U.S. state

A U.S. state is any one of the fifty subnational entities of the United States of America that share sovereignty with the federal government (four states use the official title of commonwealth rather than state). Because of this shared sovereignty, an American is a citizen both of the federal entity and of his or her state of domicile.[1] However, state citizenship is very flexible, and no government approval is required to move between states (with the exception of convicts on parole).

The United States Constitution allocates power between the two levels of government in general terms. By ratifying the Constitution, each state transfers certain sovereign powers to the federal government. Under the Tenth Amendment, all powers not explicitly transferred are retained by the states and the people. Historically, the tasks of public education, public health, transportation and other infrastructure have been considered primarily state responsibilities, although all have significant federal funding and regulation as well.

Over time, the Constitution has been amended, and the interpretation and application of its provisions have changed. The general tendency has been toward centralization, with the federal government playing a much larger role than it once did. There is a continuing debate over "states' rights", which concerns the extent and nature of the states' powers and sovereignty (in relation to that of the federal government) and their power over individuals.

Union as a single country

Upon the adoption of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union in 1781, the states became a confederation, a single sovereign political entity for the purpose of international law—empowered to levy war and to conduct international relations. In part due to the failings of the Confederation, the thirteen states instead formed a union via the process of ratifying the United States Constitution, which took effect in 1789.

Federal power

Since the 1930s, the Supreme Court of the United States has interpreted the Commerce Clause of the Constitution of the United States in an expansive way that has dramatically expanded the scope of federal power. For example, Congress can regulate railway traffic across state lines, but it may also regulate rail traffic solely within a state, based on the theory that wholly intrastate traffic can still have an impact on interstate commerce.

Another source of Congressional power is its "spending power"—the ability of Congress to impose uniform taxes across the nation and then distribute the resulting revenue back to the states (subject to strict conditions set by Congress). A classic example of this is the system of "federal-aid highways," which includes the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System. The system is mandated and largely funded by the federal government but also serves the interests of the states. By threatening to withhold federal highway funds, Congress has been able to persuade state legislatures to pass a variety of laws. Although some object on the ground that this infringes on states' rights, the Supreme Court has upheld the practice as a permissible use of the Constitution's Spending Clause.

State governments

States are free to organize their state governments any way they like, as long as they conform to the sole requirement of the U.S. Constitution that they have "a Republican Form of Government". In practice, each state has adopted a three branch system of government generally along the same lines as that of the federal government—though this is not a requirement.

Despite the fact that each state has chosen to use the federal model to follow, there are some significant differences in some states. One of the most notable is that of the unicameral Nebraska Legislature, which unlike the legislatures of the other 49 states, has only one house. While there is only one federal President who then selects a Cabinet responsible to him, most states have a plural executive, with members of the executive branch elected directly by the people and serving as equal members of the state cabinet alongside the governor. And only a few states choose to have their judicial branch leaders—their judges on the state's courts—serve for life terms.

A key difference between states is that many rural states have part-time legislatures, while the states with the highest populations tend to have full-time legislatures. Texas, the second largest state in population, is a notable exception to this: excepting special sessions, the Texas Legislature is limited by law to 140 calendar days out of every two years. In Baker v. Carr, the U.S. Supreme Court held that all states are required to have legislative districts which are proportional in terms of population.

States can also organize their judicial systems differently from the federal judiciary, as long as due process is protected. See state court and state supreme court for more information. Most have a trial level court, generally called a District Court or Superior Court, a first-level appellate court, generally called a Court of Appeal (or Appeals), and a Supreme Court. However, Texas has a separate highest court for criminal appeals. New York state is notorious for its unusual terminology, in that the trial court is called the Supreme Court. Appeals are then taken to the Supreme Court, Appellate Division, and from there to the Court of Appeals. Most states base their legal system on English common law (with substantial indigenous changes and incorporation of certain civil law innovations), with the notable exception of Louisiana, which draws large parts of its legal system from French civil law.

Relationships among the states

Under Article IV of the Constitution, which outlines the relationship between the states, the United States Congress has the power to admit new states to the union. The states are required to give "full faith and credit" to the acts of each other's legislatures and courts, which is generally held to include the recognition of legal contracts, marriages, criminal judgments, and—at the time—slave status. States are prohibited from discriminating against citizens of other states with respect to their basic rights, under the Privileges and Immunities Clause. The states are guaranteed military and civil defense by the federal government, which is also required to ensure that the government of each state remains a republic.

Admission of states into the union

Since the establishment of the United States, the number of states has expanded from 13 to 50. The Constitution is rather laconic on the process by which new states can be added, noting only that "New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union", and forbidding a new state to be created out of the territory of an existing state or the merging of two or more states as one without the consent of both Congress and all the state legislatures involved.

In practice, nearly all states admitted to the union after the original thirteen have been formed from U.S. territories (that is, land under the sovereignty of the United States federal government but not part of any state) that were organized (given a measure of self-rule by Congress). Generally speaking, the organized government of a territory would make known the sentiment of its population in favor of statehood; Congress would then direct that government to organize a constitutional convention to write a state constitution. Upon acceptance of that Constitution, Congress would then admit that territory as a state. The broad outlines in this process were established by the Northwest Ordinance, which actually predated the ratification of the Constitution.

However, Congress has ultimate authority over the admission of new states, and is not bound to follow this procedure. A few U.S. states outside of the original 13 have been admitted that were never organized territories of the federal government:

- Vermont, an unrecognized but de facto independent republic until its admission in 1791

- Kentucky, a part of Virginia until its admission in 1792

- Maine, a part of Massachusetts until its admission in 1820 following the Missouri Compromise

- Texas, a recognized independent republic until its admission in 1845

- California, created as a state (as part of the Compromise of 1850) out of the unorganized territory of the Mexican Cession in 1850 without ever having been a separate organized territory itself

- West Virginia, created from areas of Virginia that rejoined the union in 1863, after the 1861 secession of Virginia to the Confederate States of America

Congress is also under no obligation to admit states even in those areas whose population expresses a desire for statehood. For instance, the Republic of Texas requested annexation to the United States in 1836, but fears about the conflict with Mexico that would result delayed admission for nine years. Utah Territory was denied admission to the union as a state for decades because of discomfort with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' dominance in the territory, and particularly with the Mormon elite's then practice of polygamy. Once established, state borders have been largely stable; the only major exceptions are cessions by Maryland and Virginia to create the District of Columbia (Virginia's portion was later returned); a cession by Georgia; expansions by Missouri and Nevada; and Kentucky, Maine, and Tennessee being split from Virginia, Massachusetts, and North Carolina, respectively.

Possible new states

- See also: 51st state, Politics of Puerto Rico, and Political status of Puerto Rico

Today, there are very few U.S. territories left that might potentially become new states. The most likely candidate may be Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico has been under U.S. sovereignty for over a century and Puerto Ricans have been U.S. citizens since 1917. Puerto Rico currently has limited representation in the U.S. Congress in the form of a Resident Commissioner, a nonvoting delegate.[2] President George H. W. Bush issued a memorandum on November 30, 1992 to heads of executive departments and agencies establishing the current administrative relationship between the federal government and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. This memorandum directs all federal departments, agencies, and officials to treat Puerto Rico administratively as if it were a state, insofar as doing so would not disrupt federal programs or operations.

The commonwealth's government has organized several referendums on the question of status over the past several decades, though Congress has not recognized these as binding; all shown resulted in narrow victories for the status quo over statehood, with independence supported by only a small number of voters. On December 23, 2000, President Bill Clinton signed executive Order 13183, which established the President's Task Force on Puerto Rico's Status and the rules for its membership. Section 4 of executive Order 13183 (as amended by executive Order 13319) directs the task force to "report on its actions to the President ... on progress made in the determination of Puerto Rico’s ultimate status."

President George W. Bush signed an additional amendment to Executive Order 13183 on December 3, 2003, which established the current co-chairs and instructed the task force to issue reports as needed, but no less than once every two years. In December 2005, the presidential task force proposed a new set of referendums on the issue; if Congress votes in line with the task force's recommendation, it would pave the way for the first congressionally mandated votes on status in the island, and (potentially) statehood by 2010. The task force's December 2007 status report reiterated and confirmed the proposals made in 2005.[3][4][5]

The intention of the Founding Fathers was that the United States capital should be at a neutral site, not giving favor to any existing state; as a result, the District of Columbia was created in 1800 to serve as the seat of government. The inhabitants of the District do not have full representation in Congress or a sovereign elected government (they were allotted presidential electors by the 23rd amendment, and have a non-voting delegate in Congress). Some residents of the District support statehood of some form for that jurisdiction—either statehood for the whole district or for the inhabited part, with the remainder remaining under federal jurisdiction. While statehood is always a live political question in the District, the prospects for any movement in that direction in the immediate future seem dim. Instead, an emphasis on continuing Home Rule in the District while also giving the District a vote in Congress is gaining support. See also: District of Columbia voting rights

For the remaining permanently inhabited U.S. non-state jurisdictions—the United States Virgin Islands, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa—the prospects of statehood are remote. All have relatively small populations—Guam, with the most inhabitants, has a population less than 35 percent that of Wyoming, the least populous state—and have governments that are heavily reliant on federal funding. If these territories ever sought statehood, they would probably have to combine to maximize their population and territory—possibly with the addition of the former United States Trust Territories: Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands.

Constitutionally, a state may only be divided into more states with the approval both of Congress and of the state's legislature, as was the case when Maine was split off from Massachusetts. When Texas was admitted to the union in 1845, it was much larger than any other state and was specifically granted the right to divide itself into as many as five separate states. However, according to Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution, "New states may be admitted by the Congress into this union; but no new states shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other state; nor any state be formed by the junction of two or more states, or parts of states, without the consent of the legislatures of the states concerned as well as of the Congress." [6][7]

Unrecognized states

- See also: Historical regions of the United States#Unrecognized or self-declared entities

- The State of Franklin existed for four years not long after the end of the American Revolution, but was never recognized by the union, which ultimately recognized North Carolina's claim of sovereignty over the area. A majority of the states were willing to recognize Franklin, but the number of states in favor fell short of the two-thirds majority required to admit a territory to statehood under the Articles of Confederation. The territory comprising Franklin later became part of the state of Tennessee.

- State of Jefferson

- On July 24, 1859, the formation of the proposed State of Jefferson in the Southern Rocky Mountains was defeated by voters. On October 24, 1859, voters instead approved the formation of the Territory of Jefferson, which was superseded by the Territory of Colorado on February 28, 1861.

- In 1915, a second State of Jefferson was proposed for northern third of Texas but failed majority approval of the US congress.

- In 1941 a third State of Jefferson was proposed with more success for ratification for January 1942 in the mostly rural area of southern Oregon and northern California, but was canceled as a result of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. This proposal has been raised several times since.

- State of Lincoln

- State of Lincoln is another state that has been proposed multiple times. It generally consists of the eastern portion of Washington state and the panhandle or northern portion of Idaho. It was originally proposed by Idaho in 1864 to include just the panhandle of Idaho, and again in 1901 to include eastern Washington. Proposals have come up in 1996, 1999, and 2005.

- Lincoln is also the name of a failed state proposal after the U.S. Civil War in 1869. The southwestern section of Texas was proposed to Congress during the Reconstruction period of the federal government after the Civil War.

- State of Muskogee (in Florida, 1800) and State of Sequoyah (in present day Oklahoma, 1905), both unrecognized states with large Native American populations.

Secession

The Constitution is silent on the issue of the secession of a state from the union. The Articles of Confederation had stated that the earlier union of the colonies "shall be perpetual", and the preamble to the Constitution states that Constitution was intended to "form a more perfect union". In 1860 and 1861, eleven southern states seceded, but were brought back into the Union by force of arms during the Civil War. Subsequently, the federal judicial system, in the case of Texas v. White, established that states do not have the right to secede without the consent of the other states.

States called commonwealths

Four of the states bear the formal title of commonwealth: Kentucky, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. In these cases, this is merely a historically based name and has no legal effect. Somewhat confusingly, two U.S. territories—Puerto Rico and the Northern Marianas—are also referred to as commonwealths, and do have a legal status different from the states (both are unincorporated territories).

Origin of states' names

State names speak to the circumstances of their creation. See the lists of U.S. state name etymologies and U.S. county name etymologies.

List of states

The following sortable table lists each of the 50 states of the United States with the following information:

- The common state name

- The preferred pronunciation of the common state name as transcribed with the International Phonetic Alphabet (see Help:Pronunciation for a key)

- The United States Postal Service (USPS) two-character state abbreviation[8]

(also used as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Standard 3166-2 country subdivision code) - The date the state ratified the United States Constitution or was admitted to the Union

- The United States Census Bureau estimate of state population as of July 1, 2007[9][10]

- The state capital

- The most populous incorporated place or Census Designated Place within the state as of 2007-07-01, as estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau[11]

- An image of the official state flag

| Official State Name | Common | IPA | USPS | Flag | Date | Population | Capital | Most Populous City |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State of Alabama | Alabama | /ˌæləˈbæmə/ | AL | 1819-12-14 | 4,627,851 | Montgomery | Birmingham | |

| State of Alaska | Alaska | /əˈlæskə/ | AK | 1959-01-03 | 683,478 | Juneau | Anchorage | |

| State of Arizona | Arizona | /ˌærɪˈzoʊnə/ | AZ | 1912-02-14 | 6,338,755 | Phoenix | Phoenix | |

| State of Arkansas | Arkansas | /ˈɑrkənsɑː/ | AR | 1836-06-15 | 2,834,797 | Little Rock | Little Rock | |

| State of California | California | /ˌkæl |

CA | 1850-09-09 | 36,553,215 | Sacramento | Los Angeles | |

| State of Colorado | Colorado | /ˌkɒləˈrædoʊ/ | CO | 1876-08-01 | 4,861,515 | Denver | Denver | |

| State of Connecticut | Connecticut | /kəˈnɛt |

CT | 1788-01-09 | 3,502,309 | Hartford | Bridgeport[12] | |

| State of Delaware | Delaware | /ˈdɛləwɛər/ | DE | 1787-12-07 | 864,764 | Dover | Wilmington | |

| State of Florida | Florida | /ˈflɔr |

FL | 1845-03-03 | 18,251,243 | Tallahassee | Jacksonville[13] | |

| State of Georgia | Georgia | /ˈdʒɔrdʒə/ | GA | 1788-01-02 | 9,544,750 | Atlanta | Atlanta | |

| State of Hawaii Mokuʻāina o Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian) |

Hawaii | /həˈwaɪi/, [haʋaiʔi] | HI | 1959-08-21 | 1,283,388 | Honolulu | Honolulu | |

| State of Idaho | Idaho | /ˈaɪdəhoʊ/ | ID | 1890-07-03 | 1,499,402 | Boise | Boise | |

| State of Illinois | Illinois | /ɪl |

IL | 1818-12-03 | 12,852,548 | Springfield | Chicago | |

| State of Indiana | Indiana | /ˌɪndiˈænə/ | IN | 1816-12-11 | 6,345,289 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis | |

| State of Iowa | Iowa | /ˈaɪəwə/ | IA | 1846-12-28 | 2,988,046 | Des Moines | Des Moines | |

| State of Kansas | Kansas | /ˈkænzəs/ | KS | 1861-01-29 | 2,775,997 | Topeka | Wichita | |

| Commonwealth of Kentucky | Kentucky | /kənˈtʌki/ | KY | 1792-06-01 | 4,241,474 | Frankfort | Louisville | |

| State of Louisiana État de Louisiane (French) |

Louisiana | /luˌiziˈænə/ | LA | 1812-04-30 | 4,293,204 | Baton Rouge | New Orleans | |

| State of Maine | Maine | /ˈmeɪn/ | ME | 1820-03-15 | 1,317,207 | Augusta | Portland | |

| State of Maryland | Maryland | /ˈmɛrələnd/ | MD | 1788-04-28 | 5,618,344 | Annapolis | Baltimore[14] | |

| Commonwealth of Massachusetts | Massachusetts | /ˌmæsəˈtʃuːs |

MA | 1788-02-06 | 6,449,755 | Boston | Boston | |

| State of Michigan | Michigan | /ˈmɪʃ |

MI | 1837-01-26 | 10,071,822 | Lansing | Detroit | |

| State of Minnesota | Minnesota | /ˌmɪn |

MN | 1858-05-11 | 5,197,621 | Saint Paul | Minneapolis | |

| State of Mississippi | Mississippi | /ˌmɪs |

MS | 1817-12-10 | 2,918,785 | Jackson | Jackson | |

| State of Missouri | Missouri | /m |

MO | 1821-08-10 | 5,878,415 | Jefferson City | Kansas City[15] | |

| State of Montana | Montana | /mɑnˈtænə/ | MT | 1889-11-08 | 957,861 | Helena | Billings | |

| State of Nebraska | Nebraska | /nəˈbræskə/ | NE | 1867-03-01 | 1,774,571 | Lincoln | Omaha | |

| State of Nevada | Nevada | /nəˈvædə/ | NV | 1864-10-31 | 2,565,382 | Carson City | Las Vegas | |

| State of New Hampshire | New Hampshire | /nuˈhæmpʃɚ/ | NH | 1788-06-21 | 1,315,828 | Concord | Manchester[16] | |

| State of New Jersey | New Jersey | /nuˈdʒɝzi/ | NJ | 1787-12-18 | 8,685,920 | Trenton | Newark[17] | |

| State of New Mexico | New Mexico | /nuˈmɛks |

NM | 1912-01-06 | 1,969,915 | Santa Fe | Albuquerque | |

| State of New York | New York | /nuːˈjɔrk/ | NY | 1788-07-26 | 19,297,729 | Albany | New York[18] | |

| State of North Carolina | North Carolina | /ˌnɔrθˌkɛrəˈlaɪnə/ | NC | 1789-11-21 | 9,061,032 | Raleigh | Charlotte | |

| State of North Dakota | North Dakota | /ˌnɔrθdəˈkoʊtə/ | ND | 1889-11-02 | 639,715 | Bismarck | Fargo | |

| State of Ohio | Ohio | /oʊˈhaɪoʊ/ | OH | 1803-03-01 | 11,466,917 | Columbus | Columbus[19] | |

| State of Oklahoma | Oklahoma | /ˌoʊkləˈhoʊmə/ | OK | 1907-11-16 | 3,617,316 | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma City | |

| State of Oregon | Oregon | /ˈɔr |

OR | 1859-02-14 | 3,747,455 | Salem | Portland | |

| Commonwealth of Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania | /ˌpɛns |

PA | 1787-12-12 | 12,432,792 | Harrisburg | Philadelphia | |

| State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | Rhode Island | /roʊdˈaɪlənd/ | RI | 1790-05-29 | 1,057,832 | Providence | Providence | |

| State of South Carolina | South Carolina | /ˌsɑʊθkɛrəˈlaɪnə/ | SC | 1788-05-23 | 4,407,709 | Columbia | Columbia[20] | |

| State of South Dakota | South Dakota | /ˌsɑʊθdəˈkoʊtə/ | SD | 1889-11-02 | 796,214 | Pierre | Sioux Falls | |

| State of Tennessee | Tennessee | /ˌtɛn |

TN | 1796-06-01 | 6,156,719 | Nashville | Memphis[21] | |

| State of Texas | Texas | /ˈtɛksəs/ | TX | 1845-12-29 | 23,904,380 | Austin | Houston[22] | |

| State of Utah | Utah | /ˈjuːtɑː/ | UT | 1896-01-04 | 2,645,330 | Salt Lake City | Salt Lake City | |

| State of Vermont | Vermont | /vɚˈmɑnt/ | VT | 1791-03-04 | 621,254 | Montpelier | Burlington | |

| Commonwealth of Virginia | Virginia | /vɚˈdʒɪnjə/ | VA | 1788-06-25 | 7,712,091 | Richmond | Virginia Beach[23] | |

| State of Washington | Washington | /ˈwɑʃɪŋtən/ | WA | 1889-11-11 | 6,468,424 | Olympia | Seattle | |

| State of West Virginia | West Virginia | /ˌwɛstvɚˈdʒɪnjə/ | WV | 1863-06-20 | 1,812,035 | Charleston | Charleston | |

| State of Wisconsin | Wisconsin | /wɪsˈkɑns |

WI | 1848-05-29 | 5,601,640 | Madison | Milwaukee | |

| State of Wyoming | Wyoming | /waɪˈoʊmɪŋ/ | WY | 1890-07-10 | 522,830 | Cheyenne | Cheyenne |

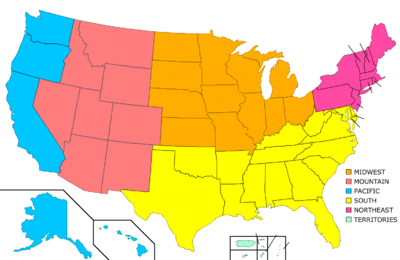

Grouping of the states in regions

The West, The Midwest, The South and The Northeast. Note that Alaska and Hawaii are shown at different scales, and that the Aleutian Islands and the uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are omitted from this map.

States may be grouped in regions; there are endless variations and possible groupings, as most states are not defined by obvious geographic or cultural borders. For further discussion of regions of the U.S., see the list of regions of the United States.

State lists

- List of capitals in the United States

- List of current and former capital cities within U.S. states

- List of U.S. state constitutions

- List of U.S. state legislatures

- List of U.S. state name etymologies

- List of U.S. state residents names

- List of U.S. state tax levels

- List of U.S. states by area

- List of U.S. states by date of statehood

- List of U.S. states by elevation

- List of U.S. states by GDP (nominal)

- List of U.S. states by GDP per capita (nominal)

- List of U.S. states by population

- List of U.S. states by population density

- List of U.S. states by time zone

- List of U.S. states by traditional abbreviation

- List of U.S. states by unemployment rate

- List of U.S. states that were never territories

- List of U.S. states' largest cities

- U.S. postal abbreviations

- U.S. state temperature extremes

- Codes: FIPS state code, ISO 3166-2:US

- Lists of U.S. state insignia

- List of U.S. state amphibians

- List of U.S. state beverages

- List of U.S. state birds

- List of U.S. state butterflies

- List of U.S. state colors

- List of U.S. state dances

- List of U.S. state dinosaurs

- List of U.S. state fish

- List of U.S. state flags

- List of U.S. state flowers

- List of U.S. state foods

- List of U.S. state fossils

- List of U.S. state grasses

- List of U.S. state insects

- List of U.S. state license plates

- List of U.S. state mammals

- List of U.S. state minerals, rocks, stones and gemstones

- List of U.S. state mottos

- List of U.S. state nicknames

- List of U.S. state reptiles

- List of U.S. state seals

- List of U.S. state slogans

- List of U.S. state soils

- List of U.S. state songs

- List of U.S. state sports

- List of U.S. state tartans

- List of U.S. state trees

See also

- 50 State Quarters

- 51st state

- Extreme points of the United States

- Geography of the United States

- List of fictional U.S. states

- List of regions of the United States

- List of U.S. counties that share names with U.S. states

- Organized incorporated territories of the United States

- Political divisions of the United States

- States' rights

- United States Constitution

- United States Declaration of Independence

- United States Declaration of Independence (text)

- United States territorial acquisitions

- United States territory

References

- ↑ See the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

- ↑ Rules of the House of Representatives

- ↑ Report By the President's Task Force On Puerto Rico's Status (December 2005)

- ↑ Report By the President's Task Force On Puerto Rico's Status (December 2007)

- ↑ [1] -Puerto Rico Democracy Act of 2007 H.R. 900

- ↑ http://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/constitution.articleiv.html#section3

- ↑ http://www.snopes.com/history/american/texas.asp

- ↑ "Official USPS Abbreviations" (HTML). United States Postal Service (1998). Retrieved on 2007-02-26.

- ↑ "Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States and States, and for Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007" (CSV). 2007 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division (2007-12-27). Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "United States -- States; and Puerto Rico: GCT-T1-R. Population Estimates (geographies ranked by estimate) Data Set: 2007 Population Estimates" (HTML). 2007 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Estimates Program (2007-07-01). Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population for All Incorporated Places: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007" (CSV). 2007 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division (2008-07-09). Retrieved on 2008-09-08.

- ↑ The Hartford-West Hartford-Willimantic Combined Statistical Area is the most populous metropolitan area in Connecticut.

- ↑ The Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Miami Beach Metropolitan Statistical Area is the most populous metropolitan area in Florida.

- ↑ Baltimore City and the 12 Maryland counties of the Washington-Baltimore-Northern Virginia Combined Statistical Area form the most populous metropolitan region in Maryland.

- ↑ The City of Saint Louis and the 8 Missouri counties of the St. Louis-St. Charles-Farmington Combined Statistical Area form the most populous metropolitan region in Missouri.

- ↑ The 5 southeastern New Hampshire counties of the Boston-Worcester-Manchester Combined Statistical Area form the most populous metropolitan region in New Hampshire.

- ↑ The 13 northern New Jersey counties of the New York-Newark-Bridgeport Combined Statistical Area form the most populous metropolitan region in New Jersey.

- ↑ New York City is the most populous city in the United States.

- ↑ The Cleveland-Akron-Elyria Combined Statistical Area is the most populous metropolitan area in Ohio.

- ↑ The Greenville-Spartanburg-Anderson Combined Statistical Area is the most populous metropolitan area in South Carolina.

- ↑ The Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Columbia Combined Statistical Area is the most populous metropolitan area in Tennessee.

- ↑ The Dallas-Fort Worth Combined Statistical Area is the most populous metropolitan area in Texas.

- ↑ The 10 Virginia counties and 6 Virginia cities of the Washington-Baltimore-Northern Virginia Combined Statistical Area form the most populous metropolitan region in Virginia.

External links

- State Resource Guides, from the Library of Congress

- Tables with areas, populations, densities and more (in order of population)

- Tables with areas, populations, densities and more (alphabetical)

- Origin of State Names

- Rick's Search Assistant—Web links & addresses for many state agencies, e.g., Motor Vehicles, Corporate Records, Attorneys General

- State and Territorial Governments on USA.gov

- StateMaster - statistical database for US States.

- United States Postal Service

- U.S. States: Comparisons, rankings, demographics

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||