Union between Sweden and Norway

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History of Sweden |

|---|

| Scandinavian prehistory (–800) |

| Viking and Middle ages (800–1521) |

| Early Vasa era (1521–1611) |

| Emerging Great Power (1611–1648) |

| Swedish Empire (1648–1718) |

| Age of Liberty (1718–1772) |

| Absolutism of Gustavus III (1772–1809) |

| Union with Norway (1814–1905) |

| Oscarian era (late 19th century) |

| Industrialization (1870s–1930) |

| World War II (1930s–1945) |

| Cold war Sweden (1945–1989) |

| Post–Cold War (1989–) |

| Topical |

| Military history |

| This article is part of the Scandinavia series |

|---|

| Geography |

|

| The Viking Age |

|

| Political entities |

|

| History |

| Other |

|

The Union between Sweden and Norway (Swedish: Svensk-norska unionen, Unionen mellan Sverige och Norge, Norwegian: Unionen mellom Norge og Sverige), was the union of the kingdoms of Sweden and Norway between 1814 and 1905, when they were united under one monarch in a personal union, following the Treaty of Kiel, the declaration of Norwegian independence, a brief war with Sweden, the Convention of Moss, on August 14, 1814, and the Norwegian constitutional revision of November 4, 1814. On the same day, the Norwegian parliament elected the Swedish king Charles XIII king of Norway.

Contents |

Early history

Sweden and Norway had previously been united under the same crown on two occasions, from 1319 to 1343, and briefly from 1449 to 1450 in opposition to Christian of Oldenburg who was elected king of the Kalmar Union by the Danes.

Act of Union

The Act of Union, which was given royal assent on August 6, 1815, was implemented differently in the two countries. In Norway it was a part of constitutional law known as Rigsakten, and in Sweden it was a set of provisions under regular law and was known as Riksakten. The Congress of Vienna, which oversaw numerous territorial changes in post Napoleonic Europe, did not discuss the union of the Norwegian and Swedish crowns. The Norwegian possessions of the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland had remained with Denmark as a result of the Treaty of Kiel.

Norwegian discontent

Norway was a reluctant member of the union. One manifestation of this was that Norwegian history and culture were glorified in the literature of the period. Norwegian farm culture served as a symbol and focus of nationalistic resistance to the forced union with Sweden. A growing sense of nationalism also influenced political affairs.[3]

One significant political step, the development of the Norwegian local self-government district known as the Formannskapsdistrikt, was approved by Stortinget and signed into law by Charles XIV of Sweden and Norway on January 14, 1837.[4] The law, required by the Constitution of Norway, mandated that every parish (in Norwegian prestegjeld[5]) form a formannsskapsdistrikt. In this manner the Norwegian State Church districts of the country became administrative districts as well, creating 373 formannsskapsdistrikt in 1837.[6]

This introduction of self-government in rural districts was a major political watershed. The legislation of 1837 gave both the towns and the rural areas the same institutions; it represented a minor change for the town, but a major advance for the rural communities and an advance for Norwegian nationalism.[3]

Dissolution of the Union

Following growing dissatisfaction with the union in Norway, the parliament unanimously declared its dissolution on June 7, 1905. This unilateral action met with Swedish threats of war. A plebiscite on August 13 confirmed the parliamentary decision by a majority of 368,208 to 184. Negotiations in Karlstad led to agreement with Sweden September 23 and mutual demobilization. Both parliaments revoked the Act of Union October 16, and the King Oscar II of Sweden renounced his claim to the Norwegian throne and recognized Norway as an independent kingdom on October 26.

The Norwegian parliament offered the vacant throne to Prince Carl of Denmark, who accepted after another plebiscite had confirmed the monarchy. He arrived in Norway on November 25, 1905, taking the name Haakon VII.

A new dynasty

- See also: Charles XIV John of Sweden

Charles XIII was both infirm and childless. To secure the succession to the throne, he adopted Prince Christian August of Augustenborg as his heir. Christian August had been viceroy of Norway and commander-in-chief of the Norwegian army during its successful resistance against the Swedish invasion in 1808–09. His great popularity in Norway was considered an advantage to the Swedish plans for the acquisition of that country. In addition, he had demonstrated his interest in a rapprochement between the two countries by refraining from invading Sweden during the conflict with the Russian Empire. As crown prince of Sweden, he changed his name to Carl August of Augustenborg. After his mysterious death on May 28, 1810, the French marshal Bernadotte (later to become Charles XIV John) was adopted by Charles XIII and received the homage of the estates on November 5, 1810.

The new crown prince was very soon the most popular and the most powerful man in Sweden. The infirmity of the old king, and the dissensions in the Privy Council, placed the government and especially the control of foreign affairs almost entirely in his hands. He boldly adopted a policy which was antagonistic indeed to the wishes and hopes of the old school of Swedish statesmen, but perhaps the best adapted to the circumstances.The Grand Duchy of Finland he at once gave up for lost; he knew that Russia would never voluntarily relinquish it while Sweden could not hope to retain it permanently, even if she reconquered it. But the acquisition of Norway might make up for the loss of Finland; and Bernadotte, now known as the crown prince Charles John or "Karl Johan", argued that it might be an easy matter to persuade the anti-Napoleonic powers to punish Denmark for her loyalty to the First French Empire by wrestling Norway from her.

Napoleon I of France he rightly distrusted, though at first he was obliged to submit to the emperor's dictation. Thus on November 13, 1810 the Swedish government was forced to declare war against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, though the British government under Spencer Perceval was privately informed at the same time that Sweden was not a free agent and that the war would be a mere demonstration. But the pressure of Napoleon became more and more intolerable, culminating in the occupation of Pomerania by French troops in 1812. The Swedish government thereupon concluded a secret convention with Russia, the Treaty of Saint Petersburg, April 5, 1812 undertaking to send 30,000 men to operate against Napoleon in Germany in return for a promise from Alexander I of Russia guaranteeing to Sweden the possession of Norway. Too late Napoleon endeavoured to outbid Alexander by offering to Sweden Finland, all Pomerania and Mecklenburg, in return for Sweden's active co-operation against Russia.

The Örebro Riksdag (April-August, 1812), remarkable besides for its partial repudiation of Sweden's national debt and its reactionary press laws, introduced general conscription into Sweden, and thereby enabled the crown prince to carry out his ambitious policy. In May 1812 he mediated a peace between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, so as to enable Russia to use all her forces against France (the Treaty of Bucharest); and on July 18, at Örebro, peace was also concluded between the United Kingdom on one side and Russia and Sweden on the other.

These two treaties were, in effect, the cornerstones of a fresh coalition against Napoleon, and were confirmed on the outbreak of the Franco-Russian War by a conference between Alexander and Charles John at Åbo on August 30, 1812 when the tsar undertook to place an army corps of 35,000 men at the disposal of the Swedish crown prince for the conquest of Norway.

Personal union with Norway

The Treaty of Åbo, and indeed the whole of Charles John's foreign policy in 1812, provoked violent and justifiable criticism among the better class of politicians in Sweden. The immorality of indemnifying Sweden at the expense of a weaker friendly power was obvious; and, while Finland was now definitively sacrificed, Norway had still to be won.

Moreover, the United Kingdom and Russia very properly insisted that Charles John's first duty was to the anti-Napoleonic coalition, the former power vigorously objecting to the expenditure of her subsidies on the nefarious Norwegian adventure before the common enemy had been crushed. Only on his very ungracious compliance did the United Kingdom also promise to countenance the union of Norway and Sweden (Treaty of Stockholm, March 3, 1813); and, on April 23, Russia gave her guarantee to the same effect.

The Swedish crown prince rendered several important services to the allies during the campaign of 1813 but, after Leipzig, he went his own way, determined at all hazards to cripple Denmark and secure Norway. The Norwegians themselves were opposed to this, and a short war broke out forcing the Swedish to settle for a personal union of two equal countries, rather than annexing Norway as originally intended. The terms were laid down at the Convention of Moss. On November 4, 1814, the parliament of Norway revised the constitution and elected Charles XIII of Sweden as the new king of Norway.

The royal house of Bernadotte

Charles XIII of Sweden died on February 5, 1818, and was succeeded by Bernadotte under the title of Charles XIV John. The new king devoted himself to the promotion of the material development of the country, with the Göta Canal absorbing the greater portion of the twenty-four million the Riksdaler voted for the purpose. The external debt of Sweden was gradually extinguished, the internal debt considerably reduced, and the budget showed an average annual surplus of 700,000 Riksdaler. With returning prosperity the necessity for internal reform became urgent in Sweden.

The antiquated Riksdag of the Estates, where the privileged estates predominated, while the cultivated middle class was practically unrepresented, had become an insuperable obstacle to all free development; but though the Riksdag of 1840 itself raised the question of reform, the king and the aristocracy refused to entertain it. Yet the reign of Charles XIV was, on the whole, most beneficial to Sweden; and if there was much just cause for complaint, his great services to his adopted country were generally acknowledged. Abroad he maintained a policy of peace based mainly on a good understanding with Russia.

Oscar I

Charles XIV's son and successor King Oscar I was much more liberally inclined. Shortly after his accession on March 4, 1844 he laid several projects of reform before the Riksdag, many of which had been prepared by the liberal jurist Johan Gabriel Richert. However, the estates would do little more than abolish the obsolete marriage and inheritance laws and a few commercial monopolies. As the financial situation necessitated a large increase of taxation, there was much popular discontent, which culminated in riots in the streets of Stockholm March 1848. Yet, when fresh proposals for parliamentary reform were laid before the Riksdag in 1849, they were again rejected by three out of the four estates.

As regards foreign politics, Oscar I was strongly anti-German. On the outbreak of the Dano-Prussian War of 1848-1849, Sweden sympathized warmly with Denmark. Hundreds of Swedish volunteers hastened to Schleswig-Holstein. The Riksdag voted 2,000,000 Riksdaler for additional armaments. It was Sweden, too, who mediated the Truce of Malmö on August 26, 1848 which helped Denmark out of her difficulties. During the Crimean War Sweden remained neutral, although public opinion was decidedly anti-Russian, and sundry politicians regarded the conjuncture as favourable for regaining Finland.

Charles XV

Oscar I was succeeded on July 8, 1859 by his son, Charles XV, who had already acted as regent during his father's illnesses. He succeeded, with the invaluable assistance of the minister of justice, Baron Louis De Geer, in at last accomplishing the much-needed reform of the constitution. The way had been prepared in 1860 by a sweeping measure of municipal reform; and, in January 1863, the government brought in a reform bill by the terms of which the Riksdag was henceforth to consist of two chambers, the Upper House being a sort of aristocratic senate, while the members of the Lower House were to be elected triennially by popular suffrage.

The new constitution was accepted by all four estates in 1865 and promulgated on January 22, 1866. On September 1, 1866, the first elections under the new system were held; and on January 19, 1867, the new Riksdag met for the first time. With this one great reform Charles XV had to be content; in all other directions he was hampered, more or less, by his own creation. The Riksdag refused to sanction his favourite project of a reform of the Swedish army on the Prussian model, for which he laboured all his life, partly from motives of economy, partly from an apprehension of the king's martial tendencies.

In 1864 Charles XV had endeavoured to form an anti-Prussian league with Denmark; and after the defeat of Denmark he projected a Scandinavian Union, in order, with the help of France, to oppose Prussian predominance in the north - a policy which naturally collapsed with the overthrow of the French Empire in 1870. He died on September 18, 1872 and was succeeded by his brother, the duke of Östergötland, who reigned as Oscar II.

State of the Union

The relations with Norway during King Oscar's reign had great influence on political life in Sweden, and more than once it seemed as if the union between the two countries was on the point of being wrecked. The dissensions chiefly had their origin in the demand by Norway for separate consuls and eventually a separate foreign service. Norway had, according to the constitution of 1814, the right to separate consular offices, but had not exercised that right partly for financial reasons, partly because the consuls appointed by the Swedish foreign office generally did a satisfactory job of representing Norway.

At last, after vain negotiations and discussions, the Swedish government in 1895 gave notice to Norway that the commercial treaty which until then had existed between the two countries would lapse in July 1897 and would, according to a decision in the Riksdag, cease, and as Norway at the time had raised the customs duties, a considerable diminution in the exports of Sweden to Norway took place. Count Lewenhaupt, the Swedish minister of foreign affairs, who was considered to be too friendly towards the Norwegians, resigned and was replaced by Count Ludvig Douglas, who represented the opinion of the majority in the First Chamber. However, when the Norwegian Storting, for the third time, passed a bill for a national or "pure" flag, which King Oscar eventually sanctioned, Count Douglas resigned in his turn and was succeeded by the Swedish minister at Berlin, Lagerheim, who managed to pilot the questions of the union into more quiet waters.

He succeeded all the better as the new elections to the Riksdag of 1900 showed clearly that the Swedish people were not inclined to follow the ultraconservative or so-called "patriotic" party, which resulted in the resignation of the two leaders of that party, Professor Oscar Alin and Count Marshall Patrick Reutersvärd as members of the First Chamber. On the other hand, ex-Professor E. Carlson, of the Gothenburg University, succeeded in forming a party of Liberals and Radicals to the number of about 90 members, who besides being in favour of the extension of the franchise, advocated the full equality of Norway with Sweden in the management of foreign affairs.

The state of quietude which for some time prevailed with regard to the relations with Norway was not, however, to be of long duration. The question of separate consuls for Norway soon came up again. In 1902 the Swedish government proposed that negotiations in this matter should be opened with the Norwegian government, and that a joint committee, consisting of representatives from both countries, should be appointed to consider the question of a separate consular service without in any way interfering with the existing administration of the diplomatic affairs of the two countries.

The result of the negotiations was published in a so-called "communiqué", dated March 24, 1903 in which, among other things, it was proposed that the relations of the separate consuls to the joint ministry of foreign affairs and the embassies should be arranged by identical laws, which could not be altered or repealed without the consent of the governments of both countries. The proposal for these identical laws, which the Norwegian government in May 1904 submitted, did not meet with the approval of the Swedish government. The latter in their reply proposed that the Swedish foreign minister should have such control over the Norwegian consuls as to prevent the latter from exceeding their authority.

However, the Norwegian government found this proposal unacceptable, and explained that, if such control were insisted upon, all further negotiations would be purposeless. They maintained that the Swedish demands were incompatible with the sovereignty of Norway, as the foreign minister was a Swede and the proposed Norwegian consular service, as a Norwegian institution, could not be placed under a foreign authority. A new proposal by the Swedish government was likewise rejected, and in February 1905 the Norwegians broke off the negotiations. Notwithstanding this an agreement did not appear to be out of the question. All efforts to solve the consular question by itself had failed, but it was considered that an attempt might be made to establish separate consuls in combination with a joint administration of diplomatic affairs on a full unionistic basis.

Crown Prince Gustaf, who during the illness of King Oscar was appointed regent, took the initiative of renewing the negotiations between the two countries, and on April 5 in a combined Swedish and Norwegian Council of State made a proposal for a reform both of the administration of diplomatic affairs and of the consular service on the basis of full equality between the two kingdoms, with the express reservation, however, of a joint foreign minister — Swedish or Norwegian — as a condition for the existence of the union. This proposal was approved of by the Swedish Riksdag on May 3, 1905. In order that no obstacles should be placed in the way for renewed negotiations, Erik Gustaf Boström, the Prime Minister, resigned and was succeeded by Johan Ramstedt. The proposed negotiations were not, however, renewed.

Dissolution of the Union

On May 23, the Norwegian Storting passed the government's proposal for the establishment of separate Norwegian consuls, and as King Oscar, who again had resumed the reins of government, made use of his constitutional right to veto the bill, the Norwegian ministry tendered their resignation. The king, however, declared he could not now accept their resignation, whereupon the ministry at a sitting of the Norwegian Storting on June 7 placed their resignation in its hands.

The Storting thereupon unanimously adopted a resolution stating that, as the king had declared himself unable to form a government, the constitutional royal power "ceased to be operative", whereupon the ministers were requested, until further instructions, to exercise the power vested in the king, and as King Oscar thus had ceased to act as "the king of Norway", the union with Sweden was in consequence dissolved.

In Sweden, where they were least of all prepared for the turn things had taken, the action of the Storting created the greatest surprise and resentment. The king solemnly protested against what had taken place and summoned an extraordinary session of the Riksdag for June 20 to consider what measures should be taken, with regard to the question of the union, which had arisen suddenly through the revolt of the Norwegians on June 7.

The Riksdag declared that it was not opposed to negotiations being entered upon regarding the conditions for the dissolution of the union if the Norwegian Storting, after a new election, made a proposal for the repeal of the Act of Union between the two countries, or if a proposal to this effect was made by Norway after the Norwegian people, through a plebiscite, had declared in favour of the dissolution of the union. The Riksdag further resolved that 100 million kronor should be held in readiness and be available as the Riksdag might decide. On the resignation of the Ramstedt ministry Mr. Lundeberg formed a coalition ministry consisting of members of the various parties in the Riksdag, after which the Riksdag was prorogued on August 3.

After the plebiscite in Norway on the August 13 had decided in favour of the dissolution of the union with 368,392 votes against 184 votes, and after the Storting had requested the Swedish government to co-operate with it for the repeal of the Act of Union, a conference of delegates from both countries was convened at Karlstad on August 31. On September 23 the delegates came to an agreement, the principal points of which were: that such disputes between the two countries which could not be settled by direct diplomatic negotiations, and which did not affect the vital interests of either country, should be referred to the permanent court of arbitration at The Hague, that on either side of the southern frontier a neutral zone of about fifteen kilometres width should be established, and that within eight months the fortifications within the Norwegian part of the zone should be destroyed.

Other clauses dealt with the rights of the Laplanders to graze their reindeer alternatively in either country, and with the question of transport of goods across the frontier by rail or other means of communication, so that the traffic should not be hampered by any import or export prohibitions or otherwise.

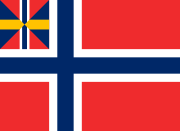

From October 2 to October 19, the extraordinary Riksdag was again assembled, and eventually approved of the arrangement come to by the delegates at Karlstad with regard to the dissolution of the union as well ordinary as the government proposal for the repeal of the Act of Union and the recognition of Norway as an independent state. An alteration in the Swedish flag was also decided upon, by which the mark of union was to be replaced by an azure-blue square.

An offer from the Norwegian Storting to elect a prince of the Swedish royal house as king in Norway was declined by King Oscar, who now on behalf of himself and his successors renounced the right to the Norwegian crown. Mr Lundeberg, who had accepted office only to settle the question of the dissolution of the union, now resigned and was succeeded by a Liberal government with Mr Karl Staaff as prime minister.

See also

- Union Dissolution Day

- History of Norway

- History of Denmark

- History of Sweden

- History of Scandinavia

- Union badge of Norway and Sweden

- Kalmar Union

- Denmark-Norway

Notes

- ↑ Tacitus.no - Skandinaviens befolkning (in Swedish)

- ↑ SSB - 100 års ensomhet? Norge og Sverige 1905-2005 (in Norwegian)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Derry, T.K. (1973). A History of Modern Norway; 1814–1972. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-822503-2.

- ↑ Gjerset, Knut (1915). History of the Norwegian People, Volumes II. The MacMillan Company. ISBN none.

- ↑ Prestegjeld is a geographic and administrative district in the Norwegian State Church.

- ↑ Derry, T.K. (1960). A Short History of Norway. George Allen & Unwin. ISBN none.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.