Ukrainian language

| Ukrainian українська мова ukrayins'ka mova |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | [ukrɑˈjinʲsʲkɑ ˈmɔʋɑ] | |

| Spoken in: | See article | |

| Total speakers: | approximately 42[1][2] up to 47[3] mln | |

| Ranking: | 26 | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic East Slavic Ukrainian |

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | ||

| Regulated by: | National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | uk | |

| ISO 639-2: | ukr | |

| ISO 639-3: | ukr | |

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Ukrainian (in Ukrainian: украї́нська мо́ва, ukrayins'ka mova, [ukrɑˈjinʲsʲkɑ ˈmɔʋɑ]) is a language of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is the official state language of Ukraine. Written Ukrainian uses a Cyrillic alphabet. The language shares some vocabulary with the languages of the neighboring Slavic nations, most notably with Polish, Slovak in the West and Belarusan, Russian in the North and the East.

The Ukrainian language traces its origins to the Old Slavic language of the early medieval state of Kievan Rus'. In its earlier stages it was called Ruthenian. Ukrainian is a lineal descendant of the colloquial language used in Kievan Rus (10th–13th century).[4]

The language has persisted despite several periods of bans and/or discouragement throughout centuries as it has always maintained a sufficient base among the people of Ukraine, its folklore songs, itinerant musicians, and prominent authors.

Contents

|

History

- See also: History of Ukraine

Perspective

Before the eighteenth century the precursor to the modern Ukrainian language was a vernacular language used mostly by peasants and petits bourgeois which existed side-by-side with Church Slavonic, a literary language of religion that evolved from the Old Slavonic. Although the spoken Ukrainian language was in no danger of extinction, it was only raised to the level of a language of literature, philosophy and science by being promoted at the expense of a separate "high language", be it Greek, Church Slavonic, Polish, Latin or Russian.

In 1798 Ivan Kotlyarevsky published an epic poem, Eneyida, a burlesque in Ukrainian, based on Virgil's Aeneid. The book turned out to be the first literary work published in the vernacular Ukrainian, becoming an undying classic of Ukrainian literature. His book was published in vernacular Ukrainian and in satiric way to avoid to be censored, and on this day it is the earliest Ukrainian published book which did survived the Imperial and Soviet policies on the Ukrainian language.

Origin

Ukrainian traces its roots through the mid-fourteenth century Ruthenian language, a chancellery language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, back to the early written evidences of tenth-century Kievan Rus'. One of the key difficulties in tracing the origin of the Ukrainian language more precisely is that until the end of the 18th century the written language used in Ukraine was quite different from the spoken one. For this reason, there is no direct data on the origin of the Ukrainian language. One has to rely on indirect methods: analysis of typical mistakes in old manuscripts, comparison of linguistic data with historical, anthropological, archaeological ones, etc. Because of the difficulty of the question, several theories of the origin of Ukrainian language exist. Some early theories have been proven wrong by modern linguistics (yet are still often cited), while others are still being discussed in the academic community.

Direct written evidence of Ukrainian language existence dates back to the late 16th century.[5] The language itself must have formed earlier, but there are differing opinions as to the exact circumstances and time-frame of its creation.

It is known that between 9th and 13th century, many areas of modern Ukraine, Belarus and parts of Russia were united in a common entity now referred to as Kievan Rus'. Surviving documents from the Kievan Rus' period are written in either Old East Slavic or Old Church Slavonic language or their mixture. Old East Slavic had different dialects in different earldoms of Kievan Rus. These languages are considerably different from both modern Ukrainian and Russian language (but similar enough to allow considerable comprehension of the 11th-century texts by an educated Ukrainian or Russian reader).

In 13th century, eastern parts of Kievan Rus' (including Moscow) came under Tatar yoke until their unification under the Tsardom of Muscovy, whereas in the western areas (including Kiev) the Tatar period, followed by large-scale settlement of Turkic peoples, ended as the territory was incorporated into Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For the following four centuries, the two languages evolved in relative isolation from each other. In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Old Slavic became a language of the chancellery and gradually evolved into the Ruthenian language. By the 1569 Union of Lublin that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a significant part of Ukrainian territory was moved from Lithuanian rule to Polish administration, resulting in the cultural Polonization and attempts to colonize Ukraine by Polish nobility. It is known, for example, that many Ukrainian nobles learned the Polish language and adopted Catholicism during that period.[6] Lower classes have been less affected but as the literacy was limited to the upper class and clergy and the latter was also under the Polish pressure to come into a Union with the Catholic Church that dominated Poland the effect on the literary language has been strong. Most of the educational system gradually Polonized and the most generously funded institutions in the west of Ruthenia had a deteriorating effect on the Ruthenian indigenous culture. In the Polish Ruthenia the language of administrative documents gradually shifted towards Polish. By the 16th century the peculiar official language was formed: a mixture of Old Church Slavonic, Ruthenian language and Polish with the influence of the latter gradually increasing. Documents soon took on Polish characteristics superimposed on Ruthenian phonetics.[7] Much of the influence of Polish on Ukrainian has be attributed to this period.

By the mid 17th century, the linguistic divergence between Ukrainian and Russian languages was so acute that there was a need for translators during negotiations for the Treaty of Pereyaslav, between Bohdan Khmelnytsky, head of the Zaporozhian Host, and the Russian state.

The first theory of the origin of Ukrainian language was suggested in the Imperial Russia in the middle of the 18th century by Mikhail Lomonosov. This theory posits the existence of a common language spoken by all East Slavic people in the time of the Kievan Rus'. According to Lomonosov, the differences that subsequently developed between Great Russian and Ukrainian (then referred to as Little Russian) could be explained by the influence of the Polish and Turkic languages on Ukrainian and the influence of Finnic and Germanic languages on Russian during the period from 13th to 17th century.

The "Polonization" theory was criticized as early as in the first half of the nineteenth century by Mykhailo Maxymovych. In fact, the most distinctive features of the Ukrainian language are present neither in Russian nor in Polish. Ukrainian and Polish language do share many common or similar words, but so do all Slavic languages, since many words originated in the Proto-Slavic language, the common ancestor of all modern Slavic languages. A much smaller part of their common vocabulary can be attributed to the later interaction of the two languages. The "Polonization" theory has not been seriously regarded by the academic community since the beginning of the 20th century, although it is still cited by anti-Ukrainian elements.

Another point of view developed during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by linguists of Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. Similarly to Lomonosov, they assumed the existence of a common language spoken by East Slavs in the past. But unlike Lomonosov's hypothesis, this theory does not view "Polonization" or any other external influence as the main driving force that led to the formation of three different languages: Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian from the common Old East Slavic language. This general point of view is one of the most popular,[8] particularly outside Ukraine. The supporters of this theory disagree, however, about the time when the different languages were formed.

Soviet scholars set the divergence between Ukrainian and Russian only at later time periods (fourteenth through sixteenth centuries). According to this view, Old East Slavic diverged into Belarusian and Ukrainian to the west (collectively, the Ruthenian language of the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries), and Old Russian to the north-east, after the political boundaries of Kievan Rus’ were redrawn in the fourteenth century. During the time of the incorporation of Ruthenia (Ukraine and Belarus) into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Ukrainian and Belarusian diverged into identifiably separate languages.

Some scholars see a divergence between the language of Galicia-Volhynia and the language of Novgorod-Suzdal by the 1100s, assuming that before the 12th century the two languages were practically indistinguishable. This point of view is, however, at variance with some historical data. In fact, several East Slavic tribes, such as Polans, Drevlyans, Severians, Dulebes (that later likely became Volhynians and Buzhans), White Croats, Tiverians and Ulichs lived on the territory of today's Ukraine long before the 12th century. Notably, some Ukrainian features were recognizable in the southern dialects of Old East Slavic as far back as the language can be documented[9].

Some researchers, while admitting the differences between the dialects spoken by East Slavic tribes in the 10th and 11th centuries, still consider them as "regional manifestations of a common language" (see, for instance, the article by Vasyl Nimchuk). In contrast, Ahatanhel Krymsky and Alexei Shakhmatov assumed the existence of the common spoken language of Eastern Slavs only in prehistoric times.[10] According to their point of view, the diversification of the Old East Slavic language took place in the 8th or early 9th century.

A Ukrainian linguist Stepan Smal-Stocky went even further: he denied the existence of a common Old East Slavic language at any time in the past.[11] Similar points of view were shared by Yevhen Tymchenko, Vsevolod Hantsov, Olena Kurylo, Ivan Ohienko and others. According to this theory, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages during the 6th through 9th centuries. The Ukrainian language was formed by convergence of tribal dialects, mostly due to an intensive migration of the population within the territory of today's Ukraine in later historical periods. This point of view was also confirmed by phonological studies of Yuri Shevelov[9] and is gaining a number of supporters among Ukrainian academics.

Medieval history

Beyond the polemics between several ideological conceptions, the continuous presence of Slavic settlements in Ukraine, since at least the sixth century, provides an underlying ethno-linguistic factual basis for the origins of the Ukrainian language. The westernmost areas of modern-day Ukraine lay to the south of the postulated homeland of the original Slavs.

Immigration of Slavic tribes to the Western Slavic and Southern Slavic portions of Eastern Europe led to the dissolution of Early Common Slavic into three groups by the seventh century (East Slavic, West Slavic, and South Slavic). During this time period, some East Slavic elements could have provided a Slavic identity to the Antes civilization (of which nothing but an Iranian name is known).

Rus' and Galicia-Volhynia

During the Khazar period, the territory of Ukraine, settled at that time by Iranian (post-Scythian), Turkic (post-Hunnic, proto-Bulgarian), and Finno-Ugric (proto-Hungarian) tribes, was progressively Slavicized by several waves of migration from the Slavic north. Finally, the Varangian ruler of Novgorod, called Oleg, seized Kiev (Kyiv) and established the political entity of Rus'. Some theorists see an early Ukrainian stage in language development here; others term this era Old East Slavic or Old Ruthenian/Rus'ian. Russian theorists tend to amalgamate Rus' to the modern nation of Russia, and call this linguistic era Old Russian. Some hold that linguistic unity over Rus' was not present, but tribal diversity in language was present.

The era of Rus' is the subject of some linguistic controversy, as the language of much of the literature was purely or heavily Old Slavonic. At the same time, most legal documents throughout Rus' were written in a purely Old East Slavic language (supposed to be based on the Kiev dialect of that epoch). Scholarly controversies over earlier development aside, literary records from Rus' testify to substantial divergence between Russian and Ruthenian/Rusyn forms of the Ukrainian language as early as the era of Rus'. One vehicle of this divergence (or widening divergence) was the large scale appropriation of the Old Slavonic language in the northern reaches of Rus' and of the Polish language at the territory of modern Ukraine. As evidenced by the contemporary chronicles, the ruling princes of Galich (modern Halych) and Kiev called themselves "People of Rus'" (with the exact Cyrillic spelling of the adjective from of Rus' varying among sources), which contrasts sharply with the lack of ethnic self-appellation for the area until the mid-nineteenth century.

One prominent example of this north-south divergence in Rus' from around 1200, was the epic, The Tale of Igor's Campaign. Like other examples of Old Russian literature (for example, Byliny, the Russian Primary Chronicle), it survived only in Northern Russia (Upper Volga belt) and was probably written there. It shows dialectal features characteristic of Severian dialect with the exception of two words which were wrongly interpreted by early nineteenth-century German scholars as Polish loan words.

Under Lithuania/Poland, Muscovy/Russia, and Austro-Hungary

After the fall of Galicia-Volhynia, Ukrainians mainly fell under the rule of Lithuania, then Poland. Local autonomy of both rule and language was a marked feature of Lithuanian rule. Polish rule, which came mainly later, was accompanied by a more assimilationist policy. The Polish language has had heavy influences on Ukrainian (and on Belarusian). As the Ukrainian language developed further, some borrowings from Tatar and Turkish occurred. Ukrainian culture and language flourished in the sixteenth and first half of the seventeenth century, when Ukraine was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Ukrainian was also the official language of Ukrainian provinces of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom. Among many schools established in that time, the Kiev-Mogila Collegium (the predecessor of modern Kyiv-Mohyla Academy), founded by the Orthodox Metropolitan Peter Mogila (Petro Mohyla), was the most important.

In the chaos of the Khmelnytsky Uprising and following wars, Ukrainian high culture was sent into a long period of steady decline. In the aftermath, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was taken over by the Russian Empire. Most of the remaining Ukrainian schools also switched to Polish or Russian, in the territories controlled by these respective countries, which was followed by a new wave of Polonization and Russification of the native nobility. Gradually the official language of Ukrainian provinces under Poland was changed to Polish, while the upper classes in the Russian part of Ukraine used Russian widely.

There was little sense of a Ukrainian nation in the modern sense. East Slavs called themselves Rus’ki ('Russian' pl. adj.) in the east and Rusyny ('Ruthenians' n.) in the west, speaking Rus’ka mova, or simply identified themselves as Orthodox (the latter being particularly important under the rule of Catholic Poland). A part of Ukraine under the Russian Empire was called Little Russia (Malorossija) by the Russian establishment, where the inhabitants were considered to speak the “Little Russian language” (malorossijskij jazyk) or “Southern Russian dialect” (južno-russkie narečie) of the Russian literary language.

During the nineteenth century, a revival of Ukrainian self-identity manifested itself in the literary classes of both Russian-Empire Dnieper Ukraine and Austrian Galicia. The Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius in Kiev applied an old word for the Cossack motherland, Ukrajina, as a self-appellation for the nation of Ukrainians, and Ukrajins’ka mova for the language. Many writers published works in the Romantic tradition of Europe demonstrating that Ukrainian was not merely a language of the village, but suitable for literary pursuits.

However, in the Russian Empire expressions of Ukrainian culture and especially language were repeatedly persecuted, for fear that a self-aware Ukrainian nation would threaten the unity of the Empire. In 1811 by the Order of the Russian government the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was closed. The Academy that was open since 1632 and was the first university in the eastern Europe, was proclaimed to be outlaw. In 1847 the Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius was terminated. The same year Taras Shevchenko was arrested and exiled for ten year, and banned from writing and painting, for political reasons. In 1862 Pavlo Chubynskyi was sent for seven years out of Ukraine to Arkhangelsk. The same year stopped to be published the Ukrainian magazine Osnova. In 1863, tsarist interior minister Pyotr Valuyev proclaimed in his decree that "there never has been, is not, and never can be a separate Little Russian language".[12] A following ban on Ukrainian books led up to Alexander II's secret Ems Ukaz, which prohibited publication and importation of most Ukrainian-language books, public performances and lectures, and even the printing of Ukrainian texts accompanying musical scores.[13] A period of leniency after 1905 was followed by another strict ban in 1914, which also affected Russian-occupied Galicia. (Luckyj 1956:24–25)

For much of the nineteenth century the Austrian authorities demonstrated some preference for Polish culture, but the Ukrainians were relatively free to partake in their own cultural pursuits in Galicia and Bukovyna, where Ukrainian was widely used in education and in official documents.[14] The suppression by Russia retarded the literary development of the Ukrainian language in Dnieper Ukraine, but there was a constant exchange with Galicia, and many works were published under Austria and smuggled to the east.

By the time of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of Austro-Hungary in 1918, the former 'Ruthenians' or 'Little Russians' were ready to openly develop a body of national literature, to institute a Ukrainian-language educational system, and to form an independent state, named Ukraine (the Ukrainian People's Republic, shortly joined by the West Ukrainian People's Republic).

- Further information: Name of Ukraine

Speakers in the Russian Empire

In the Russian Empire Census of 1897 the following picture emerged, with Ukrainian being the second most spoken language of the Russian Empire. According to the Imperial census's terminology, the Russian language (Russkij) was subdivided into Ukrainian (Malorusskij, 'Little Russian'), what we know as Russian today (Vjelikorusskij, 'Great Russian'), and Belarusian (Bjelorusskij, 'White Russian').

The following table shows the distribution of settlement by native language ("po rodnomu jazyku") in 1897, in Russian Empire governorates (guberniyas) which had more than 100,000 Ukrainian speakers.[15]

| Total population | Ukrainian speakers | Russian speakers | Polish speakers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire Russian Empire | 125,640,021 | 22,380,551 | 55,667,469 | 7,931,307 |

| Urban | 16,828,395 | 1,256,387 | 8,825,733 | 1,455,527 |

| Rural | 108,811,626 | 21,124,164 | 46,841,736 | 6,475,780 |

| Regions | ||||

| "European Russia" incl. Ukraine & Belarus |

93,442,864 | 20,414,866 | 48,558,721 | 1,109,934 |

| Vistulan guberniyas | 9,402,253 | 335,337 | 267,160 | 6,755,503 |

| Caucasus | 9,289,364 | 1,305,463 | 1,829,793 | 25,117 |

| Siberia | 5,758,822 | 223,274 | 4,423,803 | 29,177 |

| Central Asia | 7,746,718 | 101,611 | 587,992 | 11,576 |

| Subdivisions | ||||

| Bessarabia | 1,935,412 | 379,698 | 155,774 | 11,696 |

| Volyn | 2,989,482 | 2,095,579 | 104,889 | 184,161 |

| Voronezh | 2,531,253 | 915,883 | 1,602,948 | 1,778 |

| Don Host Province | 2,564,238 | 719,655 | 1,712,898 | 3,316 |

| Yekaterinoslav | 2,113,674 | 1,456,369 | 364,974 | 12,365 |

| Kiev | 3,559,229 | 2,819,145 | 209,427 | 68,791 |

| Kursk | 2,371,012 | 527,778 | 1,832,498 | 2,862 |

| Podolia | 3,018,299 | 2,442,819 | 98,984 | 69,156 |

| Poltava | 2,778,151 | 2,583,133 | 72,941 | 3,891 |

| Taurida | 1,447,790 | 611,121 | 404,463 | 10,112 |

| Kharkov | 2,492,316 | 2,009,411 | 440,936 | 5,910 |

| Kherson | 2,733,612 | 1,462,039 | 575,375 | 30,894 |

| City of Odessa | 403,815 | 37,925 | 198,233 | 17,395 |

| Chernigov | 2,297,854 | 1,526,072 | 495,963 | 3,302 |

| Lublin | 1,160,662 | 196,476 | 47,912 | 729,529 |

| Sedletsk | 772,146 | 107,785 | 19,613 | 510,621 |

| Kuban Province | 1,918,881 | 908,818 | 816,734 | 2,719 |

| Stavropol | 873,301 | 319,817 | 482,495 | 961 |

Soviet era

During the seven-decade-long Soviet era, the Ukrainian language held the formal position of the principal local language in the Ukrainian SSR. However, practice was often a different story: Ukrainian always had to compete with Russian, and the attitudes of the Soviet leadership towards Ukrainian varied from encouragement and tolerance to discouragement and, at times, suppression.

Officially, there was no state language in the Soviet Union. Still it was implicitly understood in the hopes of minority nations that Ukrainian would be used in the Ukrainian SSR, Uzbek would be used in the Uzbek SSR, and so on. However, Russian was used in all parts of the Soviet Union and a special term, "a language of inter-ethnic communication" was coined to denote its status. In reality, Russian was in a privileged position in the USSR and was the state official language in everything but formal name—although formally all languages were held up as equal. Often the Ukrainian language was frowned upon or quietly discouraged which led to the gradual decline in its usage. Partly due to this suppression, in many parts of Ukraine, notably most urban areas of the east and south, Russian remains more widely spoken than Ukrainian.

Soviet language policy in Ukraine is divided into six policy periods

- Ukrainianization and tolerance (1921–1932)

- Persecution and russification (1933–1957)

- Khrushchev thaw (1958–1962)

- The Shelest period: limited progress (1963–1972)

- The Shcherbytsky period: gradual suppression (1973–1989)

- Gorbachev and perestroika (1990–1991)

Ukrainianization and tolerance

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Russian Empire was broken up. In different parts of the former empire, several nations, including Ukrainians, developed a renewed sense of national identity. In the chaotic post-revolutionary years, Ukraine went through several short-lived and quasi-independent states, and the Ukrainian language, gained usage in government affairs. Initially, this trend continued under the Bolshevik government of the Soviet Union, which in a political struggle with the old regime had their own reasons to encourage the national movements of the former Russian Empire. While trying to ascertain and consolidate its power, the Bolshevik government was by far more concerned about many political oppositions connected to the pre-revolutionary order than about the national movements inside the former empire, where it could always find allies.

The widening use of Ukrainian further developed in the first years of Bolshevik rule into a policy called Korenization. The government pursued a policy of Ukrainianization (Ukrayinizatsiya, actively promoting the Ukrainian language), both in the government and among party personnel, and an impressive education program which raised the literacy of the Ukrainophone rural areas. This policy was led by Education Commissar Mykola Skrypnyk. Newly-generated academic efforts from the period of independence were co-opted by the Bolshevik government. The party and government apparatus was mostly Russian-speaking but were encouraged to learn the Ukrainian language. Simultaneously, the newly-literate ethnic Ukrainians migrated to the cities, which became rapidly largely Ukrainianized — in both population and in education.

The policy even reached those regions of southern Russian SFSR where the ethnic Ukrainian population was significant, particularly the areas by the Don River and especially Kuban in the North Caucasus. Ukrainian language teachers, just graduated from expanded institutions of higher education in Soviet Ukraine, were dispatched to these regions to staff newly opened Ukrainian schools or to teach Ukrainian as a second language in Russian schools. A string of local Ukrainian-language publications were started and departments of Ukrainian studies were opened in colleges. Overall, these policies were implemented in thirty-five raions (administrative districts) in southern Russia.

Persecution and russification

Soviet policy towards the Ukrainian language changed abruptly in late 1932 and early 1933, after Stalin had already established his firm control over the party and, therefore, the Soviet state. In December 1932, the regional party cells received a telegram signed by V. Molotov and Stalin with an order to immediately reverse the korenization policies. The telegram condemned Ukrainianization as ill-considered and harmful and demanded to "immediately halt Ukrainianization in raions (districts), switch all Ukrainianized newspapers, books and publications into Russian and prepare by autumn of 1933 for the switching of schools and instruction into Russian".

The following years were characterized by massive repression and many hardships for the Ukrainian language and people. Some historians, especially of Ukraine, emphasize that the repression was applied earlier and more fiercely in Ukraine than in other parts of the Soviet Union, and were therefore anti-Ukrainian; others assert that Stalin's goal was the generic crushing of any dissent, rather than targeting the Ukrainians in particular.

The Stalinist era also marked the beginning of the Soviet policy of encouraging Russian as the language of (inter-ethnic) Soviet communication. Although Ukrainian continued to be used (in print, education, radio and later television programs), it lost its primary place in advanced learning and republic-wide media. Ukrainian was considered to be of secondary importance, and an excessive attachment to it was considered a sign of nationalism and so "politically incorrect". At the same time, however, the new Soviet Constitution adopted in 1936 stipulated that teaching in schools should be in native languages.

Major repression started in 1929–30, when a large group of Ukrainian intelligentsia was arrested and most were executed. In Ukrainian history, this group is often referred to as "Executed Renaissance" (Ukrainian: розстріляне відродження). "Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism" was declared to be the primary problem in Ukraine. The terror peaked in 1933, four to five years before the Soviet-wide "Great Purge", which, for Ukraine, was a second blow. The vast majority of leading scholars and cultural leaders of Ukraine were liquidated, as were the "Ukrainianized" and "Ukrainianizing" portions of the Communist party. Soviet Ukraine's autonomy was completely destroyed by the late 1930s. In its place, the glorification of Russia as the first nation to throw off the capitalist yoke had begun, accompanied by the migration of Russian workers into parts of Ukraine which were undergoing industrialization and mandatory instruction of classic Russian language and literature. Ideologists warned of over-glorifying Ukraine's Cossack past, and supported the closing of Ukrainian cultural institutions and literary publications. The systematic assault upon Ukrainian identity in culture and education, combined with effects of an artificial famine (Holodomor) upon the peasantry—the backbone of the nation—dealt Ukrainian language and identity a crippling blow from which it would not completely recover.

This policy succession was repeated in the Soviet occupation of Western Ukraine. In 1939, and again in the late 1940s, a policy of Ukrainianization was implemented. By the early 1950s, Ukrainian was persecuted and a campaign of Russification began.

Khrushchev thaw

After the death of Stalin (1953), a general policy of relaxing the language policies of the past was implemented (1958 to 1963). The Khrushchev era which followed saw a policy of relatively lenient concessions to development of the languages on the local and republican level, though its results in Ukraine did not go nearly as far as those of the Soviet policy of Ukrainianization in the 1920s. Journals and encyclopedic publications advanced in the Ukrainian language during the Khrushchev era.

Yet, the 1958 school reform that allowed parents to choose the language of primary instruction for their children, unpopular among the circles of the national intelligentsia in parts of the USSR, meant that non-Russian languages would slowly give way to Russian in light of the pressures of survival and advancement. The gains of the past, already largely reversed by the Stalin era, were offset by the liberal attitude towards the requirement to study the local languages (the requirement to study Russian remained). Parents were usually free to choose the language of study of their children (except in few areas where attending the Ukrainian school might have required a long daily commute) and they often chose Russian, which reinforced the resulting Russification. In this sense, some analysts argue that it was not the "oppression" or "persecution", but rather the lack of protection against the expansion of Russian language that contributed to the relative decline of Ukrainian in 1970s and 1980s. According to this view, it was inevitable that successful careers required a good command of Russian, while knowledge of Ukrainian was not vital, so it was common for Ukrainian parents to send their children to Russian-language schools, even though Ukrainian-language schools were usually available. While in the Russian-language schools within the republic, the Ukrainian was supposed to be learned as a second language at comparable level, the instruction of other subjects was in Russian and, as a result, students had a greater command of Russian than Ukrainian on graduation. Additionally, in some areas of the republic, the attitude towards teaching and learning of Ukrainian in schools was relaxed and it was, sometimes, considered a subject of secondary importance and even a waiver from studying it was sometimes given under various, ever expanding, circumstances.

The complete suppression of all expressions of separatism or Ukrainian nationalism also contributed to lessening interest in Ukrainian. Some people who persistently used Ukrainian on a daily basis were often perceived as though they were expressing sympathy towards, or even being members of, the political opposition. This, combined with advantages given by Russian fluency and usage, made Russian the primary language of choice for many Ukrainians, while Ukrainian was more of a hobby. In any event, the mild liberalization in Ukraine and elsewhere was stifled by new suppression of freedoms at the end of the Khrushchev era (1963) when a policy of gradually creeping suppression of Ukrainian was re-instituted.

The next part of the Soviet Ukrainian language policy divides into two eras: first, the Shelest period (early 1960s to early 1970s), which was relatively liberal towards the development of the Ukrainian language. The second era, the policy of Shcherbytsky (early 1970s to early 1990s), was one of gradual suppression of the Ukrainian language.

Shelest period

The Communist Party leader Petro Shelest pursued a policy of defending Ukraine's interests within the Soviet Union. He proudly promoted the beauty of the Ukrainian language and developed plans to expand the role of Ukrainian in higher education. He was removed, however, after only a brief reign, for being too lenient on Ukrainian nationalism.

Shcherbytsky period

The new party boss, Shcherbytsky, purged the local party, was fierce in suppressing dissent, and insisted Russian be spoken at all official functions, even at local levels. His policy of Russification was lessened only slightly after 1985.

Gorbachev and perestroika

The management of dissent by the local Ukrainian Communist Party was more fierce and thorough than in other parts of the Soviet Union. As a result, at the start of the Gorbachev reforms, Ukraine under Shcherbytsky was slower to liberalize than Russia itself.

Although Ukrainian still remained the native language for the majority in the nation on the eve of Ukrainian independence, a significant share of ethnic Ukrainians were Russified. The Russian language was the dominant vehicle, not just of government function, but of the media, commerce, and modernity itself. This was substantially less the case for western Ukraine, which escaped the artificial famine, Great Purge, and most of Stalinism. And this region became the piedmont of a hearty, if only partial, renaissance of the Ukrainian language during independence.

Independence in the modern era

Since 1991, independent Ukraine has made Ukrainian the only official state language and implemented government policies to broaden the use of Ukrainian. The educational system in Ukraine has been transformed over the first decade of independence from a system that is partly Ukrainian to one that is overwhelmingly so. The government has also mandated a progressively increased role for Ukrainian in the media and commerce. In some cases the abrupt changing of the language of instruction in institutions of secondary and higher education led to the charges of Ukrainianization, raised mostly by the Russian-speaking population. However, the transition lacked most of the controversies that surrounded the de-russification in several of the other former Soviet Republics.

With time, most residents, including ethnic Russians, people of mixed origin, and Russian-speaking Ukrainians started to self-identify as Ukrainian nationals, even though remaining largely Russophone. The state became truly bilingual as most of its population had already been. The Russian language still dominates the print media in most of Ukraine and private radio and TV broadcasting in the eastern, southern, and to a lesser degree central regions. The state-controlled broadcast media became exclusively Ukrainian but that had little influence on the audience because of their programs' low ratings. There are few obstacles to the usage of Russian in commerce and it is de facto still occasionally used in the government affairs.

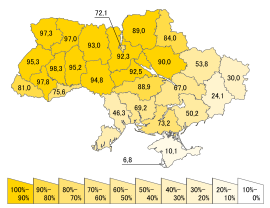

In the 2001 census, 67.5% of the country population named Ukrainian as their native language (a 2.8% increase from 1989), while 29.6% named Russian (a 3.2% decrease). It should be noted, though, that for many Ukrainians (of various ethnic descent), the term native language may not necessarily associate with the language they use more frequently. The overwhelming majority of ethnic Ukrainians consider the Ukrainian language native, including those who often speak Russian and Surzhyk (a blend of Russian vocabulary with Ukrainian grammar and pronunciation). For example, according to the official 2001 census data[16] approximately 75% of Kiev's population responded "Ukrainian" to the native language (ridna mova) census question, and roughly 25% responded "Russian". On the other hand, when the question "What language do you use in everyday life?" was asked in the sociological survey, the Kievans' answers were distributed as follows:[17] "mostly Russian": 52%, "both Russian and Ukrainian in equal measure": 32%, "mostly Ukrainian": 14%, "exclusively Ukrainian": 4.3%. Ethnic minorities, such as Romanians, Tatars and Jews usually use Russian as their lingua franca. But there are tendencies within minority groups to prefer Ukrainian in many situations. The Jewish writer Aleksandr Abramovic Bejderman from the mainly Russian speaking city of Odessa is now writing most of his dramas in Ukrainian. Emotional relationship towards Ukrainian is partly changing in Southern and Eastern areas, too.

However, opposition to expansion of Ukrainian-language teaching remains very strong in eastern regions closer to Russia — in May 2008, the Donetsk city council prohibited the creation of any new Ukrainian schools in the city in which 80% of them are Russian-language schools.[18]

Literature

- See Ukrainian literature

The literary Ukrainian language, which was preceded by Old East Slavic literature, may be subdivided into three stages: old Ukrainian (twelfth to fourteenth centuries), middle Ukrainian (fourteenth to eighteenth centuries), and modern Ukrainian (end of the eighteenth century to the present). Much literature was written in the periods of the old and middle Ukrainian language, including legal acts, polemical articles, science treatises and fiction of all sorts.

Influential literary figures in the development of modern Ukrainian literature include the philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda, Mykola Kostomarov, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, and Lesia Ukrainka. The literary Ukrainian language is based on the dialect of the Poltava region, with some heavy influence from the dialects spoken in the west, notably Galicia (Halychyna). For most of its history, Russian letters were used for written Ukrainian (for example, by Shevchenko). The modern Ukrainian alphabet and orthography, which introduced the distinct letters і, ї, є, ґ, and modified the usage of и, was developed in the late nineteenth century in Austrian-controlled Galicia.

Ukrainophone

A Ukrainophone is somebody who speaks the Ukrainian language.

In the modern nation of Ukraine almost everybody can speak Ukrainian. However, many people are also fluent in Russian as well.

Therefore the nation is sometimes divided into Ukrainophones and Russophones. In English these terms are used to indicate a person's language usage but not their ethnicity.

Current usage

The Ukrainian language is currently emerging from a long period of decline. Although there are almost fifty million ethnic Ukrainians worldwide, including 37.5 million in Ukraine (77.8% of the total population), only in western Ukraine is the Ukrainian language prevalent. In Kiev, both Ukrainian and Russian are spoken, a notable shift from the recent past when the city was primarily Russian speaking. The shift is caused, largely, by an influx of the rural population and migrants from the western regions of Ukraine but also by some Kievans' turning to use the language they speak at home more widely in everyday matters. In northern and central Ukraine, Russian is the language of the urban population, while in rural areas Ukrainian is much more common. In the south and the east of Ukraine, Russian is prevalent even in rural areas, and in Crimea, Ukrainian is almost absent.

Use of the Ukrainian language in Ukraine can be expected to increase, as the rural population (still overwhelmingly Ukrainophone) migrates into the cities and the Ukrainian language enters into wider use in central Ukraine. The literary tradition of Ukrainian is also developing rapidly overcoming the consequences of the long period when its development was hindered by either direct suppression or simply the lack of the state encouragement policies.

The word mova is used for "language" instead of jazyk as in most other Slavic languages, due to semantic differences; mova means "speech" whereas jazyk means "tongue" (note that both these words can mean "language" in English).

Dialects

Several modern dialects of Ukrainian: exist[19][20]

- Northern (Polissian) dialects:[21]

- Eastern Polissian is spoken in Chernihiv (excluding the southeastern districts), in the northern part of Sumy, and in the southeastern portion of the Kiev Oblast as well as in the adjacent areas of Russia, which include the southwestern part of the Bryansk Oblast (the area around Starodub), as well as in some places in the Kursk, Voronezh and Belgorod Oblasts.[22] No linguistic border can be defined. The vocabulary approaches Russian as the language approaches the Russian Federation. Both Ukrainian and Russian grammar sets can be applied to this dialect. Thus, this dialect can be considered a transitional dialect between Ukrainian and Russian.[23]

- Central Polissian is spoken in the northwestern part of the Kiev Oblast, in the northern part of Zhytomyr and the northeastern part of the Rivne Oblast.[24]

- West Polissian is spoken in the northern part of the Volyn Oblast, the northwestern part of the Rivne Oblast as well as in the adjacent districts of the Brest Voblast in Belarus. The dialect spoken in Belarus uses Belarusian grammar, and thus is considered by some to be a dialect of Belarusian.[25]

- Southeastern dialects:[26]

- Middle Dnieprian is the basis of the Standard Literary Ukrainian. It is spoken in the central part of Ukraine, primarily in the southern and eastern part of the Kiev Oblast). In addition, the dialects spoken in Cherkasy, Poltava and Kiev regions are considered to be close to "standard" Ukrainian.

- Slobodan is spoken in Kharkiv, Sumy, Luhansk, and the northern part of Donetsk, as well as in the Voronezh and Belgorod regions of Russia.[27] This dialect is formed from a gradual mixture of Russian and Ukrainian, with progressively more Russian in the northern and eastern parts of the region. Thus, there is no linguistic border between Russian and Ukrainian, and, thus, both grammar sets can be applied. This dialect is a transitional dialect between Ukrainian and Russian.[23]

- A Steppe dialect is spoken in southern and southeastern Ukraine. This dialect was originally the main language of the Zaporozhian Cossacks.[28]

- A Kuban dialect related to the Steppe dialect often referred to as Balachka is spoken by the Kuban Cossacks in the Kuban region in Russia, by the descendants of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who settled in that area in the late eighteenth century. It was formed from gradual mixture of Russian and Ukrainian. This dialect features the use of Russian vocabulary along with Russian grammar.[29] There are 3 main variants according to location.[30]

- Southwestern dialects:[31]

- Boyko is spoken by the Boyko people on the northern side of the Carpathian Mountains in the Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts. It can also be heard across the border in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship of Poland

- Hutsul is spoken by the Hutsul people on the northern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains, in the extreme southern parts of the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, as well as in parts of the Chernivtsi and Transcarpathian Oblasts, .

- Lemko is spoken by the Lemko people, whose homeland rests outside the borders of Ukraine in the Prešov Region of Slovakia along the southern side of the Carpathian Mountains, and in the southeast of modern Poland, along the northern sides of the Carpathians.

- Podillian is spoken in the southern parts of the Vinnytsia and Khmelnytskyi Oblasts, in the northern part of the Odessa Oblast, and in the adjacent districts of the Cherkasy Oblast, the Kirovohrad Oblast and the Mykolaiv Oblast.[32]

- Volynian is spoken in Rivne and Volyn, as well as in parts of Zhytomyr and Ternopil. It is also used in Chełm in Poland.

- Pokuttia (Bukovynian) is spoken in the Chernivtsi Oblast of Ukraine. This dialect has some distinct volcabulary borrowed from Romanian.

- Upper Dniestrian is considered to be the main Galician dialect, spoken in the Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts. Its distinguishing characteristics are the influence of Polish and the German vocabulary, which is reminiscent of the Austro-Hungarian rule. Some of the distinct words used in this dialect can be found here.[33]

- Upper Sannian is spoken in the border area between Ukraine and Poland in the San river valley.

- The Rusyn language is considered by Ukrainian linguists to be a dialect of Ukrainian:

- Dolinian Rusyn or Subcarpathian Rusyn is spoken in the Transcarpathian Oblast.

- Pannonian or Bačka Rusyn is spoken in northwestern Serbia and eastern Croatia. Rusin language of the Bačka dialect is one of the official languages of the Serbian Autonomous Province of Vojvodina).

- Pryashiv Rusyn is the Rusyn spoken in the Prešov (in Ukrainian: Pryashiv) region of Slovakia, as well as by some émigré communities, primarily in the United States of America.

Ukrainian is also spoken by a large émigré population, particularly in Canada (see Canadian Ukrainian), United States and several countries of South America like Argentina. The founders of this population primarily emigrated from Galicia, which used to be part of Austro-Hungary before World War I, and belonged to Poland between the World Wars. The language spoken by most of them is the Galician dialect of Ukrainian from the first half of the twentieth century. Compared with modern Ukrainian, the vocabulary of Ukrainians outside Ukraine reflects less influence of Russian, but often contains many loan words from the local language.

Ukrainian diaspora

Ukrainian is spoken by approximately 36,894,000 people in the world. Most of the countries where it is spoken are ex-USSR where many Ukrainians have migrated. Canada and the United States are also home to a large Ukrainian population. Broken up by country (to the nearest thousand):[34]

- Ukraine 31,058,000

- Russia 4,363,000 (1,815,000 according to the 2002 census)[35]

- Kazakhstan 898,000

- United States 844,000

- Moldova 600,000

- Brazil 300,000 [36]

- Belarus 291,000

- Canada 200,525,[37] 67,665 spoken at home[38] in 2001, 148,000 spoken as "mother tongue" in 2006[39]

- Uzbekistan 153,000

- Poland 150,000[40]

- Kyrgyzstan 109,000

- Argentina 120,000

- United Kingdom 100,000 (Fluent or conversational - see here)

- Latvia 78,000

- Spain 69,000

- Portugal 65,800

- Romania 57,600

- Slovakia 55,000

- Georgia 52,000

- Lithuania 45,000

- Tajikistan 41,000

- Turkmenistan 37,000

- Australia 30,000

- Azerbaijan 29,000

- Paraguay 26,000

- Serbia 21,259 (5,354 Ukrainians and 15,905 Rusyns)[41]

- Estonia 21,000

- Armenia 8,000

- Hungary 4,900 (according to the 2001 census)[42]

Ukrainian is the official language of Ukraine. The language is also one of three official languages of the breakaway Moldovan republic of Transnistria.[43]

Ukrainian is also co-official, alongside Romanian, in ten communes in Suceava County, Romania (as well as Bistra in Maramureş County). In these localities, Ukrainians, who are an officially recognized ethnic minority in Romania, make up more than 20% of the population. Thus, according to Romania's minority rights law, education, signage and access to public administration and the justice system are provided in Ukrainian, alongside Romanian.

Language structure

- Cyrillic letters in this article are romanized using scientific transliteration.

Grammar

- Further information: Ukrainian grammar

Old East Slavic (and Russian) o in closed syllables, that is, ending in a consonant, in many cases corresponds to a Ukrainian i, as in pod->pid (під, ‘under’). Thus, in the declension of nouns, the o can re-appear as it is no longer located in a closed syllable, such as rik (рік, ‘year’) (nom): rotsi (loc) (році).

Ukrainian case endings are somewhat different from Old East Slavic, and the vocabulary includes a large overlay of Polish terminology. Russian na pervom etaže ‘on the first floor’ is in the prepositional case. The Ukrainian corresponding expression is na peršomu poversi (на першому поверсі). -omu is the standard locative (prepositional) ending, but variants in -im are common in dialect and poetry, and allowed by the standards bodies. The kh of Ukrainian poverkh (поверх) has mutated into s under the influence of the soft vowel i (k is similarly mutable into c in final positions). Ukrainian is the only modern East Slavic language which preserves the vocative case.

Sounds

- Further information: Ukrainian phonology

The Ukrainian language has six vowels, /a/, /e/, /ɪ/, /i/, /o/, /u/, and two approximants /j/, /ʋ/.

A number of the consonants come in three forms: hard, soft (palatalized) and long, for example, /l/, /lʲ/, and /ll/ or /n/, /nʲ/, and /nn/.

The letter г represents different consonants in Old East Slavic and Ukrainian. Ukrainian г /ɦ/, often transliterated as Latin h, is the voiced equivalent of Old East Slavic х /x/. The Russian (and Old East Slavic) letter г denotes /g/. Russian-speakers from Ukraine and Southern Russia often use the soft Ukrainian г, in place of the hard Old East Slavic one. The Ukrainian alphabet has the additional letter ґ, for representing /g/, which appears in some Ukrainian words such as gryndžoly (ґринджоли, ‘sleigh’) and gudzyk (ґудзик, ‘button’). However, the letter ґ appears almost exclusively in loan words. This sound is still more rare in Ukrainian than in Czech or Slovak.

Another phonetic divergence between the two languages is the pronunciation of /v/ (Cyrillic в). While in standard Russian it represents /v/, in Ukrainian it denotes both /v/ and /ʋ/ (at the end of a syllable—a labiodental approximant somewhat in between the v in victory and the w in water). Unlike Russian and most other modern Slavic languages, Ukrainian does not have final devoicing.

Alphabet

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| І і | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ю ю | Я я Ь ь |

The alphabet of the Ukrainian language consists of 33 letters and is derived from the Cyrillic writing system. The modern Ukrainian alphabet is the result of a number of proposed alphabetic reforms from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in Ukraine under the Russian Empire, in Austrian Galicia, and later in Soviet Ukraine. A unified Ukrainian alphabet (the Skrypnykivka, after Mykola Skrypnyk) was officially established at a 1927 international Orthographic Conference in Kharkiv, during the period of Ukrainization in Soviet Ukraine. But the policy was reversed in the 1930s, and the Soviet Ukrainian orthography diverged from that used by the diaspora. The Ukrainian letter ge ґ was banned in the Soviet Union from 1933 until the period of Glasnost in 1990.[44]

The alphabet comprises thirty-three letters, representing thirty-eight phonemes (meaningful units of sound), and an additional sign—the apostrophe. Ukrainian orthography is based on the phonemic principle, with one letter generally corresponding to one phoneme, although there are a number of exceptions. The orthography also has cases where the semantic, historical, and morphological principles are applied.

The letter щ represents two consonants [ʃʧ]. The combination of [j] with some of the vowels is also represented by a single letter ([ja]=я, [je]=є, [ji]=ї, [ju]=ю), while [jo]=йо and the rare regional [jɪ]=йи are written using two letters. These iotated vowel letters and a special soft sign change a preceding consonant from hard to soft. An apostrophe is used to indicate the hardness of the sound in the cases when normally the vowel would change the consonant to soft.

A consonant letter is doubled to indicate that the sound is doubled, or long.

The phonemes [ʣ] and [ʤ] do not have dedicated letters in the alphabet and are rendered with the digraphs дз and дж, respectively. [ʣ] is pronounced like English dz in adze, [ʤ] is like g in huge.

- See also Drahomanivka, Ukrainian Latin alphabet.

See also

- Surzhyk

- Balachka

- Swadesh list of Ukrainian words

- Ukrainianization

- Korenizatsiya

- Russification

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ http://www.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/nationality_population/nationality_1/s5/?box=5.1W&out_type=&id=&rz=1_1&rz_b=2_1&k_t=00&id=&botton=cens_db million

- ↑ http://www.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/nationality_population/nationality_6/n56?data1=1&box=5.6W&out_type=&id=&data=1&rz=1_1&k_t=00&id=&botton=cens_db2

- ↑ List_of_languages_by_number_of_native_speakers

- ↑ Ukrainian language, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Лаврентій Зизаній. «Лексис». Синоніма славеноросская

- ↑ The Polonization of the Ukrainian Nobility

- ↑ (Russian) Nikolay Kostomarov, Russian History in Biographies of its main figures, Chapter Knyaz Kostantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky (Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski)

- ↑ "http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9074133?query=Ukrainian%20language&ct=". Retrieved on January 26, 2007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Юрій Шевельов. Історична фонологія української мови

- ↑ Григорій Півторак. Походження українців, росіян, білорусів та їхніх мов

- ↑ Мова (В.В.Німчук). 1. Історія української культури

- ↑ Валуевский циркуляр, full text of the Valuyev circular on Wikisource(Russian)

- ↑ XII. СКОРПІОНИ НА УКРАЇНСЬКЕ СЛОВО. Іван Огієнко. Історія української літературної мови

- ↑ Вiртуальна Русь: Бібліотека

- ↑ Source: demoscope.ru (Russian)

- ↑ "http://ukrcensus.gov.ua/rus/results/general/language/city_kyiv/". Retrieved on November 19, 2005.

- ↑ "Welcome to Ukraine (See above)". Retrieved on November 19, 2005.

- ↑ Ukraine council adopts Russian language, RussiaToday, May 21, 2008

- ↑ Діалект. Діалектизм. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Інтерактивна мапа говорів. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Північне наріччя. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ http://litopys.org.ua/ukrmova/um155.ht

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 http://www.ethnology.ru/doc/narod/t1/gif/nrd-t1_0151z.gif

- ↑ Середньополіський говір. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Maps of Belarus: Dialects on Belarusian territory

- ↑ Південно-східне наріччя. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Слобожанський говір. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Степовий говір. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Viktor Zakharchenko, Folk songs of the Kuban, 1997 Retrieved 07 November 2007]

- ↑ Mapa ukrajinskich howoriv

- ↑ Південно-західне наріччя. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Подільський говір. Українська мова. Енциклопедія

- ↑ Короткий словник львівської ґвари

- ↑ Source, unless specified: Ethnologue

- ↑ 4. РАСПРОСТРАНЕННОСТЬ ВЛАДЕНИЯ ЯЗЫКАМИ (КРОМЕ РУССКОГО)

- ↑ Pacific Island Travel web-site, accessed 4.8.08, taken from: Brazil: the Rough Guide, by David Cleary, Dilwyn Jenkins, Oliver Marshall, Jim Hine. pg. 659. ISBN 1858282233

- ↑ "Various Languages Spoken". Statistics Canada (2001). Retrieved on 2008-02-03.

- ↑ "Detailed Language Spoken at Home". Statistics Canada (2001). Retrieved on 2008-02-03.

- ↑ Mother tongue "refers to the first language learned at home in childhood and still understood by the individual at the time of the census." More detailed language figures are to be reported in December 2007. Statistics Canada (2007). Canada at a Glance 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Officially only 41,000

- ↑ (Serbian) Official Results of Serbian Census 2003–PopulationPDF (441 KiB), pp. 12-13

- ↑ 18. Demográfiai adatok – Központi Statisztikai Hivatal

- ↑ The Constitution of Transnistria, Article 12

- ↑ Magocsi 1996, pp 567, 570–71.

References

- Korunets', Ilko V. (2003). Contrastive Topology of the English and Ukrainian Languages. Vinnytsia: Nova Knyha Publishers,. ISBN 966-7890-27-9.

- Lesyuk, Mykola "Різнотрактування історії української мови".

- Luckyj, George S.N. ([1956] 1990). Literary Politics in the Soviet Ukraine, 1917–1934, revised and updated edition, Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1099-6.

- Nimchuk, Vasyl’. Періодизація як напрямок дослідження генези та історії української мови. Мовознавство. 1997.- Ч.6.-С.3-14; 1998.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- Pivtorak, Hryhoriy Petrovych (1998). Походження українців, росіян, білорусів та їхніх мов (The origin of Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians and their languages). Kiev: Akademia. ISBN 966-580-082-5., (in Ukrainian). Available online.

- Shevelov, George Y. (1979). A Historical Phonology of the Ukrainian Language.. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Verlag. ISBN 3-533-02787-2.. Ukrainian translation is partially available online.

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.

- "What language is spoken in Ukraine", in Welcome to Ukraine, 2003, 1.

- All-Ukrainian population census 2001

- Конституція України (Constitution of Ukraine) (in Ukrainian), 1996, English translation (excerpts).

- 1897 census

External links

- Ethnologue report for Ukrainian

- СЛОВНИК.НЕТ - A monolingual dictionary of modern Ukrainian

- Ukrainian language - the third official? - Ukrayinska Pravda, 28 November 2005

- English-Ukrainian Dictionary

- Ukrainian–English Dictionary

- Dialects of Ukrainian Language / Narzecza Jezyka Ukrainskiego by Wl.Kuraszkiewicz (Polish)

- Hammond's Racial map of Europe, 1919 (English) "National Alumni" 1920, vol.7

- Ethnographic map of Europe 1914 (English)

- Learning Ukrainian, "Kyiv in Your Pocket"

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||