Ulster Unionist Party

| Ulster Unionist Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Sir Reg Empey MLA |

| Founded | 1905 |

| Headquarters | 429 Holywood Road Belfast, BT4 2LN Northern Ireland, United Kingdom |

| Political Ideology | Ulster unionism, Centrism |

| Political Position | Centre, Unionist |

| International Affiliation | none |

| European Affiliation | Movement for European Reform |

| European Parliament Group | ED, within EPP-ED |

| Colours | Red, White and Blue |

| Website | http://www.uup.org |

| See also | Politics of the UK Political parties |

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP, sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or OUP or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party) is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland.[1] Prior to the split in Unionism in the late 1960s, when the Protestant Unionist Party began to attract more hard line support away from the UUP, it governed Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972 as the sole Unionist party. It continued to be supported by most unionist voters throughout the period known as the Troubles.

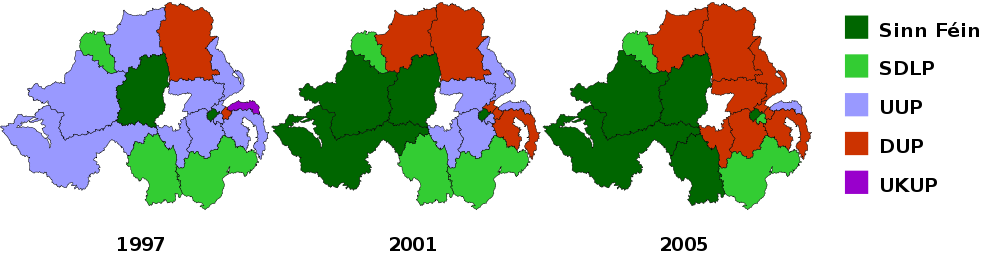

The UUP has lost support among Northern Ireland's unionist and Protestant community to the more 'hardline' Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in successive elections at all levels of government since 1999. The party is currently led by Sir Reg Empey.

In 2008, the party announced it was moving towards closer ties with the Conservative Party. The move will involve standing joint candidates in Northern Ireland and will see UUP MPs serve in Conservative governments, where UUP MPs will work with the Conservatives. The situation would recapitulate that of its own former relationship with the Conservatives and that of the Scottish Unionist Party prior to its merger to form the current Conservative Party.[2]

Contents |

Party leaders

- Colonel Saunderson 1905–1906**

- Viscount Long 1906–1910**

- Sir Edward Carson 1910–1921**

- Viscount Craigavon 1921–1940

- John Miller Andrews 1940–1946

- Viscount Brookeborough 1946–1963

- Captain Terence O'Neill 1963–1969

- Major James Chichester-Clark 1969–1971

- Brian Faulkner 1971–1974

- Harry West 1974–1979

- James Molyneaux 1979–1995

- David Trimble 1995–2005

- Sir Reg Empey 2005–present

- note: ** denotes leaders of the UUP who were also leaders of the Irish Unionist Parliamentary Party.

History

1880s to 1921

The Ulster Unionist Party traces its formal existence back to the foundation of the Ulster Unionist Council in 1905. Prior to that, however, there had been a less formally organised Irish Unionist Party since the late 19th century, sometimes but not always dominated by Unionists from Ulster. Modern organised Unionism properly emerged after William Gladstone's introduction in 1886 of the first of three Home Rule Bills in response to demands by the Irish Parliamentary Party. The Irish Unionist Party was an alliance of Conservatives and Liberal Unionists, the latter having split from the Liberal Party over the issue of home rule. It is this split that gave rise to the current name of the Conservative and Unionist Party, to which the UUP was formally linked to varying degrees until 1985.

The party had a strong association with the Orange Order, a Protestant religious institution. The original composition of the Ulster Unionist Council was 50% Orange delegates, however this was reduced through the years. Though most unionist support was based in the geographic area that became Northern Ireland, there were at one time Unionist enclaves throughout southern Ireland. Unionists in Cork and Dublin were particularly influential. The initial leadership of the Unionist Party all came from outside the six counties of Ulster, with people such as Colonel Saunderson, Viscount (later the Earl of) Midleton and the Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson, members of the Irish Unionist Party. However, after the Irish Convention failed to reach an understanding on home rule and with the partition of Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, Irish unionism in effect split. Many southern unionist politicians quickly became reconciled with the new Irish Free State, sitting in its senate or joining its political parties. Unionism's northern wing evolved into the separate Ulster Unionist Party.

The leadership of the UUP was taken by Edward Carson in 1910. Throughout his 11 year leadership he fought a sustained campaign against Irish Home Rule, including the formation of the Ulster Volunteers in 1912. During the various Home Rule crises, Carson moved from being MP for Dublin University to Belfast Duncairn, however the compromise of Irish partition was felt by Carson to be defeat, so he refused the opportunity to be Prime Minister of Northern Ireland or even to sit in the Northern Ireland House of Commons. The leadership of the Party and, subsequently, Northern Ireland was taken by Sir James Craig.

The Stormont era

Until almost the very end of its period of power in Northern Ireland the Unionist Party was led by a combination of landed gentry (Lord Brookeborough and James Chichester-Clark), aristocracy (Terence O'Neill) and gentrified industrial magnates (Lord Criagavon and John Miller Andrews — nephew of Viscount Pirrie). Only its last Prime Minister, Brian Faulkner was from a middle-class background.

Lord Craigavon governed Northern Ireland from its inception until his death in 1940 and is buried with his wife by the east wing of Parliament Buildings. His successor, J. M. Andrews, was heavily criticised for appointing octogenarian veterans of Craigavon's administration to his cabinet. His government was also believed to be more interested in protecting the statue of Carson at the Stormont Estate than the citizens of Belfast during the Blitz. A backbench revolt in 1943 resulted in his resignation to be replaced by Sir Basil Brooke (later Viscount Brookeborough), although he was recognised as leader of the party until 1946.

Brookeborough, despite having felt that Craigavon had held on to power for too long, was Prime Minister for one year longer. During this time he was on more than one occasion called to meetings of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland to explain his actions, most notably following the 1947 Education Act which made the state responsible for the payment of National Insurance contributions of teachers in Catholic Maintained Schools. Ian Paisley called for Brookeborough's resignation in 1953 when he refused to sack Brian Maginess and Sir Clarence Graham, Bt. who gave speeches supporting Catholic membership of the UUP. He retired in 1963 and was replaced by Terence O'Neill, who emerged ahead of other candidates, Jack Andrews and Faulkner.

In the 1960s, identifying with the civil rights movement of Martin Luther King and encouraged by attempts at reform under O'Neill, the Northern Civil Rights Movement campaigned for legislation that would end discrimination against Catholics in a number of areas, including the allocation of public housing and the local government franchise (which was restricted to rate payers). O'Neill had pushed through some reforms but in the process the Ulster Unionists became heavily divided. At the 1969 Stormont General Election UUP candidates stood on both pro and anti-O'Neill platforms, with several independent pro-O'Neill Unionists challenging his critics, whilst the Protestant Unionist Party of Ian Paisley mounted a hard-line challenge. The result proved inconclusive for O'Neill, who resigned a short time later. His resignation was probably caused by that of James Chichester-Clark who stated that he disagreed with the timing, but not the principle, of universal suffrage at Local Elections.

Chichester-Clark won the leadership election to replace O'Neill and swiftly moved to implement many of his reforms. Civil disorder continued to mount, culminating in August 1969 when republicans clashed with Apprentice Boys in Derry, sparking days of riots, and decades of violence. Early in 1971 Chichester-Clark flew to London to request further military aid following the murder of three off duty soldiers by the IRA. When this was all but refused, he resigned to be replaced by Brian Faulkner.

Faulkner's government struggled though 1971 and into 1972, however following Bloody Sunday the British Government threatened to remove security primacy from the devolved Government. Faulkner reacted by resigning with his entire cabinet, and the Government suspended, and eventually abolished the Northern Ireland Parliament.

The liberal Unionist group the New Ulster Movement, who had advocated the policies of Terence O'Neill left and formed the Alliance Party in April 1970, while the emergence of Ian Paisley's Protestant Unionist Party drew off some working-class and more hard-line support.

1972–1995

In June 1973 the Unionists won a majority of seats in the new Northern Ireland Assembly, but the party was divided on policy. The Sunningdale Agreement, which led to the formation of a power-sharing Executive under the Ulster Unionist leader Brian Faulkner, ruptured the party. In the 1973 elections to the Executive the party found itself divided, a division that did not formally end until January 1974 with the triumph of the anti-Sunningdale faction. Faulkner was then overthrown, and he set up the Unionist Party of Northern Ireland (UPNI). The Ulster Unionists were now led by Harry West from 1974 until 1979. In the February 1974 general election, the party participated in the United Ulster Unionist Coalition (UUUC) with Vanguard and the Democratic Unionists. The result was that the UUUC won 11 out of 12 parliamentary seats in Northern Ireland on a fiercely anti-Sunningdale platform, although they barely won 50% of the overall popular vote. This result was a fatal blow for the Executive, which soon collapsed.

Up until 1974 the UUP was affiliated with the National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations, and Ulster Unionist MPs sat with the Conservative Party at Westminster, traditionally taking the Conservative parliamentary whip. To all intents and purposes the party functioned as the Northern Ireland branch of the Conservative Party. In 1974, in protest over the Sunningdale Agreement, the Westminster Ulster Unionist MPs withdrew from the alliance. The party remained affiliated to the National Union but in 1985, they withdrew from it as well, in protest over the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Subsequently, the Conservative Party has organised separately in Northern Ireland, with little electoral success.

Under West's leadership, the party recruited Enoch Powell, who became Ulster Unionist MP for South Down. Powell advocated a policy of integration, whereby Northern Ireland would be administered as an integral part of the United Kingdom. This policy divided both the Ulster Unionists and the wider Unionist movement, as Powell's ideas conflicted with those supporting a restoration of devolved government to the province. The party also made gains upon the breakup of the Vanguard Party and its merger back into the Ulster Unionists. The separate United Ulster Unionist Party (UUUP) emerged from the remains of Vanguard but folded in the early 1980s, as did the UPNI. In both cases the main beneficiaries of this were the Ulster Unionists, now under the leadership of James Molyneaux (1979–95).

The Trimble Leadership

David Trimble led the party between 1995 and 2005. His support (which some nationalists claim to be ambiguous) for the Belfast Agreement caused a rupture within the Party into pro-agreement and anti-agreement factions. Trimble served as First Minister of Northern Ireland in the power-sharing administration created under the Belfast Agreement.

The UUP had a Roman Catholic Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) (the Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly), Sir John Gorman until the 2003 election. In March 2005, the Orange Order voted to end its official links with the UUP, while still maintaining the same unofficial links as other interest groups. Mr Trimble faced down Orange Order critics who tried to suspend him for his attendance at a Catholic funeral for a young boy murdered by the Real IRA, in the infamous Omagh bombing. Trimble and Irish president Mary McAleese, in a sign of unity, walked into the church together.

2005 General Election

The party fared poorly in the 2005 general election, losing five of its six Westminster seats — one MP had previously defected to the DUP. Only the Labour Party lost more seats in 2005. David Trimble himself lost his seat in Upper Bann and resigned as party leader soon after. The ensuing leadership election was won by Sir Reg Empey.

2005 - present

In May 2006 UUP leader Reg Empey attempted to create a new assembly group that would have included Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) leader David Ervine. The PUP is the political wing of the illegal Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF),[3][4][5][6][7] a paramilitary organisation that carried out many murders during the Troubles and equivalent to the Provisional Irish Republican Army for the Sinn Féin Party. Many in the UUP, including the last remaining MP, Sylvia Hermon, were opposed to the move.[8][9] The link was in the form of a new group called the 'Ulster Unionist Assembly Party Group' whose membership was the 24 UUP MLAs and Mr Ervine. Sir Reg Empey justified the link by stating that under the d'Hondt method for allocating ministers in the Assembly, the new group would take a seat in the Executive from Sinn Féin, with their links to the IRA.

Following a request for a ruling from the DUP's Peter Robinson, the Speaker ruled that the UUPAG was not a political party within the meaning of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000.[10]

2007

The Ulster Unionist party did poorly in the Northern Ireland Assembly election, 2007. The party retained 18 of its seats within the assembly.[11] Sir Reg Empey was the only leader of one the four main parties not to be re-elected on first preference votes alone in the Assembly elections of March 2007.

| Party | Leader | Candidates | Seats | Change from 2003 |

1st Pref Votes | 1st Pref % | Change from 2003 |

Executive seats |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ulster Unionist | Reg Empey | 38 | 18 | −9 | 103,145 | 14.9 | −7.7 | 2 |

Structure

The UUP is still organised around the Ulster Unionist Council, which was from 1905 until 2004 the only legal representation of the party. Following the adoption of a new Constitution in 2004, the UUP has been an entity in its own right, however the UUC still exists as the supreme decision making body of the Party. In autumn 2007 the delegates system was done away with, and today all UUP members are members of the Ulster Unionist Council, with entitlements to vote for the Leader, party officers and on major policy decisions.

Each Constituency in Northern Ireland forms the boundary of a UUP Constituency Association, which is made up of branches formed along local boundaries (usually District Electoral Areas). There are also four 'representative bodies', the Ulster Womens Unionist Council, the Ulster Young Unionist Council, the Westminster Unionist Association (the party's Great Britain branch) and the Ulster Unionist Councillors Association. Each Constituency Association and Representative Body elects a number of delegates to the Party Executive Committee, which governs many areas of party administration such as membership and candidate selection.

The UUP maintained a formal connection with the Orange Order from its foundation until 2005, and with the Apprentice Boys of Derry until 1975. Only three of the party's Westminster MPs (Enoch Powell, Ken Maginnis and Sylvia Hermon) have not been members of the Orange Order. This was said to be a factor in discouraging Catholic membership of the party. While the party was considering structural reforms, including the connection with the Order, it was the Order itself that severed the connection in 2004. The connection with the Apprentice Boys was cut in a 1975 review of the party's structure as they had not taken up their delegates for several years beforehand.

Youth wing

The UUP's youth wing is the Ulster Young Unionist Council, first formed in 1949. Many of its members have stayed with the party, such as the present leader of the UUP. Others have left to start other Unionist parties. Having disbanded twice, in 1974 and 2004, the Council was re-constituted by young activists in March 2004. This resulted in the young unionists (YU) becoming a representative body of the UUP and subject to its revamp of their Constitution.

Policy summary

As a party reflecting the centrist ground of Unionist opinion, the broad policy outlook of the Ulster Unionist Party reflects the society in which it works and aims to develop and strengthen Northern Ireland's role as a partner within the United Kingdom. Under Sir Reg Empey's leadership, the party has stressed the need for social cohesion and a "Fair Society". It has stated it will make tackling poverty and homelessness a priority in any future Northern Ireland administration.

Constitutional affairs

- Constitutional monarchist

- Pro-devolution with a strong attachment to British parliamentary traditions

- Supports in principle the idea of power-sharing with democratic nationalist parties in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

- Seeks to promote and strengthen the constitutional union between Northern Ireland, England, Scotland, and Wales within the constitutional framework of the United Kingdom

- Seeks to develop friendly relations between all the peoples of the British Isles

- Supportive of a positive, co-operative relationship between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland

North/South and British/Irish relations

- The party has been supportive of constructive co-operation between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, since the latter renounced its territorial claim upon Northern Ireland as part of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

- Participated in North-South Ministerial Council (NSMC)

- Established British Irish Council

Justice and security

- Opposed the Patten Report (1999) and the subsequent changes to RUC

- Against 50:50 recruitment in the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI)

- Favours retention of full-time reserve to keep up police numbers

- Supports strong UK anti-terrorist legislation, identity cards, anti-social behaviour orders and a statutory Victims Charter for victims of crime

- Demands Assets Recovery Agency actions against both loyalist and republican paramilitaries

- Demands the abolition of Parades Commission, on the grounds that it restricts Freedom of Assembly.

Culture, social affairs and ethnic minorities

- UUP social policy places an emphasis on social cohesion, on the role of the family, and on the eradication of poverty and homelessness from Northern Ireland society.

- Under Sir Reg Empey's leadership, the party has stressed the need to help integrate ethnic minorities into Northern Irish life.

- The UUP supported the allocation of additional resources by the police to tackle Hate Crime against ethnic minorities.

- The party's website contains content in most of Northern Ireland's ethnic minority languages, including Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, Hindi, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi and Urdu.

- Established Ulster-Scots Agency

Agriculture

- The party has proposed a series of measures aimed at addressing the economic, social and environmental needs of rural communities. It has called for a Rural White Paper to bring together the various strands of government policy towards rural communities in the Province.

Education

- The party promotes a series of measures to reduce the "brain drain" of educated young Northern Ireland people to the mainland UK, Republic of Ireland and further afield.

Environment

- Proposes independent Environmental Protection Agency and Marine Act for coastal protection

- Supports reduced fossil fuel dependency and increased renewable energy use

- Aims to complete all Area of Special Scientific Interest designations by 2010

Health

- The party supports free personal care for the elderly and has stated it will make its implementation a priority in any future Northern Ireland administration.

Economic affairs

- Regionalist approach seeks maximum investment in Northern Ireland economy

Foreign affairs and Europe

- Supports the "War on Terrorism"

- Voted for the 2003 invasion of Iraq at Westminster

- Atlanticist

- Expresses support for involvement of Northern Ireland citizens in UK diplomacy and the United Nations

- Supports North Atlantic Treaty Organization alliance with the United Kingdom's allies

- General interest in international development issues

- Euro-sceptic centrist

- Opposes European Constitution

- Favours retention of the Pound Sterling, opposes UK entry into the Euro

Spokespersons

Party spokespersons as of July 2007[update] were:

| Policy Issue | |

|---|---|

| Social Development | Fred Cobain MLA

Cllr Michael Copeland |

| Agriculture and Rural Development | Tom Elliott MLA |

| Regional Development | Fred Cobain MLA |

| Education and Employment & Learning | Basil McCrea MLA |

| Finance and Personnel | Roy Beggs Jnr MLA |

| Environment | Sam Gardiner MLA |

| Health | Rev Robert Coulter MLA |

| Culture, Arts and Leisure | David McNarry MLA |

| Enterprise, Trade and Investment | Leslie Cree MLA |

| Tourism and consumer affairs | Alan McFarland MLA |

| Rights & Equality | Dermot Nesbitt |

| Finance and Personnel | Esmond Birnie |

| Children's issues | Roy Beggs Jnr MLA |

| Parading Issues | Fred Cobain MLA

Cllr Michael Copeland |

| Policing Issues | Fred Cobain MLA |

| Regional Development | Leslie Cree MLA |

| Victims' Issues | Derek Hussey |

Presidents

- 1905 James Hamilton

- 19?? James Craig

- 1969 Jack Andrews

- 1973? James G. Cunningham

- 1980 Sir George A. Clarke

- 1990 Sir Josias Cunningham

- 2000 Martin Smyth

- 2004 Lord Rogan

- 2006 Robert John White

General Secretaries

A list of General Secretaries of the Ulster Unionist Council.[12] From 1998 until 2007, the post was "Chief Executive of the Ulster Unionist Party".[13]

- 1905: T. H. Gibson

- 1906: Dawson Bates

- 1921: Wilson Hungerford

- 1941: Billy Douglas

- 1963: Jim Bailie

- 1974: Norman Hutton

- 1983: Frank Millar Jr

- 1987: Jim Wilson

- 1998: David Boyd

- 200?: Alastair Patterson

- 2004: Lyle Rea[13]

- 2005: Will Corry[13]

- 2007: Jim Wilson (acting)[14]

References

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Election 2005 | Northern Ireland | NI parties step on election trail

- ↑ Daily Telegraph | David Cameron launches biggest Conservative shake-up for decades

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Northern Ireland | What is the UVF?

- ↑ David Ervine | Politics | guardian.co.uk

- ↑ http://www.fas.org/irp/world/para/uvf.htm

- ↑ Feuding loyalists bring the fear back to Belfast - This Britain, UK - Independent.co.uk

- ↑ MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base

- ↑ BBC NEWS | UK | Northern Ireland | Row as Ervine joins UUP grouping

- ↑ BBC NEWS | UK | Northern Ireland | MP 'distressed' over Ervine move

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Northern Ireland | UUP-PUP link 'against the rules'

- ↑ DUP top in NI assembly election, BBC News Online, 12 March 2007

- ↑ Ulster Unionist Party: Party History

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "New chief exec for UUP", Belfast Telegraph, 3 April 2005

- ↑ Noel McAdam, "UUP veteran Wilson back to run the party", Belfast Telegraph, 30 March 2007

See also

- Category:Ulster Unionist Party politicians

- List of Northern Ireland Members of the House of Lords

- List of Ulster Unionist Party MPs

- Conservative Party

- Conservatives in Northern Ireland

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||