Type Ia supernova

A Type Ia supernova is a sub-category of cataclysmic variable stars that results from the violent explosion of a white dwarf star. A white dwarf is the remnant of a star that has completed its normal life cycle and has ceased nuclear fusion. However, white dwarfs of the common carbon-oxygen variety are capable of further fusion reactions that release a great deal of energy if their temperatures rise high enough.

Physically, white dwarfs with a low rate of rotation[2] are limited to masses that are below the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.38[3] solar masses. This is the maximum mass that can be supported by electron degeneracy pressure. Beyond this limit the white dwarf would begin to collapse. If a white dwarf gradually accretes mass from a binary companion, its core is believed to reach the ignition temperature for carbon fusion as it approaches the limit. If the white dwarf merges with another star (a very rare event), it will momentarily exceed the limit and begin to collapse, again raising its temperature past the nuclear fusion ignition point. Within a few seconds of initiation of nuclear fusion, a substantial fraction of the matter in the white dwarf undergoes a runaway reaction, releasing enough energy (1-2 × 1044 joules)[4] to unbind the star in a supernova explosion.[5]

This category of supernovae produces consistent peak luminosity because of the uniform mass of white dwarfs that explode via the accretion mechanism. The stability of this value allows these explosions to be used as standard candles to measure the distance to their host galaxies because the visual magnitude of the supernovae depends primarily on the distance.

Contents |

Consensus model

There are several means by which a supernova of this type can form, but they share a common underlying mechanism. When a slowly-rotating,[2] carbon-oxygen white dwarf accretes matter from a companion, it cannot exceed the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.38 solar masses, beyond which it would no longer be able to support its weight through electron degeneracy pressure[7] and begin to collapse. In the absence of a countervailing process, the white dwarf would collapse to form a neutron star,[8] as normally occurs in the case of a white dwarf that is primarily composed of magnesium, neon and oxygen.[9]

The current view (among astronomers who model Type Ia supernova explosions) is that this limit is never actually attained, however, so that collapse is never initiated. Instead, the increase in pressure and density due to the increasing weight raises the temperature of the core[3], and as the white dwarf approaches to within about 1% of the limit[10], a period of convection ensues, lasting approximately 1,000 years.[11] At some point in this simmering phase, a deflagration flame front is born, powered by carbon fusion. The details of the ignition are still unknown, including the location and number of points where the flame begins.[12] Oxygen fusion is initiated shortly thereafter, but this fuel is not consumed as completely as carbon.[13]

Once fusion has begun, the temperature of the white dwarf starts to rise. A main sequence star supported by thermal pressure would expand and cool in order to counter-balance an increase in thermal energy. However, degeneracy pressure is independent of temperature; the white dwarf is unable to regulate the burning process in the manner of normal stars, and is vulnerable to a runaway fusion reaction. The flame accelerates dramatically, in part due to the Rayleigh–Taylor instability and interactions with turbulence. It is still a matter of considerable debate whether this flame transforms into a supersonic detonation from a subsonic deflagration.[11][14]

Regardless of the exact details of nuclear burning, it is generally accepted that a substantial fraction of the carbon and oxygen in the white dwarf is burned into heavier elements within a period of only a few seconds,[13] raising the internal temperature to billions of degrees. This energy release from thermonuclear burning (1-2 × 1044 joules)[4] is more than enough to unbind the star; that is, the individual particles making up the white dwarf gain enough kinetic energy that they are all able to fly apart from each other. The star explodes violently and releases a shock wave in which matter is typically ejected at speeds on the order of 5–20,000 km/s, or roughly 3% of the speed of light. The energy released in the explosion also causes an extreme increase in luminosity. The typical visual absolute magnitude of Type Ia supernovae is Mv = −19.3 (about 5 billion times brighter than the Sun), with little variation.[11] Whether or not the supernova remnant remains bound to its companion depends on the amount of mass ejected.

The theory of this type of supernovae is similar to that of novae, in which a white dwarf accretes matter more slowly and does not approach the Chandrasekhar limit. In the case of a nova, the infalling matter causes a hydrogen fusion surface explosion that does not disrupt the star.[11] This type of supernova differs from a core-collapse supernova, which is caused by the cataclysmic explosion of the outer layers of a massive star as its core implodes.[15]

Formation

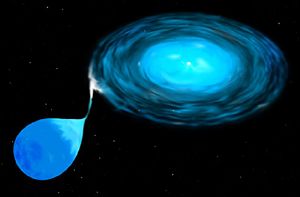

One model for the formation of this category of supernova is a close binary star system. The progenitor binary system consists of main sequence stars, with the primary possessing more mass than the secondary. Being greater in mass, the primary is the first of the pair to evolve onto the asymptotic giant branch, where the star's envelope expands considerably. If the two stars share a common envelope then the system can lose significant amounts of mass, reducing the angular momentum, orbital radius and period. After the primary has degenerated into a white dwarf, the secondary star later evolves in a red giant and the stage is set for mass accretion onto the primary. During this final shared-envelope phase, the two stars spiral in closer together as angular momentum is lost. The resulting orbit can have a period as brief as a few hours.[16][17] If the accretion continues long enough, the white dwarf may eventually approach the Chandrasekhar limit.

A second possible, but much less likely, mechanism for triggering a Type Ia supernova is the merger of two white dwarfs, with the combined mass exceeding the Chandrasekhar limit (which is called a super-Chandrasekhar mass white dwarf).[18][19] In such a case, the total mass would not be constrained by the Chandrasekhar limit. This is one of several explanations proposed for the anomalously massive (2 solar mass) progenitor of the SN 2003fg.[20][21]

Collisions of solitary stars within our galaxy are thought to occur only once every 107–1013 years; far less frequently than the appearance of novae.[22] However, collisions occur with greater frequency in the dense core regions of globular clusters.[23] (cf. blue stragglers) A likely scenario is a collision with a binary star system, or between two binary systems containing white dwarfs. This collision can leave behind a close binary system of two white dwarfs. Their orbit decays and they merge together through their shared envelope.[24]

The white dwarf companion could also accrete matter from other types of companions, including a subgiant or (if the orbit is sufficiently close) even a main sequence star. The actual evolutionary process during this accretion stage remains uncertain, as it can depend both on the rate of accretion and the transfer of angular momentum to the white dwarf companion.[25]

Unlike the other types of supernovae, Type Ia supernovae generally occur in all types of galaxies, including ellipticals. They show no preference for regions of current stellar formation.[26] As white dwarf stars form at the end of a star's main sequence evolutionary period, such a long-lived star system may have wandered far from the region where it originally formed. Thereafter a close binary system may spend another million years in the mass transfer stage (possibly forming persistent nova outbursts) before the conditions are ripe for a Type Ia supernova to occur.[27]

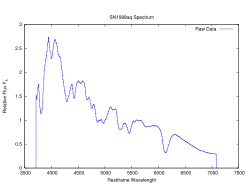

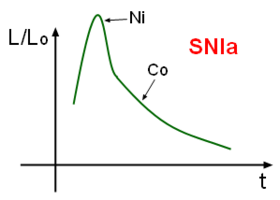

Light curve

Type Ia supernovae have a characteristic light curve, their graph of luminosity as a function of time after the explosion. Near the time of maximum luminosity, the spectrum contains lines of intermediate-mass elements from oxygen to calcium; these are the main constituents of the outer layers of the star. Months after the explosion, when the outer layers have expanded to the point of transparency, the spectrum is dominated by light emitted by material near the core of the star, heavy elements synthesized during the explosion; most prominently isotopes close to the mass of iron (or iron peak elements). The radioactive decay of nickel-56 through cobalt-56 to iron-56 produces high-energy photons which dominate the energy output of the ejecta at intermediate to late times.[11]

The similarity in the absolute luminosity profiles of nearly all known Type Ia supernovae has led to their use as a secondary[28] standard candle in extragalactic astronomy.[29] The cause of this uniformity in the luminosity curve is still an open question. In 1998, observations of distant Type Ia supernovae indicated the unexpected result that the universe seems to undergo an accelerating expansion.[30][31][32][33]

See also

- Carbon detonation

- History of supernova observation

- Supernova remnant

- Extragalactic Distance Scale

References

- ↑ Krause, Oliver; Tanaka, Masaomi; Usuda, Tomonori; Hattori, Takashi; Goto, Miwa; Birkmann, Stephan; Nomoto, Ken'ichi (2008-10-28). "Tycho Brahe's 1572 supernova as a standard type Ia explosion revealed from its light echo spectrum". arXiv.org. Retrieved on 2008-12-06.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Yoon, S.-C.; Langer, L. (2004). "Presupernova Evolution of Accreting White Dwarfs with Rotation". Astronomy and Astrophysics 419 (2): 623. doi:. http://www.citebase.org/fulltext?format=application%2Fpdf&identifier=oai%3AarXiv.org%3Aastro-ph%2F0402287. Retrieved on 2007-05-30.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mazzali, P. A.; K. Röpke, F. K.; Benetti, S.; Hillebrandt, W. (2007). "A Common Explosion Mechanism for Type Ia Supernovae". Science 315 (5813): 825–828. doi:.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Khokhlov, A.; Mueller, E.; Hoeflich, P. (1993). "Light curves of Type IA supernova models with different explosion mechanisms". Astronomy and Astrophysics 270 (1-2): 223–248. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/bib_query?1993A%26A...270..223K. Retrieved on 2007-05-22.

- ↑ Staff (2006-09-07). "Introduction to Supernova Remnants". NASA Goddard/SAO. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Matheson, Thomas; Kirshner, Robert; Challis, Pete; Jha, Saurabh (2008), "Optical Spectroscopy of Type Ia Supernovae", Astronomical Journal, http://arxiv.org/abs/0803.1705, retrieved on 2008-05-19

- ↑ Lieb, E. H.; Yau, H.-T. (1987). "A rigorous examination of the Chandrasekhar theory of stellar collapse". Astrophysical Journal 323 (1): 140–144. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1987ApJ...323..140L. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Canal, R.; Gutiérrez, J. (1997). "The possible white dwarf-neutron star connection". Astrophysics and Space Science Library 214: 49. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1997astro.ph..1225C. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Fryer, C. L.; New, K. C. B. (2006-01-24). "2.1 Collapse scenario". Gravitational Waves from Gravitational Collapse. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Retrieved on 2007-06-07.

- ↑ Wheeler, J. Craig (2000-01-15). Cosmic Catastrophes: Supernovae, Gamma-Ray Bursts, and Adventures in Hyperspace. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. p. 96. ISBN 0521651956. http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521857147.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Hillebrandt, W.; Niemeyer, J. C. (2000). "Type IA Supernova Explosion Models". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 38: 191–230. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000ARA&A..38..191H. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ "Science Summary". ASC / Alliances Center for Astrophysical Thermonuclear Flashes (2001). Retrieved on 2006-11-27.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Röpke, F. K.; Hillebrandt, W. (2004). "The case against the progenitor's carbon-to-oxygen ratio as a source of peak luminosity variations in Type Ia supernovae". Astronomy and Astrophysics 420: L1–L4.

- ↑ Gamezo, V. N.; Khokhlov, A. M.; Oran, E. S.; Chtchelkanova, A. Y.; Rosenberg, R. O. (2003-01-03). "Thermonuclear Supernovae: Simulations of the Deflagration Stage and Their Implications". Science 299 (5603): 77–81. doi:. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/299/5603/77. Retrieved on 2006-11-28.

- ↑ Gilmore, Gerry (2004). "The Short Spectacular Life of a Superstar". Science 304 (5697): 1915–1916. doi:. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/sci;304/5679/1915. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Paczynski, B. (July 28-August 1, 1975). "Common Envelope Binaries". Structure and Evolution of Close Binary Systems: 75–80, Cambridge, England: Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co.. Retrieved on 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Postnov, K. A.; Yungelson, L. R. (2006). "The Evolution of Compact Binary Star Systems". Living Reviews in Relativity. Retrieved on 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Staff. "Type Ia Supernova Progenitors". Swinburne University. Retrieved on 2007-05-20.

- ↑ "Brightest supernova discovery hints at stellar collision", New Scientist (2007-01-03). Retrieved on 2007-01-06.

- ↑ "The Weirdest Type Ia Supernova Yet", Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (2006-09-20). Retrieved on 2006-11-02.

- ↑ "Bizarre Supernova Breaks All The Rules", New Scientist (2006-09-20). Retrieved on 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Whipple, Fred L. (1939). "Supernovae and Stellar Collisions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 25 (3): 118–125. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1939PNAS...25..118W. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Rubin, V. C.; Ford, W. K. J. (1999). "A Thousand Blazing Suns: The Inner Life of Globular Clusters". Mercury 28: 26. http://www.astrosociety.org/pubs/mercury/9904/murphy.html. Retrieved on 2006-06-02.

- ↑ Middleditch, J. (2004). "A White Dwarf Merger Paradigm for Supernovae and Gamma-Ray Bursts". The Astrophysical Journal 601 (2): L167–L170. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003astro.ph.11484M. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Langer, N.; Yoon, S.-C.; Wellstein, S.; Scheithauer, S. (2002). "On the evolution of interacting binaries which contain a white dwarf". The Physics of Cataclysmic Variables and Related Objects, ASP Conference Proceedings: 252, San Francisco, California: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ↑ van Dyk, Schuyler D. (1992). "Association of supernovae with recent star formation regions in late type galaxies". Astronomical Journal 103 (6): 1788–1803. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1992AJ....103.1788V. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Langer, N.; Deutschmann, A.; Wellstein, S.; Höflich, P. (1999). "The evolution of main sequence star + white dwarf binary systems towards Type Ia supernovae". Astronomy and Astrophysics 362: 1046–1064. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000astro.ph..8444L. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Macri, L. M.; Stanek, K. Z.; Bersier, D.; Greenhill, L. J.; Reid, M. J. (2006). "A New Cepheid Distance to the Maser-Host Galaxy NGC 4258 and Its Implications for the Hubble Constant". Astrophysical Journal 652 (2): 1133–1149. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-bib_query?bibcode=2006ApJ...652.1133M. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Colgate, S. A. (1979). "Supernovae as a standard candle for cosmology". Astrophysical Journal 232 (1): 404–408. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1979ApJ...232..404C. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Perlmutter, S.; et al. (The Supernova Cosmology Project) (1999). "Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 high redshift supernovae" (subscription required). Astrophysical Journal 517: 565–86. doi:. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9812133.

- ↑ Riess, Adam G.; et al. (Supernova Search Team) (1998). "Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant" (subscription required). Astronomical Journal 116: 1009–38. doi:. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9805201.

- ↑ Leibundgut, B.; Sollerman, J. (2001). "A cosmological surprise: the universe accelerates". Europhysics News 32 (4). http://www.eso.org/~bleibund/papers/EPN/epn.html. Retrieved on 2007-02-01.

- ↑ "Confirmation of the accelerated expansion of the Universe", Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (2003-09-19). Retrieved on 2006-11-03.

External links

- Falck, Bridget (2006). "Type Ia Supernova Cosmology with ADEPT". Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved on 2007-05-20.

- Staff (February 27, 2007). "Sloan Supernova Survey". Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- "Novae and Supernovae". peripatus.gen.nz. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- "Source for major type of supernova". Pole Star Publications Ltd (August 6, 2003). Retrieved on 2007-11-25. (A Type Ia progenitor found)

- "Novae and Supernovae explosions found". peripatus.gen.nz. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

|

||||||||