its most lasting result was the cession by Spain of Gibraltar to Great Britain. Since 1723 (but especially after 1870) Utrecht became the centre of the non-Roman Old Catholic Churches in the world.

Modern history (1815-now)

In the early 19th century the role of Utrecht as a fortified town became outdated. The old fortifications were outdated and the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie was moved east of Utrecht. The ramparts could now be demolished to allow for growth. The water defenses remained intact and formed an important feature of the Zocher plantsoen, an English style landscape park that remains largely intact until today.

Growth of the city increased when, in 1843, a railway connecting Utrecht to Amsterdam was opened. After that, Utrecht gradually became the main hub of the Dutch railway network.

In 1853 the Dutch government allowed the bishopric see of Utrecht to be reinstated (by Rome), and Utrecht became the centre of Dutch Catholicism once more.

With the industrial revolution finally gathering speed in the Netherlands and the ramparts taken down, Utrecht began to grow far beyond the medieval center from the 1880s onward with the construction of neighbourhoods such as Oudwijk, Wittevrouwen, Vogelenbuurt to the East, and Lombok to the West. New middle class residential areas, such as Tuindorp and Oog in Al, were built in the 1920s and 1930s. During this period, several Jugendstil houses and office buildings were built, followed by Rietveld who built the Rietveld Schröder House (1924), and Dudok's construction of the city theater (1941).

During World War II, Utrecht was held by the Germans until the general German surrender of the Netherlands on 5 May, 1945. Canadian troops that surrounded the city entered it after that surrender, on May 7, 1945.

Since World War II, the city has grown considerably when new neighbourhoods such as Overvecht, Kanaleneiland, Hoograven, Lunetten, and (recently) Leidsche Rijn were built. Additionally the area surrounding the central station, and the station itself have been developed following modernist ideas of the 1960's, in a brutalist style. This lead to the construction of the shopping mall Hoog Catharijne, music centre Vredenburg (Hertzberger, 1979), and conversion of part of the ancient canal structure into a highway (Catherijnebaan). Protest against further modernisation of the city centre followed even before the last buildings were finalised. In the early 21st century the whole area is being redeveloped

Currently the city is expanding once more with the development of the Leidsche Rijn housing area.

Demographics

Inhabitants of Utrecht are called Utrechter or more rarely Utrechtenaar.[nb 2]

Utrecht city has a population of 296,305 (at 1-1-2007). Utrecht is a growing municipality and projections are that the city will grow beyond 300,000 in 2008; and beyond 350,000 in 2017.[22]

In Utrecht 52% of the population is female, 48% is male. Utrecht has a young population, with many inhabitants in the age category from 20 and 30 years, which is due to the large university.

| Population in Utecht[22] | ||||

| Female | Age | Male | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22761 | 15% | 0-14 | 23994 | 17% |

| 44732 | 30% | 15-29 | 36165 | 26% |

| 36444 | 24% | 30-44 | 39434 | 28% |

| 15574 | 10% | 45-54 | 15996 | 11% |

| 11899 | 8% | 55-64 | 11484 | 8% |

| 8317 | 6% | 65-74 | 7457 | 5% |

| 9374 | 6% | 74+ | 4764 | 3% |

The majority of households (52.5%) in Utrecht is a single person household. About 29% of people living in Utrecht are either married, or have another legal partnership. About 3% of the population of Utrecht is divorced.[22]

About 69% of the population is of Dutch background. About 10% of the population consists of immigrants from western countries. About 21% of the population are immigrants from non-western countries (9% Moroccan, 5% Turkish, 3% Surinamese and Dutch Caribbean and 5% of other non-western countries).[22]

With 9% of its population being of Moroccan heritage, Utrecht hosts (percentually) the largest Moroccan community of all Dutch municipalities.

With 38% percent of its population either earning a minimum income or being dependant on social welfares (17% of all households), Utrecht is known (such as Rotterdam, Amsterdam, The Hague and other major Dutch cities) for its inner-city problems. Boroughs such as Kanaleneiland, Overvecht and Hoograven are built up with, nearly solely, high rise social estates, and are known for relatively high poverty and crime rates, as well as a high percentage of non-Dutch inhabitants (Kanaleneiland: 83%, Overvecht: 57%).

Population centres and Agglomeration

Besides the city of Utrecht, the municipality of Utrecht also includes Vleuten-De Meern, which was a separate municipality until 2001. Vleuten-De Meern in turn included the villages of Haarzuilens and Veldhuizen. Thus the municipality of Utrecht includes several population centres:[23]

- The city of Utrecht (population: app. 258,000)

- Vleuten-De Meern (population: app. 30.000)

- Vleuten

- De Meern

- Haarzuilens

- Veldhuizen

Utrecht is the centre of a densily populated area, which makes concise definitions of its agglomeration difficult, and somewhat arbitrary. The smaller Utrecht agglomeration counts some 420,000 inhabitants and includes Nieuwegein, IJsselstein and Maarssen. It is sometimes argued that the municipalities De Bilt, Zeist, Houten, Vianen, Driebergen-Rijsenburg, and Bunnik should also be counted towards the Utrecht agglomeration, bringing the total to 640,000 inhabitants. The larger region, including slightly more remote towns such as Woerden and Amersfoort counts up to 820,000 inhabitants.[24]

Cityscape

Utrecht is famous for the Dom Tower of Utrecht, belonging to the former cathedral (Dom Church).[25] The city has a minor skyline, dominated by the Dom tower. There has been long standing agreement that no building (height to rooftop) in or near the centre of town may surpass the Dom tower in height (112 m).[26] Nevertheless some tall buildings are now being constructed that will become part of the skyline of Utrecht. The second highest building of the city, the 'Rabobanktoren', will be completed in 2010 and will stand 105 m tall.[27] Two antennas will increase that height to 120 m. Two other buildings are currently under construction around the 'Nieuw Galgenwaard' stadium. These buildings, the 'Kantoortoren Galghenwert' and 'Apollo Residence', will be completed in 2007 and will stand 85.5 and 64.5 metres high respectively. Finally, there are somewhat controversial plans for a 262 m high skyscraper in the newly built neighbourhood of Leidsche Rijn: the 'Belle van Zuylen'.[28] Because the location is considered sufficiently far from the centre of the city this project is exempted from the maximum height of the Dom.

Another landmark are the old centre and the canal structure in the inner city. The Oudegracht is a curved canal, due to its origins as an arm of the Rhine. It is lined with the unique wharf-basement structures that create a two level street along the canals.[29] The inner city has largely retained its Medieval structure,[30] and the moat ringing the old town is largely in tact.[31] Because of the role of Utrecht as a fortified city, that did not allow construction outside the walls, until the 19th century the city has remained very compact. Surrounding the medieval core there is a ring of late 19th and early 20th century neighbourhoods; with newer neighbourhoods positioned farther out.[32] The eastern part of Utrecht remains fairly open. The Dutch Water Line, moved east of the city in the early 19th century required open lines of fire thus prohibiting all permanent constructions until the mid of the 20th century on the east side of the city.[33]

Due to the importance of Utrecht as a religious centre in the past, several monumental churches have survived.[34] Most prominent is the Dom Church. Other notables churches include the romanesque St Peter's and St John's churches, and the gothic churches of St James and St Nicholas, and the so-called Buurkerk, now converted into a museum.

Transport

Because of its central location, the City of Utrecht is well connected to the rest of the Netherlands, and has a well-developed public transport network.

Public transport

Rail connections

Utrecht Centraal is the main railway station of Utrecht. There are also some smaller stations in the suburbs:

-

- Utrecht Lunetten railway station

- Utrecht Overvecht railway station

- Utrecht Terwijde railway station

- Utrecht Zuilen railway station

There is also a museum station for the Dutch Railway Museum, at Utrecht Maliebaan railway station.

From Utrecht Centraal there are:

- Regular Intercity trains to all major Dutch cities, and since March 2006 a direct service to Schiphol Airport.

- International trains (ICE) to Germany.

- Regular Local Trains To Areas all around The Netherlands.

- More Detail at Dutch railway services

A light-rail (sneltram in Dutch) line runs from the Utrecht Centraal station, through the neighbourhoods of Lombok and Kanaleneiland to Nieuwegein and IJsselstein. This line is operated by Connexxion.[35]

Besides being an important node in the transportation system Utrecht hosts the headquarters of both the Nederlandse Spoorwegen (Dutch Railroads), the most important train company in the Netherlands, and ProRail, the state owned company that is responsible for building and maintenance of railroad tracks throughout the Netherlands.[36]

Bus transport

Utrecht Central railway station also operates as the main local and regional bus station.[37] The bus network of Utrecht includes

- Local buses, operated by GVU, including a high-quality bus line to the Uithof university district to the east of the city, served by double-articulated buses.

- Regional Connexxion buses.

- Regional Arriva buses. Arriva also operates buses to Gorinchem and Dordrecht (Q-liner).

- Veolia Transport buses to and from the region northwest of the city, and to Breda and Oosterhout (Interliner).

Utrecht Centraal's bus station is the busiest in the Netherlands.

The Utrecht Central railway station is also frequented by the pan-European Eurolines bus company. Furthermore, it acts as departure and arrival place of many coach companies serving holiday resorts in Spain and France and during winter in Austria and Switzerland.[38]

Other transport

Roads

Utrecht is well connected to the main roads in the Netherlands. Two of the most important major roads cross near Utrecht: The A12 [The Hague - Arnhem - Germany] and the A2 [Amsterdam - Maastricht - Belgium]. Other roads are the A27 [Almere - Breda] and the A28 [Utrecht - Groningen].[39] Due to the increasing traffic, traffic congestion is a common phenomenon in and around Utrecht. This has led to the city being seriously contaminated with particulate dust.[40]

Shipping

Utrecht also has a medium-sized industrial port, located on the Amsterdam-Rhine Canal, which is connected to the Rhine river.[41] The CTU container terminal has a capacity of 80,000 containers a year. In 2003, the port facilitated the transport of four million tons of cargo; mostly sand, gravel, fertilizer, and fodder.[42]

Additionally some touristic boat trips are organised from various places on the Oudegracht.[43]

Economy

The economy of Utrecht depends for a large part on the several large institutions located in the city. Production industry has a relatively small influence in Utrecht. Rabobank, a large bank has its headquarters in Utrecht.

Utrecht is the center of the Dutch railroad network and the location of the head office of the Nederlandse Spoorwegen (Dutch Railways). NS's former head office 'De Inktpot' in Utrecht is the largest brick building in the Netherlands (the "UFO" gracing its facade stems from an art program in 2000). The building is currently used by ProRail.

A large indoor shopping center called Hoog Catharijne (nl) is located between the central railway station and the city center. The corridors have been considered public places like streets, and the main route from station to city center is therefore open all night. Over the next 20 years (counting from 2004), parts of Hoog Catharijne will disappear as a consequence of the renovation of the Station-area[1]. Parts of the city's network of canals, which were filled to create the shopping center and central station area, will be recreated.

At the west side of the central railway station can be found the Jaarbeurs, one of the largest convention centers of the Netherlands.

One of Europe's biggest used car markets is located in the Voordorp district. It is open every Tuesday except on official holidays. With thousands of second-hand vehicles on sale the market is a special point of interest for customers from Eastern European countries who even organize special one-way bus tours for shopping there.

Education

Utrecht is well known for its institutions of higher education. The most prominent of these is Utrecht University (est. 1636), the largest university of The Netherlands with 26,787 students (as of 2004). The University is partially based in the inner city as well as in the Uithof campus area, on the east of the city. According to Shanghai Jiaotong University's university ranking in 2007 it is the 42nd best university in the world.[44] Utrecht also houses the much smaller University of Humanistics (estimated at a few hundred students).

Utrecht is home of one of the locations of TiasNimbas, focused on post-experience management education and the largest management school of its kind in The Netherlands. In 2007, its executive MBA program was rated the 11th best progam in the world by the Financial Times.[45]

Utrecht is also home to two other large institutions of higher education: the Hogeschool Utrecht (30,000 students), with locations in the city and the Uithof campus, and the HKU Utrecht School of the Arts (3,000 students).

There are many schools for primary and secondary education; allowing for different philosophies and religions as is inherent in the Dutch school system. There is some concern about segregation in the primary schools (which is a common problem in many large cities in the Netherlands). This is caused by Dutch parents wanting to send their children to schools with a large proportion of other Dutch children, ending in a spiral where schools with a large proportion of immigrant children attract fewer and fewer Dutch children.

Culture

Utrecht city has an active cultural life, in the Netherlands second only to Amsterdam[5]. Utrecht aims to become cultural capital of Europe in 2018.[46]

There are several theatres and theatre companies. The 1941 main city theater was built by Dudok. Besides theates there is a large number of cinemas including three arthouse cinemas. Utrecht is host to the Netherlands Film Festival. The city has an important classical music hall Vredenburg (1979 by Herman Hertzberger), which acoustics are considered among the best of the 20th century original music halls. Young musicians are educated in the conservatory (a department of the Utrecht School of the Arts). There is a specialised museum of automatically playing musical instruments. Located at the OudeGracht is the rock club Tivoli (which has a second location just outside the centre). There are several other venues for music throughout the city.

There are many art galleries in Utrecht. There are also several foundations to support art, and artists. Training of artists is done at the Utrecht School of the Arts. The Centraal Museum has many exhibitions on the arts, including a permanent exhibition on the works of Utrecht resident illustrator Dick Bruna, who is best known for creating Miffy.

Utrecht also houses one of the landmarks of modern architecture, the 1924 Rietveld Schröder House, which is listed on UNESCO's world heritage sites.

To involve the city population as a whole (rather than the elite alone) in the cultural riches of the city, Utrecht city, in collaboration with the different cultural organisations, regularly organise cultural Sundays. During a thematic Sunday several organisations create a program, which is open to everyone without, or with a very much reduced, admission fee. Furthermore there are many initiatives for amateur artists; e.g. in the performing arts, painting and sculpture. The city subsidises an organisation for amateur education in arts aimed at all inhabitants (Utrechts Centrum voor de Kunsten), as does the University for its staff and students. Additionally there are also several private initiatives. The city council provides coupons for discounts to inhabitants who receive welfare to be used with many of the initiatives.

Utrecht is home to the premier league (professional) football club FC Utrecht, which plays in Stadium Nieuw Galgenwaard. It is also the home of Kampong, the largest (amateur) sportsclub of The Netherlands (4.500 members), SV Kampong. Kampong features fieldhockey, soccer, cricket, tennis, squash and jeu de boules. Kampong's men and women top hockey squads play in the highest Dutch hockey league, the Rabohoofdklasse.

Museums

Utrecht has several smaller and larger museums. Many of those are located in the eastern part of the old town, which is called MuseumQuarter.

- Aboriginal Art Museum Located at the Oude Gracht this museum has a small exhibit of Australian Aboriginal Art

- Centraal Museum Located in the MuseumQuarter this municipal museum has a large collection of art, design, and historical artifacts.

- Dick Bruna Huis Part of Centraal Museum this separate location is dedicated to Miffy creator Dick Bruna

- Museum Catharijneconvent Museum of the Catholic church shows the history of Christian culture and arts in the Netherlands

- National museum 'From musical clock to street organ' National Museum in the centre of the city, displaying several centuries of mechanical musical instruments.

- Railroad Museum Railroad sponsored museum on the history of the Dutch railroads

- University museum Utrecht University museum includes the ancient botanical garden

- Volksbuurtmuseum Wijk C

- Money museum, museum of the Royal Dutch Mint, located in the actual building where Dutch coins are minted.

Famous people from Utrecht

- See also the category People from Utrecht

Over the ages famous people have been born and raised in Utrecht. Among the most famous Utrechters are:

- Pope Adrian VI (1459-1523) - head of the Catholic Church

- C.H.D. Buys Ballot (1817-1890) - meteorologist (Buys-Ballot's law)

- Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) - painter, artist (De Stijl movement)

- Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964) - designer, architect (De Stijl movement)

- Dick Bruna (1923- ) - writer, illustrator (Miffy)

Twin cities

Utrecht has town twinning agreements with the following:

León, Nicaragua

León, Nicaragua Brno, Czech Republic

Brno, Czech Republic Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo- previously

Hannover, Germany, between 1970 and 1976

Hannover, Germany, between 1970 and 1976

See also

- List of mayors of Utrecht

- Utrecht (agglomeration)

- Utrecht (province)

- Ondiep

External links

- Official website of the city

- Mobile website of the city

- CU 2030, redevelopment of the Utrecht Central railroad station area (Dutch only)

Maps

Notes

- ↑ Staatscourant (2007). "Kerngegevens gemeente Utrecht". Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- ↑ CBS statline (2007). "Gemiddelde bevolking per regio naar leeftijd en geslacht / Gebieden in Nederland 2007". Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- ↑ "in Dutch Aartsbisdom Utrecht". Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "in Dutch Katholiek Nederland". Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gemeente Utrecht. "Utrecht Monitor 2007 (in Dutch)". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ Gemeente Utrecht, Geschiedenis Utrecht voor 1528

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 de Bruin, R.E.; T.J. Hoekstra, A. Pietersma (1999). Twintig eeuwen Utrecht, korte geschiedenis van de stad (Dutch). Utrecht, the Netherlands: SPOU & Het Utrechts Archief. ISBN 90-5479-040-7.

- ↑ "History of Utrecht". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ van der Tuuk, Luit (2005). "Denen in Dorestad". in Ria van der Eerden, et al. (in Dutch). Jaarboek Oud Utrecht 2005. Jaarboek Oud Utrecht. Utrecht: SPOU. pp. 5-40. ISBN 90-7108-244.

- ↑ Janssen, H.P.H. (2002) (in Dutch). Geschiedenis van de Middeleeuwen (12th ed.). Utrecht: Aula. pp. 289-296. ISBN 90-274-5377-2.

- ↑ Stöver, R.J. (1997). De Salvator- of Oudmunsterkerk te Utrecht, Stichtingsmonument van het bisdom Utrecht (in Dutch). Utrecht, the Netherlands.

- ↑ "Janskerk Informatie". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ "Sint Pieterskerk Utrecht". Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- ↑ Haverkate, H.M. (1985). Een kerk van papier. De geschiedenis van de voormalige Mariakerk te Utrecht (in Dutch). Zutphen, the Netherlands.

- ↑ Broer, C.J.C. (2000). Uniek in de stad. De oudste geschiedenis van de kloostergemeenschap op de Hohorst sinds 1050 de Sint-Paulusabdij te Utrecht (in Dutch). Utrecht, the Netherlands.

- ↑ "Karel V (in Dutch)". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ "Jacobikerk". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ "Nicolaikerk". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ "Geertekerk - Remonstrantse Gemeente Utrecht". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ "De Utrechtse Werven (Dutch)". Gemeente Utecht. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ "Historic wharf photos from the Utrecht City Archive". Utrecht City Archive. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Gemeente Utrecht. "Bevolkingspublicatie 2007". Retrieved on 2008-04-20.

- ↑ Gemeente Utrecht. "Stad in Cijfers". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ CBS statline (2007). "Gemiddelde bevolking per regio naar leeftijd en geslacht / Gebieden in Nederland 2007". Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

- ↑ RonDom

- ↑ Symposium over hoogbouw in Utrecht, bron: Stichting Hoogbouw - architectenweb.nl

- ↑ Rabobank Groep

- ↑ www.bellevanzuijlen.nl/

- ↑ Utrecht.nl - Cultuurhistorie en Monumenten - De Utrechtse werven

- ↑ Utrecht.nl - Wijksite Binnenstad - De wijk Binnenstad

- ↑ Utrecht

- ↑ Historische Atlas van de stad Utrecht. ISBN 90-8506-189-X

- ↑ Wandelplatform-LAW. Waterliniepad (in Dutch) 1st edition, 2004. ISBN 90-71068-61-7

- ↑ Kerken Kijken Utrecht | Home

- ↑ UrbanRail.Net > Europe > Netherlands > Utrecht Sneltram / Light Rail

- ↑ 404 Pagina niet gevonden › NS reizigers

- ↑ Utrecht.nl - Station area Utrecht - Facelift Utrecht Bus station

- ↑ Travelling to (and inside) Utrecht

- ↑ Autosnelwegen.nl

- ↑ MNP rapport 500037008 Fijn stof nader bekeken

- ↑ Amsterdam-Rhine Canal, or Amsterdam-Rijnkanaal (canal, The Netherlands) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ Container Terminal Utrecht

- ↑ http://vareninutrecht.nl/index.php?page=lp_rondvaart_utrecht http://www.schuttevaer.com/ http://www.inutrechtuit.nl/leuk_en_doen/lovers_rondvaart.html

- ↑ ARWU. "ARWU2007-Top 500 World Universities". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ Financial Times. "FT.com". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ Ublad Online > Peter de Haan promoot Utrecht als culturele hoofdstad van Europa

References

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||