Twin

Twins are offspring resulting from the same pregnancy, which can be the same or opposite gender.

The general term for more than one offspring from the same pregnancy (multiple birth) is multiples, for example triplets refers to cases of three offspring from the same pregnancy. A fetus alone in the womb is called a singleton.

Twins are usually born in close succession. Due to the limited size of the mother's womb, multiple pregnancies are much less likely to carry to full term than singleton births, with twin pregnancies lasting only 37 weeks on average, 3 weeks less than full term.[1] Since premature births can have health consequences for the babies, twin births are often handled with special precautions.

Twins can either be monozygotic (MZ, colloquially, "identical") or dizygotic (DZ, colloquially, "fraternal"). There are estimated to be approximately 125 million human twins and triplets in the world (roughly 1.9% of the world population), and just 10 million monozygotic twins (roughly 0.2% of the world population and 8% of all twins).[2] The current rate in the United States is 31 twin births per 1,000 women.[3]

The Yoruba, a large west African ethnic group, have the highest rate of twinning in the world at 45 twins per 1000 live births.[4][5][6] Some researchers have claimed this may be because of high consumption of a specific type of yam, Dioscorea rotundata or white yam containing a natural hormone phytoestrogen which may stimulate the ovaries to produce an egg from each side.[7][8]

Contents |

Types of twins

There are five common variations of twinning. The three most common variations are all dizygotic:

- male-female twins are the most common result, at about 40 percent of all twins born

- female DZ twins (sometimes called sororal twins)

- male DZ twins.

The other two variations are monozygotic twins:

- female MZ twins

- male MZ twins (least common).

Among non-twin births, male singletons are slightly (about five percent) more common than female singletons. There is also the mirror image variations: This is where the twins develop reverse asymmetric features. About 25% of monozygotic twins are mirror image twins. The rates for singletons vary slightly by country. For example, the sex ratio of birth in the US is 1.05 males/female,[9] while it is 1.07 males/female in Italy.[10] However, males are also more susceptible than females to death in utero, and since the death rate in utero is higher for twins, it leads to female twins being more common than male twins.

Another variety of twins, "polar body twins," is a phenomenon that was hypothesized to occur and may recently have been proven, very rarely, to exist. This would occur when a portion of a mature egg separates itself from the egg. This is known as the first polar body, and it carries all the same genetic information as the egg. If polar body twins are fact, they would occur when two sperm fertilize both the egg and the first polar body. Generally the first polar body disintegrates. Polar body twinning would result in "half-identical" twins.[11]

Dizygotic twins

Dizygotic twins (commonly known as fraternal twins, but also referred to as non-identical twins or biovular twins) usually occur when two fertilized eggs are implanted in the uterine wall at the same time. When two eggs are independently fertilized by two different sperm cells, DZ twins result. The two eggs, or ova, form two zygotes, hence the terms dizygotic and biovular.

Dizygotic twins, like any other siblings, have an extremely small chance of having the exact same chromosome profile. Like any other siblings, DZ twins may look similar, particularly given that they are the same age. However, DZ twins may also look very different from each other. They may be of different sexes or the same sex. The same holds true for brothers and sisters from the same parents, meaning that DZ twins are simply brothers and/or sisters who happen to have the same age.

Studies show that there is a genetic basis for DZ twinning. However, it is only their mother that has any effect on the chances of having DZ twins; there is no known mechanism for a father to cause release of more than one ovum. Dizygotic twinning ranges from six per thousand births in Japan (similar to the rate of monozygotic twins) to 14 and more per thousand in some African countries.[7]

DZ twins are also more common for older mothers, with twinning rates doubling in mothers over the age of 35.[12] With the advent of technologies and techniques to assist women in getting pregnant, the rate of fraternals has increased markedly. For example, in New York City's Upper East Side there were 3,707 twin births in 1995; there were 4,153 in 2003; and there were 4,655 in 2004. Triplet births have also risen, from 60 in 1995 to 299 in 2004. The German For DZ twins is Zweieiiger Zwilling Meaning Literally: 2 egg twins.

Monozygotic twins

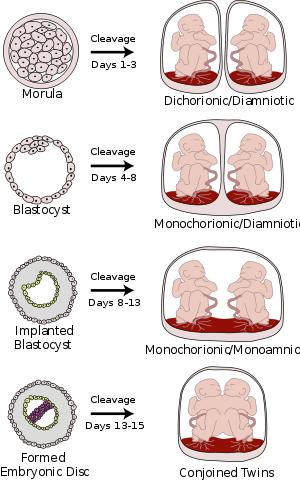

Monozygotic twins, frequently referred to as identical twins, occur when a single egg is fertilized to form one zygote (monozygotic) which then divides into two separate embryos. Their traits and physical appearances are not exactly the same; although they have nearly identical DNA,[13] environmental conditions both inside the womb and throughout their lives influence the switching on and off of various genes. Division of the zygote into two embryos is not considered to be a hereditary trait, but rather an anomaly that occurs in birthing at a rate of about three in every 1000 deliveries worldwide,[14] regardless of race. The two embryos develop into fetuses sharing the same womb. When one egg is fertilized by one sperm cell, and then divides and separates, two identical cells will result. If the zygote splits very early (in the first two days after fertilization), each cell may develop separately its own placenta (chorion) and its own sac (amnion). These are called dichorionic diamniotic (di/di) twins, which occurs 18–36% of the time.[15] Most of the time in MZ twins the zygote will split after two days, resulting in a shared placenta, but two separate sacs. These are called monochorionic diamniotic (mono/di) twins, occurring 60–70% of the time.[15]

In about 1–2% of MZ twinning the splitting occurs late enough to result in both a shared placenta and a shared sac called monochorionic monoamniotic (mono/mono) twins.[15] Finally, the zygote may split extremely late, resulting in conjoined twins. Mortality is highest for conjoined twins due to the many complications resulting from shared organs. Mono/mono twins have an overall in-utero mortality of about 50 percent, principally due to cord entanglement prior to 32 weeks gestation. If expecting parents choose hospitalization, mortality can decrease through consistent monitoring of the babies. Hospitalization can occur beginning at 24 weeks, but doctors prefer a later date to prevent any complications due to premature births. The choice is up to the parents when to start hospitalization. Many times, monoamniotic twins are delivered at 32 weeks electively for the safety of the babies. In higher order multiples, there can sometimes be a combination of DZ and MZ twins.

Mono/di twins have about a 25 percent mortality due to twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Di/di twins have the lowest mortality risk at about 9 percent, although that is still significantly higher than that of singletons.[16]

Monozygotic twins are genetically identical (unless there has been a mutation in development) and they are always the same sex. On rare occasions, monozygotic twins may express different phenotypes, normally due to an environmental factor or the deactivation of different X chromosomes in monozygotic female twins, and in some extremely rare cases, due to aneuploidy, twins may express different sexual phenotypes, normally due to an XXY Klinefelter's syndrome zygote splitting unevenly[17][18]). Monozygotic twins look alike, although they do not have the same fingerprints (which are environmental as well as genetic). As they mature, MZ twins often become less alike because of lifestyle choices or external influences. Genetically speaking, the children of MZ twins are half-siblings rather than cousins. If each member of one set of MZ twins reproduces with one member of another set of MZ twins then the resulting children would be genetic full siblings. It is estimated that there are around 10 million monozygotic twins and triplets in the world.

The likelihood of a single fertilisation resulting in MZ twins appears to be a random event, not a hereditary trait, and is uniformly distributed in all populations around the world.[12] This is in marked contrast to DZ twinning, which ranges from about six per thousand births in Japan (almost similar to the rate of MZ twins, which is around 4-5 to 15 and more per thousand in some parts of India[19]) and up to 24 in the US, which might mainly be due to IVF (in vitro fertilisation). The exact cause for the splitting of a zygote or embryo is unknown.

Monozygotic twins have nearly identical DNA, but differing environmental influences throughout their lives affect which genes are switched on or off. This is called epigenetic modification. A study of 80 pairs of human twins ranging in age from three to 74 showed that the youngest twins have relatively few epigenetic differences. The number of epigenetic differences between MZ twins increases with age. Fifty-year-old twins had over three times the epigenetic difference of three-year-old twins. Twins who had spent their lives apart (such as those adopted by two different sets of parents at birth) had the greatest difference.[20] However, certain characteristics become more alike as twins age, such as IQ and personality.[21][22] This phenomenon illustrates the influence of genetics in many aspects of human characteristics and behaviour.

A recent theory posits that monozygotic twins are formed after a blastocyst essentially collapses, splitting the progenitor cells (those that contain the body's fundamental genetic material) in half. That leaves the same genetic material divided in two on opposite sides of the embryo. Eventually, two separate fetuses develop. The research was presented at a meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology in Lyon, France. Utilizing computer software to take photos every two minutes of 33 embryos growing in a laboratory, Dr. Dianna Payne, a visiting research fellow at the Mio Fertility Clinic in Japan, documented for the first time the early days of twin development. Payne also discovered explanation for why in-vitro fertilization techniques are more likely to create twins. Only about three pairs of twins per 1,000 deliveries occur as a result of natural conception, while for IVF deliveries, there are nearly 21 pairs of twins for every 1,000.[23][24]

Zygosity, chorionicity and amniocity

The two types of twins discussed before, monozygotic and dizygotic, are generally referred to as zygocity. Zygocity reflects the genetic type of twins. Two others terms define twin types: chorionity and amniocity. Chorionity refers to the number of chorionic sacs, while amniocity refers to the number of amniotic sacs. The number of chorionic and amnionic sacs can sometimes reveal the zygocity. Monoamniotic twins indicate monozygotic twins. However, two placentas does not provide information about zygocity since monozygotic twins can have two placentas. Chorionicity and amniocity are a result of the division time. Dichorionic twins divide within the first 4 days. Monoamnionic twins divide after the first week.

Demographics

A recent study found that vegan mothers are five times less likely to have twins than those who eat animal products.[25]

From 1980–97, the number of twin births in the United States rose 52%.[26] This rise can at least partly be attributed to the increasing popularity of fertility drugs like Clomid and procedures such as in vitro fertilization, which result in multiple births more frequently than unassisted fertilizations do. It may also be linked to the increase of growth hormones in food.[25]

Ethnicity

About 1 in 90 human births (1.1%) results from a twin pregnancy.[27] The rate of dizygotic twinning varies greatly among ethnic groups, ranging as high as about 45 per 1000 births for the Yoruba to 10% for Linha Sao Pedro, a tiny Brazilian village.[28] The widespread use of fertility drugs causing hyperovulation (stimulated release of multiple eggs by the mother) has caused what some call an "epidemic of multiple births". In 2001, for the first time ever in the US, the twinning rate exceeded 3% of all births. Nevertheless, the rate of monozygotic twins remains at about 1 in 333 across the globe.

In a study on the maternity records of 5750 Hausa women living in the Savannah zone of Nigeria, there were 40 twins and 2 triplets/1000 births. Twenty six per cent of twins were monozygous. The incidence of multiple births, which was about five times higher than that observed in any western population, was significantly lower than that of other ethnic groups, who live in the hot and humid climate of the southern part of country. The incidence of multiple births was related to maternal age but did not bear any association to the climate or prevalence of malaria.[29]

Predisposing factors

The predisposing factors of monozygotic twinning are unknown.

Dizygotic twin pregnancies are slightly more likely when the following factors are present in the woman:

- She is of West African descent (especially Yoruba)

- She is between the age of 30 and 40 years

- She is greater than average height and weight

- She has had several previous pregnancies.

- She has a family history of dizygotic twinning, especially a mother who is a twin.

Women undergoing certain fertility treatments may have a greater chance of dizygotic multiple births. This can vary depending on what types of fertility treatments are used. With in vitro fertilisation (IVF), this is primarily due to the insertion of multiple embryos into the uterus. Some other treatments such as the drug Clomid can stimulate a woman to release multiple eggs, allowing the possibility of multiples. Many fertility treatments have no effect on the likelihood of multiple births.

Complications of twin pregnancy

Vanishing twins

Researchers suspect that as many as 1 in 8 pregnancies start out as multiples, but only a single fetus is brought to full term, because the other has died very early in the pregnancy and not been detected or recorded.[30] Early obstetric ultrasonography exams sometimes reveal an "extra" fetus, which fails to develop and instead disintegrates and vanishes. This is known as vanishing twin syndrome.

Conjoined twins

Conjoined twins (or "Siamese twins") are monozygotic twins whose bodies are joined together during pregnancy. This occurs where the single zygote of MZ twins fails to separate completely, and the zygote starts to split after day 13 following fertilization. This condition occurs in about 1 in 50,000 human pregnancies. Most conjoined twins are now evaluated for surgery to attempt to separate them into separate functional bodies. The degree of difficulty rises if a vital organ or structure is shared between twins, such as the brain, heart or liver.

Chimerism

A chimera is an ordinary person or animal except that some of their parts actually came from their twin or from the mother. A chimera may arise either from monozygotic twin fetuses (where it would be impossible to detect), or from dizygotic fetuses, which can be identified by chromosomal comparisons from various parts of the body. The number of cells derived from each fetus can vary from one part of the body to another, and often leads to characteristic mosaicism skin colouration in human chimeras. A chimera may be a hermaphrodite, composed of cells from a male twin and a female twin.

Parasitic twins

Sometimes one twin fetus will fail to develop completely and continue to cause problems for its surviving twin. One fetus acts as a parasite towards the other. Sometimes the parasitic twin becomes an almost indistinguishable part of the other, and sometimes this needs to be medically dealt with.

Partial molar twins

A very rare type of parasitic twinning is one where a single viable twin is endangered when the other zygote becomes cancerous, or molar. This means that the molar zygote's cellular division continues unchecked, resulting in a cancerous growth that overtakes the viable fetus. Typically, this results when one twin has either triploidy or complete paternal uniparental disomy, resulting in little or no fetus and a cancerous, overgrown placenta, resembling a bunch of grapes.

Miscarried twin

Occasionally, a woman will suffer a miscarriage early in pregnancy, yet the pregnancy will continue; one twin was miscarried but the other was able to be carried to term. This occurrence is similar to the vanishing twin syndrome, but typically occurs later than the vanishing twin syndrome.

Low birth weight

Twins typically suffer from the lower birth weights and greater likelihood of prematurity that is more commonly associated with the higher multiple pregnancies. Throughout their lives twins tend to be smaller than singletons on average.

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Monozygotic twins who share a placenta can develop twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. This condition means that blood from one twin is being diverted into the other twin. One twin, the 'donor' twin, is small and anemic, the other, the 'recipient' twin, is large and polycythemic. The lives of both twins are endangered by this condition.

Human twin studies

Twin studies are studies that assess monozygotic twins for medical, genetic, or psychological characteristics to try to isolate genetic influence from epigenetic and environmental influence. Twins that have been separated early in life and raised in separate households are especially sought-after for these studies, which have been invaluable in the exploration of human nature.

Twin studies are called consanguity studies, observing the differences or similarities of twins in different environments to see how much of their behavior is attributable to genetics or environmental influence.

Unusual twinnings

There are some patterns of twinning that are exceedingly rare: while they have been reported to happen, they are so unusual that most obstetricians or midwives may go their entire careers without encountering a single case.

Among dizygotic twins, in rare cases, the eggs are fertilized at different times with two or more acts of sexual intercourse, either within one menstrual cycle (superfecundation) or, even more rarely, later on in the pregnancy (superfetation). This can lead to the possibility of a woman carrying fraternal twins with different fathers (that is, half-siblings). This phenomenon is known as heteropaternal superfecundation. One 1992 study estimates that the frequency of heteropaternal superfecundation among dizygotic twins whose parents were involved in paternity suits was approximately 2.4%; see the references section, below, for more details.

Dizygotic twins from biracial couples can sometimes be mixed twins - which exhibit differing ethnic and racial features. One such pairing was born in Germany in 2008 to a white father from Germany and a black mother from Ghana.[31]

Among monozygotic twins, in extremely rare cases, twins have been born with opposite sexes (one male, one female). The probability of this is so vanishingly small (only 3 documented cases[32]) that multiples having different sexes is universally accepted as a sound basis for a clinical determination that in utero multiples are not monozygotic. When monozygotic twins are born with different sexes it is because of chromosomal birth defects. In this case, although the twins did come from the same egg, it is incorrect to refer to them as genetically identical, since they have different karyotypes.

Semi-identical twins

- See also: half twin

Monozygotic twins can develop differently, due to different genes being activated.[33] More unusual are "semi-identical twins". These "half-identical twins" are hypothesized to occur when an unfertilized egg cleaves into two identical attached ova and which are viable for fertilization. Both cloned ova are then fertilized by different sperm and the coalesced eggs undergo further cell duplications developing as a chimeric blastomere. If this blastomere then undergoes a twinning event, two embryos will be formed, each of which have different paternal genes and identical maternal genes.

This results in a set of twins with identical genes from the mother's side, but different genes from the father's side. Cells in each fetus carry genes from either sperm, resulting in chimeras. This form had been speculated until only recently being recorded in western medicine.[34][35][36]

Animal twins

Twins are common in many animal species, such as cats, sheep, ferrets and deer. The incidence of twinning among cattle is about 1–4%, and research is under way to improve the odds of twinning, which can be more profitable for the breeder if complications can be sidestepped or managed. A species of armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) has identical twins (usually four babies) as its regular reproduction and not as exceptional cases.

See also

- Evil twin

- Gemini

- Incest between twins

- List of multiple births

- List of twins

- Look-alike

- Litter (animal)

- Multiple birth

References

- ↑ Elliott, JP (December 2007). "Preterm labor in twins and high-order multiples.". Clinical Perinatology 34 (4): 599–609. doi:. PMID 18063108. "Unlike singleton gestation where identification of patients at risk for PTL is often difficult, every multiple gestation is at risk for PTL, so all patients can be managed as being at risk.".

- ↑ Oliver, Judith (2006). "Twin Resources". Economic and Social Research Council. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ "Birth Statistics". Rush University Medical Center. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ Zach, Terence; Arun K Pramanik and Susannah P Ford (2007-10-02). "Multiple Births". WebMD. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ "Genetics or yams in the Land of Twins?", Independent Online (2007-11-12). Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ "The Land Of Twins", BBC World Service (2001-06-07). Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 O. Bomsel-Helmreich; W. Al Mufti (1995). "The mechanism of monozygosity and double ovulation". in Louis G. Keith, Emile Papierik, Donald M. Keith and Barbara Luke. Multiple Pregnancy: Epidemiology, Gestation & Perinatal Outcome. Taylor and Francis. pp. 34. ISBN 1-85070-666-2.

- ↑ "What’s in a yam? Clues to fertility, a student discovers" (1999). Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ "United States: People". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (2008-09-04). Retrieved on 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "Italy: People". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (2008-09-04). Retrieved on 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Kris Bigalk. "Rare Forms of Twinning". bellaonline.com. Retrieved on 2007-03-22.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bortolus, Renata; Fabio Parazzini, Liliane Chatenoud, Guido Benzi, Massimiliano Maria Bianchi, Alberto Marini (1999). "The epidemiology of multiple births". Human Reproduction Update (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology) 5 (2): 179–187. doi:. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 10336022.

- ↑ LiveScience (2008-02-21). "'Identical' twins? Not according to their DNA", MSNBC. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ↑ April Holladay (2001-05-09). "What triggers twinning?". WonderQuest. Retrieved on 2007-03-22.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Curran, Mark (2005-11-02). "Twinning". Focus Information Technology. Retrieved on 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Benirschke, Kurt (2004). "Multiple Gestation". in Robert Resnik, Robert K. Creasy and Jay D. Iams. Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice (5th ed ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company. pp. 55–62. ISBN 0-7216-0004-2.

- ↑ Edwards, JH; T Dent and J Kahn (June 1966). "Monozygotic twins of different sex". Journal of Medical Genetics 3 (2): 117–123. PMID 6007033.

- ↑ Machin, GA (January 1996). "Some causes of genotypic and phenotypic discordance in monozygotic twin pairs". American Journal of Medical Genetics 61 (3): 216–228. doi:. PMID 8741866.

- ↑ Oleszczuk, Jaroslaw J.; Donald M. Keith, Louis G. Keith and William F. Rayburn (November 1999). "Projections of population-based twinning rates through the year 2100". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine 44 (11): 913–921. PMID 10589400. http://www.reproductivemedicine.com/toc/auto_abstract.php?id=13594. Retrieved on 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Fraga, Mario F.; Esteban Ballestar, Maria F. Paz, Santiago Ropero, Fernando Setien, Maria L. Ballestar†, Damia Heine-Suñer, Juan C. Cigudosa, Miguel Urioste, Javier Benitez, Manuel Boix-Chornet, Abel Sanchez-Aguilera, Charlotte Ling, Emma Carlsson, Pernille Poulsen, Allan Vaag, Zarko Stephan, Tim D. Spector, Yue-Zhong Wu, Christoph Plass and Manel Esteller (July 2005). "Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (30): 10604–9. doi:. PMID 16009939. PMC: 1174919. http://www.pnas.org/content/102/30/10604.full. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ Segal, Nancy L. (1999). Entwined lives: twins and what they tell us about human behavior. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-94465-6. OCLC 40396458.

- ↑ Plomin, Robert (2001). Behavioral genetics. New York: Worth Pubs. ISBN 0-7167-5159-3. OCLC 43894450.

- ↑ Cheng, Maria; Associated Press (2007-07-03). "Study: Twins form after embryo collapses", USA Today. Retrieved on 2008-09-30.

- ↑ European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (2007-07-02). "Time-lapse recordings reveal why IVF embryos are more likely to develop into twins. Researchers believe the laboratory culture could be the cause". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-09-30.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Steinman, Gary (May 2006). "Mechanisms of twinning: VII. Effect of diet and heredity on the human twinning rate". J Reprod Med 51 (5): 405–410. PMID 16779988. http://www.reproductivemedicine.com/toc/auto_abstract.php?id=22626. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ Martin, Joyce A; Melissa M. Park (1999-09-14). "Trends in Twin and Triplet Births: 1980–97" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports (National Center for Health Statistics) 47 (24): 1–17. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr47/nvs47_24.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ Asch, Richard H.; John Studd (1995). Progress in Reproductive Medicine Volume II. Informa. ISBN 1-85070-574-7. OCLC 36287045.

- ↑ Matte, U; MG Le Roux, B Bénichou, JP Moisan and R Giugliani (1996). "Study on possible increase in twinning rate at a small village in south Brazil". Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 45 (4): 431–437. PMID 9181177.

- ↑ Rehan, N; DS Tafida (November 1980). "Multiple births in Hausa women". Br J Obstet Gynaecol 87 (11): 997–1004. doi:. PMID 7437372.

- ↑ Gedda, Luigi (1995). "The role of research in twin medicine". in Louis G. Keith, Emile Papiernik, Donald M. Keith and Barbara Luke. Multiple Pregnancy: Epidemiology, Gestation & Perinatal Outcome. Taylor and Francis. pp. 4. ISBN 1-85070-666-2.

- ↑ Lovell, Tammy (2008-07-17). "Pictured: Proud parents show off their million-to-one black and white twins", Daily Mail, Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved on 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Schmidt, R; EH Sobel, HM Nitowsky, H Dar and FH Allen Jr (February 1976). "Monozygotic twins discordant for sex". Journal of Medical Genetics 13 (1): 64–68. PMID 944787. PMC: 1013354. http://jmg.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/13/1/64. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ Gilbert, Scott F. (2006). "Non-identical Monozygotic Twins". Developmental biology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-250-X. OCLC 172964621.

- ↑ Souter, Vivienne L.; Melissa A. Parisi, Dale R. Nyholt, Raj P. Kapur, Anjali K. Henders, Kent E. Opheim, Daniel F. Gunther, Michael E. Mitchell, Ian A. Glass and Grant W. Montgomery (April 2007). "A case of true hermaphroditism reveals an unusual mechanism of twinning". Hum. Genet. 121 (2): 179–85. doi:. PMID 17165045.

- ↑ LiveScience Staff (2007-03-26). "Rare Semi-Identical Twins Discovered", Imaginova. Retrieved on 2008-10-01.

- ↑ Whitfield, John (2007). "'Semi-identical' twins discovered". Nature. doi:.

Further reading

- Nieuwint, Aggie; Rieteke Van Zalen-Sprock, Pieter Hummel, Gerard Pals, John Van Vugt, Hans Van Der Harten, Yvonne Heins and Kamlesh Madan (1999). "'Identical' twins with discordant karyotypes". Prenatal Diagnosis 19 (1): 72–6. doi:. PMID 10073913.

- Wenk RE, Houtz T, Brooks M, Chiafari FA (1992). "How frequent is heteropaternal superfecundation?". Acta geneticae medicae et gemellologiae 41 (1): 43–7. PMID 1488855.

- Girela, Eloy; Jose A. Lorente, J. Carlos Alvarez, Maria D. Rodrigo, Miguel Lorente and Enrique Villanueva (1997). "Indisputable double paternity in dizygous twins". Fertility and Sterility 67 (6): 1159–61. doi:. PMID 9176461.

- Shinwell ES, Reichman B, Lerner-Geva L, Boyko V, Blickstein I (September 2007). ""Masculinizing" effect on respiratory morbidity in girls from unlike-sex preterm twins: a possible transchorionic paracrine effect". Pediatrics 120 (3): e447–53. doi:. PMID 17766488. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17766488. Retrieved on 2008-10-06.

- Lummaa V, Pettay JE, Russell AF (June 2007). "Male twins reduce fitness of female co-twins in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (26): 10915–20. doi:. PMID 17576931. PMC: 1904168. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17576931. Retrieved on 2008-10-06.

- Schein, Elyse; Paula Bernstein (2007). Identical Strangers: A Memoir of Twins Separated and Reunited. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6496-1. OCLC 123390922.

- Helle, Samuli; Virpi Lummaa and Jukka Jokela (2004). "Selection for Increased Brood Size in Historical Human Populations" (PDF). Evolution 58: 430–436. doi:. http://www.huli.group.shef.ac.uk/helleevolution2004.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-10-02.

- "TWINS™ Guide to the First Year" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: TWINS™ Magazine (2008). Retrieved on 2008-10-06.

- Samson, Jennifer. "Facts About Multiples: An Encyclopedia of Multiple Birth Records". Retrieved on 2008-10-18.