Treaty of Versailles

| Treaty of Versailles | |

|---|---|

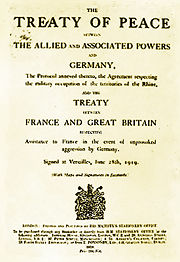

| Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany | |

Front page of the version in English

|

|

| Signed - location |

28 June 1919 Versailles, France |

| Effective - condition |

10 January 1920 Ratification by Germany and three Principal Allied Powers. |

| Signatories | Other Allied Powers

|

| Depositary | French Government |

| Languages | French, English |

| Wikisource original text: Treaty of Versailles |

|

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, one of the events that triggered the start of the war. Although the armistice signed on 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. Of the many provisions in the treaty, one of the most important and controversial required Germany and its allies to accept responsibility for causing the war and, under the terms of articles 231-248, to disarm, make substantial territorial concessions and pay reparations to certain countries that had formed the Entente powers. The Treaty was undermined by subsequent events starting as early as 1922 and was widely flouted by the mid-thirties.[1]

The result of these competing and sometimes incompatible goals among the victors was a compromise that nobody was satisfied with. Germany was neither pacified nor conciliated, which would prove to be a factor leading to later conflicts.[2]

Contents |

Negotiations

Negotiations between the Allied powers started on 18 January in the Salle de l'Horloge at the French Foreign Ministry, on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris. Initially, 70 delegates of 27 nations participated in the negotiations.[3] Having been defeated, Germany, Austria, and Hungary were excluded from the negotiations. Russia was also excluded because it had negotiated a separate peace with Germany in 1917, in which Germany gained a large fraction of Russia's land and resources.

Until March 1919, the most important role for negotiating the extremely complex and difficult terms of the peace fell to the regular meetings of the "Council of Ten" (leaders of government and foreign ministers) composed of the five major victors (the United States, France, Great Britain, Italy, and Japan). As this unusual body proved too unwieldy and formal for effective decision-making, Japan and - for most of the remaining conference - the foreign ministers left the main meetings, so that only the "Big Four" remained.[4] After his territorial claims to Fiume were rejected, Italian Prime Minister, Vittorio Orlando left the negotiations (only to return to sign in June), and the final conditions were determined by the leaders of the "Big Three" nations: British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, and American President Woodrow Wilson.

Japan had originally attempted to insert a clause proscribing discrimination on the basis of race or nationality, but this was eventually struck down due to prevailing racist attitudes, in particular in Australia.[5]

At Versailles, it was difficult to decide on a common position because their aims conflicted with one another. The result has been called the "unhappy compromise".[6]

France's aims

- Further information: Revanchism

France had lost some 1.5 million military personnel and an estimated 400,000 civilians to the war (see World War I casualties), and much of the western front had been fought on French soil. To appease the French public, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau wanted to impose policies deliberately meant to cripple Germany militarily, politically, and economically so as never to be able to invade France again. Georges Clemenceau also particularly wished to regain the rich and industrial land of Alsace-Lorraine, which had been stripped from France by Germany in the 1871 War.

Britain's aims

Prime Minister David Lloyd George supported reparations but to a lesser extent than the French. Lloyd George was aware that if the demands made by France were carried out, France could become the most powerful force on the continent, and a delicate balance could be unsettled. Lloyd George was also worried by Woodrow Wilson's proposal for "self-determination" and, like the French, wanted to preserve his own nation's empire. Like the French, Lloyd George also supported secret treaties and naval blockades.

Prior to the war, Germany had been Britain's main competitor and its largest trading partner,[7] making the destruction of Germany at best a mixed blessing.

Lloyd George managed to increase the overall reparations payment and Britain's share by demanding compensation for the huge number of widows, orphans, and men left unable to work through injury, due to the war.

United States' aims

There had been strong non-interventionist sentiment before and after the United States entered the war in April 1917, and many Americans felt eager to extricate themselves from European affairs as rapidly as possible. The United States took a more conciliatory view toward the issue of German reparations. American Leaders wanted to ensure the success of future trading opportunities and favourably collect on the European debt, and hoped to avoid future wars.

Before the end of the war, President Woodrow Wilson, along with other American officials including Edward Mandell House, put forward his Fourteen Points which he presented in a speech at the Paris Peace Conference.

Content

Impositions on Germany

Legal restrictions

- Article 231 (the "War Guilt Clause") lays sole responsibility for the war on Germany, which would be accountable for all the damage done to civilian population of the allies.

- Article 227 charges former German Emperor, Wilhelm II with supreme offence against international morality. He is to be tried as a war criminal.

- Articles 228-230 tried many other Germans as war criminals.

Military restrictions

Part V of the treaty begins with the preamble, "In order to render possible the initiation of a general limitation of the armaments of all nations, Germany undertakes strictly to observe the military, naval and air clauses which follow."[8]

- The Rhineland will become a demilitarised zone.

- German armed forces will number no more than 100,000 troops, and conscription will be abolished.

- Enlisted men will be retained for at least 12 years; officers to be retained for at least 25 years.

- German naval forces will be limited to 15,000 men, 6 battleships (no more than 10,000 tons displacement each), 6 cruisers (no more than 6,000 tons displacement each), 12 destroyers (no more than 800 tons displacement each) and 12 torpedo boats (no more than 200 tons displacement each).

- The manufacture, import, and export of weapons and poison gas is prohibited.

- Tanks, submarines, military aircraft, and artillery are prohibited.

- Blockades on ports are prohibited.

Territorial losses

Germany was compelled to yield control of its colonies, and would also lose a number of European territories. Most notably, the province of West Prussia would be ceded to the newly independent Second Polish Republic, thereby granting Poland access to the Baltic Sea via the "Polish Corridor", and turning East Prussia into an exclave, separated from mainland Germany.

- Alsace-Lorraine, the territories which were ceded to Germany in accordance with the Preliminaries of Peace signed at Versailles on 26 February 1871, and the Treaty of Frankfurt of 10 May 1871, were restored to French sovereignty without a plebiscite as from the date of the Armistice of 11 November 1918. (area 14,522 km², 1,815,000 inhabitants (1905)). Clemenceau was convinced that the German neighbour had "20 million people too much", thus incorporating the seven million inhabitants and the industry of the Prussian province was seen as means to weaken Germany and strengthen France.[9]

- Northern Schleswig was returned to Denmark following a plebiscite on 14 February 1920 (area 3,984 km², 163,600 inhabitants (1920)). Central Schleswig, including the city of Flensburg, opted to remain German in a separate referendum on 14 March 1920.

- Most of the Prussian provinces of Posen and of West Prussia, which Prussia had annexed in Partitions of Poland (1772-1795), were ceded to Poland (area 53,800 km², 4,224,000 inhabitants (1931), including 510 km² and 26,000 inhabitants from Upper Silesia). Most of the Province of Posen had already come under Polish control during the Great Poland Uprising of 1918-1919.

- The Hlučínsko (Hultschin) area of Upper Silesia to Czechoslovakia (area 316 or 333 km², 49,000 inhabitants) without a plebiscite.

- The eastern part of Upper Silesia to Poland (area 3,214,km², 965,000 inhabitants), after the plebiscite for the whole of Upper Silesia, which was provided for in the Treaty, and the ensuing partition along voting lines in Upper Silesia by the League of Nations following protests by the Polish inhabitants.

- The area of cities Eupen and Malmedy to Belgium. The trackbed of the Vennbahn railway also transferred to Belgium.

- The area of Soldau in East Prussia (railway station on the Warsaw-Danzig route) to Poland (area 492 km²).

- The northern part of East Prussia known as Memel Territory under control of France, later occupied by Lithuania.

- From the eastern part of West Prussia and the southern part of East Prussia, after the East Prussian plebiscite a small area to Poland.

- The province of Saarland to be under the control of the League of Nations for 15 years, after that a plebiscite between France and Germany, to decide to which country it would belong. During this time, coal would be sent to France.

- The port of Danzig with the delta of the Vistula River at the Baltic Sea was made the Freie Stadt Danzig (Free City of Danzig) under the permanent governance of the League of Nations without a plebiscite (area 1,893 km², 408,000 inhabitants (1929)).

- The German and Austrian governments had to acknowledge and strictly respect the independence of Austria. The unification of both countries, although desired by the huge majority of both populations, was strictly forbidden.[10][11]

Shandong problem

Article 156 of the treaty transferred German concessions in Shandong, China to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China. Chinese outrage over this provision led to demonstrations and a cultural movement known as the May Fourth Movement and influenced China not to sign the treaty. China declared the end of its war against Germany in September 1919 and signed a separate treaty with Germany in 1921.

Reparations

Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles assigned blame for the war to Germany; much of the rest of the Treaty set out the reparations that Germany would pay to the Allies.

The total sum of war reparations demanded from Germany — 226 billion Reichsmarks in gold (around £11.3 billion)— was decided by an Inter-Allied Reparations Commission. In 1921, it was reduced to 132 billion Reichsmarks (£4.99 billion). Timothy W. Guinnane (January 2004). "Vergangenheitsbewältigung: the 1953 London Debt Agreement]". Center Discussion Paper no. 880. Economic Growth Center, Yale University. Retrieved on 2008-12-06. </ref>

The Versailles reparation impositions were partly a reply to the reparations placed upon France by Germany through the 1871 Treaty of Frankfurt signed after the Franco-Prussian War. However, critics of the Treaty argued that France had been able to pay the reparations (5 billion Francs) within 3 years while the Young Plan of 1929 estimated German reparations to be paid until 1988. Indemnities of the Treaty of Frankfurt were in turn calculated, on the basis of population, as the precise equivalent of the indemnities imposed by Napoleon I on Prussia in 1807.[12]

The Versailles Reparations came in a variety of forms, including coal, steel, intellectual property (eg. the patent for Aspirin) and agricultural products, in no small part because currency reparations of that order of magnitude would lead to hyperinflation, as actually occurred in postwar Germany (see 1920s German inflation), thus decreasing the benefits to France and the United Kingdom.

Germany will finish paying off her World War I reparations in 2020.[13]

The creation of international organisations

Part I of the treaty was the Covenant of the League of Nations which provided for the creation of the League of Nations, an organisation intended to arbitrate international disputes and thereby avoid future wars.[14]. Part XIII organised the establishment of the International Labour Organisation, to promote "the regulation of the hours of work, including the establishment of a maximum working day and week, the regulation of the labour supply, the prevention of unemployment, the provision of an adequate living wage, the protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment, the protection of children, young persons and women, provision for old age and injury, protection of the interests of workers when employed in countries other than their own recognition of the principle of freedom of association, the organisation of vocational and technical education and other measures"[15] Further international commissions were to be set up, according to Part XII, to administer control over the Elbe, the Oder, the Niemen (Russstrom-Memel-Niemen) and the Danube rivers.[16]

Other

The Treaty contained a lot of other provisions (economic issues, transportation, etc.). One of the provisions was the following:

- "ARTICLE 246. Within six months from the coming into force of the present Treaty, ... Germany will hand over to His Britannic Majesty's Government the skull of the Sultan Mkwawa which was removed from the Protectorate of German East Africa and taken to Germany."

Reactions

Among the allies

Clemenceau had failed to achieve all of the demands of the French people, and he was voted out of office in the elections of January 1920. French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who felt the restrictions on Germany were too lenient, declared, "This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years."[17]

Influenced by the opposition of Henry Cabot Lodge, the United States Senate voted against ratifying the treaty. Despite considerable debate, Wilson refused to support the treaty with any of the reservations imposed by the Senate.[18] As a result, the United States did not join the League of Nations, despite Wilson's claims that he could "predict with absolute certainty that within another generation there will be another world war if the nations of the world do not concert the method by which to prevent it."[19]

Wilson's friend Edward Mandell House, present at the negotiations, wrote in his diary on 29 June 1919:

"I am leaving Paris, after eight fateful months, with conflicting emotions. Looking at the conference in retrospect, there is much to approve and yet much to regret. It is easy to say what should have been done, but more difficult to have found a way of doing it. To those who are saying that the treaty is bad and should never have been made and that it will involve Europe in infinite difficulties in its enforcement, I feel like admitting it. But I would also say in reply that empires cannot be shattered, and new states raised upon their ruins without disturbance. To create new boundaries is to create new troubles. The one follows the other. While I should have preferred a different peace, I doubt very much whether it could have been made, for the ingredients required for such a peace as I would have were lacking at Paris."[20]

After Wilson's successor Warren G. Harding continued American opposition to the League of Nations, Congress passed the Knox-Porter Resolution bringing a formal end to hostilities between the United States and the Central Powers. It was signed into law by Harding on 21 July 1921.[21]

In Germany

- See also: Stab-in-the-back legend

On 29 April the German delegation under the leadership of the Foreign Minister Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau arrived in Versailles. On 7 May when faced with the conditions dictated by the victors, including the so-called "War Guilt Clause", Foreign Minister Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau replied to Clemenceau, Wilson and Lloyd George: We know the full brunt of hate that confronts us here. You demand from us to confess we were the only guilty party of war; such a confession in my mouth would be a lie.[22]

Because Germany was not allowed to take part in the negotiations, the German government issued a protest against what it considered to be unfair demands, and a "violation of honour"[23] and soon afterwards, withdrew from the proceedings of the Treaty of Versailles. Germany's first democratically elected Chancellor, Philipp Scheidemann refused to sign the treaty and resigned. In a passionate speech before the National Assembly on 12 March 1919, he called the treaty a "murderous plan" and exclaimed,

Which hand, trying to put us in chains like these, would not wither? The treaty is unacceptable. [24]

After Scheidemann's resignation, a new coalition government was formed under Gustav Bauer and it recommended signing the treaty. The National Assembly voted in favour of signing the treaty by 237 to 138, with 5 abstentions. The foreign minister Hermann Müller and Johannes Bell travelled to Versailles to sign the treaty on behalf of Germany. The treaty was signed on 28 June 1919 and ratified by the National Assembly on 9 July 1919 by a vote of 209 to 116.[25]

Conservatives, nationalists and ex-military leaders began to speak critically about the peace and Weimar politicians, socialists, communists, and Jews were viewed with suspicion due to their supposed extra-national loyalties. It was rumoured that the Jews had not supported the war and had played a role in selling out Germany to its enemies. This was mainly due to certain members of the World Zionist Congress, many of whom were from Germany, attempting to influence (with some success) the British and American governments' policy toward the Ottoman Empire (with special attention given to the fate of Palestine), which became known at the Paris Peace Conference. This effort produced the Balfour Declaration.[26] These November Criminals, or those who seemed to benefit from a weakened Germany, and the newly formed Weimar Republic, were seen to have "stabbed them in the back" on the home front, by either criticizing German nationalism, instigating unrest and strikes in the critical military industries or profiteering. These theories were given credence by the fact that when Germany surrendered in November 1918, its armies were still in French and Belgian territory. Not only had the German Army been in enemy territory the entire time on the Western Front, but on the Eastern Front, Germany had already won the war against Russia, concluded with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. In the West, Germany had seemed to come close to winning the war with the Spring Offensive. Its failure was blamed on strikes in the arms industry at a critical moment of the offensive, leaving soldiers with an inadequate supply of materiel. The strikes were seen to be instigated by treasonous elements, with the Jews taking most of the blame. This overlooked Germany's strategic position and ignored how the efforts of individuals were somewhat marginalized on the front.

Nevertheless, this myth of domestic betrayal fell on fertile ground, due to the conditions of the treaty seen unanimously seen as unacceptable (quote Philip Scheidemann before he refused to sign and stepped down) [27] by all political parties from left to right.

Violations

The German economy was so weak that only a small percentage of reparations was paid in hard currency. Nonetheless, even the payment of this small percentage of the original reparations (219 billion Gold Reichsmarks) still placed a significant burden on the German economy, accounting for as much as one third of post-treaty hyperinflation. The economic strain eventually reached the point where Germany stopped paying the reparations 'agreed' upon in the Treaty of Versailles. As a result French and Belgium forces invaded and occupied the Ruhr, a heavily industrialised part of Germany along the French-German border. German workers called a 'passive resistance', meaning that they would no longer work the factories while the French owned them.

Some significant violations (or avoidances) of the provisions of the Treaty were:

- In 1919 the dissolution of the General Staff appeared to happen; however, the core of the General Staff was hidden within another organization, the Truppenamt, where it rewrote all Heer (Army) and Luftstreitkräfte (Air Force) doctrinal and training materials based on the experience of World War I.

- On 16th April, 1922, representatives of the governments of Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Rapallo Treaty at a World Economic Conference at Genoa in Italy. The treaty re-established diplomatic relations, renounced financial claims on each other and pledged future cooperation.

- In 1932 the German government announced it would no longer adhere to the treaty´s military limitations, citing the Allies violation of the treaty by failing to initiate military limitations on themselves as called for in the preamble of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles.

- In March 1935, Adolf Hitler violated the Treaty of Versailles by introducing compulsory military conscription in Germany and rebuilding the armed forces. This included a new Navy (Kriegsmarine), the first full armoured divisions (Panzerwaffe) and an Air Force (Luftwaffe).

- In June 1935 the United Kingdom effectively withdrew from the Treaty with the signing of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement.

- In March 1936, Hitler violated the Treaty by reoccupying the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland.

- In March 1938, Hitler violated the Treaty by annexing Austria in the Anschluss.

- In September 1938, Hitler with approval of France, Britain and Italy violated the Treaty by annexing Czechoslovak border regions, the so-called Sudetenland

- In March 1939, Hitler violated the Treaty by occupying the rest of Czechoslovakia.

- On September 1, 1939, Hitler violated the Treaty by invading Poland, thus initiating World War II in Europe.

Historical assessments

Henry Kissinger called the treaty a "brittle compromise agreement between American utopianism and European paranoia — too conditional to fulfil the dreams of the former, too tentative to alleviate the fears of the latter."

In his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Keynes referred to the Treaty of Versailles as a "Carthaginian peace".[28] Keynes had been the principal representative of the British Treasury at the Paris Peace Conference, and used in his passionate book arguments which he and others (including some US officials) had used at Paris.[29]

French Resistance economist Étienne Mantoux disputed that analysis. During the 1940s, Mantoux wrote a book titled, "The Carthaginian Peace, or the Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes" in an attempt to rebut Keynes' claims; it was published after his death.

More recently it has been argued (for instance by historian Gerhard Weinberg in his book "A World At Arms"[30]) that the treaty was in fact quite advantageous to Germany. The Bismarckian Reich was maintained as a political unit instead of being broken up, and Germany largely escaped post-war military occupation (in contrast to the situation following World War II.)

The British military historian Correlli Barnett claimed that the Treaty of Versailles was "extremely lenient in comparison with the peace terms Germany herself, when she was expecting to win the war, had had in mind to impose on the Allies". Furthermore, he claimed, it was "hardly a slap on the wrist" when contrasted with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that Germany had imposed on a defeated Russia in March 1918, which had taken away a third of Russia's population (albeit of non-Russian ethnicity), one half of Russia's industrial undertakings and nine-tenths of Russia's coal mines, coupled with an indemnity of six billion marks.[31]

Barnett also claims that, in strategic terms, Germany was in fact in a superior position following the Treaty than she had been in 1914. Germany's eastern frontiers faced Russia and Austria, who had both in the past balanced German power. But Barnett asserts that, because the Austrian empire fractured after the war into smaller, weaker states and Russia was wracked by revolution and civil war, the newly restored Poland was no match for even a defeated Germany.

In the West, Germany was balanced only by France and Belgium, both of which were smaller in population and less economically vibrant than Germany. Barnett concludes by saying that instead of weakening Germany, the Treaty "much enhanced" German power.[32] Britain and France should have (according to Barnett) "divided and permanently weakened" Germany by undoing Bismarck's work and partitioning Germany into smaller, weaker states so it could never disrupt the peace of Europe again.[33] By failing to do this and therefore not solving the problem of German power and restoring the equilibrium of Europe, Britain "had failed in her main purpose in taking part in the Great War".[34]

Regardless of modern strategic or economic analysis, resentment caused by the treaty sowed fertile psychological ground for the eventual rise of the Nazi party. Indeed, on Nazi Germany's rise to power, Adolf Hitler resolved to overturn the remaining military and territorial provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. Military build-up began almost immediately in direct defiance of the Treaty, which, by then, had been destroyed by Hitler in front of a cheering crowd. "It was this treaty which caused a chain reaction leading to World War II" claimed historian Dan Rowling (1951). Various references to the treaty are found in many of Hitler's speeches and in pre-war Nazi propaganda.

French historian Raymond Cartier points out that millions of Germans in the Sudetenland and in Posen-West Prussia were placed under foreign rule in a hostile environment, where harassment and violation of rights by authorities are documented.[35] Cartier asserts that, out of 1,058,000 Germans in Posen-West Prussia in 1921, 758,867 fled their homelands within five years due to Polish harassment.[35] In 1926, the Polish Ministry of the Interior estimated the remaining number of Germans at less than 300,000. These sharpening ethnic conflicts would lead to public demands of reattaching the annexed territory in 1938 and become a pretext for Hitler's annexations of Czechoslovakia and parts of Poland[35]

The "2008 School Project History" has explored the question of depicting Germany as having "accepted the Versailles Treaty" in many German history textbooks, insofar as this creates the impression that German delegates signed the treaty freely rather than under the threat of renewed (or continued) sanctions[36][37] [38] [39].

See also

- Aftermath of World War I

- Causes of World War II For other related causes of the war

- International Opium Convention, incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles

- Dawes Plan

- Minority Treaties

- Neutrality Acts

- Small Treaty of Versailles

Notes

- ↑ Viault, Birdsall S. (1990). Schaum's Outline of Modern European History. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 471. http://books.google.com/books?id=hXaJLfcIBuoC.

- ↑ The Economic Consequences of the Peace by John Maynard Keynes at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Lentin, Antony (1985). Guilt at Versailles: Lloyd George and the Pre-history of Appeasement. Routledge. pp. 84. ISBN 9780416411300.

- ↑ Alan Sharp, "The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking in Paris, 1919", 1991

- ↑ http://www.zackvision.com/weblog/2003/10/league-of-nations.html http://www.abc.net.au/federation/fedstory/ep2/ep2_places.htm

- ↑ Harold Nicolson, Diaries and Letters, 1930-39,250; quoted in Derek Drinkwater: Sir Harold Nicolson and International Relations: The Practitioner as Theorist, P.139

- ↑ "One has to acknowledge that Germany is, with her ambitious plans for world politics, maritime dominance and military domination, the only disturbing factor". The State Secretary in the London Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sir Charles Hardinge on 30 October 1906.

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part V at Wikisource

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich, Von deutschen Schulden, Berliner Zeitung, 09. October 1999 [1]

- ↑ Rolf Steininger, Die Anschlußbestrebungen Deutschösterreichs und das Deutsche Reich 1918/19, in: Arbeitskreis für regionale Geschichte (Hg.), "Eidgenossen, helft Euren Brüdern in der Not!" Vorarlbergs Beziehungen zu seinen Nachbarstaaten 1918-1922, Feldkirch 1990, 65-83.

- ↑ http://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/artikel/artikel_44926 (German)

- ↑ A.J.P. Taylor, Bismarck The Man and the Statesman. New York: Vintage Books. 1967, p. 133

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich, Von deutschen Schulden, Berliner Zeitung, 09. October 1999 [2]

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part I: Covenant of the League of Nations at Wikisource

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part XIII: Constitution of the International Labour Office at Wikisource

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part XII at Wikisource

- ↑ R. Henig, Versailles and After: 1919 – 1933 (London: Routledge, 1995) p. 52

- ↑ United States Senate: A Bitter Rejection

- ↑ WOODROW WILSON: Appeal for Support of the League of Nations

- ↑ Bibliographical Introduction to "Diary, Reminiscences and Memories of Colonel Edward M. House"

- ↑ Wimer, Kurt; Wimer, Sarah (1967), "The Harding Administration, the League of Nations, and the Separate Peace Treaty", The Review of Politics 29 (1): 13–24, http://www.jstor.org/pss/1405810.

- ↑ Foreign Minister Brockdorff-Ranzau when faced with the conditions on May 7th: "Wir kennen die Wucht des Hasses, die uns hier entgegentritt. Es wird von uns verlangt, daß wir uns als die allein Schuldigen am Krieg bekennen; ein solches Bekenntnis wäre in meinem Munde eine Lüge". 2008 School Projekt Heinrich-Heine-Gesamtschule, Düsseldorf http://www.fkoester.de/kursbuch/unterrichtsmaterial/13_2_74.html

- ↑ 2008 School Projekt Heinrich-Heine-Gesamtschule, Düsseldorf http://www.fkoester.de/kursbuch/unterrichtsmaterial/13_2_74.html

- ↑ Lauteinann, Geschichten in Quellen Bd. 6, S. 129

- ↑ Koppel S. Pinson (1964). Modern Germany: Its History and Civilization (13th printing ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 397 f.

- ↑ T. Segev One Palestine, Complete pp. 33-56 Holt Paperbacks ISBN 0805065873

- ↑ see further above Scheidemann's speech

- ↑ The Economic Consequences of the Peace by John Maynard Keynes at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Markwell, Donald, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace, Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Reynolds, David. (February 20, 1994). "Over There, and There, and There." Review of: "A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II," by Gerhard L. Weinberg. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Pan, 2002), p. 392.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 316.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 318.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 319.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 La Seconde Guerre mondiale, Raymond Cartier, Paris, Larousse Paris Match, 1965, quoted in: Die "Jagd auf Deutsche" im Osten, Die Verfolgung begann nicht erst mit dem "Bromberger Blutsonntag" vor 50 Jahren, by Pater Lothar Groppe, © Preußische Allgemeine Zeitung / 28. August 2004

- ↑ 2008 School Projekt History, Heinrich-Heine-Gesamtschule, Düsseldorf http://www.fkoester.de/kursbuch/unterrichtsmaterial/13_2_74.html

- ↑ New York Times, July 11, 1919, Page 5 http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9406E6D71E3BEE3ABC4952DFB1668382609EDE, see original document: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9406E6D71E3BEE3ABC4952DFB1668382609EDE&oref=slogin

- ↑ Im Endstadium einer auf allen politischen und militärischen Ebenen geführten Diskussion über die Annahme oder Ablehnung der alliierten Friedensbedingungen demissionierte das in dieser Frage unüberbrückbar gespaltene Kabinett Scheidemann in den frühen Morgenstunden des 20. Juni 1919. Weniger als 100 Stunden vor der von den Alliierten für den Fall der Ablehnung angekündigten Wiederaufnahme des Krieges besaß das Deutsche Reich keine handlungswillige Regierung mehr. Bundesarchiv Berlin - Federal German Archives Berlin, Files of the Reich Chancellery, das Kabinett Bauer, Vol. 1, Introduction, Formation of Government and acceptance of the Versailles Treaty, http://www.bundesarchiv.de/aktenreichskanzlei/1919-1933/0000/bau/bau1p/kap1_1/para2_2.html

- ↑ The British naval blockade became a Hungerblockade for the German population: Insgesamt erwies sich die britische Seeblockade dabei als sehr wirksame und dauerhafte Waffe gegen die deutsche Wirtschaft und gegen die notleidende Bevölkerung, für die sie zur "Hungerblockade" wurde. Auch nach dem Waffenstillstand von Compiègne im November 1918 setzten die Briten die Blockade fort, was die Verbitterung in Deutschland noch zusätzlich steigerte. ©2008 DHM Deutsches Historisches Museum - German State Museum of History http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/wk1/kriegsverlauf/seeblockade/index.html

References

- David Andelman. (2007). A Shattered Peace: Versailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today. New York: John Wiley & Sons Publishers. ISBN 978-0-471-78898-0

- Demarco, Neil. (1987). The World This Century: Working with Evidence. Collins Educational. ISBN 0003222179

- MacMillan, Margaret. (2001). Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (also titled Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World and Peacemakers: Six Months That Changed the World). London: John Murray Publishers. ISBN 0-7195-5939-1.

- Nicholson, Harold. (1933) Peacemaking, 1919, Being Reminiscences of the Paris Peace Conference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 1-931541-54-X

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John. (1972).The Wreck of Reparations, being the political background of the Lausanne Agreement, 1932. New York: H. Fertig.

External links

- The consequences of the Treaty of Versailles for today's world

- Peace Treaty?

- Text of Protest by Germany and Acceptance of Fair Peace Treaty

- "Versailles Revisted" (Review of Manfred Boemeke, Gerald Feldman and Elisabeth Glaser, The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years. Cambridge, UK: German History Institute, Washington, and Cambridge University Press, 1998), Strategic Studies 9:2 (Spring 2000), 191-205

- My 1919 - A film from the Chinese point of view, the only country that did not sign the treaty

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||