Ulster Defence Association

| Ulster Defence Association (UDA) |

|

|---|---|

| Participant in The Troubles | |

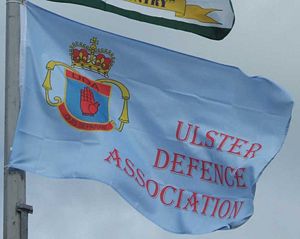

A UDA flag commonly flown in Loyalist areas of Northern Ireland. |

|

| Active | 1971-Present (officially ended armed campaign in 2007) |

| Leaders | Original Leadership Andy Tyrie, Ray Smallwoods Commander of the UFF John McMichael (until 1987)[1] UDA Inner Council Jackie McDonald, Johnny Adair, Jim Gray, Andre Shoukri, Billy McFarland, John Gregg, James 'Jimbo' Simpson[2] |

| Headquarters | Belfast |

| Area of operations |

Northern Ireland |

| Strength | ~40,000 (at peak) |

| Allies | LVF (from 1997),[3], RHD (until 2002)[4] |

| Opponents | PIRA, Irish Nationalists |

|

Irish Political History series |

|---|

Loyalism

|

|

Terminology

Key Documents

Parties

Paramilitaries

Other Organisations

Cultural

Songs

Symbols and Flags

Other movements

|

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is a loyalist paramilitary organization in Northern Ireland. Its main objective has been to reject unification of Ireland, seeking to do so through maintenance of the Act of Union. The UDA is outlawed as a proscribed terrorist group in the United Kingdom.[5]

Its militant branch has operated under the name Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). Its activities, which have included attacks against civilians as well as members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, were originally intended by the UDA as retaliatory acts for Irish Republican violence against Protestants in Northern Ireland. The UDA/UFF has also killed at least three Irish republican paramilitary members.[6][7]

The UDA officially ended its violent campaign in 2007 when it ordered its militant wing, the UFF, to stand down.[8]

Contents |

Origin and development

The Ulster Defence Association emerged in September 1971 as an umbrella organisation, from various vigilante groups commonly referred to as defence associations.[6] Its first leader was Charles Harding Smith, and its most prominent early spokesperson was Tommy Herron.[6] However Andy Tyrie would emerge as leader soon after.[9] At its peak of strength it held around forty thousand members, mostly part-time.[10][11] It also originally had the motto 'law before violence' and was in fact a legal organisation until it was banned on the 10th of August 1992.[6] During this period of legality, the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) committed a large number of paramilitary attacks,[12][13] including the assassination of Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) politician Paddy Wilson in 1973.[14]

In the 1970s the group favoured Northern Ireland independence, but they have retreated from this position.[15] The UDA was involved in the successful Ulster Workers Council Strike in 1974, which brought down the Sunningdale Agreement — an agreement which some loyalists and Unionists thought conceded too much to nationalist demands. The UDA enforced this general strike through widespread intimidation across Northern Ireland. The strike was led by Vanguard Assemblyman and UDA member, Glenn Barr.[16]

The UDA/UFF's official political position during the Troubles was that if the Provisional Irish Republican Army called off its campaign of violence, then the UDA would do the same. However, if the British government announced that it was withdrawing from Northern Ireland, then the UDA would act as "the IRA in reverse".[17]

In 1987, the deputy UDA's deputy commander John McMichael (who was then the leader of the UFF) promoted a document titled "Common Sense", which promoted a consensual end to the conflict in Northern Ireland, while maintaining the Union. The document advocated a power sharing assembly, involving both Nationalists and Unionists, an agreed constitution and new Bill of Rights. It is not clear however, whether this programme was adopted by the UDA as their official policy.[18] However McMichael's murder that same year and the subsequent removal of Tyrie from the leadership and his replacement with an Inner Council saw the UDA concentrate on stockpiling weapons rather than political ideas.[19]

The UDA and politics

The New Ulster Political Research Group (NUPRG) was initially the political wing of the UDA, founded in 1978, which then evolved into the Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party in 1981 under the leadership of John McMichael, a prominent UDA member killed by the IRA in 1987, amid suspicion that he was set up to be killed by some of his UDA colleagues. In 1989, the ULDP changed its name to the Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) and finally dissolved itself in 2001 following very limited electoral success. Gary McMichael, son of John McMichael, was the last leader of the UDP, which supported the signing of the Good Friday Agreement but had poor electoral success and internal difficulties. The Ulster Political Research Group (UPRG) was subsequently formed to give political analysis to the UDA and act as community workers in loyalist areas. It is currently represented on the Belfast City Council.

Campaign of violence and the UFF

Throughout its period of legality, the UDA's paramilitary operations were always carried out under the name UFF or Ulster Freedom Fighters. There is still debate over whether the two organisations were in fact one and the same, with the actions of Johnny Adair and his C Company unit often cited as evidence for the UFF's autonomy during the late 1980s and 1990s.[20] The UFF's campaign of violence began in 1970, under the leadership of the UDA's first commander Andy Tyrie, and continued into the 1980s. The peak of the UFF's armed campaign occurred in the early 1990s, the period when Johnny Adair's ruthless leadership of the Lower Shankill 2nd Battalion, C. Company resulted in a greater degree of tactical independence for the UFF.[21] They benefited, along with the Ulster Volunteer Force and a group called Ulster Resistance set up by the Democratic Unionist Party, from a shipment of arms imported from South Africa in 1988.[22] The weapons landed included rocket launchers, 200 rifles, 90 pistols and over 400 grenades.[18] Although almost two–thirds of these weapons were later recovered by the RUC, they enabled to UDA to launch an assassination campaign against their perceived enemies.

In 1992 Brian Nelson, a prominent UDA member convicted of sectarian murders, revealed that he was also a British Army agent. This led to allegations that the British Army and RUC were helping the UDA to target Irish republican activists. UDA members have since confirmed that they received intelligence files on republicans from British Army and RUC intelligence sources.[23]

One of the most notorious UDA attacks (carried out by the paramilitary wing, the UFF) came in October 1993, when two UFF men attacked a restaurant called the Rising Sun in the predominantly Catholic village of Greysteel, County Londonderry, where two hundred people were celebrating Halloween. The two men entered, shouted "Trick or treat!" and opened fire. Eight people were killed and nineteen wounded in what became known as the Greysteel massacre. The UDA/UFF claimed the attack was in retaliation to the IRA's Shankill Road bombing which killed nine, seven days earlier.

According to the Sutton database of deaths at the University of Ulster's CAIN project[24], the UDA/UFF was responsible for 259 killings during the Troubles. 208 of its victims were civilians (predominantly Catholics), 37 were other loyalist paramilitaries (including 30 of its own members), three were members of the security forces and eleven were republican paramilitaries. Some believe that a number of these attacks were carried out with the assistance or complicity of the British Army and/or the Royal Ulster Constabulary, which the Stevens Enquiry appeared to add credence to, although the exact number of people murdered as a result of collusion, if any, has not been revealed. The preferred modus operandi of the UDA was individual killings of select civilian targets in nationalist areas, rather than large-scale bomb or mortar attacks.

Leadership

The UDA operated a devolved structure of leadership, each with a brigadier representing one of the six brigade areas.[25] Currently, it is not entirely clear whether or not this structure has been maintained in the UDA's post cease-fire state. Some of the notable past brigadiers include:

Jackie McDonald - South Belfast (~1980s-Present)[26] Resident of the Taughmonagh estate in South Belfast.[27] McDonald was a cautious supporter of the UDA's ceasefire and a harsh critic of Johnny 'Mad Dog' Adair during his final years of membership of the organisation.[28] McDonald remains the only brigadier who did not have a commonly-used nickname.

Johnny 'Mad Dog' Adair - West Belfast (1990-2002)[29] An active figure in the UFF, Adair rose to notoriety in the early 1990s when he led the 2nd Battalion, C Company unit of the UFF in West Belfast which was responsible for one of the bloodiest killing sprees of the Troubles.[30]

Jim 'Doris Day' Gray - East Belfast (Unknown-2005)[31] An unlikely figure in Northern Ireland loyalism, the openly bi-sexual[32] Gray was a controversial figure in the organisation until his death on October 4, 2005. Always flamboyantly dressed, Gray was a key figure in the UDA's negotiations with Northern Ireland Secretary John Reid. It is widely believed that Gray received his nickname from the RUC Special Branch.[33]

Jimbo 'Bacardi Brigadier' Simpson - North Belfast (Unknown-2002)[34] Simpson is believed to have been an alcoholic, hence his nickname. He was leader of the UDA in the volatile North Belfast area, an interface between Catholics and Protestants in the New Lodge and Tiger's Bay neighbourhoods.[35]

Billy 'The Mexican' McFarland - North Antrim & Londonderry (Unknown-Unknown)[36]

Andre 'The Paki' Shoukri[37] - North Belfast (2002-2005)[38] Initially a close ally of Johnny Adair, Shoukri and his brother Ihab became involved with the UDA in his native North Belfast. The son of an Egyptian father and a Northern Irish mother, he was expelled from the UDA in 2005 following allegations of criminality.

Renunciation of violence

On November 11, 2007, the UDA formally renounced violence, but a commander said the group would not surrender its weapons to international disarmament officials.[39]

The UDA has been accused of taking vigilante action against alleged drug dealers, including tarring and feathering a man on the Taughmonagh estate in south Belfast.[40][41] The group had also developed strong links with neo-nazi groups such as Combat 18, though in 2005 the UDA announced that it was severing all ties with neo-Nazi organisations.

They have been involved in several feuds with the Ulster Volunteer Force, which led to many murders. The UDA has also been riddled by its own internecine warfare, with self-styled "brigadiers" and former figures of power and influence, such as Johnny Adair and Jim Gray (themselves bitter rivals), falling rapidly in and out of favour with the rest of the leadership. Gray and John Gregg are amongst those to have been killed during the internal strife. On February 22 2003, the UDA announced a "12-month period of military inactivity".[42] It said it will review its ceasefire every three months. It also apologised for the involvement of some of its members in the drugs trade. The UPRG's Frankie Gallagher has since taken a leading role in ending the association between the UDA and drug dealing.[43]

On June 20, 2006 the UDA expelled Andre Shoukri and his brother Ihab, two of its senior members who were heavily involved in crime. Some see this as a sign that the UDA is slowly coming away from crime.[44] The move did see the south-east Antrim brigade of the UDA, which had been at loggerheads with the leadership for some time, support Shoukri and break away under former UPRG spokesman Tommy Kirkham.[45] Other senior members met with Taoiseach Bertie Ahern for talks on the 13th of July in the same year.[46]

Although the group expressed a willingness to move from criminal activity to "community development," the IMC said it saw little evidence of this move because of the views of its members and the lack of coherence in the group's leadership as a result of a loose structure. While the report indicated the leadership intends to follow on its stated goals, factionalism hindered this change. Factionalism was, in fact, said to be the strongest hindrance to progress. The report also said the main non-splintered faction remained active, though it was considerably smaller than the resulting party. Individuals within the group, however, took their own initiative to criminal activity. Although loyalist actions were curtailed, most of the loyalist activity did come from the UDA. The IMC report concluded that the leadership's willingness to change has resulted in community tension and the group would continue to be monitored, although "the mainstream UDA still has some way to go." Furthermore, the IMC warned the group to "recognise that the organisation's time as a paramilitary group has passed and that decommissioning is inevitable." Decommissioning was said to be the "biggest outstanding issue for loyalist leaders, although not the only one."[47]

UDA - South East Antrim breakaway group

The breakaway faction continues to use the "UDA" title in it's name, although it too expressed willingness to move towards "community development." Though, yet again, serious crime is prevalent among the members, some of whom were arrested for drug peddling and extortion. Although a clear distinction was not available between the faction, as this was the twentieth IMC report was the first to differentiate the two, future reports would tackle the differences.[47]

Ceasefires

Its ceasefire was welcomed by the Northern Ireland Secretary of State, Paul Murphy and the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, Hugh Orde.

Following an August 2005 Sunday World article that poked fun at the gambling losses of one of its leaders, the UDA banned the sale of the newspaper from shops in areas it controls. Shops that defy the ban have suffered arson attacks, and at least one newsagent was threatened with death.[48] The PSNI have recently begun accompanying the paper's delivery vans.[49][50] The UDA was also considered to have played an instrumental role in loyalist riots in Belfast in September 2005.[51]

On the November 13, 2005, the UDA announced that it would "consider its future", in the wake of the standing down of the Provisional IRA and Loyalist Volunteer Force.[52]

In February 2006, the Independent Monitoring Commission reported UDA involvement in organised crime, drug trafficking, counterfeiting, extortion, money laundering and robbery.[53]

On 11th November 2007 the UDA announced that the Ulster Freedom Fighters would be stood down from midnight of the same day,[54] with its weapons "being put beyond use" although it stressed that these would not be decommissioned.

Red Hand Defenders and the LVF

The Red Hand Defenders is a cover name used by breakaway factions of the UFF and the LVF.[55] The term was originally coined in 1997 when members of the LVF carried out attacks on behalf of Johnny Adair's UFF 2nd Battalion, 'C' Company (Shankill Road) and vice-versa.[56] The relationship between the UFF (specifically Adair's unit, not the wider leadership of the UDA) was initially formed after the death of Billy Wright, the previous leader of the LVF, and Adair's personal friendship with Mark 'Swinger' Fulton, the organisations new chief.

The necessity for a cover name resulted from the need to avoid tensions between the UDA and the UVF, the organisation from which the LVF had broken away. It was perceived that any open co-operation between the UDA and the LVF would anger the UVF, something which proved to be the case in following years and resulted in the infamous 'Loyalist Feud'.[57] There has been debate as to whether or not the Red Hand Defenders have become an entity in their own right[58] made up of dissident factions from both the UDA and the LVF (both of which have now declared ceasefires whilst the RHD has not), though much intelligence has been based on the claims of responsibility which, as has been suggested,[59] are frequently misleading.

References

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/1762550.stm

- ↑ Home Office, Government of the United Kingdom - Proscribed Terrorist Groups. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 CAIN project

- ↑ Bloody Sunday victim did volunteer for us, says IRA The Guardian 19 May 2002

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/7089310.stm

- ↑ H. McDonald & J. Cusack, UDA – Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror, Dublin, Penguin Ireland, 2004, pp. 64-65

- ↑ The downfall of Mad Dog Adair, part 2 | Magazine | The Observer

- ↑ The Peace Process in Northern Ireland 2

- ↑ BBC News | UK | UFF involved in Ulster murders - police chief

- ↑ Ulster Defense Association

- ↑ The Guardian

- ↑ Ulster Defence Association

- ↑ Taylor, Peter (1999). Loyalists. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. pp. 128-131. ISBN 0-7475-4519-7.

- ↑ Brendan O'Brien, the Long War, the IRA and Sinn Féin (1995), p.91

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ibid.

- ↑ "UDA"

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ Table from CAIN showing deaths per year

- ↑ O'Brien p.92

- ↑ Peter Taylor Loyalists

- ↑ Conflict Archive on the Internet

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. pp. pp. 280-283. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. pp. pp. 280-283. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. pp. pp. 280-283. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ Lister, David (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Cox & Wyman. ISBN 978-1-84018-890-5.

- ↑ CBC News: Protestant paramilitary group in N. Ireland renounces violence

- ↑ Henry McDonald Terror gangs fight to keep street power, The Observer, 2 September 2007, accessed 13 January 2008

- ↑ Henry McDonald Law and order Belfast-style as two men are forced on a 'walk of shame', The Observer, 13 January 2008, accessed 13 January 2008

- ↑ Scotland on Sunday

- ↑ Loyalist Drug Dealers Are "Scum" Says UPRG

- ↑ BBC Report

- ↑ UDA expels south east Antrim brigade chiefs

- ↑ UTV report

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 http://www.independentmonitoringcommission.org/documents/uploads/Twentieth%20Report.pdf

- ↑ Press Gazette

- ↑ Times Online

- ↑ Nuzhound

- ↑ BBC

- ↑ RTE

- ↑ Eighth Report of the Independent Monitoring Commission

- ↑ BBC NEWS | UK | Northern Ireland | UFF given the order to stand down

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

- ↑ FAS

- ↑ David Lister and Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair

See also

- Ulster Young Militants

- Jackie McDonald

Further reading

- Steve Bruce, The Red Hand, 1992, ISBN 0-19-215961-5

- Colin Crawford, Inside the UDA: Volunteers and Violence, 2003.

- Ed Moloney, The Secret History of the IRA

- Brendan O'Brien, The Long war, the IRA and Sinn Féin