Urinary tract infection

| Urinary tract infection Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

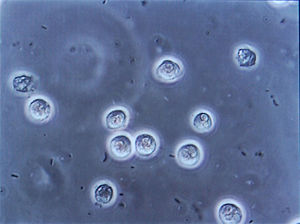

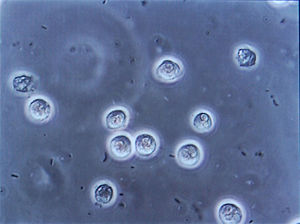

| Multiple rod-shaped bacteria shown between white cells at urinary microscopy from a patient with urinary tract infection. | |

| ICD-10 | N39.0 |

| ICD-9 | 599.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 13657 |

| MedlinePlus | 000521 |

| eMedicine | emerg/625 emerg/626 |

| MeSH | D014552 |

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a bacterial infection that affects any part of the urinary tract. Although urine contains a variety of fluids, salts, and waste products, it usually does not have bacteria in it.[1] When bacteria get into the bladder or kidney and multiply in the urine, they cause a UTI. The most common type of UTI is a bladder infection which is also often called cystitis. Another kind of UTI is a kidney infection, known as pyelonephritis, and is much more serious. Although they cause discomfort, urinary tract infections can usually be quickly and easily treated with a short course of antibiotics.[2] Studies have shown that breastfeeding can reduce the risk of UTI's in infants.[3]

Contents |

Symptoms

For bladder infections

- Frequent urination along with the feeling of having to urinate even though there may be very little urine to pass.

- Nocturia: Need to urinate during the night.

- Urethritis: Discomfort or pain at the urethral meatus or a burning sensation throughout the urethra with urination (dysuria).

- Pain in the midline suprapubic region.

- Pyuria: Pus in the urine or discharge from the urethra.

- Hematuria: Blood in urine.

- Pyrexia: Mild fever

- Cloudy and foul-smelling urine

- Increased confusion and associated falls are common presentations to Emergency Departments for elderly patients with UTI.

- Some urinary tract infections are asymptomatic.

- Protein found in the urine.

For kidney infections

- All of the above symptoms.

- Emesis: Vomiting is common.[4]

- Back, side (flank) or groin pain.

- Abdominal pain or pressure.

- Shaking chills and high spiking fever.

- Night sweats.

- Extreme fatigue.

Epidemiology

UTIs are most common in sexually active women and increase in diabetics and people with sickle-cell disease or anatomical malformations of the urinary tract.

Since bacteria can enter the urinary tract through the urethra (an ascending infection), poor toilet habits can predispose to infection, but other factors (pregnancy in women, prostate enlargement in men) are also important and in many cases the initiating event is unclear.

While ascending infections are generally the rule for lower urinary tract infections and cystitis, the same may not necessarily be true for upper urinary tract infections like pyelonephritis which may be hematogenous in origin.

Allergies can be a hidden factor in urinary tract infections. For example, allergies to foods can irritate the bladder wall and increase susceptibility to urinary tract infections. Keep track of your diet and have allergy testing done to help eliminate foods that may be a problem. Urinary tract infections after sexual intercourse can be also be due to an allergy to latex condoms, spermicides, or oral contraceptives. In this case review alternative methods of birth control with your doctor.

Indwelling urinary catheters in women and men who are elderly, over placement of a temporary Prostatic stent can be a major cause of UTI's. Also, people experiencing nervous system disorders, people who are convalescing or unconscious for long periods of time, will have an increased risk of urinary tract infection for a number of reasons. Scrupulous aseptic techniques may decrease these associated risks.

The bladder wall is coated with various mannosylated proteins, such as Tamm-Horsfall proteins (THP), which interfere with the binding of bacteria to the uroepithelium. As binding is an important factor in establishing pathogenicity for these organisms, its disruption results in reduced capacity for invasion of the tissues. Moreover, the unbound bacteria are more easily removed when voiding. The use of urinary catheters (or other physical trauma) may physically disturb this protective lining, thereby allowing bacteria to invade the exposed epithelium.

Elderly individuals, both men and women, are more likely to harbor bacteria in their genitourinary system at any time. These bacteria may be associated with symptoms and thus require treatment with an antibiotic. The presence of bacteria in the urinary tract of older adults, without symptoms or associated consequences, is also a well recognized phenomenon which may not require antibiotics. This is usually referred to as asymptomatic bacteriuria. The overuse of antibiotics in the context of bacteriuria among the elderly is a concerning and controversial issue.

Women are more prone to UTIs than males because in females, the urethra is much shorter and closer to the anus than in males,[5] and they lack the bacteriostatic properties of prostatic secretions. Among the elderly, UTI frequency is in roughly equal proportions in women and men.

A common cause of UTI is an increase in sexual activity, such as vigorous sexual intercourse with a new partner. The term "honeymoon cystitis" has been applied to this phenomenon.[6]

Diagnosis

A patient with dysuria (painful voiding) and urinary frequency generally has a spot mid-stream urine sample sent for urinalysis, specifically the presence of nitrites, leukocytes or leukocyte esterase. If there is a high bacterial load without the presence of leukocytes, it is most likely due to contamination. The diagnosis of UTI is confirmed by a urine culture.

If the urine culture is negative:

- symptoms of urethritis may point at Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrheae infection.

- symptoms of cystitis may point at interstitial cystitis.

- in men, prostatitis may present with dysuria.

In severe infection, characterized by fever, rigors or flank pain, urea and creatinine measurements may be performed to assess whether renal function has been affected.

Most cases of lower urinary tract infections in females are benign and do not need exhaustive laboratory work-ups. However, UTI in young infants must receive some imaging study, typically a retrograde urethrogram, to ascertain the presence/absence of congenital urinary tract anomalies. Males too must be investigated further. Specific methods of investigation include x-ray, Nuclear Medicine, MRI and CAT scan technology.

Treatment

Most uncomplicated UTIs can be treated with oral antibiotics such as trimethoprim, cephalosporins, nitrofurantoin, or a fluoroquinolone (e.g., ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin). Trimethoprim is probably the most widely used antibiotic for UTIs and is usually taken for 7 days. It is often recommended that trimethoprim be taken at night to ensure maximal urinary concentrations and increase its effectiveness. Whilst co-trimoxazole was previously internationally used (and continues to be used in the U.S.), the additional of the sulfonamide gave little additional benefit compared to the trimethoprim component alone, but was responsible for its high incidence of mild allergic reactions and rare but serious complications.

If the patient has symptoms consistent with pyelonephritis, intravenous antibiotics may be indicated. Regimens vary, usually Aminoglycosides (such as Gentamicin) are used in combination with a beta-lactam, such as Ampicillin or Ceftriaxone. These are continued for 48 hours after fever subsides. The patient may then be discharged home on oral antibiotics for a further 5 days.

If the patient makes a poor response to IV antibiotics (marked by persistent fever, worsening renal function), then imaging is indicated to rule out formation of an abscess either within or around the kidney, or the presence of an obstructing lesion such as a stone or tumor.

As an at-home treatment, increased water-intake, frequent voiding, the avoidance of sugars and sugary foods, drinking unsweetened cranberry juice, taking cranberry supplements, as well as taking vitamin C with the last meal of the day can shorten the time duration of the infection. Sugars and alcohol can feed the bacteria causing the infection, and worsen pain and other symptoms. Vitamin C at night raises the acidity of the urine [7], which retards the growth of bacteria in the urinary tract. However, if pain is in the back region (suggesting kidney infection) or if pain persists, if there is fever, or if blood is present in the urine, doctor care is recommended.

In complementary and alternative medicine, D-mannose pills are advocated as a herbal remedy for urinary tract infections.[8] Theoretically, if D-mannose would be present in sufficient concentration in the urine, it could interfere with the adherence of the bacterium E. coli to the epithelial cells lining the urinary tract (similar to the mechanism underlying the effect of cranberry juice).[9][10] One study showed that it could significantly influence bacteriuria in rats,[11] but there are no studies showing any effect in humans.[8]

Recurrent UTIs

- See also Prevention (below)

Patients with recurrent UTIs may need further investigation. This may include ultrasound scans of the kidneys and bladder or intravenous urography (X-rays of the urological system following intravenous injection of iodinated contrast material). If there is no response to treatments, interstitial cystitis may be a possibility.

During cystitis, uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) subvert innate defenses by invading superficial umbrella cells and rapidly increasing in numbers to form intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs).[12]

Prevention

The following are measures that studies suggest may reduce the incidence of urinary tract infections. These may be appropriate for people, especially women, with recurrent infections:

- Cleaning the urethral meatus (the opening of the urethra) after intercourse has been shown to be of some benefit; however, whether this is done with an antiseptic or a placebo ointment (an ointment containing no active ingredient) does not appear to matter.[13]

- It has been advocated that cranberry juice can decrease the incidence of UTI (some of these opinions are referenced in External Links section). A specific type of tannin found only in cranberries and blueberries prevents the adherence of certain pathogens (eg. E. coli) to the epithelium of the urinary bladder. A review by the Cochrane Collaboration of randomized controlled trials states "some evidence from trials to show cranberries (juice and capsules) can prevent recurrent infections in women. Many people in the trials stopped drinking the juice, suggesting it may not be a popular intervention".[14]

- For post-menopausal women, a randomized controlled trial has shown that intravaginal application of topical estrogen cream can prevent recurrent cystitis.[15] In this study, patients in the experimental group applied 0.5 mg of estriol vaginal cream nightly for two weeks followed by twice-weekly applications for eight months.

- Often long courses of low dose antibiotics are taken at night to help prevent otherwise unexplained cases of recurring cystitis.

- Acupuncture has been shown to be effective in preventing new infections in recurrent cases.[16][17][18] One study showed that urinary tract infection occurrence was reduced by 50% for 6 months.[19] However, this study has been criticized for several reasons.[20] Acupuncture appears to reduce the total amount of residual urine in the bladder . All of the studies are done by one research team without independent reproduction of results.

References

- ↑ "Adult Health Advisor 2005.4: Bacteria in Urine, No Symptoms (Asymptomatic Bacteriuria)". Retrieved on 2007-08-25.

- ↑ "Urinary Tract Infections". Retrieved on 2007-08-25.

- ↑ Hanson, LÅ (2004). "Protective effects of breastfeeding against urinary tract infection". Acta Pædiatr (93): 154–156. ISSN 0803-5253. http://www.cirp.org/library/disease/UTI/hanson1/. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- ↑ askdrsears.com

- ↑ Urethra length is approximately 25–50 mm / 1-2 inches long in females, versus about 20 cm / 8 inches in males.

- ↑ "Honeymoon Cystitis". Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ↑ What I need to know about Urinary Tract Infections Accessed December 5, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Urinary Tract Infection - Alternative medicine. Accessed October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Sharon N, Eshdat Y, Silverblatt FJ, Ofek I (1981). "Bacterial adherence to cell surface sugars". Ciba Foundation symposium 80: 119–41. PMID 6114817.

- ↑ Toyota S, Fukushi Y, Katoh S, Orikasa S, Suzuki Y (December 1989). "[Anti-bacterial defense mechanism of the urinary bladder. Role of mannose in urine]" (in Japanese). Nippon Hinyōkika Gakkai zasshi. The japanese journal of urology 80 (12): 1816–23. PMID 2576290.

- ↑ Michaels EK, Chmiel JS, Plotkin BJ, Schaeffer AJ (1983). "Effect of D-mannose and D-glucose on Escherichia coli bacteriuria in rats". Urological research 11 (2): 97–102. PMID 6346629.

- ↑ Justice S, Hunstad D, Seed P, Hultgren S (2006). "Filamentation by Escherichia coli subverts innate defenses during urinary tract infection". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 (52): 19884–9. doi:. PMID 17172451.

- ↑ Meyhoff H, Nordling J, Gammelgaard P, Vejlsgaard R (1981). "Does antibacterial ointment applied to urethral meatus in women prevent recurrent cystitis?". Scand J Urol Nephrol 15 (2): 81–3. PMID 7036332.

- ↑ RG Jepson, JC Craig (2008). "Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001321. PMID 14973968.

- ↑ Raz R, Stamm W (1993). "A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections.". N Engl J Med 329 (11): 753–6. doi:. PMID 8350884.

- ↑ Aune A, Alraek T, Huo L, Baerheim A (1998). "[Can acupuncture prevent cystitis in women?]". Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 118 (9): 1370–2. PMID 9599500. (cf acupuncture group, x2 incidents in the sham group, x3 in the control group)

- ↑ Alraek T, Baerheim A (2001). "'An empty and happy feeling in the bladder.. .': health changes experienced by women after acupuncture for recurrent cystitis". Complement Ther Med 9 (4): 219–23. doi:. PMID 12184349.

- ↑ Alraek T, Baerheim A (2003). "The effect of prophylactic acupuncture treatment in women with recurrent cystitis: kidney patients fare better". J Altern Complement Med 9 (5): 651–8. doi:. PMID 14629843. (highlights need for considering different TCM diagnostic categories in acupuncture research)

- ↑ Alraek T, Soedal L, Fagerheim S, Digranes A, Baerheim A (2002). "Acupuncture treatment in the prevention of uncomplicated recurrent lower urinary tract infections in adult women.". Am J Public Health 92 (10): 1609–11. PMID 12356607.

- ↑ Katz AR (2003). "Urinary tract infections and acupuncture". Am J Public Health 93 (5): 702; author reply 702–3. PMID 12721123.

See also

- Nosocomial infection

- vulvovaginal health

External links

- NIH articles on Urinary Tract Infections in Adults and in Children.

- MedlinePlus Overview urinarytractinfections

- Urinary tract infection at GPnotebook

- Urinary tract infection at the Open Directory Project

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||