Ukraine

| Ukraine

Україна

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Ще не вмерла України ні слава, ні воля (Ukrainian) Shche ne vmerla Ukrayiny ni slava, ni volya (transliteration) Ukraine's glory has not yet perished, nor her freedom |

||||||

Location of Ukraine (orange)

on the European continent (white) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Kiev (Kyiv) |

|||||

| Official languages | Ukrainian | |||||

| Demonym | Ukrainian | |||||

| Government | Semi-presidential unitary state | |||||

| - | President | Viktor Yushchenko | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Yulia Tymoshenko | ||||

| - | Speaker of the Parliament | Volodymyr Lytvyn | ||||

| Independence | from the Soviet Union | |||||

| - | Declared | August 24, 1991 | ||||

| - | Referendum | December 1, 1991 | ||||

| - | Finalized | December 26, 1991 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 603,628 km2 (44th) 233,090 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 7% | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2008 estimate | 46,372,700[1] (27th) | ||||

| - | 2001 census | 48,457,102 | ||||

| - | Density | 77/km2 (115th) 199/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $321.874 billion[2] (29th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $6,968[2] (IMF) (83rd) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $141.644 billion[2] (45th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $3,066[2] (IMF) (88th) | ||||

| Gini (2006) | 31[3] | |||||

| HDI (2005) | ▲ 0.788 (medium) (76th) | |||||

| Currency | Hryvnia (UAH) |

|||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ua | |||||

| Calling code | 380 | |||||

Ukraine /juːˈkreɪn/ (Ukrainian: Україна, Ukrayina, [ukrɑˈjinɑ]) is a country in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the east, Belarus to the north, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary to the west, Romania, Moldova (including the breakaway Pridnestrovie) to the southwest, and the Black Sea and Sea of Azov to the south. The city of Kiev (Kyiv) is both the capital and the largest city of Ukraine.

The nation's modern history began with that of the East Slavs. From at least the 9th century, the territory of Ukraine was a center of the medieval Varangian-dominated East Slavic civilization, forming the state of Kievan Rus' which disintegrated in the 12th century. From the 14th century on, the territory of Ukraine was divided among a number of regional powers, and by the 19th century, the largest part of Ukraine was integrated into the Russian Empire, with the rest under Austro-Hungarian control. After a chaotic period of incessant warfare and several attempts at independence (1917–21) following World War I and the Russian Civil War, Ukraine emerged in 1922 as one of the founding republics of the Soviet Union. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic's territory was enlarged westward shortly before and after World War II, and again in 1954 with the Crimea transfer. In 1945, the Ukrainian SSR became one of the co-founding members of the United Nations.[4] Ukraine became independent again after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. This began a period of transition to a market economy, in which Ukraine was stricken with an eight year recession.[5] Since then, the economy has been experiencing a stable increase, with real GDP growth averaging eight percent annually.

Ukraine is a unitary state composed of 24 oblasts (provinces), one autonomous republic (Crimea), and two cities with special status: Kiev, its capital, and Sevastopol, which houses the Russian Black Sea Fleet under a leasing agreement. Ukraine is a republic under a semi-presidential system with separate legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Since the collapse of the USSR, Ukraine continues to maintain the second largest military in Europe, after that of Russia. The country is home to 46.4 million people, 77.8 percent of whom are ethnic Ukrainians, with sizable minorities of Russians, Belarusians and Romanians. The Ukrainian language is the only official language in Ukraine, while Russian is also widely spoken and is known to most Ukrainians as a second language. The dominant religion in the country is Eastern Orthodox Christianity, which has heavily influenced Ukrainian architecture, literature and music.

Contents |

History

Early history

Human settlement in the territory of Ukraine dates back to at least 4500 BC, when the Neolithic Cucuteni culture flourished in a wide area that covered parts of modern Ukraine including Trypillia and the entire Dnieper-Dniester region. During the Iron Age, the land was inhabited by Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians.[6] Between 700 BC and 200 BC it was part of the Scythian Kingdom, or Scythia. Later, colonies of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, and the Byzantine Empire, such as Tyras, Olbia, and Hermonassa, were founded, beginning in the 6th century BC, on the northeastern shore of the Black Sea, and thrived well into the 6th century AD. In the 7th century AD, the territory of eastern Ukraine was part of Old Great Bulgaria. At the end of the century, the majority of Bulgar tribes migrated in different directions and the land fell into the Khazars' hands.

Golden Age of Kiev

In the 9th century, much of modern-day Ukraine was populated by the Rus' people who formed the Kievan Rus'. Kievan Rus' included nearely all territory of modern Ukraine, Belarus, with larger part of it situated on the territory of modern Russia. During the 10th and 11th centuries, it became the largest and most powerful state in Europe.[3] In the following centuries, it laid the foundation for the national identity of Ukrainians and Russians.[7] Kiev, the capital of modern Ukraine, became the most important city of the Rus'. According to the Primary Chronicle, the Rus' elite initially consisted of Varangians from Scandinavia. The Varangians later became assimilated into the local Slavic population and became part of the Rus' first dynasty, the Rurik Dynasty.[7] Kievan Rus' was composed of several principalities ruled by the interrelated Rurikid Princes. The seat of Kiev, the most prestigious and influential of all principalities, became the subject of many rivalries among Rurikids as the most valuable prize in their quest for power.

The Golden Age of Kievan Rus' began with the reign of Vladimir the Great (Old East Slavic: Володимеръ Святославичь, Volodymyr, 980–1015), who turned Rus' toward Byzantine Christianity. During the reign of his son, Yaroslav the Wise (Russian: Ярослав Мудрый) (1019–1054), Kievan Rus' reached the zenith of its cultural development and military power.[7] This was followed by the state's increasing fragmentation as the relative importance of regional powers rose again. After a final resurgence under the rule of Vladimir Monomakh (1113–1125) and his son Mstislav (Russian: Мстислав Владимирович) (1125–1132), Kievan Rus' finally disintegrated into separate principalities following Mstislav's death.

In the 11th and 12th centuries, constant incursions by nomadic Turkic tribes from the uncultivated "wild steppe" (дике поле), such as the Pechenegs and the Kipchaks, caused a massive migration of Slavic populations to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north.[8] The 13th century Mongol invasion devastated Kievan Rus'. Kiev was totally destroyed in 1240.[9] On the Ukrainian territory, the state of Kievan Rus' was succeeded by the principalities of Galich (Halych) and Volodymyr-Volynskyi, which were merged into the state of Galicia-Volhynia.

Foreign domination

- See also: Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Crown of the Polish Kingdom, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and Russian Empire

In the mid-14th century, Galicia-Volhynia was subjugated by Casimir the Great of Poland, while the heartland of Rus', including Kiev, fell under the Gediminas of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania after the Battle on the Irpen' River. Following the 1386 Union of Krevo, a dynastic union between Poland and Lithuania, most of Ukraine's territory was controlled by the increasingly Ruthenized local Lithuanian nobles as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. At this time, the term Ruthenia and Ruthenians as the Latinized versions of "Rus'", became widely applied to the land and the people of Ukraine, respectively.[10]

By 1569, the Union of Lublin formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a significant part of Ukrainian territory was moved from largely Ruthenized Lithuanian rule to the Polish administration, as it was transferred to the Polish Crown. Under the cultural and political pressure of Polonisation much of the Ruthenian upper class converted to Catholicism and became indistinguishable from the Polish nobility.[11] Thus, the Ukrainian commoners, deprived of their native protectors among Ruthenian nobility, turned for protection to the Cossacks, who remained fiercely orthodox at all times and tended to turn to violence against those they perceived as enemies, particularly the Polish state and its representatives.[12] Ukraine suffered a series of Tatar invasions, the goal of which was to loot, pillage and capture slaves into jasyr.[13]

In the mid-17th century, a Cossack military quasi-state, the Zaporozhian Host, was established by the Dnieper Cossacks and the Ruthenian peasants fleeing Polish serfdom.[14] Poland had little real control of this land (Wild Fields), yet they found the Cossacks to be a useful fighting force against the Turks and Tatars, and at times the two allied in military campaigns.[15] However, the continued enserfment of peasantry by the Polish nobility emphasized by the Commonwealth's fierce exploitation of the workforce, and most importantly, the suppression of the Orthodox Church pushed the allegiances of Cossacks away from Poland.[15] Their aspiration was to have representation in Polish Sejm, recognition of Orthodox traditions and the gradual expansion of the Cossack Registry. These were all vehemently denied by the Polish nobility. The Cossacks eventually turned for protection to Orthodox Russia, a decision which would later lead towards the downfall of the Polish-Lithuanian state,[14] and the preservation of the Orthodox Church and in Ukraine.[16]

In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky led the largest of the Cossack uprisings against the Commonwealth and the Polish king John II Casimir.[17] Left-bank Ukraine was eventually integrated into Russia as the Cossack Hetmanate, following the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav and the ensuing Russo-Polish War. After the partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th century by Prussia, Habsburg Austria, and Russia, Western Ukrainian Galicia was taken over by Austria, while the rest of Ukraine was progressively incorporated into the Russian Empire. Despite the promises of Ukrainian autonomy given by the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the Ukrainian elite and the Cossacks never received the freedoms and the autonomy they were expecting from Imperial Russia. However, within the Empire, Ukrainians rose to the highest offices of Russian state, and the Russian Orthodox Church.[a] At a later period, the tsarist regime carried the policy of Russification of Ukrainian lands, suppressing the use of the Ukrainian language in print, and in public.[18]

World War I and revolution

- See also: Ukraine in World War I, Russian Civil War, and Ukraine after the Russian Revolution

Ukraine entered World War I on the side of both the Central Powers, under Austria, and the Triple Entente, under Russia. During the war, Austro-Hungarian authorities established the Ukrainian Legion to fight against the Russian Empire. This legion was the foundation of the Ukrainian Galician Army that fought against the Bolsheviks and Poles in the post World War I period (1919–23). Those suspected of the Russophile sentiments in Austria were treated harshly. Up to 5,000 supporters of the Russian Empire from Galicia were detained and placed in Austrian internment camps in Talerhof, Styria, and in a fortress at Terezín (now in the Czech Republic).[19]

With the collapse of the Russian and Austrian empires following World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917, a Ukrainian national movement for self-determination reemerged. During 1917–20, several separate Ukrainian states briefly emerged: the Ukrainian People's Republic, the Hetmanate, the Directorate and the pro-Bolshevik Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (or Soviet Ukraine) successively established territories in the former Russian Empire; while the West Ukrainian People's Republic emerged briefly in the former Austro-Hungarian territory. In the midst of Civil War, an anarchist movement called the Black Army led by Nestor Makhno also developed in Southern Ukraine.[20] However with Western Ukraine's defeat in the Polish-Ukrainian War followed by the failure of the further Polish offensive that was repelled by the Bolsheviks. According to the Peace of Riga concluded between the Soviets and Poland, western Ukraine was officially incorporated into Poland who in turn recognised the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in March 1919, that later became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or the Soviet Union in December, 1922.[21]

Interwar Soviet Ukraine

The revolution that brought the Soviet government to power devastated Ukraine. It left over 1.5 million people dead and hundreds of thousands homeless. The Soviet Ukraine had to face the famine of 1921.[22] Seeing the exhausted society, the Soviet government remained very flexible during the 1920s.[23] Thus, the Ukrainian culture and language enjoyed a revival, as Ukrainisation became a local implementation of the Soviet-wide Korenisation (literally indigenisation) policy.[21] The Bolsheviks were also committed to introducing universal health care, education and social-security benefits, as well as the right to work and housing.[24] Women's rights were greatly increased through new laws aimed to wipe away centuries-old inequalities.[25] Most of these policies were sharply reversed by the early-1930s after Joseph Stalin gradually consolidated power to become the de facto communist party leader and a dictator of the Soviet Union.

Starting from the late 1920s, Ukraine was involved in the Soviet industrialisation and the republic's industrial output quadrupled in the 1930s.[21] However, the industrialisation had a heavy cost for the peasantry, demographically a backbone of the Ukrainian nation. To satisfy the state's need for increased food supplies and to finance industrialisation, Stalin instituted a program of collectivisation of agriculture as the state combined the peasants' lands and animals into collective farms and enforcing the policies by the regular troops and secret police.[21] Those who resisted were arrested and deported and the increased production quotas were placed on the peasantry. The collectivisation had a devastating effect on agricultural productivity. As the members of the collective farms were not allowed to receive any grain until the unachievable quotas were met, starvation in the Soviet Union became widespread. In 1932–33, millions starved to death in a man-made famine known as Holodomor.[c] Scholars are divided as to whether this famine fits the definition of genocide, but the Ukrainian parliament and more than a dozen other countries recognise it as the genocide of the Ukrainian people.[c]

The times of industrialisation and Holodomor also coincided with the Soviet assault on the national political and cultural elite often accused in "nationalist deviations". Two waves of Stalinist political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union (1929–34 and 1936–38) resulted in the killing of some 681,692 people; this included four-fifths of the Ukrainian cultural elite and three quarters of all the Red Army's higher-ranking officers.[21][b]

World War II

- See also: Eastern Front (World War II)

Following the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland. Thus, Eastern Galicia and Volhynia with their Ukrainian population became reunited with the rest of Ukraine. The unification that Ukraine achieved for the first time in its history was a decisive event in the history of the nation.[26][27]

After France surrendered to Germany, Romania ceded Bessarabia and northern Bukovina to Soviet demands. The Ukrainian SSR incorporated northern and southern districts of Bessarabia, the northern Bukovina, and the Soviet-occupied Hertsa region. But it ceded the western part of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic to the newly created Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. All these territorial gains were internationally recognised by the Paris peace treaties of 1947.

German armies invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, thereby initiating four straight years of incessant total war. The Axis allies initially advanced against desperate but unsuccessful efforts of the Red Army. In the encirclement battle of Kiev, the city was acclaimed as a "Hero City", for the fierce resistance by the Red Army and by the local population. More than 600,000 Soviet soldiers (or one quarter of the Western Front) were killed or taken captive there.[28][29] Although the wide majority of Ukrainians fought alongside the Red Army and Soviet resistance,[30] some elements of the Ukrainian nationalist underground created an anti-Soviet nationalist formation in Galicia, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (1942) that at times engaged the Nazi forces; while another nationalist movement fought alongside the Nazis. In total, the number of ethnic Ukrainians that fought in the ranks of the Soviet Army is estimated from 4.5 million[30] to 7 million.[31][d] The pro-Soviet partisan guerrilla resistance in Ukraine is estimated to number at 47,800 from the start of occupation to 500,000 at its peak in 1944; with about 48 percent of them being ethnic Ukrainians.[32] Generally, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army's figures are very undependable, ranging anywhere from 15,000 to as much as 100,000 fighters.[33][34]

Initially, the Germans were even received as liberators by some western Ukrainians, who had only joined the Soviet Union in 1939. However, brutal German rule in the occupied territories eventually turned its supporters against the occupation. Nazi administrators of conquered Soviet territories made little attempt to exploit the population of Ukrainian territories' dissatisfaction with Stalinist political and economic policies.[35] Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, systematically carried out genocidal policies against Jews, deported others to work in Germany, and began a systematic depopulation of Ukraine to prepare it for German colonisation,[35] which included a food blockade on Kiev.

The vast majority of the fighting in World War II took place on the Eastern Front,[36] and Nazi Germany suffered 80 percent to 93 percent of all casualties there.[37] The total losses inflicted upon the Ukrainian population during the war are estimated between five and eight million,[38][39] including over half a million Jews killed by the Einsatzgruppen, sometimes with the help of local collaborators. Of the estimated 8.7 million Soviet troops who fell in battle against the Nazis,[40][41][42] 1.4 million were ethnic Ukrainians.[42][40][d][e] So to this day, Victory Day is celebrated as one of ten Ukrainian national holidays.[43]

Post-World War II

- See also: History of the Soviet Union (1953–1985) and History of the Soviet Union (1985–1991)

The republic was heavily damaged by the war, and it required significant efforts to recover. More than 700 cities and towns and 28,000 villages were destroyed.[44] The situation was worsened by a famine in 1946–47 caused by the drought and the infrastructure breakdown that took away tens of thousands of lives.[45]

The nationalist anti-Soviet resistance lasted for years after the war, chiefly in Western Ukraine, but also in other regions.[46] The Ukrainian Insurgent Army, continued to fight the USSR into the 1950s. Using guerilla war tactics, the insurgents targeted for assassination and terror those who they perceived as representing, or cooperating at any level with, the Soviet state.[47][48]

Following the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became the new leader of the USSR. Being the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukrainian SSR in 1938-49, Khrushchev was intimately familiar with the republic and after taking power union-wide, he began to emphasize the friendship between the Ukrainian and Russian nations. In 1954, the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav was widely celebrated, and in particular, Crimea was transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.[49]

Already by the 1950s, the republic fully surpassed pre-war levels of industry and production.[50] It also became an important center of the Soviet arms industry and high-tech research. Such an important role resulted in a major influence of the local elite. Many members of the Soviet leadership came from Ukraine, most notably Leonid Brezhnev, who would later oust Khrushchev and become the Soviet leader from 1964 to 1982, as well as many prominent Soviet sportspeople, scientists and artists.

On April 26, 1986, a reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded, resulting in the Chernobyl disaster, the worst nuclear reactor accident in history.[51][52] At the time of the accident seven million people lived in the contaminated territories, including 2.2 million in Ukraine.[53] After the accident, a new city, Slavutych, was built outside the exclusion zone to house and support the employees of the plant, which was decommissioned in 2000. Around 150,000 people were evacuated from the contaminated area, and 300,000–600,000 took part in the cleanup. By 2000, about 4,000 Ukrainian children had been diagnosed with thyroid cancer caused by radiation released by this incident.[54] Other Chernobyl disaster effects include other forms of cancer and genetic abnormalities, affecting newborns and children in particular.

Independence

On July 16, 1990, the new parliament adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine.[55] The declaration established the principles of the self-determination of the Ukrainian nation, its democracy, political and economic independence, and the priority of Ukrainian law on the Ukrainian territory over Soviet law. A month earlier, a similar declaration was adopted by the parliament of the Russian SFSR. This started a period of confrontation between the central Soviet, and new republican authorities. In August 1991, a conservative faction among the Communist leaders of the Soviet Union attempted a coup to remove Mikhail Gorbachev and to restore the Communist party's power. After the attempt failed, on August 24, 1991 the Ukrainian parliament adopted the Act of Independence in which the parliament declared Ukraine as an independent democratic state.[56] A referendum and the first presidential elections took place on December 1, 1991. That day, more than 90 percent of the Ukrainian people expressed their support for the Act of Independence, and they elected the chairman of the parliament, Leonid Kravchuk to serve as the first President of the country. At the meeting in Brest, Belarus on December 8, followed by Alma Ata meeting on December 21, the leaders of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, formally dissolved the Soviet Union and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).[57]

Ukraine was initially viewed as a republic with favorable economic conditions in comparison to the other regions of the Soviet Union.[58] However, the country experienced deeper economic slowdown than some of the other former Soviet Republics. During the recession, Ukraine lost 60 percent of its GDP from 1991 to 1999,[59][60] and suffered five-digit inflation rates.[61] Dissatisfied with the economic conditions, as well as crime and corruption, Ukrainians protested and organised strikes.[62]

The Ukrainian economy stabilized by the end of the 1990s. A new currency, the hryvnia, was introduced in 1996. Since 2000, the country has enjoyed steady economic growth averaging about seven percent annually.[63][5] A new Constitution of Ukraine was adopted in 1996, which turned Ukraine into a semi-presidential republic and established a stable political system. Kuchma was, however, criticized by opponents for concentrating too much of power in his office, corruption, transferring public property into hands of loyal oligarchs, discouraging free speech, and electoral fraud.[64] In 2004, Viktor Yanukovych, then Prime Minister, was declared the winner of the presidential elections, which had been largely rigged, as the Supreme Court of Ukraine later ruled.[65] The results caused a public outcry in support of the opposition candidate, Viktor Yushchenko, who challenged the results and led the peaceful Orange Revolution. The revolution brought Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko to power, while casting Viktor Yanukovych in opposition.[66]

Government and politics

- See also: Elections in Ukraine, Foreign relations of Ukraine, International membership of Ukraine, and Ukraine and the European Union

Ukraine is a republic under a mixed semi-parliamentary semi-presidential system with separate legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The President is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is the formal head of state.[67]

Ukraine's legislative branch includes the 450-seat unicameral parliament, the Verkhovna Rada.[68] The parliament is primarily responsible for the formation of the executive branch and the Cabinet of Ministers, which is headed by the Prime Minister.[69]

Laws, acts of the parliament and the cabinet, presidential decrees, and acts of the Crimean parliament may be abrogated by the Constitutional Court, should they be found to violate the Constitution of Ukraine. Other normative acts are subject to judicial review. The Supreme Court is the main body in the system of courts of general jurisdiction. Local self-government is officially guaranteed. Local councils and city mayors are popularly elected and exercise control over local budgets. The heads of regional and district administrations are appointed by the president.

Ukraine has a large number of political parties, many of which have tiny memberships and are unknown to the general public. Small parties often join in multi-party coalitions (electoral blocs) for the purpose of participating in parliamentary elections.

The European Union offered an Association Agreement with Ukraine in September, 2008. The country is a potential candidate for future enlargement of the European Union.

Military

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine inherited a 780,000 man military force on its territory, equipped with the third-largest nuclear weapon arsenal in the world.[70][71] In May 1992, Ukraine signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) in which the country agreed to give up all nuclear weapons to Russia for "disposal" and to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear weapon state. Ukraine ratified the treaty in 1994, and by 1996 the country became free of nuclear weapons.[70] Currently Ukraine's military is the second largest in Europe, after that of Russia.[72]

Ukraine also took consistent steps toward reduction of conventional weapons. It signed the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, which called for reduction of tanks, artillery, and armoured vehicles (army forces were reduced to 300,000). The country plans to convert the current conscript-based military into a professional volunteer military not later than in 2011.[73]

Ukraine has been playing an increasingly larger role in peacekeeping operations. Ukrainian troops are deployed in Kosovo as part of the Ukrainian-Polish Battalion.[74] A Ukrainian unit was deployed in Lebanon, as part of UN Interim Force enforcing the mandated ceasefire agreement. There was also a maintenance and training battalion deployed in Sierra Leone. In 2003–05, a Ukrainian unit was deployed in Iraq, as part of the Multinational force in Iraq under Polish command. The total Ukrainian military deployment around the world is 562 servicemen.[75]

Following independence, Ukraine declared itself a neutral state.[76] The country has had a limited military partnership with Russia, other CIS countries and a partnership with NATO since 1994. In the 2000s, the government was leaning towards the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, and a deeper cooperation with the alliance was set by the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan signed in 2002. It was later agreed that the question of joining NATO should be answered by a national referendum at some point in the future.[73]

Administrative divisions

The system of Ukrainian subdivisions reflects the country's status as a unitary state (as stated in the country's constitution) with unified legal and administrative regimes for each unit.

Ukraine is subdivided into twenty-four oblasts (provinces) and one autonomous republic (avtonomna respublika), Crimea. Additionally, the cities of Kiev, the capital, and Sevastopol, both have a special legal status. The 24 oblasts and Crimea are subdivided into 490 raions (districts), or second-level administrative units. The average area of a Ukrainian raion is 1,200 kilometres² (460 sq mi), the average population of a raion is 52,000 people.[77]

Urban areas (cities) can either be subordinated to the state (as in the case of Kiev and Sevastopol), the oblast or raion administrations, depending on their population and socio-economic importance. Lower administrative units include urban-type settlements, which are similar to rural communities, but are more urbanized, including industrial enterprises, educational facilities, and transport connections, and villages.

In total, Ukraine has 457 cities, 176 of them are labeled oblast-class, 279 smaller raion-class cities, and two special legal status cities. These are followed by 886 urban-type settlements and 28,552 villages.[77]

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

Geography

At 603,700 kilometers² (233,074 sq mi) and with a coastline of 2,782 kilometers (1,729 mi), Ukraine is the world's 44th-largest country (after the Central African Republic, before Madagascar). It is the second largest country in Europe (after the European part of Russia, before metropolitan France).[3]

The Ukrainian landscape consists mostly of fertile plains (or steppes) and plateaus, crossed by rivers such as the Dnieper (Dnipro), Seversky Donets, Dniester and the Southern Buh as they flow south into the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. To the southwest, the delta of the Danube forms the border with Romania. The country's only mountains are the Carpathian Mountains in the west, of which the highest is the Hora Hoverla at 2,061 m (6,762 ft), and those on the Crimean peninsula, in the extreme south along the coast.[78]

Ukraine has a mostly temperate continental climate, although a more Mediterranean climate is found on the southern Crimean coast. Precipitation is disproportionately distributed; it is highest in the west and north and lowest in the east and southeast. Western Ukraine, receives around 1,200 mm (47 in) of precipitation, annually. While Crimea, receives around 400 mm (15.4 in) of precipitation. Winters vary from cool along the Black Sea to cold farther inland. Average annual temperatures range from 5.5–7 °C (42–45 °F) in the north, to 11–13 °C (52–55.4 °F) in the south.[79]

Economy

In Soviet times, the economy of Ukraine was the second largest in the Soviet Union, being an important industrial and agricultural component of the country's planned economy.[3] With the collapse of the Soviet system, the country moved from a planned economy to a market economy. The transition process was difficult for the majority of the population which plunged into poverty. Ukraine's economy contracted severely following the years after the Soviet collapse. Day to day life for the average person living in Ukraine was a struggle. A significant number of citizens in rural Ukraine survived by growing their own food, often working two or more jobs and buying the basic necessities through the barter economy.[80]

In 1991, the government liberalized most prices to combat widespread product shortages, and was successful in overcoming the problem. At the same time, the government continued to subsidize government-owned industries and agriculture by uncovered monetary emission. The loose monetary policies of the early 1990s pushed inflation to hyperinflationary levels. For the year 1993, Ukraine holds the world record for inflation in one calendar year.[81] Those living on fixed incomes suffered the most.[21] Prices stabilized only after the introduction of new currency, the hryvnia, in 1996.

The country was also slow in implementing structural reforms. Following independence, the government formed a legal framework for privatisation. However, widespread resistance to reforms within the government and from a significant part of the population soon stalled the reform efforts. A large number of government-owned enterprises were exempt from the privatisation process. In the meantime, by 1999, the GDP had fallen to less than 40 percent of the 1991 level,[82] but recovered to slightly above the 100 percent mark by the end of 2006.[59]

Ukraine's 2007 GDP (PPP), as calculated by the IMF, is ranked 29th in the world and estimated at $399.866 billion.[59] Its GDP per capita in 2007 according to the IMF was 6968$ (in PPP terms), ranked 92th in the world.[59] Nominal GDP (in U.S. dollars, calculated at market exchange rate) was $140.5 billion, ranked 41st in the world.[3] By July 2008 the average nominal salary in Ukraine reached 1,930 hryvnias per month.[83] Despite remaining lower than in neighbouring central European countries, the salary income growth in 2008 stood at 36.8 percent[84] According to the UNDP in 2003 4.9 percent of the Ukrainian population lived under 2 US dollar a day[85] and 19.5 percent (UNDP figures) of the population lived below the national poverty line that same year.[86]

In the early 2000s, the economy showed strong export-based growth of 5 to 10 percent, with industrial production growing more than 10 percent per year.[87] Ukraine produces nearly all types of transportation vehicles and spacecraft. Antonov airplanes and KrAZ trucks are exported to many countries. The majority of Ukrainian exports are marketed to the European Union and CIS.[88] Since independence, Ukraine has maintained its own space agency, the National Space Agency of Ukraine (NSAU). The first astronaut of the NSAU to enter space under the Ukrainian flag was Leonid Kadenyuk on May 13, 1997. Ukraine became an active participant in scientific space exploration and remote sensing missions. Between 1991 and 2007, Ukraine has launched six self made satellites and 101 launch vehicles, and continues to design spacecraft.[89] So to this day, Ukraine is recognised as a world leader in producing missiles and missile related technology.[90][91]

The country imports most energy supplies, especially oil and natural gas, and to a large extent depends on Russia as its energy supplier. While 25 percent of the natural gas in Ukraine comes from internal sources, about 35 percent comes from Russia and the remaining 40 percent from Central Asia through transit routes that Russia controls. At the same time, 85 percent of the Russian gas is delivered to Western Europe through Ukraine.[92]

The World Bank classifies Ukraine as a middle-income state.[93] Significant issues include underdeveloped infrastructure and transportation, corruption and bureaucracy. In 2007 the Ukrainian stock market recorded the second highest growth in the world of 130 percent.[94] According to the CIA, in 2006 the market capitalisation of the Ukrainian stock market was $42.87 billion.[3] Growing sectors of the Ukrainian economy include the information technology (IT) market, which topped all other Central and Eastern European countries in 2007, growing some 40 percent.[95]

Ukraine was hit heavy by the economic crisis of 2008.[96]

Culture

- See also: Culture of Ukraine

Ukrainian customs are heavily influenced by Christianity, which is the dominant religion in the country.[97] Gender roles also tend to be more traditional, and grandparents play a greater role in raising children than in the West.[98] The culture of Ukraine has been also influenced by its eastern and western neighbours, which is reflected in its architecture, music and art.

The Communist era had quite a strong effect on the art and writing of Ukraine.[99] In 1932, Stalin made socialist realism state policy in the Soviet Union when he promulgated the decree "On the Reconstruction of Literary and Art Organisations". This greatly stifled creativity. During the 1980s glasnost (openness) was introduced and Soviet artists and writers again became free to express themselves as they wanted.[100]

The tradition of the Easter egg, known as pysanky, has long roots in Ukraine. These eggs were drawn on with wax to create a pattern; then, the dye was applied to give the eggs their pleasant colours, the dye did not affect the previously wax-coated parts of the egg. After the entire egg was dyed, the wax was removed leaving only the colourful pattern. This tradition is thousands of years old, and precedes the arrival of Christianity to Ukraine.[101] In the city of Kolomya near the foothills of the Carpathian mountains in 2000 was built the museum of Pysanka which won a nomination as the monument of modern Ukraine in 2007, part of the Seven Wonders of Ukraine action.

The traditional Ukrainian diet includes chicken, pork, beef, fish and mushrooms. Ukrainians also tend to eat a lot of potatoes, grains, fresh and pickled vegetables. Popular traditional dishes include varenyky (boiled dumplings with mushrooms, potatoes, sauerkraut, cottage cheese or cherries), borsch (soup made of beets, cabbage and mushrooms or meat) and holubtsy (stuffed cabbage rolls filled with rice, carrots and meat). Ukrainian specialties also include Chicken Kiev and Kiev Cake. Ukrainians drink stewed fruit, juices, milk, buttermilk (they make cottage cheese from this), mineral water, tea and coffee, beer, wine and horilka.[102]

Language

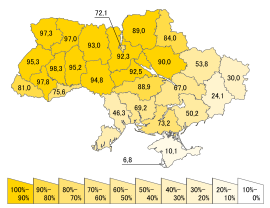

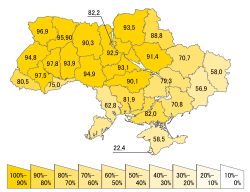

According to the Constitution, the state language of Ukraine is Ukrainian. Russian, which was the de facto official language of the Soviet Union, is widely spoken, especially in eastern and southern Ukraine. According to the 2001 census, 67.5 percent of the population declared Ukrainian as their native language and 29.6 percent declared Russian.[103] Most native Ukrainian speakers know Russian as a second language.

These details result in a significant difference across different survey results, as even a small restating of a question switches responses of a significant group of people.[f] Ukrainian is mainly spoken in western and central Ukraine. In western Ukraine, Ukrainian is also the dominant language in cities (such as Lviv). In central Ukraine, Ukrainian and Russian are both equally used in cities, with Russian being more common in Kiev,[f] while Ukrainian is the dominant language in rural communities. In eastern and southern Ukraine, Russian is primarily used in cities, and Surzhyk is used in rural areas.

For a large part of the Soviet era, the number of Ukrainian speakers was declining from generation to generation, and by the mid-1980s, the usage of the Ukrainian language in public life had decreased significantly.[104] Following independence, the government of Ukraine began following a policy of Ukrainisation,[105] to increase the use of Ukrainian, while discouraging Russian, which has been banned or restricted in the media and films.[106][107] This means that Russian-language programmes need a Ukrainian translation or subtitles, but this excludes Russian language media made during the Soviet era.

According to the Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Ukrainian is the only state language of the republic. However, the republic's constitution specifically recognises Russian as the language of the majority of its population and guarantees its usage 'in all spheres of public life'. Similarly, the Crimean Tatar language (the language of 12 percent of population of Crimea[108]) is guaranteed a special state protection as well as the 'languages of other ethnicities'. Russian speakers constitute an overwhelming majority of the Crimean population (77 percent), with Ukrainian speakers comprising just 10.1 percent, and Crimean Tatar speakers 11.4 percent.[109] But in everyday life the majority of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians in Crimea use Russian.[110]

Literature

- See also: Ukrainian literature

The history of Ukrainian literature dates back to the 11th century, following the Christianisation of the Kievan Rus’.[111] The writings of the time were mainly liturgical and were written in Old Church Slavonic. Historical accounts of the time were referred to as chronicles, the most significant of which was the Primary Chronicle.[112][g] Literary activity faced a sudden decline during the Mongol invasion of Rus'.[111]

Ukrainian literature again began to develop in the 14th century, and was advanced significantly in the 16th century with the introduction of print and with the beginning of the Cossack era, under both Russian and Polish dominance.[111] The Cossacks established an independent society and popularized a new kind of epic poems, which marked a high point of Ukrainian oral literature.[112] These advances were then set back in the 17th and early 18th centuries, when publishing in the Ukrainian language was outlawed and prohibited. Nonetheless, by the late 18th century modern literary Ukrainian finally emerged.[111]

The 19th century initiated a vernacular period in Ukraine, lead by Ivan Kotliarevsky’s work Eneyida, the first publication written in modern Ukrainian. By the 1830s, Ukrainian romanticism began to develop, and the nation’s most renowned cultural figure, romanticist poet-painter Taras Shevchenko emerged. Where Ivan Kotliarevsky is considered to be the ‘father’ of literature in the Ukrainian vernacular; Shevchenko is the father of a national revival.[113] Then, in 1863, use of the Ukrainian language in print was effectively prohibited by the Russian Empire.[18] This severely curtained literary activity in the area, and Ukrainian writers were forced to either publish their works in Russian or release them in Austrian controlled Galicia. The ban was never officially lifted, but it became obsolete after the revolution and the Bolsheviks’ coming to power.[112]

Ukrainian literature continued to flourish in the early Soviet years, when nearly all literary trends were approved. These policies faced a steep decline in the 1930s, when Stalin implemented his policy of socialist realism. The doctrine did not necessarily repress the Ukrainian language, but it required writers to follow a certain style in their works. Literary activities continued to be somewhat limited under the communist party, and it was not until Ukraine gained its independence in 1991 when writers were free the express themselves as they wished.[111]

Sport

- See also: Sport in Ukraine

Ukraine greatly benefited from the Soviet emphasis on physical education. Such policies left Ukraine with hundreds of stadia, swimming pools, gymnasia, and many other athletic facilities.[114] The most popular sport is football. The top professional league is the Vyscha Liha, also known as the Ukrainian Premier League. The two most successful teams in the Vyscha Liha are rivals FC Dynamo Kyiv and FC Shakhtar Donetsk. Although Shakhtar is the reigning champion of the Vyscha Liha, Dynamo Kyiv has been much more successful historically, winning two UEFA Cup Winners' Cups, one UEFA Super Cup, a record 13 USSR Championships and a record 12 Ukrainian Championships; while Shakhtar only won four Ukrainian championships.[115] Many Ukrainians also played for the Soviet national football team, most notably Igor Belanov and Oleg Blokhin, winners of the prestigious Golden Ball Award for the best football player of the year. This award was only presented to one Ukrainian after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Andriy Shevchenko, the current captain of the Ukrainian national football team. The national team made its debute in the 2006 FIFA World Cup, and reached the quarterfinals before losing to eventual champions, Italy. Ukrainians also fared well in boxing, where the brothers Vitali Klitschko and Wladimir Klitschko have held world heavyweight championships.

Ukraine made its Olympic debut at the 1994 Winter Olympics. So far, Ukraine has been much more successful in summer Olympics (96 medals in four appearances) than in the winter Olympics (five medals in four appearances). Ukraine is currently ranked 35th by number of gold medals won in the All-time Olympic Games medal count, with every country above them, except for Russia, having more appearances. The new step of Ukraine in the world sport is to host 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Ukrainian government bid Bukovel - the youngest Ukrainian ski resort[116] to be the host in 2018.The winning bid will be announced in 2011 at the 123rd IOC Session in Durban, South Africa.

Demographics

| Ethnic composition of Ukraine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 77.8% | |||

| Russians | 17.3% | |||

| Moldovans & Romanians | 0.8% | |||

| Belarusians | 0.6% | |||

| Crimean Tatars | 0.5% | |||

| Bulgarians | 0.4% | |||

| Hungarians | 0.3% | |||

| Poles | 0.3% | |||

| Jews | 0.2% | |||

| Armenians | 0.2% | |||

| Source: Ethnic composition of the population of Ukraine, 2001 Census | ||||

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, ethnic Ukrainians make up 77.8% of the population. Other significant ethnic groups are Russians (17.3%), Belarusians (0.6%), Moldovans (0.5%), Crimean Tatars (0.5%), Bulgarians (0.4%), Hungarians (0.3%), Romanians (0.3%), Poles (0.3%), Jews (0.2%), Armenians (0.2%), Greeks (0.2%) and Tatars (0.2%).[117] The industrial regions in the east and southeast are the most heavily populated, and about 67.2 percent of the population lives in urban areas.[118]

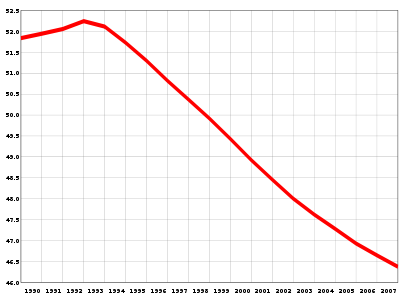

Ukraine is considered to be in a demographic crisis due to its high death rate and a low birth rate. The current Ukrainian birth rate is 9.55 births/1,000 population, and the death rate is 15.93 deaths/1,000 population. A factor contributing to the relatively high death is a high mortality rate among working-age males from preventable causes such as alcohol poisoning and smoking.[119] In 2007, the country's population was declining at the fourth fastest rate in the world.[120]

To help mitigate these trends, the government continues to increase child support payments. Thus it provides one-time payments of 12,250 Hryvnias for the first child, 25,000 Hryvnias for the second and 50,000 Hryvnias for the third and fourth, along with monthly payments of 154 Hryvnias per child.[84][121] The demographic trend is showing signs of improvement, as the birth rate has been steadily growing since 2001.[1] Net population growth over the first nine months of 2007 was registered in five provinces of the country (out of 24), and population shrinkage was showing signs of stabilising nationwide. The highest birth rates were in Western provinces.[122]

Significant migration took place in the first years of Ukrainian independence. More than one million people moved into Ukraine in 1991–2, mostly from the other former Soviet republics. In total, between 1991 and 2004, 2.2 million immigrated to Ukraine (among them, 2 million came from the other former Soviet Union states), and 2.5 million emigrated from Ukraine (among them, 1.9 million moved to other former Soviet Union republics).[123] Currently, immigrants constitute an estimated 14.7 percent of the total population, or 6.9 million people; this is the fourth largest figure in the world.[124]

| Rank | City | Division | Pop. | Rank | City | Division | Pop. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kiev | Kiev | 2,611,327 | 11 | Luhansk | Luhansk | 463,097 | |||

| 2 | Kharkiv | Kharkiv | 1,470,902 | 12 | Makiivka | Donetsk | 389,589 | |||

| 3 | Dnipropetrovsk | Dnipropetrovsk | 1,065,008 | 13 | Simferopol | Crimea | 358,108 | |||

| 4 | Odessa | Odessa | 1,029,049 | 14 | Vinnytsia | Vinnytsia | 356,665 | |||

| 5 | Donetsk | Donetsk | 1,016,194 | 15 | Sevastopol | Sevastopol | 342,451 | |||

| 6 | Zaporizhia | Zaporizhia | 815,256 | 16 | Kherson | Kherson | 328,360 | |||

| 7 | Lviv | Lviv | 732,818 | 17 | Poltava | Poltava | 317,998 | |||

| 8 | Kryvyi Rih | Dnipropetrovsk | 668,980[h] | 18 | Chernihiv | Chernihiv | 304,994 | |||

| 9 | Mykolaiv | Mykolaiv | 514,136 | 19 | Cherkasy | Cherkasy | 295,414 | |||

| 10 | Mariupol | Donetsk | 492,176 | 20 | Sumy | Sumy | 293,141 | |||

| 2001 Census[125] | ||||||||||

Religion

- See also: History of Christianity in Ukraine

The dominant religion in Ukraine is Eastern Orthodox Christianity, which is currently split between three Church bodies: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church autonomous church body under the Patriarch of Moscow, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church - Kiev Patriarchate, and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.[97]

A distant second by the number of the followers is the Eastern Rite Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which practices a similar liturgical and spiritual tradition as Eastern Orthodoxy, but is in communion with the Holy See (See of Rome) of the (Roman Catholic Church) and recognises the primacy of the Pope as head of the Church.[127]

Additionally, there are 863 Roman Catholic (Latin or Western Rite) communities, and 474 clergy members serving some one million Roman Catholics in Ukraine.[97] The group forms some 2.19 percent of the population and consists mainly of ethnic Poles and Hungarians, who live predominantly in the western regions of the country.

Protestant Christians also form around 2.19 percent of the population. Protestant numbers have grown greatly since Ukrainian independence. The Evangelical Baptist Union of Ukraine is the largest group, with more than 150,000 members and about 3000 clergy. The second largest Protestant church is the Ukrainian Church of Evangelical faith (Pentecostals) with 110000 members and over 1500 local churches and over 2000 clergy, but there also exist other Pentecostal groups and unions and together all Pentecostals are over 300,000, with over 3000 local churches. Also there are many Pentecostal high education schools such as the Lviv Theological Seminary and the Kiev Bible Institute. Other groups include Calvinists, Lutherans, Methodists and Seventh-day Adventists. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon Church) is also present.[97]

There are an estimated 500,000 Muslims in Ukraine, and about 300,000 of them are Crimean Tatars. There are 487 registered Muslim communities, 368 of them on the Crimean peninsula. In addition, some 50,000 Muslims live in Kiev; mostly foreign-born.[128]

The Jewish community is a tiny fraction of what it was before World War II. Jews form 0.63 percent of the population. A 2001 census indicated 103,600 Jews, although community leaders claimed that the population could be as large as 300,000. There are no statistics on what share of the Ukrainian Jews are observant, but Orthodox Judaism has the strongest presence in Ukraine. Smaller Reform and Conservative Jewish (Masorti) communities exist as well.[97]

As of January 1, 2006 there were 35 Krishna Consciousness and 53 Buddhist registered communities in the country.[128]

Education

- See also: Education in Ukraine and List of universities in Ukraine

According to the Ukrainian constitution, access to free education is granted to all citizens. Complete general secondary education is compulsory in the state schools which constitute the overwhelming majority. Free higher education in state and communal educational establishments is provided on a competitive basis.[129] There is also a small number of accredited private secondary and higher education institutions.

Due to the Soviet Union's emphasis on total access of education for all citizens, which continues today, the literacy rate is an estimated 99.4 percent.[3] Since 2005, an eleven-year school program has been replaced with a twelve-year one: primary education takes four years to complete (starting at age six), middle education (secondary) takes five years to complete; upper secondary then takes three years.[130] In the 12th grade, students take Government Tests, which are also referred to as school-leaving exams. These tests are later used for university admissions.

The Ukrainian higher education system comprises higher educational establishments, scientific and methodological facilities under federal, municipal and self-governing bodies in charge of education.[131] The organisation of higher education in Ukraine is built up in accordance with the structure of education of the world's higher developed countries, as is defined by UNESCO and the UN.[132]

Infrastructure

- See also: Transport in Ukraine

Most of the Ukrainian road system has not been upgraded since the Soviet era, and is now outdated. But the Ukrainian government has pledged to build some 4,500 km (2,800 mi) of motorways by 2012.[133] In total, Ukrainian paved roads stretch for 164,732 kilometres (102,401 mi).[3] Rail transport in Ukraine plays the role of connecting all major urban areas, port facilities and industrial centers with neighbouring countries. The heaviest concentration of railroad track is located in the Donbas region of Ukraine. Although the amount of freight transported by rail fell by 7.4 percent in 1995 in comparison with 1994, Ukraine is still one of the world's highest rail users.[134] The total amount of railroad track in Ukraine extends for 22,473 kilometres (13 970 mi), of which 9,250 kilometres (5750 mi) is electrified.[3]

Ukraine is one of Europe’s largest energy consumers, it consumes almost double the energy of Germany, per unit of GDP.[135] A great share of energy supply in Ukraine comes from nuclear power, with the country receiving most of its nuclear fuel from Russia. The remaining oil and gas, is also imported from the former Soviet Union. Ukraine is heavily dependent on its nuclear energy. The largest nuclear power plant in Europe, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, is located in Ukraine. In 2006, the government planned to build 11 new reactors by the year 2030, in effect, almost doubling the current amount of nuclear power capacity.[136] Ukraine's power sector is the twelfth-largest in the world in terms of installed capacity, with 54 gigawatts (GW).[135] Renewable energy still plays a very modest role in electrical output, and in 2005 energy production was met by the following sources: nuclear (47 percent), thermal (45 percent), hydro and other (8 percent).[136]

See also

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Population" (in Ukrainian). State statistics Committee of Ukraine (2008). Retrieved on 2008-07-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "Ukraine". CIA World Factbook (December 13, 2007). Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "List of Member States". United Nations. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Macroeconomic Indicators". National Bank of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Kievan Rus". The Columbia Encyclopedia. (2001–2005). Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ Klyuchevsky, Vasily. The course of the Russian history. v.1. ISBN 5-244-00072-1. http://www.kulichki.com/inkwell/text/special/history/kluch/kluch16.htm.

- ↑ "The Destruction of Kiev". University of Toronto's Research Repository. Retrieved on 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 69

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 92–93

- ↑ "Poland". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Historical survey > Slave societies

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Krupnytsky B. and Zhukovsky A.. "Zaporizhia, The". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Ukraine - The Cossacks". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Magocsi, p. 195

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 123–124

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Remy, Johannes (March-June 2007). "Valuev Circular and Censorship of Ukrainian Publications in the Russian Empire (1863-1876)". Canadian Slavonic Papers. findarticles.com. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Horbal, Bogdan. "Talerhof". The world academy of Rusyn culture. Retrieved on 2008-01-20.

- ↑ Cipko, Serge. "Makhno, Nestor". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-01-17.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 "Interwar Soviet Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Famine, Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 380

- ↑ "Communism". MSN Encarta. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ Cliff, p. 138–39

- ↑ Wilson, p. 17

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 487

- ↑ Roberts, p. 102

- ↑ Boshyk, p. 89

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "World wars". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "Losses of the Ukrainian Nation, p. 2" (in Ukrainian). Peremoga.gov.ua. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Subtelny, p. 476

- ↑ Magocsi, p. 635

- ↑ "Ukrainian Insurgent Army". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-20.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Ukraine - World War II and its aftermath". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 264

- ↑ Rozhnov, Konstantin, Who won World War II?. BBC. Citing Russian historian Valentin Falin. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Losses of the Ukrainian Nation, p. 1" (in Ukrainian). Peremoga.gov.ua. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Kulchytsky, Stalislav, "Demographic losses in Ukrainian in the twentieth century", Zerkalo Nedeli, October 2-8, 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Losses of the Ukrainian Nation, p. 7" (in Ukrainian). Peremoga.gov.ua. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Overy, p. 518

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Кривошеев Г. Ф., Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: потери вооруженных сил. Статистическое исследование (Krivosheev G. F., Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century: losses of the Armed Forces. A Statistical Study) (Russian)

- ↑ "Holidays". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-08-24.

- ↑ "Ukraine :: World War II and its aftermath". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Kulchytsky, Stanislav, "Demographic losses in Ukraine in the twentieth century", October October 2-8 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- ↑ Klymonchuk, Oksana, Archive data: OUN-UPA fought in Donbass region up to mid-50ies, Ukrainian Independent Information Agency (UNIAN), 18.03.2008. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ Piotrowski p. 352–54

- ↑ Weiner p.127–237

- ↑ "The Transfer of Crimea to Ukraine". International Committee for Crimea (July 2005). Retrieved on 2007-03-25.

- ↑ "Ukraine - The last years of Stalin's rule". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Serrill, Michael S. (September 1, 1986). "Anatomy of a catastrophe", TIME Magazine. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Remy, Johannes (1996). "'Sombre anniversary' of worst nuclear disaster in history - Chernobyl: 10th anniversary". UN Chronicle. findarticles.com. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ "Geographical location and extent of radioactive contamination". Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. (quoting the "Committee on the Problems of the Consequences of the Catastrophe at the Chernobyl NPP: 15 Years after Chernobyl Disaster", Minsk, 2001, p. 5/6 ff., and the "Chernobyl Interinform Agency, Kiev und", and "Chernobyl Committee: MailTable of official data on the reactor accident") Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ "Thyroid Cancer Effects in Children". International Atomic Energy Agency (August 2005). Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ "Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (July 16, 1990). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ "Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Resolution On Declaration of Independence of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (August 24, 1991). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ "Soviet Leaders Recall 'Inevitable' Breakup Of Soviet Union", RadioFreeEurope (December 8, 2006). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Shen, p. 41

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 "Ukrainian GDP (PPP)". World Economic Outlook Database, October 2007. International Monetary Fund (IMF). Retrieved on 2008-03-10.

- ↑ "Can Ukraine Avert a Financial Meltdown?". World Bank (June 1998). Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Figliuoli, Lorenzo; Lissovolik, Bogdan (August 31, 2002). "The IMF and Ukraine: What Really Happened". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Aslund, Anders (Autumn 1995). "Eurasia Letter: Ukraine's Turnaround". Foreign Policy (JSTOR) (100): 125–143. doi:. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0015-7228(199523)100%3C125%3AELUT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ "Ukraine. Country profile" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Wines, Michael (April 1, 2002). "Leader's Party Seems to Slip In Ukraine", The New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "The Supreme Court findings" (in Ukrainian). Supreme Court of Ukraine (December 3, 2004). Retrieved on 2008-07-07.

- ↑ "Ukraine-Independent Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2008-01-14.

- ↑ "General Articles about Ukraine". Government Portal. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Official Web-site. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Constitution of Ukraine". Wikisource. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "The history of the Armed Forces of Ukraine". The Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Ukraine Special Weapons". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Ukraine". MSN encarta. Retrieved on 2008-02-12.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "White Book 2006" (PDF). Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Multinational Peacekeeping Forces in Kosovo, KFOR". Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Peacekeeping". Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ↑ "Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Official Web-site. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Regions of Ukraine and their divisions" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Official Web-site. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Ukraine - Relief". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-12-27.

- ↑ "Ukraine - Climate". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-12-27.

- ↑ "Independent Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Skolotiany, Yuriy, The past and the future of Ukrainian national currency, Interview with Anatoliy Halchynsky, Mirror Weekly, #33(612), 2—September 8, 2006. Retrieved on 2008-07-05

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook - Ukraine. 2002 edition". CIA. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Average Wage Income in 2008 by Region". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 "Bohdan Danylyshyn at the Economic ministry". Economic Ministry. Retrieved on 2008-02-01.

- ↑ Data refer to the most recent year available during 1990-2005. Human and income poverty: developing countries / Population living below $2 a day (%), Human Development Report 2007/08, UNDP, accessed on February 3 2008

- ↑ Data refer to the most recent year available during 1990-2004. Human and income poverty: developing countries / Population living below the national poverty line (%), Human Development Report 2007/08, UNDP, accessed on February 3 2008.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook - Ukraine. 2004 edition". CIA. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.. .

- ↑ "Structure export and import, 2006". State statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Statistics of Launches of Ukrainian LV". National Space Agency of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Missle defence, NATO: Ukraine's tough call". Business Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Ukraine Special Weapons". The Nuclear Information Project. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Ukraine's gas sector" (.pdf) p.36 of 123. Oxford institute for energy studies. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "What are Middle-Income Countries?". The World Bank - (IEG). Retrieved on 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Pogarska, Olga. "Ukraine macroeconomic situation - Feb 2008", UNIAN news agency. Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ↑ Ballmer, Steve (May 20, 2008). "Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer Visits Ukraine". Microsoft. Retrieved on 2008-07-28.

- ↑ Ukraine’s November industrial output falls 28.6%, UNIAN (12-12-2008)

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 97.3 97.4 "State Department of Ukraine on Religious". 2003 Statistical report. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ "Cultural differences". Ukraine's Culture. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ "Interwar Soviet Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-12. "In all, some four-fifths of the Ukrainian cultural elite was repressed or perished in the course of the 1930s"

- ↑ "Gorbachev, Mikhail". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2008-07-30. "Under his new policy of glasnost (“openness”), a major cultural thaw took place: freedoms of expression and of information were significantly expanded; the press and broadcasting were allowed unprecedented candour in their reportage and criticism; and the country's legacy of Stalinist totalitarian rule was eventually completely repudiated by the government"

- ↑ "Pysanky - Ukrainian Easter Eggs". University of North Carolina. Retrieved on 2008-07-28.

- ↑ Stechishin, Savella. "Traditional Foods". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-08-10.

- ↑ "Linguistic composition of the population". All-Ukrainian population census, 2001. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ Shamshur, p. 159-168

- ↑ "Світова преса про вибори в Україні-2004 (Ukrainian Elections-2004 as mirrored in the World Press)". Архіви України (National Archives of Ukraine). Retrieved on 2008-01-07.

- ↑ "Anger at Ukraine's ban on Russian", BBC (April 15, 2004). Retrieved on 2008-07-07.

- ↑ "Wanted: Russian-language movies in Ukraine", RussiaToday (July 6, 2008). Retrieved on 2008-07-07.

- ↑ National structure of the population of Autonomous Republic of Crimea, 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ Linguistic composition of population Autonomous Republic of Crimea, 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ For a more comprehensive account of language politics in Crimea, see Natalya Belitser, "The Constitutional Process in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in the Context of Interethnic Relations and Conflict Settlement," International Committee for Crimea. Retrieved August 12, 2007.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 111.4 "Ukraine - Cultual Life - Literature". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 112.2 "Ukraine - Literature". MSN Encarta. Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ Struk, Danylo Husar. "Literature". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-01-17.

- ↑ "Ukraine - Sports and recreation". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Retrieved on 2008-01-12.

- ↑ Trophies of Dynamo - Official website of Dynamo Kyiv (Ukrainian), Accessed 23-6-08

- ↑ "Ukrainian ski resorts". Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- ↑ "Ethnical composition of the population of Ukraine". 2001 Census. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Ukraine - Statistics". United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Retrieved on 2008-01-07.

- ↑ "What Went Wrong with Foreign Advice in Ukraine?". The World Bank Group. Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ "Field Listing - Population growth rate". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "President meets with business bosses". Press office of President Victor Yushchenko. Retrieved on 2008-02-01.

- ↑ Ukraine’s birth rate shows first positive signs in decade Ukrainian Independent Information Agency (UNIAN). 05.10.2007 Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ Malynovska, Olena, Caught Between East and West, Ukraine Struggles with Its Migration Policy, National Institute for International Security Problems, Kiev, January 2006. Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ "International migration 2006". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved on 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Ukrainian census of 2001". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ "Kiev Saint Sophia Cathedral". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). UN. Retrieved on 2008-07-08.

- ↑ "Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC)". Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 "International Religious Freedom Report 2007 - Ukraine". United States Department of State (USDOS). Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

- ↑ Constitution of Ukraine Chapter 2, Article 53. Adopted at the Fifth Session of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine on June 28, 1996. Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ "General secondary education". Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-23.

- ↑ "System of Higher Education of Ukraine". Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-23.

- ↑ "System of the Education of Ukraine". Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. Retrieved on 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Bose, Mihir (July 7, 2008). "The long road to Kiev", BBC. Retrieved on 2008-07-29.

- ↑ "Transportation in Ukraine". U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved on 2007-12-22.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Ukraine". Energy Information Administration (EIA). US government. Retrieved on 2007-12-22.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "Nuclear Power in Ukraine". World Nuclear Association. Retrieved on 2007-12-22.

Notes

a.^ Among the Ukrainians that rose to the highest offices in the Russian Empire were Aleksey Razumovsky, Alexander Bezborodko, Ivan Paskevich. Among the Ukrainians who greatly influenced the Russian Orthodox Church in this period were Stephen Yavorsky, Feofan Prokopovich, Dimitry of Rostov.

b.^ See the Great Purge article for details.

c.1 2 Estimates on the number of deaths vary. Official Soviet data is not available because the Soviet government denied the existence of the famine. See the Holodomor article for details. Sources differ on interpreting various statements from different branches of different governments as to whether they amount to the official recognition of the Famine as Genocide by the country. For example, after the statement issued by the Latvian Sejm on March 13, 2008, the total number of countries is given as 19 (according to Ukrainian BBC: "Латвія визнала Голодомор ґеноцидом"), 16 (according to Korrespondent, Russian edition: "После продолжительных дебатов Сейм Латвии признал Голодомор геноцидом украинцев"), "more than 10" (according to Korrespondent, Ukrainian edition: "Латвія визнала Голодомор 1932-33 рр. геноцидом українців") Retrieved on 2008-01-27.

d.1 2 These figures are likely to be much higher, as they do not include Ukrainians from nations or Ukrainian Jews, but instead only ethnic Ukrainians, from the Ukrainian SSR.

e.^ This figure excludes POW deaths.

f.1 2 3 According to the official 2001 census data (by nationality; by language) about 75 percent of Kiev's population responded 'Ukrainian' to the native language (ridna mova) census question, and roughly 25 percent responded 'Russian'. On the other hand, when the question 'What language do you use in everyday life?' was asked in the 2003 sociological survey, the Kievans' answers were distributed as follows: 'mostly Russian': 52 percent, 'both Russian and Ukrainian in equal measure': 32 percent, 'mostly Ukrainian': 14 percent, 'exclusively Ukrainian': 4.3 percent.

"What language is spoken in Ukraine?", Welcome to Ukraine (2003/2). Retrieved on 2008-07-11.

g.^ Such writings were also the base for Russian and Belarusian literature.

h.^ Without the city of Inhulets.

Print sources

|

|

External links

- The President of Ukraine

- Government Portal of Ukraine

- The Parliament of Ukraine

- Wikimedia Atlas of Ukraine

- Wikia has a wiki on this subject at Ukraine

- Ukraine travel guide from Wikitravel

- Ukraine entry at The World Factbook

- Ukraine at the Open Directory Project

|

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||