Ulster

| Ulster Ulaidh |

||

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

|

||

| Statistics | ||

| Area: | 24,481 km² | |

|

Population (2006 estimate) |

1,993,918 | |

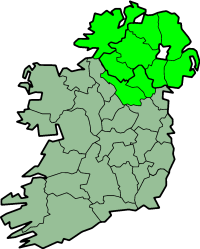

Ulster (Irish: Ulaidh, IPA: [ˈkwɪɟɪ ˈʌlˠu / ˈʌlˠi]) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, in addition to Connacht, Munster and Leinster. The name is often used as a synonym for Northern Ireland, one of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom[1] although Northern Ireland covers only two thirds of Ulster.

Ulster is traditionally composed of nine counties: three of which are part of the Republic of Ireland with the remaining six constituting Northern Ireland.

Contents |

Terminology

Its name derives from the Irish Cúige Uladh (pronounced "Kooi-gah UH-loo"), meaning "fifth of the Ulaidh", the ancient inhabitants of the region. The Irish Ulaidh with the addition of the Old Norse staðr (meaning "place" or "territory") yields "Ulaidh Staðr" or, in English, "Ulster."

Some sources refer to the inhabitants of Ulster as Ultonians – from the traditional Latin form of the name of the province, Ultonia. In the past however, the word Ullish has also been used as an adjective to describe people and things from Ulster. The words Ulsterman and Ulstermen are also used, and the Gaelic word for someone from Ulster is Ultach.

Many inhabitants (especially unionists) refer to the six-county Northern Ireland as "Ulster".

Geography and demographics

Ulster has a population of just under 2 million people and an area of 24,481 square kilometres (8,952 square miles). Its biggest city, Belfast has an urban area of over half a million inhabitants. Six of Ulster's nine counties, Antrim (Aontroim), Armagh (Ard Mhacha), Down (An Dún), Fermanagh (Fear Manach), Londonderry (Doire) (formerly known as County Coleraine before being renamed and expanded during the Plantation of Ulster) and Tyrone (Tír Eoghain), form Northern Ireland, and remained part of the United Kingdom after the partition of Ireland in 1921. Three Ulster counties, Cavan (An Cabhán), Donegal (Dún na nGall) and Monaghan (Muineachán) form part of the Republic of Ireland. About half of Ulster's population lives in Counties Antrim and Down. Across the nine counties, according to the aggregate UK 2001 Census and Irish 2002 Census, there is a very slim Catholic plurality over Protestant (49% against 48%), but not an overall majority (people of "no religion" or those "not stating" religion making up the balance).

The biggest lake in Ireland, and in the UK, Lough Neagh, lies in eastern Ulster. The province's highest point, Slieve Donard (848 metres), stands in County Down. The most northerly point of Ireland, Malin Head is in County Donegal as are the highest (601 metres) sea cliffs in Europe, at Slieve League. The longest river in Ireland, the Shannon, rises in County Cavan. Volcanic activity in eastern Ulster led to the formation of the Antrim Plateau and the Giant's Causeway, one of Ireland's three UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The geographical centre of Ulster lies between the villages of Pomeroy and Carrickmore in County Tyrone. In terms of area, County Donegal is the largest county in all of Ulster. The two largest cities in the province are Belfast and Derry. Belfast is Ireland's second largest city.

Ulster's main airport is Belfast International Airport (popularly called Aldergrove Airport), which is located at Aldergrove, near Antrim Town, in County Antrim. George Best Belfast City Airport (sometimes referred to as "the City Airport" or "the Harbour Airport") is the other, smaller airport in that city. It is located at Sydenham in East Belfast. The City of Derry Airport is located at Eglinton on the eastern outskirts of the city of Derry and is a major airport for the city and its district, West Tyrone and County Donegal.

| County | Population | Area |

|---|---|---|

| County Antrim | 616,384 | 2,844 km² |

| County Armagh | 126,803 | 1,254 km² |

| County Cavan | 56,546 | 1,931 km² |

| County Donegal | 137,575 | 4,841 km² |

| County Down | 410,487 | 2,448 km² |

| County Fermanagh | 54,033 | 1,691 km² |

| County Londonderry | 211,669 | 2,074 km² |

| County Monaghan | 52,593 | 1,294 km² |

| County Tyrone | 158,460 | 3,155 km² |

| Grand Total | 1,993,918 | 24,481 km² |

Cities and towns over 30,000

In order of size:

- Belfast (275,000)

- Derry (90,000)

- Bangor (80,000)

- Lisburn (70,000)

- Newtownabbey (60,000)

- Craigavon (60,000)

- Newry (40,000)

- Ballymena (30,000)

- Carrickfergus (30,000)

- Newtownards (30,000)

- Portadown (30,000)

Languages

Most people in Ulster speak English. Irish is the next most commonly spoken language; some 10% of people in Northern Ireland have "some knowledge of Irish", while the language is taught in all schools in the counties that are part of the Republic. In responses to the 2001 census in Northern Ireland 10% of the population claimed "some knowledge of Irish"[2], 4.7% to "speak, read, write and understand" Irish[2]. Large parts of County Donegal are Gaeltacht areas where Irish is the first language and some people in west Belfast also speak Irish, especially in the 'Gaeltacht Quarter'[3]. The dialect of Irish (Gaeilge) most commonly spoken in Ulster (especially throughout Northern Ireland and County Donegal) is Gaeilge Tír Chonaill or Donegal Irish, also known as Gaeilge Uladh or Ulster Irish. Donegal Irish has many similarities to Scottish Gaelic. Cantonese forms the third most common language, mostly due to the considerable Chinese community of Belfast, the province's largest city. Ulster Scots (a dialect of Scots which is also sometimes known as Ullans) is widely spoken in rural areas throughout Northern Ireland and the east of County Donegal.

Prehistory

The archaeology of Ulster gives examples of "ritual enclosures" such as the "Giant' Ring" near Belfast which is an earth bank about 590 feet in diameter and 15 feet high in the centre of which there is a dolmen (Riordain, 66).[4]

History and politics

Early history

- Further information: History of Ireland

Ulster is one of the four Irish provinces. Its name derives from the Irish language Cúige Uladh (pronounced "Kooi-gah UH-loo"), meaning "'fifth' of the Ulaidh", named for the ancient inhabitants of the region.

The province's early story extends further back than written records and survives mainly in legends such as the Ulster Cycle. In early medieval Ireland, the Uí Néill (O'Neill) dynasty dominated Ulster from their base in Tír Eóghain (Eoghan's Country) — most of which forms modern County Tyrone. The Ó Domhnaill (O'Donnell) dynasty were Ulster's second most powerful clan from the early thirteenth-century through to the beginning of the seventeenth-century. The O'Donnells ruled over Tír Chonaill (most of modern County Donegal) in West Ulster. After the Norman invasion of Ireland in the twelfth century, the east of the province fell by conquest to Norman barons, first De Courcy (died 1219), then Hugh de Lacy (1176-1243), who founded the Earldom of Ulster — based around the modern counties of Antrim and Down. However, by the end of the 15th century the Earldom had collapsed and Ulster had become the only Irish province completely outside of English control.

In the 1600s Ulster was the last redoubt of the traditional Gaelic way of life, and following the defeat of the Irish forces in the Nine Years War (1594-1603) at the battle of Kinsale (1601), Elizabeth I's English forces succeeded in subjugating Ulster and all of Ireland. The Gaelic leaders of Ulster, the O'Neills and O'Donnells, finding their power under English suzerainty limited, decamped en masse in 1607 (the Flight of the Earls) to Roman Catholic Europe. This allowed the English Crown to plant Ulster with more loyal English and Scottish planters, a process which began in earnest in 1610.

Plantations and civil wars

The Plantation of Ulster, run by the government, settled only the counties confiscated from those Irish families that had taken part in the Nine Years War. In general the "ordinary" native Irish remained in occupation of their land, they were neither removed nor Anglicised. [1] Counties Donegal, Tyrone, Armagh, Cavan, Londonderry and Fermanagh comprised the official plantation. However, the most extensive settlement in Ulster of English, Scots and Welsh — as well as Protestants from throughout the European continent — occurred in Antrim and Down. These counties, though not officially planted, had suffered de-populatation during the war and proved attractive to settlers from nearby Scotland. This unofficial settlement continued well into the 18th century, interrupted only by the Catholic uprising of 1641.

This rebellion initially led by Phelim O'Neill, was intended to seize power rapidly, but quickly degenerated into attacks on Protestant settlers. Dispossessed Catholics slaughtered thousands of Protestants, an event which remains strong in Ulster Protestant folk-memory. In the ensuing wars (1641–1653, fought against the background of civil war in England, Scotland and Ireland), Ulster became a battleground between the Protestant settlers and the native Irish Catholics. In 1646, the Irish Catholic army under Owen Roe O'Neill inflicted a bloody defeat on a Scottish Covenanter army at Benburb in County Tyrone, but the Catholic forces failed to follow up their victory and the war lapsed into stalemate. The war in Ulster ended with the defeat of the Irish Catholic army at the Battle of Scarrifholis on the western outskirts of Letterkenny, County Donegal, in 1650 and the occupation of the province by the Cromwellian New Model Army. The atrocities committed by all sides in the war poisoned the relationships between Ulster's ethno-religious communities for generations afterwards.

Forty years later, in 1688-1691, the former warring parties re-fought the conflict in the Williamite war in Ireland, when Irish Catholics ("Jacobites") supported James II (deposed in the Glorious Revolution) and Ulster Protestants (Williamites) backed William of Orange. At the start of the war, Irish Catholic Jacobites controlled all of Ireland for James, with the exception of the Protestant strongholds at Derry and at Enniskillen in Ulster. The Jacobites besieged Derry from December 1688 to July 1689, when a Williamite army from Britain relieved the city. The Protestant Williamite fighters based in Enniskillen defeated another Jacobite army at the battle of Newtownbutler on July 28, 1689. Thereafter, Ulster remained firmly under Williamite control and William's forces completed their conquest of the rest of Ireland in the next two years. Ulster Protestant irregulars known as "Enniskilleners" served with the Williamite forces. The war provided Protestant loyalists with the iconic victories of the Siege of Derry, the Battle of the Boyne (1 July 1690)and the Battle of Aughrim (12 July 1691), all of which their descendants still commemorate today. See also: Twelfth of July.

The Williamites' victory in this war ensured British and Protestant supremacy in Ireland for over 100 years. The Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland excluded most of Ulster's population from power on religious grounds. Roman Catholics (descended from the indigenous Irish) and Presbyterians (mainly descended from Scottish planters, but also from indigenous Irishmen who converted to Presbyterianism) both suffered discrimination under the Penal Laws, which gave full political rights only to Anglican Protestants (mostly descended from English settlers). In the 1690s, Scottish Presbyterians became a majority in Ulster, tens of thousands of them having emigrated there to escape a famine in Scotland.

Emigration

Considerable numbers of Ulster-Scots just a few generations after arriving in Ulster migrated to the North American colonies throughout the 18th century (250,000 settled in what would become the United States between 1717 and 1770 alone). According to Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (1988), Protestants were only one-third of the population of Ireland, but they comprised three-quarters of all emigrants from 1700 to 1776; 70% of these Protestants were Presbyterians.

Disdaining (or forced out of) the heavily English regions on the Atlantic coast, most groups of Ulster-Scots settlers crossed into the "western mountains", where their descendants populated the Appalachian regions and the Ohio Valley. Here they lived on the frontiers of America, carving their own world out of the wilderness. The Scotch-Irish soon became the dominant culture of the Appalachians from Pennsylvania to Georgia. Author (and U.S. Senator) Jim Webb puts forth a thesis in his book Born Fighting to suggest that the character traits he ascribes to the Scots-Irish such as loyalty to kin, mistrust of governmental authority, and a propensity to bear arms, helped shape the American identity.

In the United States Census, 2000, 4.3 million Americans claimed Scots-Irish ancestry, though James Webb suggests estimates that the true number of Scotch-Irish in the USA is more in the region of 27 million.[2] Interestingly, the areas where the most Americans reported themselves in the 2000 Census only as "American" with no further qualification (e.g. Kentucky, north-central Texas, and many other areas in the Southern US) are largely the areas where many Scots-Irish settled, and are in complementary distribution with the areas which most heavily report Scots-Irish ancestry.

Republicanism, rebellion, and communal strife

Most of the eighteenth century saw a calming of sectarian tensions in Ulster. The economy of the province improved, as small producers exported linen and other goods. Belfast developed from a village into a bustling provincial town. However, this did not stop many thousands of Ulster people from emigrating to British North America in this period, where they became known as "Scots Irish" or "Scotch-Irish".

Political tensions resurfaced, albeit in a new form, towards the end of the 18th century. In the 1790s many Catholics and Presbyterians, in opposition to Anglican domination and inspired by the American and French revolutions joined together in the United Irishmen movement. This group (founded in Belfast) dedicated itself to founding a non-sectarian and independent Irish republic. The United Irishmen had particular strength in Belfast, Antrim and Down. Paradoxically however, this period also saw much sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants, principally members of the Church of Ireland (Anglicans, who practised the state religion and had rights denied to both Presbyterians and Catholics), notably the "battle of the Diamond" in 1795, a faction fight between the rival "Defenders" (Catholic) and "Peep O'Day Boys" (Anglican), which led to over 100 deaths and to the founding of the Orange Order. This event, and many others like it, came about with the relaxation of the Penal Laws and as Catholics began to purchase land and involve themselves in the linen trade (activities which previously had involved many onerous restrictions). Protestants, including Presbyterians, who in some parts of the province had come to identify with the Catholic community, used violence to intimidate Catholics who tried to enter the linen trade. Estimates suggest that up to 7000 Catholics suffered expulsion from Ulster during this violence. Many of them settled in northern Connacht. These refugees' linguistic influence still survives in the dialects of Irish spoken in Mayo, which have many similarities to Ulster Irish not found elsewhere in Connacht. Loyalist militias, primarily Anglicans, also used violence against the United Irishmen and against Catholic and Protestant republicans throughout the province.

In 1798 the United Irishmen, led by Henry Joy McCracken, launched a rebellion in Ulster, mostly supported by Presbyterians. But the British authorities swiftly put down the insurgents and employed severe repression after the fighting had ended. In the wake of the failure of this rebellion, and following the gradual abolition of official religious discrimination after the Act of Union in 1800, Presbyterians came to identify more with the State and with their Anglican neighbours, who perceived them as the lesser of two evils.

Industrialisation, Home Rule, and partition

In the 19th century, Ulster became the most prosperous province in Ireland, with the only large-scale industrialisation in the country. In the latter part of the century, Belfast overtook Dublin as the largest city on the island. Belfast became famous in this period for its huge dockyards and shipbuilding — and notably for the construction of the RMS Titanic. In the 19th century, sectarian divisions in Ulster became hardened into the political categories of unionist (supporters of the Union with Britain; mostly, but not exclusively, Protestant) and nationalist (advocates of an Irish self-government; usually, though not exclusively, Catholic). The origins of Northern Ireland's current politics lie in these late 19th century disputes over Home Rule for Ireland, which Ulster Protestants usually opposed—fearing for their status in an autonomous Catholic-dominated Ireland and also not trusting politicians from the agrarian south and west to support the more industrial economy of Ulster.

To resist Home Rule, thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and James Craig, signed the "Ulster Covenant" of 1912, pledging to resist Home Rule. This movement also saw the setting up of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). In April 1914 30,000 German rifles with 3,000,000 rounds were landed at Larne, with the authorities blockaded by the UVF (see Larne gunrunning). The Curragh Incident showed it would be difficult to use the British army to coerce Ulster into home rule from Dublin.

In response, Irish nationalists created the Irish Volunteers, part of which later became the forerunner of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) — to seek to ensure the passing of the Home Rule Bill.

The outbreak of the Great War in 1914, in which thousands of Ulstermen and Irishmen of all religions and sects volunteered and died, interrupted this armed stand-off. In particular, the heavy casualties of the 36th (Ulster) Division (largely composed of volunteers from the UVF) became a source both of mourning and of pride for the loyalist community, and remains so to the present day.

In the aftermath of the War, Ireland saw several years of political violence, with Irish nationalists launching a guerrilla campaign against British rule as part of the Anglo-Irish War (January 1919–July 1921). In Ulster, the fighting generally took the form of street battles between Protestants and Catholics in the city of Belfast. Estimates suggest that about 600 civilians died in this communal violence, the majority of them (58%) Catholics. The IRA remained relatively quiescent in Ulster, with the exception of the south Armagh area, where Frank Aiken led it. A lot of IRA activity also took place at this time in County Donegal and the City of Derry, where one of the main Republican leaders was Peadar O'Donnell. Hugh O'Doherty, a Sinn Féin politician, was elected Mayor of Derry at this time. In the First Dáil, which was elected in late 1918, Prof. Eoin Mac Néill served as the Sinn Féin T.D. for Derry City.

Partition of Ireland, first mooted in 1912, was introduced with the enactment of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, which gave self-government to six of Ulster's north-eastern counties within the UK. This was confirmed by the Anglo-Irish Treaty (6 December 1921) which ended in the partition of Ireland between the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) and Northern Ireland. Hostilities formally ceased on July 11, 1921. Low-level violence, however, continued in Ulster, causing Michael Collins to order a boycott of Northern products in protest at attacks on the Catholic/Nationalist community. When the Irish Free State came into existence in 1922, the Northern Ireland Parliament (already in existence) was given the option to 'opt out', which it did. For the subsequent general history of Ulster see History of Northern Ireland and History of the Republic of Ireland.

Current politics

Electorally, voting in the six Northern Ireland counties of Ulster tends to follow religious or sectarian lines; noticeable religious demarcation does not exist in the South Ulster counties of Cavan and Monaghan in the Republic of Ireland. Some religious tensions remain in County Donegal (Ulster's largest county), especially in the Laggan Valley and Finn Valley in the east of that county. County Donegal is largely a Catholic county, but with a large Protestant minority. Generally, Protestants in Donegal vote for Fine Gael[5]. However, religious sectarianism in politics has largely disappeared from the rest of the Republic of Ireland. This was illustrated when Erskine H. Childers, a Church of Ireland member and Teachta Dála (TD, a member of the lower house of the National Parliament) who had represented Monaghan, won election as President after having served as a long-term minister under Fianna Fáil Taoisigh Éamon de Valera, Seán Lemass and Jack Lynch. Upon the Partition of Ireland in the very early 1920s, however, many Protestants from throughout the new Irish Free State (later called the Republic of Ireland) moved to Northern Ireland.

While the Protestant 'bloc vote' continues to exist in County Donegal, especially in the east of the county, where the Orange Order is relatively strong amongst the Protestant community, sectarian politics and sectarian feeling in County Donegal has begun to decline since the Good Friday Agreement (G.F.A.) in April 1998.

The Orange Order freely organises in counties Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan, with several Orange parades taking place throughout County Donegal each year. The largest Orange march in the Republic of Ireland takes place every July in the tiny village of Rossnowlagh, near Ballyshannon, in the very south of County Donegal. This march — like the other such marches in the county — takes place with the co-operation of An Garda Síochána (the national police force of the Republic) and a rather ambivalent local Catholic community. The Catholic community of Rossnowlagh is often commended for the dignified way in which it deals with this annual 'Orange invasion'. In the recent past, however, violence has erupted at Orange marches elsewhere in County Donegal, almost exclusively at such events in the east of the county, most notably in the town of Raphoe and in the village of St. Johnston (both in the Laggan Valley).

As of 2006[update], Northern Ireland has eight Catholic Members of Parliaments (of a total of 18 from the whole of Northern Ireland) in the British House of Commons at Westminster; and the other three counties have one Protestant T.D. of the ten it has elected to Dáil Éireann, the Lower House of the Oireachtas, the parliament of the Republic of Ireland. At present (August 2007) County Donegal sends six T.D.'s to Dáil Éireann. The county is divided into two constituencies: Donegal North-East and Donegal South-West, each with three T.D.'s. County Cavan and County Monaghan form the one constituency called Cavan-Monaghan, which sends four T.D.'s to the Dáil (one of whom is a Protestant). The Republic's parties have long ceased to base their selection of candidates purely on any religious criteria. For most of the twentieth century they chose at least one candidate from a Protestant background to attract the Protestant vote, but the disappearance of a bloc 'Protestant vote' (except in County Donegal) voting exclusively for a candidate on the basis of religion (with Protestant voters instead voting primarily for local candidates irrespective of religion) means that selection now depends largely on considerations of geography when electing TDs to Dáil Éireann under its Proportional Representation system. Again, County Donegal differs here in that a Protestant 'bloc vote' continues, especially in the east of the county.

The historic Flag of Ulster served as the basis for the Ulster Banner (often referred to as the Flag of Northern Ireland), which was the flag of the Government of Northern Ireland until the proroguing of the Stormont parliament in 1973.

Sport

In Gaelic games (which include Gaelic football and hurling), Ulster counties play the Ulster Senior Football Championship and Ulster Senior Hurling Championship. In football, the main competitions in which they compete with the other Irish counties are the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship and National Football League, while the Ulster club champions represent the province in the All-Ireland Senior Club Football Championship. Hurling teams play in the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, National Hurling League and All-Ireland Senior Club Hurling Championship. The whole province fields a team to play the other provinces in the Railway Cup in both football and hurling. Gaelic Football is by far the most popular of the GAA sports in Ulster but hurling is also played, especially in Antrim, Armagh, Derry, and Down.

The border has divided Association Football (soccer) teams since 1921[3]. The Irish Football Association oversees the sport in NI while the Football Association of Ireland oversees the sport in the Republic. As a result, separate international teams are fielded and separate championships take place (Irish Football League in Northern Ireland, League of Ireland in the rest of Ulster and Ireland). Anomalously, Derry City F.C. has played in the League of Ireland since 1985 due to crowd trouble at some of their Irish League matches prior to this. The other major Ulster team in the League of Ireland is Finn Harps of Ballybofey, County Donegal. There have been cup competitions between FAI and IFA clubs, most recently the Setanta Sports Cup.

In Rugby union, the Ulster branch of the Irish Rugby Football Union (I.R.F.U.) plays in the professional Magners League, formerly the Celtic League, along with teams from Wales, Scotland and the other Irish Provinces (Leinster, Munster and Connacht). Notable Ulster rugby players include Willy John McBride, Jack Kyle and Mike Gibson. The former is the most capped British and Irish Lion of all time, having completed four tours with the Lions in the sixties and seventies.

Cricket is also played in Ulster, especially in Northern Ireland and east Donegal. The game is mainly played and followed by members of the Protestant community[6].

References noted

- ↑ Ulster — Definitions from Dictionary.com

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency Census 2001 Output

- ↑ CAIN: Key Issue: Language: Pritchard, R.M.O. (2004) Protestants and the Irish Language: Historical Heritage and Current Attitudes in Northern Ireland

- ↑ Riordain, S.O. 1966 (reprint). Antiquities of the Irish Countryside. University Paperbacks, London. Methuen & Co Ltd

- ↑ "The Futre's Bright For Donegal's Orangemen". Independent News And Media (2004-7-11). Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ Explaining Northern Ireland: Broken Images

General references

The Ulster Countryside. Deane, C.Douglas. 1983. Century Books. ISBN 0 903152 17 7

Further reading

- Morton, O. 1994. Marine Algae of Northern Ireland. Ulster Museum, Belfast. ISBN 0900761 28 8

- Stewart and Corry's Flora of the North-east of Ireland. Third edition. Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast

See also

- Ulster nationalism

- Northern Ireland

- Kings of Ulster

- Provinces of Ireland

- Ulster-Scots (people)

- Ulster Scots language

- Mid Ulster English

- Ulster Irish

- Plantation of Ulster

- Plantations of Ireland

- Ulster Covenant

- Culture of Ulster

- Ulster GAA

- Ulster Rugby

External links

- BBC Nations History of Ireland

- Inconvenient Peripheries: Ethnic Identity and the United Kingdom EstatePDF (96.8 KiB) The cases of “Protestant Ulster” and Cornwall, by Professor Philip Payton

- Mercator Atlas of Europe Map of Ireland ("Irlandia") circa 1564

- Copeland Bird Observatory [4]

- Placenames Database of Ireland developed by Fiontar

|

||||||||||||||||||||