Toxoplasmosis

| Toxoplasmosis Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

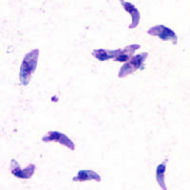

| T. gondii tachyzoites | |

| ICD-10 | B58. |

| ICD-9 | 130 |

| DiseasesDB | 13208 |

| MedlinePlus | 000637 |

| eMedicine | med/2294 |

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii.[1] The parasite infects most genera of warm-blooded animals, including humans, but the primary host is the felid (cat) family. Animals are infected by eating infected meat, by ingestion of faeces of a cat that has itself recently been infected, or by transmission from mother to fetus. Cats have been shown as a major reservoir of this infection.[2]

Up to one third of the world's population is estimated to carry a Toxoplasma infection.[3] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that overall seroprevalence in the United States as determined with specimens collected by the National Health and Nutritional Assessment Survey (NHANES) between 1999 and 2004 was found to be 10.8%, with seroprevalence among women of childbearing age (15 to 44 years) of 11%.[4]

During the first few weeks, the infection typically causes a mild flu-like illness or no illness. After the first few weeks of infection have passed, the parasite rarely causes any symptoms in otherwise healthy adults. However, people with a weakened immune system, such as those infected with HIV or pregnant, may become seriously ill, and it can occasionally be fatal. The parasite can cause encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and neurologic diseases and can affect the heart, liver, and eyes (chorioretinitis).

Contents |

Symptoms

Infection has two stages:

Acute toxoplasmosis

During acute toxoplasmosis, symptoms are often influenza-like: swollen lymph nodes, or muscle aches and pains that last for a month or more. Rarely, a patient with a fully functioning immune system may develop eye damage from toxoplasmosis. Young children and immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS, those taking certain types of chemotherapy, or those who have recently received an organ transplant, may develop severe toxoplasmosis. This can cause damage to the brain or the eyes. Only a small percentage of infected newborn babies have serious eye or brain damage at birth.

Latent toxoplasmosis

Most patients who become infected with Toxoplasma gondii and develop toxoplasmosis do not know it. In most immunocompetent patients, the infection enters a latent phase, during which only bradyzoites are present, forming cysts in nervous and muscle tissue. Most infants who are infected while in the womb have no symptoms at birth but may develop symptoms later in life.[5]

Diagnosis

Detection of Toxoplasma gondii in human blood samples may be achieved by using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[6] Inactive cysts may exist in a host which would evade detection.

Transmission

Transmission may occur through:

- Ingestion of raw or partly cooked meat, especially pork, lamb, or venison containing Toxoplasma cysts. Infection prevalence in countries where undercooked meat is traditionally eaten has been related to this transmission method. Oocysts may also be ingested during hand-to-mouth contact after handling undercooked meat, or from using knives, utensils, or cutting boards contaminated by raw meat.[7]

- Ingestion of contaminated cat faeces. This can occur through hand-to-mouth contact following gardening, cleaning a cat's litter box, contact with children's sandpits, or touching anything that has come into contact with cat faeces.

- Drinking water contaminated with Toxoplasma.

- Transplacental infection in utero.

- Receiving an infected organ transplant or blood transfusion, although this is extremely rare.[7]

The cyst form of the parasite is extremely hardy, capable of surviving exposure to freezing down to −12 degrees Celsius (10 degrees Fahrenheit), moderate temperatures and chemical disinfectants such as bleach, and can survive in the environment for over a year. It is, however, susceptible to high temperatures—above 66 degrees Celsius (150 degrees Fahrenheit), and is thus killed by thorough cooking, and would be killed by 24 hours in a typical domestic freezer.[8]

Cats excrete the pathogen in their faeces for a number of weeks after contracting the disease, generally by eating an infected rodent. Even then, cat faeces are not generally contagious for the first day or two after excretion, after which the cyst 'ripens' and becomes potentially pathogenic. Studies have shown that only about 2% of cats are shedding oocysts at any one time, and that oocyst shedding does not recur even after repeated exposure to the parasite. Although the pathogen has been detected on the fur of cats, it has not been found in an infectious form, and direct infection from handling cats is generally believed to be very rare.

Pregnancy precautions

Congenital toxoplasmosis is a special form in which an unborn child is infected via the placenta. A positive antibody titer indicates previous exposure and immunity and largely ensures the unborn baby's safety. A simple blood draw at the first pre-natal doctor visit can determine whether or not the woman has had previous exposure and therefore whether or not she is at risk. If a woman receives her first exposure to toxoplasmosis while pregnant, the baby is at particular risk. A woman with no previous exposure should avoid handling raw meat, exposure to cat feces, and gardening (cat feces are common in garden soil). Most cats are not actively shedding oocysts and so are not a danger, but the risk may be reduced further by having the litterbox emptied daily (oocysts require longer than a single day to become infective), and by having someone else empty the litterbox. However, while risks can be minimized, they cannot be eliminated. For pregnant women with negative antibody titer, indicating no previous exposure to T. gondii, as frequent as monthly serology testing is advisable as treatment during pregnancy for those women exposed to T. gondii for the first time decreases dramatically the risk of passing the parasite to the fetus.

Despite these risks, pregnant women are not routinely screened for toxoplasmosis in most countries (France[9], Austria[9] and Italy[10] being the exceptions) for reasons of cost-effectiveness and the high number of false positives generated as the disease is so rare (an example of Bayesian statistics). As invasive prenatal testing incurs some risk to the fetus (18.5 pregnancy losses per toxoplasmosis case prevented[9]), postnatal or neonatal screening is preferred. The exceptions are cases where foetal abnormalities are noted, and thus screening can be targeted.[9]

Some regional screening programmes operate in Germany, Switzerland and Belgium.[10]

Treatment is very important for recently infected pregnant women, to prevent infection of the fetus. Since a baby's immune system does not develop fully for the first year of life, and the resilient cysts that form throughout the body are very difficult to eradicate with anti-protozoans, an infection can be very serious in the young.

Transplacental transmission:(a) infection in 1st trimester - incidence of transplacental infection is low (15%) but disease in neonate is most severe. (b) infection in 3rd trimester - incidence of transplacental infection is high (65%) but infant is usually asymptomatic at birth.

Treatment

Treatment is often only recommended for people with serious health problems, because the disease is most serious when one's immune system is weak.

Medications that are prescribed for acute Toxoplasmosis are:

- Pyrimethamine — an antimalarial medication.

- Sulfadiazine — an antibiotic used in combination with pyrimethamine to treat toxoplasmosis.

- clindamycin — an antibiotic. This is used most often for people with HIV/AIDS.

- spiramycin — another antibiotic. This is used most often for pregnant women to prevent the infection of their child.

(Other antibiotics such as minocycline have seen some use as a salvage therapy).

In people with latent toxoplasmosis, the cysts are immune to these treatments, as the antibiotics do not reach the bradyzoites in sufficient concentration.

Medications that are prescribed for latent Toxoplasmosis are:

- atovaquone — an antibiotic that has been used to kill Toxoplasma cysts inside AIDS patients. [11]

- clindamycin — an antibiotic which, in combination with atovaquone, seemed to optimally kill cysts in mice.[12]

However, in latent infections successful treatment is not guaranteed, and some subspecies exhibit resistance.

Biological modifications of the host

The parasite itself can cause various effects on the host body, some of which are not fully understood.

Reproductive changes

A recent study has indicated Toxoplasmosis correlates strongly with an increase in boy births in humans.[13] According to the researchers, "depending on the antibody concentration, the probability of the birth of a boy can increase up to a value of 0.72 ... which means that for every 260 boys born, 100 girls are born." The study also notes a mean rate of 0.608 (as opposed to the normal 0.51) for Toxoplasma-positive mothers. The study explains that this effect may not significantly influence the actual sex ratio of children born in countries with high rates of latent toxoplasmosis infection because "In high-prevalence countries, most women of reproductive age have already been infected for a long time and therefore have only low titres of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies. Our results suggest that low-titres women have similar sex ratios to Toxoplasma-negative women."[13]

Behavioral changes

It has been found that the parasite has the ability to change the behavior of its host: infected rats and mice are less fearful of cats — in fact, some of the infected rats seek out cat-urine-marked areas. This effect is advantageous to the parasite, which will be able to sexually reproduce if its host is eaten by a cat.[14] The mechanism for this change is not completely understood, but there is evidence that toxoplasmosis infection raises dopamine levels and concentrates in the amygdala in infected mice.

The findings of behavioral alteration in rats and mice have led some scientists to speculate that toxoplasma may have similar effects in humans, even in the latent phase that had previously been considered asymptomatic. Toxoplasma is one of a number of parasites that may alter their host's behaviour as a part of their life cycle.[15] The behaviors observed, if caused by the parasite, are likely due to infection and low-grade encephalitis, which is marked by the presence of cysts in the brain, which may produce or induce production of a neurotransmitter, possibly dopamine,[16] therefore acting similarly to dopamine reuptake inhibitor type antidepressants and stimulants.

Correlations have been found between latent Toxoplasma infections and various characteristics:[17]

- Decreased novelty-seeking behaviour[18]

- Slower reactions

- Lower rule-consciousness and jealousy (in men)[18]

- More warmth and conscientiousness (in women)[18]

The evidence for behavioral effects on humans is relatively weak. No prospective research has been done on the topic, e.g., testing people before and after infection to ensure that the proposed behavior arises only afterwards. Although some researchers have found potentially important associations with toxoplasma, the causal relationship, if any, is unknown, i.e., it is possible that these associations merely reflect factors that predispose certain types of people to infection.

Studies have found that toxoplasmosis is associated with an increased car accident rate, roughly doubling or tripling the chance of an accident relative to uninfected people.[16][19] This may be due to the slowed reaction times that are associated with infection.[19] "If our data are true then about a million people a year die just because they are infected with toxoplasma," the researcher Jaroslav Flegr told The Guardian.[20] The data shows that the risk decreases with time after infection, but is not due to age.[16] Ruth Gilbert, medical coordinator of the European Multicentre Study on Congenital Toxoplasmosis, told BBC News Online these findings could be due to chance, or due to social and cultural factors associated with toxoplasma infection.[21]However there is also evidence of a delayed effect which increases reaction times.[22]

Other studies suggest that the parasite may influence personality. There are claims of toxoplasma causing antisocial attitudes in men and promiscuity[23] (or even "signs of higher intelligence"[24] ) in women, and greater susceptibility to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in all infected persons.[23] A 2004 study found that toxoplasma "probably induce[s] a decrease of novelty seeking." [25]

According to Sydney University of Technology infectious disease researcher Nicky Boulter in an article that appeared in the January/February 2007 edition of Australasian Science magazine, Toxoplasma infections lead to changes depending on the sex of the infected person. [26]

The study suggests that male carriers have lower IQs, a tendency to achieve a lower level of education and have shorter attention spans, a greater likelihood of breaking rules and taking risks, and are more independent, anti-social, suspicious, jealous and morose. It also suggests that these men are deemed less attractive to women. Women carriers are suggested to be more outgoing, friendly, more promiscuous, and are considered more attractive to men compared with non-infected controls. The results are shown to be true when tested on mice, though it is still inconclusive. A few scientists have suggested that, if these effects are genuine, prevalence of toxoplasmosis could be a major determinant of cultural differences.[27][17]

Toxoplasma's role in schizophrenia

The possibility that toxoplasmosis is one cause of schizophrenia has been studied by scientists since at least 1953. [28] These studies had attracted little attention from U.S. researchers until they were publicized through the work of prominent psychiatrist and advocate E. Fuller Torrey. In 2003, Torrey published a review of this literature, reporting that almost all the studies had found that schizophrenics have elevated rates of toxoplasma infection.[28] A 2006 paper has even suggested that prevalence of toxoplasmosis has large-scale effects on national culture. [29] These types of studies are suggestive but cannot confirm a causal relationship (because of the possibility, for example, that schizophrenia increases the likelihood of toxoplasma infection rather than the other way around).[28]

- Acute Toxoplasma infection sometimes leads to psychotic symptoms not unlike schizophrenia.

- Some anti-psychotic medications that are used to treat schizophrenia, such as Haloperidol, also stop the growth of Toxoplasma in cell cultures.

- Several studies have found significantly higher levels of Toxoplasma antibodies in schizophrenia patients compared to the general population.[30]

- Toxoplasma infection causes damage to astrocytes in the brain, and such damage is also seen in schizophrenia .

Epidemiology

In humans

The U.S. NHANES (1999-2004) national probability sample found that 10.8% of U.S. persons 6-49 years of age, and 11.0% of women 15-44 years of age, had Toxoplasma-specific IgG antibodies, indicating that they had been infected with the organism. [4] This prevalence has significantly decreased from the NHANES III (1988-1994). [31] [32]

It is estimated that between 30% and 65% of all people worldwide are infected with Toxoplasmosis. However, there is large variation countries: in France, for example, around 88% of the population are carriers, probably due to a high consumption of raw and lightly cooked meat. [33] Germany, the Netherlands and Brazil also have high prevalences of around 80%, over 80%[34] and 67% respectively. In Britain, about 22% are carriers, and South Korea's rate is only 4.3%.[17]

Two risk factors for contracting toxoplasmosis are:

- Infants born to mothers who became infected with Toxoplasma for the first time during or just before pregnancy.

- Persons with severely weakened immune systems, such as those with AIDS. Illness may result from an acute Toxoplasma infection or reactivation of an infection that occurred earlier in life.

In other animals

A University of California, Davis study of dead sea otters collected from 1998 to 2004 found that toxoplasmosis was the cause of death for 13% of the animals.[35] Proximity to freshwater outflows into the ocean were a major risk factor. Ingestion of oocysts from cat faeces is considered to be the most likely ultimate source.[36] According to an article in the New Scientist, the parasites have also been found in dolphins and whales. Researchers Black and Massie believe that anchovies, which travel from estuaries into the open ocean, may be helping to spread the disease. Michael Grigg of the US National Institute of Health mentioned that a new type of T. gondii, type X, has been found which is responsible for the large deaths of sea otters, and may be "poised to sweep the world".[37]

History

The protozoan was first discovered by Nicolle & Manceaux, who in 1908 isolated it from the African rodent Ctenodactylus gundi, then in 1909 differentiated the disease from Leishmania and named it Toxoplasmosis gondii [9][5]. The first recorded congenital case was not until 1923, and the first adult case not until 1940[9]. In 1948, a serological dye test was created by Sabin & Feldman, which is now the standard basis for diagnostic tests.[38]

Notable people with toxoplasmosis

- Arthur Ashe developed neurological problems from toxoplasmosis (and was later found to be HIV-positive)[39]

- Leslie Ash contracted toxoplasmosis in the second month of pregnancy[40]

- François, comte de Clermont, Dauphin of France and Orléans pretender to the French throne. Both he and his younger sister, Princess Blanche, are mentally disabled due to congenital toxoplasmosis.

- Sebastian Coe (British middle distance runner)

- Martina Navrátilová (tennis player) retired from a competition in 1982 with symptoms of a mystery 'virus' that were later found to be due to toxoplasmosis[41]

- Louis Wain was a prominent cat artist who later developed schizophrenia, which some believe was due to toxoplasmosis resulting from his prolonged exposure to cats.[42]

References

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. pp. 723–7. ISBN 0838585299.

- ↑ Torda A (2001). "Toxoplasmosis. Are cats really the source?". Aust Fam Physician 30 (8): 743–7. PMID 11681144.

- ↑ Montoya J, Liesenfeld O (2004). "Toxoplasmosis". Lancet 363 (9425): 1965–76. doi:. PMID 15194258.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Sanders-Lewis K, Wilson M (2007). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States, 1999-2004, decline from the prior decade". Am J Trop Med Hyg 77 (3): 405–10. PMID 17827351.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Toxoplasmosis". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (2004-11-22).

- ↑ North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Sukthana Y (2006). "Toxoplasmosis: beyond animals to humans". TRENDS in Parisitology 22 (3): 137. doi:.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 [http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01883.x De Paschale et al. (2008) Seroprevalence and incidence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the Legnano area of Italy Clinical Microbiology and Infection 14 (2), 186–189]

- ↑ "Toxoplasmosis - treatment key research". NAM & aidsmap (2005-11-02).

- ↑ Djurković-Djaković O, Milenković V, Nikolić A, Bobić B, Grujić J (2002). "Efficacy of atovaquone combined with clindamycin against murine infection with a cystogenic (Me49) strain of Toxoplasma gondii" (PDF). J Antimicrob Chemother 50 (6): 981–7. doi:. PMID 12461021. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/50/6/981.pdf.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jaroslav Flegr. Women infected with parasite Toxoplasma have more sons, Naturwissenschaften, August 2006. full text

- ↑ Berdoy M, Webster J, Macdonald D (2000). Fatal Attraction in Rats Infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B267:1591-1594. PMID 11007336

- ↑ "'Cat Box Disease' May Change Human Personality And Lower IQ", The Daily Telegraph (April 8, 2000).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Flegr J, Havlíček J, Kodym P, Malý M, Šmahel Z (2002). "Increased risk of traffic accidents in subjects with latent toxoplasmosis: a retrospective case-control study". BMC Infect Dis 2: 11. doi:. PMID 12095427.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Carl Zimmer, The Loom. A Nation of Neurotics? Blame the Puppet Masters?, 1 Aug. 2006

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Jaroslav Flegr (January 2007). "Effects of Toxoplasma on Human Behaviour". Schizophrenia Bulletin 33 (3): 757–760. doi:. PMID 17218612.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Yereli K, Balcioglu IC, Ozbilgin A. (Dec 2 2005). "Is Toxoplasma gondii a potential risk for traffic accidents in Turkey?". Forensic Sci Int. PMID 16332418.

- ↑ "Can a parasite carried by cats change your personality?", The Guardian (September 25, 2003).

- ↑ "Dirt infection link to car crashes", BBC News (August 10, 2002).

- ↑ J. Havlícek, Z. Gašová, A. P. Smith, K. Zvára and J. Flegr, Decrease of psychomotor performance in subjects with latent ‘asymptomatic’ toxoplasmosis, Parasitology (2001), 122: 515-520

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Dangerrrr: cats could alter your personality", Times Online (June 23, 2005).

- ↑ "Can a parasite carried by cats change your personality?", The Guardian (September 25, 2003).

- ↑ Novotná M, Hanusova J, Klose J, Preiss M, Havlicek J, Roubalová K, Flegr J (Jul 6 2004). "Probable neuroimmunological link between Toxoplasma and cytomegalovirus infections and personality changes in the human host". BMC Infect Dis 5: 54. doi:. PMID 16000166.

- ↑ AAP, SMH Parasite makes men dumb, women sexy, 26 Dec. 2006

- ↑ Kevin Lafferty [3]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Torrey EF, Yolken RH (2003). "Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia". Emerging Infect. Dis. 9 (11): 1375–80. PMID 14725265.free full text

- ↑ Lafferty, Kevin D. (2006). "Can the common brain parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, influence human culture?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273 (FirstCite Early Online Publishing): 2749. doi:. ISSN 0962-8452 (Paper) 1471-2954 (Online). http://www.journals.royalsoc.ac.uk/(dm021s45towy3pzbec3vjfez)/app/home/contribution.asp?referrer=parent&backto=issue,9,15;journal,8,316;linkingpublicationresults,1:102024,1.

- ↑ Wang H, Wang G, Li Q, Shu C, Jiang M, Guo Y (2006). "Prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in first-episode schizophrenia and comparison between Toxoplasma-seropositive and Toxoplasma-seronegative schizophrenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 114 (1): 40–8. doi:. PMID 16774660.

- ↑ Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Wilson M, McQuillan G, Navin T, McAuley JB (2001). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States: seroprevalence and risk factors". Am J Epidemiol 154 (4): 357–65. doi:. PMID 11495859.

- ↑ Jones J, Kruszon-Moran D, Wilson M (2003). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States, 1999-2000". Emerg Infect Dis 9 (11): 1371–4. PMID 14718078. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol9no11/03-0098.htm.

- ↑ David Adam, Guardian Unlimited. Can a parasite carried by cats change your personality?, 25 Sep. 2003

- ↑ Toxoplasmosis in the Netherlands by the Laboratory for Diagnoses for Infectious Diseases and Screening; RIVM Bilthoven [4]

- ↑ Conrad P, Miller M, Kreuder C, James E, Mazet J, Dabritz H, Jessup D, Gulland F, Grigg M (2005). "Transmission of Toxoplasma: clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment". Int J Parasitol 35 (11-12): 1155–68. doi:. PMID 16157341.

- ↑ "17:30-22:00 Treating Disease in the Developing World.". Talk of the Nation Science Friday. National Public Radio (December 16, 2005).

- ↑ Brahic, Catherine. (2008). The world's most successful bug hits dolphins.

- ↑ Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory: Laboratory Tests For The Diagnosis Of Toxoplasmosis

- ↑ Arthur Ashe, Tennis Star, is Dead at 49

- ↑ BBC News | HEALTH | Pregnancy superfoods revealed

- ↑ Parasite of the month

- ↑ "Topic 33. Coccidia and Cryptosporidium spp.". Biology 625: Animal Parasitology. Kent State Parasitology Lab (October 24, 2005). Retrieved on 2006-10-14. Includes a list of famous victims.

External links

- Parts of this article are taken from the public domain CDC factsheet: Toxoplasmosis

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||