Transportation in New York City

| Transportation in New York City | |

| Info | |

|---|---|

| Locale | New York City and the surrounding region in New York State, New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania |

| Transit type | Rapid transit, commuter rail, buses, private automobile, ferry, Taxicab, bicycle, pedestrian |

| Daily ridership | More than ten million commuters daily |

| Operation | |

| Owner | Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, local governments, states |

| Operator(s) | Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Long Island Railroad, Port Authority Trans-Hudson, Metro-North Commuter Railroad Company, New Jersey Transit, New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission, New York Waterway, New York Water Taxi, Liberty Water Taxi. |

The transportation system of New York City is a cooperation of complex systems of infrastructure. New York City, being the largest city in the United States, has a transportation system which includes the largest subway system in the world, measured by track mileage; the world's first mechanically ventilated vehicular tunnel, and an aerial tramway. Through prolonged use, and a distinct history of events, the infrastructure now faces increasing problems in functionality, dependability, and funding.

Contents |

Background

History

The history of New York City's transportation system began with the Dutch port of Nieuw Amsterdam. The port had maintained severale roads; some were built atop former Lenape trails, others as "commuter" links to surrounding cities, and one was even paved by 1658 from orders of Petrus Stuyvesant, according to Burrow, et al.[1] The 19th century brought changes to the format of the system's transport- a street grid by 1811 (see the Commissioners' Plan of 1811), as well as an unprecedented link between New York and Brooklyn, then separate cities, via the Brooklyn Bridge, in 1883.

The Second Industrial Revolution fundamentally changed the city – the port infrastructure grew at such a rapid pace after the 1825 completion of the Erie Canal that New York became the most important connection between all of Europe and the interior of the United States. Elevated trains and subterranean transportation ('El trains' and 'subways') were introduced between 1880 and 1904. In 1904, the first subway line became operational.[2] Practical private automobiles brought an additional change for the city by around 1930, notably the 1927 Holland Tunnel. With automobiles gaining importance, the later rise of Robert Moses was essential to creating New York's modern road infrastructure. Moses was the architect of all 416 miles of parkway, many other important roads, and seven great bridges.[3]

Mass Transit Use and Car Ownership

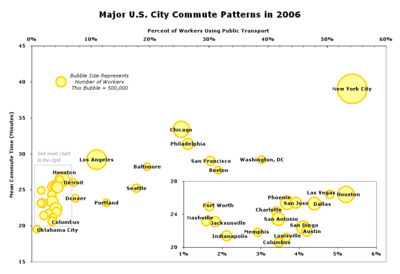

New York City is distinguished from other cities in the United States by its significant use of public transportation. New York City has, by far, the highest rate of public transportation use of any American city, with 54.2% of workers commuting to work by this means in 2006.[4] About one in every three users of mass transit in the United States and two-thirds of the nation's rail riders live in New York City or its suburbs.[5] New York is the only city in the United States where over half of all households do not own a car (Manhattan's non-ownership is even higher - around 75%; nationally, the rate is 8%).[6]

New York City also has the longest mean travel time for commuters (39 minutes) among major U.S. cities.[7]

Environmental and Social Issues

New York City's uniquely high rate of public transit use makes it one of the most energy-efficient cities in the United States. Gasoline consumption in the city today is at the rate of the national average in the 1920s.[8] New York City's high rate of transit use saved 1.8 billion gallons of oil in 2006 and $4.6 billion in gasoline costs. New York saves half of all the oil saved by transit nationwide.

The reduction in oil consumption meant 11.8 million metric tons of carbon dioxide pollution was kept out of the air.[9] The New York City metro area was ranked by the Brookings Institution as the U.S. metro area with the lowest per-capita transportation-related carbon footprint and as the fourth lowest overall per-capita carbon footprint in 2005 among the 100 largest metro areas of the United States, outranked only by Honolulu and Los Angeles and Portland.[10]

The city's transportation system, and the population density it makes possible, also have other effects. Scientists at Columbia University examined data from 13,102 adults in the city's five boroughs and identified correlations between New York's built environment and public health. New Yorkers residing in densely populated, pedestrian-friendly areas have significantly lower body mass index (BMI) levels compared to other New Yorkers. Three characteristics of the city environment -- living in areas with mixed residential and commercial uses, living near bus and subway stops and living in population-dense areas -- were found to be inversely associated with BMI levels.[11]

- See also: Environmental issues in New York City

Commuting/Modal Split

Of all people who commute to work in New York City, 32% use the subway, 25% drive alone, 14% take the bus, 8% travel by commuter rail, 8% walk to work, 6% carpool, 1% use a taxi, 0.4% ride their bicycle to work, and 0.4% travel by ferry.[12] 54% of households in New York City do not own a car, and rely on public transportation.[13] While the so-called car culture dominates in most American cities, mass transit has a defining influence on New York life. The subway is a popular location for politicians to meet voters during elections and is also a major venue for musicians. Each week, more than 100 musicians and ensembles -- ranging in genre from classical to Cajun, bluegrass, African, South American and jazz -- give over 150 performances sanctioned by New York City Transit at 25 locations throughout the subway system.[14]

|

|

||||

| Texas Transportation Institute Data | New York | Los Angeles | Chicago | |

| Surveyed metro population | 17.7 million | 12.5 million | 9.8 million | |

| Annual congestion delay per person | 23 hrs | 50 hrs | 37 hrs | |

| Annual congestion cost per person | $383 | $855 | $631 | |

| Rush hours per day | 6 hrs | 8 hrs | 8 hrs | |

| Annual passenger miles of travel on public transit | 18.5 billion | 2.8 billion | 2.2 billion | |

| Annual congestion cost saved by public transit | $4.9 billion | $2.2 billion | $1.3 billion | |

| Excess fuel consumed per person due to congestion | 11 gal (42 L) |

33 gal (125 L) |

23 gal (87 L) |

|

| Data from 2003 TTI Urban Mobility Report | ||||

3.7 million people were employed in New York City; Manhattan is the main employment center with 56% of all jobs.[15] Of those working in Manhattan, 30% commute from within Manhattan, while 17% come from Queens, 16% from Brooklyn, 8% from the Bronx, and 2.5% from Staten Island. Another 4.5% commute to Manhattan from Nassau County and 2% from Suffolk County on Long Island, while 4% commute from Westchester County. 5% commute from Bergen and Hudson counties in New Jersey.[15] Some commuters come from Fairfield County in Connecticut. Some New Yorkers reverse commute to the suburbs: 3% travel to Nassau County, 1.5% to Westchester County, 0.7% to Hudson County, 0.6% to Bergen County, 0.5% to Suffolk County, and smaller percentages to other places in the metropolitan area.[15]

Intracity Transportation

Railroads

By far the dominant mode of transportation in New York City is rail. Only 6% of shopping trips in Manhattan's Central Business District involve the use of a car.[16] The city's public transportation network is the most extensive and among the oldest in North America. Responsibility for managing the various components of the system falls to several government agencies. The largest and most important is the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), a public benefit corporation in the state of New York, which runs all of the city's subways and buses and two of its three commuter rail networks. Ridership in the city increased 36% to 2.2 billion annual riders from 1995 to 2005, far outpacing population growth.[17] Average weekday subway ridership was 5.076 million in September 2006, while combined subway and bus ridership on an average weekday that month was 7.61 million.[18]

- New York City Subway

The New York City Subway is the largest rapid transit system in the world when measured by track mileage (656 miles, or 1,056 km of mainline track), and the fourth-largest when measured by annual ridership (1.4 billion passenger trips in 2005).[5] It is the second-oldest subway system in the United States after the rapid transit system in Boston. In 2002, an average 4.8 million passengers used the subway each weekday. During one day in September 2005, 7.5 million daily riders set a record for ridership. Life in New York City is so dependent on the subway that the city is home to two of only three 24-hour subway systems in the world.[19] The city's 26 subway lines run through all boroughs except Staten Island, which is served by the Staten Island Railway.

Subway riders pay with the MetroCard, which is also valid on all other rapid transit systems and buses in the city, as well as the Roosevelt Island tramway. The MetroCard has completely replaced tokens, which were used in the past, to pay fares. Fares are loaded electronically on the card.

- PATH

The Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) is a subway system that links Manhattan, in New York State, to Jersey City, Hoboken, Harrison, and Newark, in New Jersey. The primary transit link between Manhattan and New Jersey, PATH carries 240,000 passengers each weekday on four lines.[20]

While some PATH stations are adjacent to subway stations in New York City and Newark as well as Hudson-Bergen Light Rail stations in New Jersey, there are no free transfers. The PATH system spans 13.8 miles (22.2 km) of route mileage, not including track overlap.[21] Like the New York City Subway, PATH operates 24 hours a day. Opened in 1908 as the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, a privately owned corporation, PATH since 1962 has been operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

- Airport services

Kennedy and Newark airports are served by intermodal rail systems. AirTrain JFK is an 8.1 mile (13 km) rapid transit system that connects Kennedy to New York's subway and commuter rail network in Queens. It also provides free transit between airport terminals. For trips beyond the airport the train costs $5. Roughly 4 million people rode the AirTrain to and from Kennedy in 2006, an increase of about 15% over 2005.[22] AirTrain Newark is a 1.9 mile (3 km) monorail system connecting Newark's three terminals to commuter and intercity trains running on the Northeast Corridor rail line.

- Commuter rail

New York City's commuter rail system is the most extensive in the United States, with about 250 stations and 20 rail lines serving more than 150 million commuters annually in the tri-state region.[23] Commuter rail service from the suburbs is operated by two agencies. The MTA operates the Long Island Rail Road on Long Island and the Metro-North Railroad in the Hudson Valley and Connecticut. New Jersey Transit operates the rail network on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River. These rail systems converge at the two busiest train stations in the United States, Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal, both in Manhattan.

- Intercity Rail

Intercity train service from New York City is provided by Amtrak. 54 trains run each day on the busiest route, New York to Philadelphia. For trips of less than 500 miles to other Northeastern cities Amtrak is often cheaper and faster than air travel. Amtrak accounts for 47% of all non-automobile intercity trips between New York and Washington, D.C. and about 14% of all intercity trips (including those by automobile) between those cities.[24] Amtrak's high-speed Acela trains run from New York to Boston and Washington, D.C. using tilting technology and fast electric locomotives. New York City's Penn Station is the busiest Amtrak station in the United States by annual boardings. In 2004 it saw 4.4 million passenger boardings, more than double the next busiest station, Union Station in Washington, D.C.[25]

Major destinations with frequent service include Albany, Baltimore, Boston, New Haven, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., as well as the Canadian cities Toronto and Montreal. There are also trains to Upstate New York, New England and destinations in the South and Midwest.

Buses

- See also: New York City Transit buses, MTA Bus Company, Buses in New York City, and Select Bus Service

New York City's bus network is extensive, with approximately 5,800 buses carrying about 2.01 million passengers every day on more than 200 local routes and 30 express routes.[26] Buses owned by MTA account for 80% of the city's surface mass transit.[5] New York City has the largest clean air diesel-hybrid and compressed natural gas bus fleet in the United States.[26]

Buses are labeled with a number and a prefix identifying the primary borough (B for Brooklyn, Bx for the Bronx, M for Manhattan, Q for Queens, and S for Staten Island). Express buses operated under MTA New York City Bus use the letter "x" rather than a borough label. Express buses routes operated under MTA Bus formerly controlled by the NYC Department of Transportation use a two-borough system with M at the end (i.e., BxM, QM, or BM).

The Port Authority Bus Terminal, near Times Square, is the busiest bus station in the United States and the main gateway for interstate buses into New York City. The terminal serves both commuter routes, mainly operated by New Jersey Transit, and national routes operated by companies such as Greyhound and Peter Pan.[27] Two discount services, Boltbus and Megabus announced discount intercity coach services to begin in late March 2008.

Intercity bus stations

Intercity bus operators use the following stations:

| Borough | Major terminals |

|---|---|

| Manhattan: |

|

| Brooklyn: |

|

| Queens: |

|

Ferries

The busiest ferry in the United States is the Staten Island Ferry, which annually carries over 19 million passengers on the 5.2 mile (8.4 km) run between Staten Island and Lower Manhattan. Service is provided 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and takes approximately 25 minutes each way. Each day approximately five boats transport almost 65,000 passengers during 104 boat trips. Over 33,000 trips are made annually.[30] The Ferry has remained free of charge since 1997. The charge for vehicles is $3, however, vehicles have not been allowed on the Ferry since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Bicycles are allowed on the lower level for free, as well. The ferry ride is a favorite of tourists as it provides excellent views of the Lower Manhattan skyline and the Statue of Liberty.

Major privately run ferry companies include the BillyBey Ferry Company and NY Waterway who operate several routes from New Jersey to Manhattan; SeaStreak, which provides service from Monmouth County to Manhattan; New York Water Taxi, which provides service from Brooklyn and Queens to Manhattan; and Liberty Water Taxi which provides service from Liberty State Park and Jersey City to the World Financial Center.

Private cars

Around 48% of New Yorkers own cars, yet fewer than 30% use them to commute to work, most finding public transportation cheaper and more convenient for that purpose, due in large part to traffic congestion which also slows buses. To ease traffic, the Mayor, Michael Bloomberg, in 2007 proposed congestion pricing for motor vehicles entering Manhattan's business district from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. However, this proposal was defeated when Sheldon Silver Speaker of the New York State Assembly announced that the bill would not come up for a vote in his chamber.

Traffic on highways at the edge of the area would not be charged.[31] Transit buses, emergency vehicles, taxis and for-hire vehicles, and vehicles with handicapped license plates, would also not be charged the fee. Vehicles would be charged only once per day.[31]

An advanced convergence indexing road traffic monitoring system was installed in New York City for testing purposes in May 2008.

Roads

Despite New York's reliance on public transit, roads are a defining feature of the city. Manhattan's street grid plan greatly influenced the city's physical development. Several of the city's streets and avenues, like Broadway, Wall Street and Madison Avenue are also used as shorthand or metonym in American vernacular for national industries located there: theater, finance, and advertising, respectively.

There are twelve avenues that run parallel to the Hudson River, and 220 numbered streets that run perpendicular to the river.

- See also: Geography and environment of New York City

Bridges and Tunnels

With its Gothic-revival double-arched stone towers and diagonal suspension wires, the Brooklyn Bridge is one of the city's most recognized architectural structures, depicted by artists such as Hart Crane and Georgia O'Keefe. The Brooklyn Bridge's main span is 1,596 feet and 6 inches, and was the longest in the world when it was completed. The Williamsburg Bridge and Manhattan Bridge are the two others in the trio of architecturally-notable East River crossings. The Queensboro Bridge, which links Manhattan and Queens, is an important piece of cantilever bridge design. The borough of Staten Island is connected to Brooklyn through the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The towers of the Verrazano, which rise 650 feet above the water, are 4,260 feet apart; these towers are so far away from each other, due to the length of the main span, that there is a 13⁄8 inches (34 mm) displacement between the theoretical position of the side at the top of the tower, and the actual position, due to the Earth's curvature.

New York has historically been a pioneer in tunnel construction. The Lincoln Tunnel, which carries 120,000 vehicles per day under the Hudson River between New Jersey and Manhattan, is the world's busiest vehicular tunnel. The Holland Tunnel, also under the Hudson River, was the first mechanically ventilated vehicular tunnel in the world and is considered a National Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers. Two other notable tunnels connect Manhattan to other places; one is the Queens Midtown Tunnel, and the other the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. At 9,117 feet (2,779 m), the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel is the longest underwater tunnel in North America.

Expressways

A less favored alternative to commuting by rail and boat is the New York region's outdated and congested expressway network, designed by Robert Moses. The city's extensive network of expressways includes four primary Interstate Highways: I-78, I-80, I-87 and I-95. I-278 serves as a partial beltway around the city. The Long Island Expressway begins at the Queens Midtown Tunnel and runs through the heart of Queens east into the Long Island suburbs.

Also designed by Moses are a series of limited-access parkways, which are frequently congested with traffic as well, despite the fact that they were designed from the outset to only carry cars, as opposed to commercial trucks or buses. The FDR Drive and Harlem River Drive are two such routes through Manhattan. The Henry Hudson Parkway, the Bronx River Parkway and the Hutchinson River Parkway link the Bronx to nearby Westchester County and its parkways, and the Grand Central Parkway and Belt Parkway provide similar functions for Long Island's parkway system.

Taxis

There are 13,087 taxis operating in New York City, not including over 40,000 other for-hire vehicles.[32] Their distinctive yellow paint has made them New York icons.

Taxicabs are operated by private companies and licensed by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission. "Medallion taxis", the familiar yellow cabs, are the only vehicles in the city permitted to pick up passengers in response to a street hail. A cab’s availability is indicated by the lights on the top of the car. When just the center light showing the medallion number is lit, the cab is empty and available. When no lights are lit, the cab is occupied by passengers.

Fares begin at US$2.50 (US$3.00 after 8:00pm, and US$3.50 during the peak weekday hours of 4:00pm to 8:00pm) and increase based on the distance traveled and time spent in slow traffic. The passenger also must pay the fare whenever a cab is driven through a toll. The average cab fare in 2000 was US$6.00; over US$1 billion in fares were paid that year in total.[33]

241 million passengers rode in New York taxis in 1999. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, of the 42,000 cabbies in New York, 82% are foreign born: 23% from the Caribbean (the Dominican Republic and Haiti), and 20% from South Asia (India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh).

In 2005, New York introduced incentives to replace its current yellow cabs with electric hybrid vehicles [34] then in May 2007, New York City Mayor, Michael Bloomberg, proposed a five-year plan to switch New York City's taxicabs to more fuel-efficient hybrid vehicles as part of an agenda for New York City to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as well as surging fuel costs.[35]

Pedestrians and Bicycles

Cycling in New York City is a growing mode of transport. An estimated 120,000 city residents bicycle on a typical day, and make 400,000 trips each day, equivalent to the number of the ten most popular bus routes in the city.[36] The City Department of Transportation estimates there are an additional two in-line skaters for every cyclist in New York. The city has 420 miles of bike lanes (as of 2005) including the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway and has in recent years expanded protected bike lanes on major thoroughfares and on bridges across the East River. As part of PlaNYC 2030, bike lanes will be added at a rate of about 100 miles per year until 2010, and 1,800 miles should be completed by 2030. More than 500 people annually work as bicycle rickshaw drivers, who in 2005 handled one million passengers.[37] However, the City Council recently voted to curtail and license pedicab drivers, and will only allow 325 pedicab licenses. The city also annually presents the largest recreational cycling event in the United States, the Five Boro Bike Tour, in which 30,000 cyclists ride 42 miles (65 km) through the city's boroughs.

Walk and bicycle modes of travel account for 21% of all modes for trips in the city; nationally the rate for metro regions is about 8%.[38] In 2000 New York had the largest number of walking commuters among large American cities in both total number and as a proportion of all commuters: 517,290, or 5.6%.[39] By way of comparison, the next city with the largest proportion of walking commuters, Boston, had 119,294 commuter pedestrians, amounting to 4.1% of that city's commuters.[39]

Semi-formal

New York has many forms of semi-formal public transportation, including "dollar vans" and "Chinese vans." Dollar vans serve major corridors in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx that lack adequate subway service. In 2006, the New York City Council began debate on greater industry regulation, including requiring all dollar vans to be painted in a specific color to make them easier to recognize, similar to the public light buses in Hong Kong.[40] The vans pick up and drop off anywhere along a route, and payment is made at the end of a trip.

Similar to dollar vans, Chinese vans serve predominantly Chinese and other East Asian communities in Brooklyn's Chinatown, Manhattan's Chinatown, Elmhurst and Flushing.

There are also highly competitive Chinatown bus lines operating routes from New York City's Chinatowns to other Chinatowns in the Northeast, with frequent service to major cities like Boston and Philadelphia. These bus companies use full-size coaches and offer fares much lower than traditional carriers like Greyhound. However, traditional carriers Greyhound and Coach USA have gone after these carriers by offering online fares as low as $1 on BoltBus, NeOn, and Megabus services.

There are numerous other transportation services in the city, including RightRides.org, a free car service operated by a grassroots nonprofit that shuttles women and transgender individuals home on Saturday nights from midnight to 3 a.m. in Manhattan, Queens, the Bronx and Brooklyn. RightRides is made possible by volunteer teams driving vehicles donated by Zipcar, a membership-based carsharing company providing hourly or daily car rentals in New York City to its members, who often do not own cars.

Aerial tramway

Built in 1976 to shuttle island residents to Midtown, the Roosevelt Island Tramway was originally intended to be a temporary commuter link for use until a subway station was established for the island. However, when the subway finally connected to Roosevelt Island in 1989, the tram was too popular to discontinue use.

The Tramway is operated by the Roosevelt Island Operating Corp (RIOC). Each cable car has a capacity of 125 passengers. Travel time from Roosevelt Island to Manhattan is just under five minutes and the fare is the same as a subway ride.

In 2006, service was suspended on the tramway for six months after a service malfunction that required all passengers to be evacuated.

Port Infrastructure

Airports

New York City is the top international air passenger gateway to the United States.[41] 100 million travelers used the city's airports in 2005; New York is the busiest air gateway in the nation.[42]

The city is served by three major airports: John F. Kennedy International (also known as JFK), Newark Liberty International, and LaGuardia. Teterboro serves as a primary general aviation airport. JFK and Newark both connect to regional rail systems by a light rail service.[43]

JFK and Newark serve long-haul domestic and international flights. The two airports' outbound international travel accounted for about a quarter of all U.S. travelers who went overseas in 2004.[44] LaGuardia caters to short-haul and domestic destinations.

JFK is the major entry point for international arrivals in the United States and is the largest international air freight gateway in the nation by value of shipments.[45] About 100 airlines from more than 50 countries operate direct flights to JFK. The JFK-London Heathrow route is the leading U.S. international airport pair.[46] The airport is located along Jamaica Bay near Howard Beach, Queens, about 12 miles east of downtown Manhattan.

Newark was the first major airport serving New York City and is the fifth busiest international air gateway to the United States.[41] Amelia Earhart dedicated the Newark Airport Administration Building in 1935, which was North America's first commercial airline terminal. In 2003, Newark became the terminus of the world's longest non-stop scheduled airline route, Continental's service to Hong Kong. In 2004, Singapore Airlines broke Continental's record by starting direct 18-hour flights to Singapore. The airport is located in Newark, New Jersey, about 12 miles west of downtown Manhattan.

LaGuardia, the smallest of New York's primary airports, handles domestic flights. It is named for Fiorello H. LaGuardia, the city's great Depression-era mayor known as a reformist and strong supporter of the New Deal. A perimeter rule prohibits incoming and outgoing flights that exceed 1,500 miles (2,400 km) except on Saturdays, when the ban is lifted, and to Denver, which has a grandfathered exemption. As a result, most transcontinental and international flights use JFK and Newark.[47] The airport is located in northern Queens about 6 miles from downtown Manhattan.

Manhattan has three public heliports, used mostly by business travelers. A regularly-scheduled helicopter service operates flights to JFK Airport from the Downtown Manhattan Heliport, located at the eastern end of Wall Street.

- See also: Transportation to New York City area airports

Seaports

The New York Harbor, with its natural advantages of deep water channels and protection from the Atlantic Ocean, has historically been one of the most important ports in the United States, and is now the third busiest in the United States, if New Jersey is included, behind Los Angeles and Long Beach, California in the amount of volume. Each year, more than 25 million tons of oceanborne general cargo moves through New York, including 4.5 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) of containerized cargo. In 2005 more than 5,300 ships delivered goods to the port that went to 35% of the U.S. population.[48] The port is experiencing rapid growth. Shipments increased nearly 12% in 2005. There are three cargo terminals and a passenger terminal on the New York City side of the harbor, including the Howland Hook Marine Terminal, Red Hook Container Terminal, Brooklyn Marine Terminal, and New York Cruise Terminal; three additional cargo terminals are on the New Jersey side.

The Port of New York is also a major hub for passenger ships. More than half a million people depart annually from Manhattan's cruise ship terminal on the Hudson River, accounting for five percent of the worldwide cruise industry and employing 21,000 residents in the city. The Queen Mary 2, the world's second largest passenger ship and one of the few traditional ocean liners still in service, was designed specifically to fit under the Verrazano Bridge, itself the longest suspension bridge in the United States. The Queen Mary 2 makes regular ports of call on her transatlantic runs from Southampton, England. The city is building a new cruise ship terminal in Red Hook, Brooklyn.

Originally focused on Brooklyn's waterfront, especially at the Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park, most container ship cargo operations have shifted to the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal on the other side of the bay. The terminal, operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, is the largest port complex on the East Coast. $114.54 billion of cargo passed through the Port of New York and New Jersey in 2004. The top five trading partners at the port are China, Italy, Germany, Brazil and India.

Water quality in the New York Harbor has improved dramatically since passage of the Clean Water Act and extensive harbor cleanup projects. A common misconception is that the Upper Bay is devoid of marine life. It actually supports a diverse population of marine species, including striped bass. New Yorkers regularly kayak and sail in the harbor, which has become a major recreational site for the city. Water quality problems persist in Long Island Sound, however.

Future and Proposed Projects

Several proposals for expanding the New York City transit system are in various stages of discussion, planning, or initial funding. Some of them would compete with others for available funding.

- In January 2007, the Port Authority approved plans for the $78.5 million purchase of a lease of Stewart Airport in Newburgh, New York as a 4th major airport for the area.[49]

- PATH World Trade Center station, whose construction began in late 2005, will replace the temporary PATH terminal that replaced the one destroyed in the September 11, 2001 attacks. This new central terminal, designed by Santiago Calatrava, will allow easy transfer between the PATH system, several subway lines and proposed new projects. It is expected to serve 250,000 travelers daily.

- Fulton Street Transit Center, a $750 million project in Lower Manhattan that will improve access to and connections between 12 subway lines, PATH service and the World Trade Center site. Construction began in 2005 and will be finished in 2009.

- Moynihan Station would expand Penn Station into the James Farley Post Office building across the street. As of September 2007, work has not yet begun on this project, which is still in the design phase.

- Second Avenue Subway, a new north-south line, first proposed in 1929, would run from 125th Street in Harlem to Hanover Square in lower Manhattan. The first phase, from 63rd Street to 96th Street, is in pre-construction, and is scheduled to be finished in 2013.

- IRT Flushing Line Extension would extend the 7 service (Flushing line) west along 42nd Street from its current terminus at Times Square, then south along 11th Avenue to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center. This project is approved, and in the pre-construction stage. Completion is scheduled for 2011, at the earliest.

- East Side Access project will route some Long Island Rail Road Trains to Grand Central Terminal instead of Penn Station. Since many, if not most, LIRR commuters work on the east side of Manhattan, many in walking distance of Grand Central, this project will save travel time and reduce congestion at Penn Station and on subway lines connecting it with the east side. It will also greatly expand the hourly capacity of the LIRR system. Completion is scheduled for 2013.

- The Lower Manhattan-Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project would extend an existing Long Island Rail Road line from Jamaica Station, with a new 3-mile tunnel under the East River from downtown Brooklyn to Manhattan. AirTrain JFK-compatible cars would run along the new route, connecting John F. Kennedy International Airport and Jamaica with Lower Manhattan. This project is still just a proposal, although it has the support of Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

- Trans-Hudson Express Tunnel would add a second pair of railroad tracks under the Hudson River, connecting an expanded Penn Station to NJ Transit lines. This project has been approved, and is slated to begin construction in 2009, with completion in 2016 at the earliest.

- Although New York City does not have light rail, a few proposals exist:

- There are plans to convert 42nd Street into a light rail transit mall which would be closed to all vehicles except emergency vehicles [6]. The idea was previously planned in the early 1990s, and was approved by the City Council in 1994, but stalled due to lack of funds.

- Staten Island light rail proposals have found political support from Senator Charles Schumer and local political and business leaders.

- JFK Airport is undergoing a US$10.3 billion redevelopment, one of the largest airport reconstruction projects in the world. In recent years, Terminal One, Terminal Four and Terminal Nine have been reconstructed, and work has begun on a new Terminal Five. The remaining five terminals are slated for demolition or reconstruction.

- Santiago Calatrava has also proposed an aerial gondola system linking Manhattan, Governors Island and Brooklyn as part of the city's plans to develop the island.

- As part of a long-term plan to manage New York City's environmental sustainability, Mayor Michael Bloomberg released several proposals to increase mass transit usage and improve overall transportation infrastructure.[50] Apart from support of the above capital projects, these proposals include the implementation of bus rapid transit, the reopening of closed LIRR and Metro-North stations, new ferry routes, better access for cyclists, pedestrians and intermodal transfers, and a congestion pricing zone for Manhattan south of 86th Street.

See also

- Mass transit in New York City

- Cycling in New York City

- New York City Department of Transportation

- List of U.S. cities with most pedestrian commuters

Further reading

- Taxi!: Cabs and Capitalism in New York City, Biju Mathew 2005

- New York Underground, Julia Solis 2004

- The Works: Anatomy of a City, Kate Ascher 2005

- Underground Harmonies: Music and Politics in the Subways of New York , Susie J. Tanenbaum 1995

References

- ↑ Burrows, et al. (1999). Gotham. Oxford Press. ISBN 0195116348.

- ↑ James Blaine Walker, Fifty Years of Rapid Transit, 1864-1917, published 1918, pp. 162-191

- ↑ Caro, Robert A. (1975). The Power Broker; Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Vintage Books. ISBN 0394720245.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2006, Table S0802

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Metropolitan Transportation Authority. "The MTA Network". Retrieved on 2006-05-17.

- ↑ Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation (2001). "Highlights of the 2001 National Household Travel Survey". Retrieved on 2006-05-21.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2006, Table S0802

- ↑ Jervey, Ben (2006). The Big Green Apple. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0762738359. See Metro New York article:[1]

- ↑ "A Better Way to Go: Meeting America's 21st Century Transportation Challenges with Modern Public Transit" (PDF). U.S. Public Interest Research Group (March 2008). Retrieved on 2008-04-23.

- ↑ Sarzynski, Andrea, Shrinking the Carbon Footprint of Metropolitan America (Brookings Institute: 2008)[2]

- ↑ Andrew Rundle, Dr. P.H. (2007-03). "Living Near Shops, Subways Linked to Lower BMI in New York City", American Journal of Health Promotion. See also this news release and this article.

- ↑ "Table B08406. Sex of Workers by Means of Transportation for Workplace Geography - Universe: Workers 16 Years and Over". 2004 American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Table B08201. Household Size by Vehicles Available - Universe: Households". 2004 American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ Metropolitan Transportation Authority (2007). "Music Under New York". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "County-To-County Worker Flow Files". Census 2000. United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ Transportation Alternatives (2006-02). "Necessity or Choice? Why People Drive in Manhattan". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ The New York Times (2006-08-24). "M.T.A. Ridership Grows Faster Than Population". Retrieved on 2006-08-26. See also "MTA Ridership takes Express with 31% Surge." August 24, 2006 The New York Post.[3]

- ↑ The New York Times (2006-11-29). "Manhattan: Record Use for Subways". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ The New York City Subway and the PATH both operate 24 hours a day.

- ↑ American Public Transportation Association. "APTA Ridership Report: Third Quarter 2006". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Hoboken Terminal (1995-05). "PATH at a Glance". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ The New York Times (2007-01-17). "Manhattan: Train-to-Plane Use Sets Record". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Metropolitan Transportation Authority. "About the MTA Long Island Railroad". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Congressional Budget Office (2003-09). "The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ "TABLE 1-8 Top 50 Amtrak Stations by Number of Boardings: Fiscal Year 2004]". Transportation Statistics Annual Report 2005. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation (2005-11). Retrieved on 2006-06-11.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Metropolitan Transportation Authority (2006-05-01). "2005 Annual Report". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. "History of the Port Authority Bus Terminal". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ "[4]," Greyhound Lines

- ↑ "Queens Vil, New York," Greyhound Lines

- ↑ New York City Department of Transportation. "Facts about the Ferry". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Mobility Needs Assessment: 2007-2030, p. 143-144

- ↑ New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (2006-03-09). "The State of the NYC Taxi". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission. "Passenger Information: Rate of Fare". Retrieved on 2006-06-11.

- ↑ New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (2005-09-08). "Taxi and Limousine Commission Votes Today to Authorize Cleaner, Greener Hybrid-Electric Taxicabs". Retrieved on 2006-08-16.

- ↑ Rivera, Ray (2007, May 23) Mayor Plans an All-Hybrid Taxi Fleet. New York Times, p. B1.

- ↑ Gotham Gazette (2006-07). "Biking It". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Gotham Gazette (2006-03-06). "Regulating Rickshaws". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Transportation (2004-12). "2001 National Household Travel Survey: Summary of Travel Trends". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation (2006-01-05). "Journey to Work Trends in the United States and its Major Metropolitan Areas, 1960-2000". Retrieved on 2007-02-18. Note that the U.S. Census reports different figures. See [5]

- ↑ The New York Times (2006-04-30). "New Yorkers May Soon Be Able to Tell A Van, as They Do a Cab, by Its Color". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Table 10: Top 20 U.S. Gateways for Nonstop International Air Travel: 1990, 1995, and 2000". U.S. International Travel and Transportation Trends, BTS02-03. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation (2002). Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (2006-11-02). "2005 Annual Airport Traffic Report". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ See AirTrain JFK and AirTrain Newark.

- ↑ The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (2005-08-29). "Port Authority Leads Nation in Record-Setting Year for Travel Abroad". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation (2004). "America's Freight Transportation Gateways". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation (2002). "U.S. International Travel and Transportation Trends, BTS02-03". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ The New York Sun (2005-08-05). "Long Distance at La Guardia". Retrieved on 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Gotham Gazette (2006-03). "New York's Port, Beyond Dubai". Retrieved on 2007-02-19.

- ↑ The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (2007-01-25). "Port Authority Authorizes Purchase of Operating Lease at Stewart International Airport". Retrieved on 2007-02-19.

- ↑ PlaNYC 2030: Transportation initiatives

External links

- Regional Plan Association

- New York Metropolitan Transportation Council, an association of urban and suburban agencies

|

|||||||||||