Turner syndrome

| Turner Syndrome Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

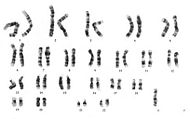

| 45,X. (Note unpaired X at lower right.) | |

| ICD-10 | Q96. |

| ICD-9 | 758.6 |

| DiseasesDB | 13461 |

| MedlinePlus | 000379 |

| eMedicine | ped/2330 |

| MeSH | D014424 |

Turner syndrome or Ullrich-Turner syndrome encompasses several conditions, of which monosomy X is most common. It is a chromosomal disorder affecting females in which all or part of one of the X chromosomes is absent. Occurring in 1 out of every 2500 girls, the syndrome manifests itself in a number of ways. There are characteristic physical abnormalities, such as short stature, lymphoedema, broad chest, low hairline, low-set ears, and webbed neck. Girls with TS typically experience gonadal dysfunction with subsequent amenorrhea and infertility. Concurrent health concerns are also frequently present, including congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, ophthalmological problems, and otological concerns [1]. Finally, a specific pattern of cognitive deficits is often observed, with particular difficulties in visuospatial, mathematic, and memory areas [2].

Contents |

Symptoms

Common symptoms of Turner syndrome include:

- Short stature

- Lymphedema (swelling) of the hands and feet

- Broad chest (shield chest) and widely-spaced nipples

- Low hairline

- Low-set ears

- Reproductive sterility

- Rudimentary ovaries gonadal streak (underdeveloped gonadal structures)

- Amenorrhea, or the absence of a menstrual period

- Increased weight, obesity

- Shield shaped thorax of heart

- Shortened metacarpal IV (of hand)

- Small fingernails

- Characteristic facial features

- Webbing of the neck (webbed neck)

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Poor breast development

- Horseshoe kidney

- Visual impairments sclera, cornea, Glaucoma, etc.

- Ear infections and hearing loss.

Other symptoms may include a small lower jaw (micrognathia), cubitus valgus (turned-out elbows), soft upturned nails, palmar crease and drooping eyelids. Less common are pigmented moles, hearing loss, and a high-arch palate (narrow maxilla). Turner syndrome manifests itself differently in each female affected by the condition, and no two individuals will share the same symptoms.

Risk factors

Risk factors for Turner syndrome are not well known. Nondisjunctions increase with maternal age, such as for Down syndrome, but that effect is not clear for Turner syndrome. It is also unknown if there is a genetic predisposition present that causes the abnormality, though most researchers and doctors treating Turners women agree that this is highly unlikely. There is currently no known cause for Turner syndrome, though there are several theories surrounding the subject.

Incidence

Approximately 98% of all fetuses with Turner syndrome result in miscarriage. Turner syndrome accounts for about 10% of the total number of spontaneous abortions in the United States. The incidence of Turner syndrome in live female births is believed to be 1 in 2500.

History

The syndrome is named after Henry Turner, an Oklahoma endocrinologist, who described it in 1938.[3] In Europe, it is often called Ullrich-Turner syndrome or even Bonnevie-Ullrich-Turner syndrome to acknowledge that earlier cases had also been described by European doctors. The first published report of a female with a 45,X karyotype was in 1959 by Dr. Charles Ford and colleagues in Harwell, Oxfordshire and Guy's Hospital in London.[4] It was found in a 14-year-old girl with signs of Turner syndrome.

Diagnosis

Turner syndrome may be diagnosed by amniocentesis during pregnancy. Sometimes, fetuses with Turner syndrome are identified by abnormal ultrasound findings (i.e. heart defect, kidney abnormality, cystic hygroma, ascites). Although the recurrence risk is not increased, genetic counseling is often recommended for families who have had a pregnancy or child with Turner syndrome.

A test, called a karyotype, analyzes the chromosomal composition of the individual. This is the test of choice to diagnose Turner syndrome.

Prognosis

While most of the physical findings in Turner syndrome are harmless, there can be significant medical problems associated with the syndrome.

Cardiovascular

Price et al. (1986 study of 156 female patients with Turner syndrome) showed a significantly greater number of deaths from diseases of the circulatory system than expected, half of them due to congenital heart disease--mostly postductal coarctation of the aorta. When patients with congenital heart disease were omitted from the sample of the study, the mortality from circulatory disorders was not significantly increased.

Cardiovascular malformations are a serious concern as it is the most common cause of death in adults with Turner syndrome. It takes an important part in the 3-fold increase in overall mortality and the reduced life expectancy (up to 13 years) associated with Turner syndrome.

Cause

According to Sybert, 1998 the data is inadequate to allow conclusions about phenotype-karyotype correlations in regard to cardiovascular malformations in Turner syndrome because the number of individuals studied within the less common karyotype groups is too small. Other studies also suggest the presence of hidden mosaicisms that are not diagnosed on usual karyotypic analyses in some patients with 45,X karyotype.

In conclusion, the associations between karyotype and phenotypic characteristics, including cardiovascular malformations, remain questionable.

Prevalence of cardiovascular malformations

The prevalence of cardiovascular malformations among patients with Turner syndrome ranges from 17% (Landin-Wilhelmsen et al, 2001) to 45% (Dawson-Falk et al, 1992).

The variations found in the different studies are mainly attributable to variations in non-invasive methods used for screening and the types of lesions that they can characterize (Ho et al, 2004). However Sybert, 1998 suggests that it could be simply attributable to the small number of subjects in most studies.

Different karyotypes may have differing prevalence of cardiovascular malformations. Two studies found a prevalence of cardiovascular malformations of 30% (Mazanti et al, 1998 …594 patients with Turner syndrome) and 38% (Gotzsche et al, 1994 …393 patients with Turner syndrome) in a group of pure 45,X monosomy. But considering other karyotype groups, they reported a prevalence of 24.3% (Mazanti et al, 1998) and 11% (Gotzsche et al, 1994) in patients with mosaic X monosomy , and Mazanti et al, 1998 found a prevalence of 11% in patients with X chromosomal structural abnormalities.

The higher prevalence in the group of pure 45,X monosomy is primarily due to a significant difference in the prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities and aortic coarctation, the two most common cardiovascular malformations.

Congenital heart disease

The most commonly observed are congenital obstructive lesions of the left side of the heart, leading to reduced flow on this side of the heart. This includes bicuspid aortic valve and coarctation of the aorta. Sybert, 1998 found that more than 50% of the cardiovascular malformations observed in her study of individuals with Turner syndrome were bicuspid aortic valves or coarctation of the aorta, alone or in combination.

Other congenital cardiovascular malformations such partial anomalous venous drainage and aortic stenosis or aortic regurgitation are also more common in Turner syndrome than in the general population. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome represents the most severe reduction in left-sided structures.

Bicuspid aortic valve. Up to 15% of adults with Turner syndrome have bicuspid aortic valves, meaning that there are only two, instead of three, parts to the valves in the main blood vessel leading from the heart. Since bicuspid valves are capable of regulating blood flow properly, this condition may go undetected without regular screening. However, bicuspid valves are more likely to deteriorate and later fail. Calcification also occurs in the valves,[5] which may lead to a progressive valvular dysfunction as evidenced by aortic stenosis or regurgitation (Elsheikh et al, 2002).

With a prevalence from 12.5% (Mazanti et al, 1998) to 17.5% (Dawson-Falk et al, 1992), Bicuspid aortic valve is the most common congenital malformation affecting the heart in this syndrome. It is usually isolated but it may be seen in combination with other anomalies, particularly coarctation of the aorta.

Coarctation of the aorta. Between 5% and 10% of those born with Turner syndrome have coarctation of the aorta, a congenital narrowing of the descending aorta, usually just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery and opposite to the duct (and so termed “juxtaductal”). Estimates of the prevalence of this malformation in patients with Turner syndrome ranges from 6.9% (Mazanti et al, 1998) to 12.5% (Dawson-Falk et al, 1992). A coarctation of the aorta in a female is suggestive of Turner syndrome, and suggests the need for further tests, such as a karyotype.

Partial anomalous venous drainage. This abnormality is a relatively rare congenital heart disease in the general population. The prevalence of this abnormality also is low (around 2.9%) in Turner syndrome. However, its relative risk is 320 in comparison with the general population. Strangely, Turner syndrome seems to be associated with quite unusual forms of partial anomalous venous drainage. (Mazanti et al, 1998 and Prandstraller et al, 1999)

In the management of a patient with Turner syndrome it is essential to keep in mind that these left-sided cardiovascular malformations in Turner syndrome result in an increased susceptibility to bacterial endocarditis. Therefore prophylactic antibiotics should be considered when procedures with high risk endocarditis are performed, such as dental cleaning (Elsheikh et al, 2002).

Turner syndrome is often associated with persistent hypertension, sometimes in childhood. In the majority of Turner syndrome patients with hypertension, there is no specific cause. In the remainder, it is usually associated with cardiovascular or kidney abnormalities, including coarctation of the aorta.

Aortic dilation, dissection and rupture

Two studies have suggested aortic dilatation in Turner syndrome, typically involving the root of the ascending aorta and occasionally extending through the aortic arch to the descending aorta, or at the site of previous coarctation of the aorta repair (Lin et al, 1998).

- Allen et al, 1986 who evaluated 28 girls with Turner syndrome, found a significantly greater mean aortic root diameter in patients with Turner syndrome than in the control group (matched for body surface area). Nonetheless, the aortic root diameter found in Turner syndrome patients were still well within the limits.

- This has been confirmed by the study of Dawson-Falk et al, 1992 who evaluated 40 patients with Turner syndrome. They presented basically the same findings: a greater mean aortic root diameter, which nevertheless remains within the normal range for body surface area.

Sybert, 1998 points out that it remains unproven that aortic root diameters that are relatively large for body surface area but still well within normal limits imply a risk for progressive dilatation.

- Prevalence of aortic abnormalities

The prevalence of aortic root dilatation ranges from 8.8% (Lin et al, 1986) to 42% (Elsheikh et al, 2001) in patients with Turner syndrome.

Even if not every aortic root dilatation necessarily goes on to an aortic dissection (circumferential or transverse tear of the intima), complications such as dissection, aortic rupture resulting in death may occur. The natural history of aortic root dilatation is still unknown, but it is a fact that it is linked to aortic dissection and rupture, which has a high mortality rate.[6]

Aortic dissection affects 1% to 2% of patients with Turner syndrome.

As a result any aortic root dilatation should be seriously taken into account as it could become a fatal aortic dissection. Routine surveillance is highly recommended (Elsheikh et al, 2002).

- Risk factors for aortic rupture

It is well established that cardiovascular malformations (typically bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of the aorta and some other left-sided cardiac malformations) and hypertension predispose to aortic dilatation and dissection in the general population.

At the same time it has been shown that these risk factors are common in Turner syndrome. Indeed these same risk factors are found in more than 90% of patients with Turner syndrome who develop aortic dilatation. Only a small number of patients (around 10%) have no apparent predisposing risk factors.

It is important to note that the risk of hypertension is increased 3-fold in patients with Turner syndrome. Because of its relation to aortic dissection blood pressure needs to be regularly monitored and hypertension should be treated aggressively with an aim to keep blood pressure below 140/80 mmHg.

It has to be noted that as with the other cardiovascular malformations, complications of aortic dilatation is commonly associated with 45,X karyotype (Elsheikh et al, 2002).

- Pathogenesis of aortic dissection and rupture

The exact role that all these risk factors play in the process leading to such fatal complications is still quite unclear.

Aortic root dilatation is thought to be due to a mesenchymal defect as pathological evidence of cystic medial necrosis has been found by several studies. The association between a similar defect and aortic dilatation is well established in such conditions such as Marfan Syndrome. Also, abnormalities in other mesenchymal tissues (bone matrix and lymphatic vessels) suggests a similar primary mesenchymal defect in patients with Turner syndrome (Lin et al, 1986).

However there is no evidence to suggest that patients with Turner syndrome have a significantly higher risk of aortic dilatation and dissection in absence of predisposing factors. So the risk of aortic dissection in Turner syndrome appears to be a consequence of structural cardiovascular malformations and hemodynamic risk factors rather than a reflection of an inherent abnormality in connective tissue (Sybert, 1998).

The natural history of aortic root dilatation is unknown, but because of its lethal potential, this aortic abnormality needs to be carefully followed.

- Pregnancy

As more women with Turner syndrome complete pregnancy thanks to the new modern techniques to treat infertility, it has to be noted that pregnancy may be a risk of cardiovascular complications for the mother.

Indeed several studies had suggested an increased risk for aortic dissection in pregnancy (Lin et al, 1998). Three deaths have even been reported. The influence of estrogen has been examined but remains unclear. It seems that the high risk of aortic dissection during pregnancy in women with Turner syndrome may be due to the increased hemodynamic load rather than the high estrogen rate (Elsheikh et al, 2002).

Of course these findings are important and need to be remembered while following a pregnant patient with Turner syndrome.

Cardiovascular malformations in Turner syndrome are also very serious, not only because of their high prevalence in that particular population but mainly because of their high lethal potential and their great implication in the increased mortality found in patients with Turner syndrome. Congenital heart disease needs to be explored in every female newly diagnosed with Turner syndrome. As adults are concerned close surveillance of blood pressure is needed to avoid a high risk of fatal complications due to aortic dissection and rupture.

Skeletal

Normal skeletal development is inhibited due to a large variety of factors, mostly hormonal. The average height of a woman with Turner syndrome, in the absence of growth hormone treatment, is 4'7", about 140 cm.

The fourth metacarpal bone (fourth toe and ring finger) may be unusually short, as may the fifth.

Due to inadequate production of estrogen, many of those with Turner syndrome develop osteoporosis. This can decrease height further, as well as exacerbate the curvature of the spine, possibly leading to scoliosis. It is also associated with an increased risk of bone fractures.

Kidney

Approximately one-third of all women with Turner syndrome have one of three kidney abnormalities:

- A single, horseshoe-shaped kidney on one side of the body.

- An abnormal urine-collecting system.

- Poor blood flow to the kidneys.

Some of these conditions can be corrected surgically. Even with these abnormalities, the kidneys of most women with Turner syndrome function normally. However, as noted above, kidney problems may be associated with hypertension.

Thyroid

Approximately one-third of all women with Turner syndrome have a thyroid disorder. Usually it is hypothyroidism, specifically Hashimoto's thyroiditis. If detected, it can be easily treated with thyroid hormone supplements.

Diabetes

Women with Turner syndrome are at a moderately increased risk of developing type 1 diabetes in childhood and a substantially increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes by adult years. The risk of developing type 2 diabetes can be substantially reduced by maintaining a normal weight.

Cognitive

Turner syndrome does not typically cause mental retardation or impair cognition. However, learning difficulties are common among women with Turner syndrome, particularly a specific difficulty in perceiving spatial relationships, such as Nonverbal Learning Disorder. This may also manifest itself as a difficulty with motor control or with mathematics. While it is non-correctable, in most cases it does not cause difficulty in daily living.

There is also a rare variety of Turner Syndrome, known as "Ring-X Turner Syndrome", which has an approximate 60% association with mental retardation. This variety accounts for approximately 2 - 4% of all Turner Syndrome cases.[7]

Reproductive

Women with Turner syndrome are almost universally infertile. While some women with Turner syndrome have successfully become pregnant and carried their pregnancies to term, this is very rare and is generally limited to those women whose karyotypes are not 45,X.[8] Even when such pregnancies do occur, there is a higher than average risk of miscarriage or birth defects, including Turner Syndrome or Down Syndrome.[9] Some women with Turner syndrome who are unable to conceive without medical intervention may be able to use IVF or other fertility treatments.[10]

Usually estrogen replacement therapy is used to spur growth of secondary sexual characteristics at the time when puberty should onset. While very few women with Turner Syndrome menstruate spontaneously, estrogen therapy requires a regular shedding of the uterine lining ("withdrawal bleeding") to prevent its overgrowth. Withdrawal bleeding can be induced monthly, like menstruation, or less often, usually every three months, if the patient desires. Estrogen therapy does not make a woman with nonfunctional ovaries fertile, but it plays an important role in assisted reproduction; the health of the uterus must be maintained with estrogen if an eligible woman with Turner Syndrome wishes to use IVF.

Treatment

As a chromosomal condition, there is no "cure" for Turner syndrome. However, much can be done to minimize the symptoms. For example:[11]

- Growth hormone, either alone or with a low dose of androgen, will increase growth and probably final adult height. Growth hormone is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of Turner syndrome and is covered by many insurance plans.[11][12] There is evidence that this is effective, even in toddlers.[13]

- Estrogen replacement therapy has been used since the condition was described in 1938 to promote development of secondary sexual characteristics. Estrogens are crucial for maintaining good bone integrity and tissue health.[11] Women with Turner Syndrome who do not have spontaneous puberty and who are not treated with estrogen are at high risk for osteoporosis.

- Modern reproductive technologies have also been used to help women with Turner syndrome become pregnant if they desire. For example, a donor egg can be used to create an embryo, which is carried by the Turner syndrome woman.[11] However, in some countries egg donation is illegal.

- Uterine maturity is positively associated with years of estrogen use, history of spontaneous menarche, and negatively associated with the lack of current hormone replacement therapy.[14]

Links

- Bondy CA (2007). "Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: A guideline of the Turner Syndrome Study Group". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92 (1): 10–25. doi:. PMID 17047017.

See also

- Gonadal dysgenesis, for related abnormalities

References

- ↑ Sybert, V.P., McCauley, E. (2004). Turner’s Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 1227-1238.

- ↑ Rovet, J.F. (1993). The psychoeducational characteristics of children with Turner syndrome. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 26, 333-341.

- ↑ Turner HH. (1938). A syndrome of infantilism, congenital webbed neck, and cubitus valgus. Endocrinology. 23:566-574.

- ↑ Ford CE, Jones KW, Polani PE, de Almeida JC, Briggs JH (April 4, 1959). "A sex-chromosome anomaly in a case of gonadal dysgenesis (Turner's syndrome)". Lancet 273 (7075): 711–3. doi:. PMID 13642858. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T1B-49J95GR-DW&_user=10&_coverDate=04%2F04%2F1959&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=853bb25a0b51f31d72fcbbe51ad995ba.

- ↑ Aortic Valve, Bicuspid. Last Updated: June 22, 2006 - Author: Edward J Bayne, MD

- ↑ Surgical treatment of the aortic root dilatation - Concha Ruiz M.

- ↑ Gary Berkovitz, Judith Stamberg, Leslie P. Plotnick and Roberto Lanes (June 1983). "Turner syndrome patients with a ring X chromosome". Clinical Genetics 23 (6): 447–453. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1983.tb01980.x (inactive 2008-06-25). http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1399-0004.1983.tb01980.x?journalCode=cge.

- ↑ Kaneko N, Kawagoe S, Hiroi M (1990). "Turner's syndrome--review of the literature with reference to a successful pregnancy outcome". Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 29 (2): 81–7. PMID 2185981.

- ↑ Nielsen J, Sillesen I, Hansen KB (1979). "Fertility in women with Turner's syndrome. Case report and review of literature". British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 86 (11): 833–5. PMID 508669.

- ↑ Hovatta O (1999). "Pregnancies in women with Turner's syndrome". Ann. Med. 31 (2): 106–10. PMID 10344582.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Turner Syndrome Society of the United States. "FAQ 6. What can be done?". Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ↑ Bolar K, Hoffman AR, Maneatis T, Lippe B (2008). "Long-term safety of recombinant human growth hormone in Turner syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93 (2): 344–51. doi:. PMID 18000090.

- ↑ Davenport ML, Crowe BJ, Travers SH, et al (2007). "Growth hormone treatment of early growth failure in toddlers with Turner syndrome: a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92 (9): 3406–16. doi:. PMID 17595258.

- ↑ "Uterine Development in Turner Syndrome". GGH Journal 24 (1). 2008. ISSN 1932-9032. http://gghjournal.com/volume24/1/ab12.cfm.

See also

- Other human sex chromosome aneuploids:

- Dermatoglyphics

- Noonan syndrome, a disorder which is often confused with Turner syndrome because of several physical features that they have in common.

External links

- Stanford University Turner Syndrome Research

- Turner Syndrome at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- Recent research in Turner Syndrome

- Noonan Syndrome (Turner syndrome with normal Karyotype) at OMIM

- Genetic and Rare Disease Information Center (NIH) Has several US government links to Turner syndrome.

- Medical Encyclopedia

- The MAGIC Foundation for Children's Growth

- Turner Syndrome Society of the United States

- Turner Syndrome Support Society (United Kingdom)

- Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||