Bactria

Bactria (Bactriana, Bākhtar in Farsi, also: بـلـخ (spelled: Bhalakh) in Arabic and Indian languages, and Daxia in Chinese) is a historical region of Greater India. Known by the ancient Greeks as "Bactriana" the region is located between the range of the Hindu Kush and the Amu Darya (Oxus); in later times, the region became known as Tokharistan. The name of the region has survived to present time in the name of Afghan province "Balkh".

Bactria was bounded on the east by the ancient region of Gandhara. The Bactrian language is an Iranian language of the Indo-Iranian sub-family of the Indo-European family.

The Bactrians are among the ancestors of the modern-day Tajiks.[1]

Contents |

Geography

Bactria is basically what is now northern Afghanistan and south-western Uzbekistan. It is a mountainous region with a moderate climate. Water is abundant and the land is very fertile. Bactria was the home of one of the Iranian tribes. Modern authors have often used the name in a wider sense, as the designation of all the countries of Central Asia.

History

Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC, also known as the "Oxus civilization") is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age culture of Central Asia, dated to ca. 2200–1700 BCE, located in present day Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centered on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus), in area covering ancient Bactria. Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Bactria was the Greek name for the area of Bactra (modern Balkh), in what is now northern Afghanistan, and Margiana was the Greek name for the Persian satrapy of Margu, the capital of which was Merv, in today's Turkmenistan.

According to some writers, Bactria was the homeland of Indo-European tribes who moved south-west into Iran and into North-Western India around 2500–2000 BCE. Later, it became the north province of the Persian Empire in Central Asia.(Cotterell, 59) It was in these regions, where the fertile soil of the mountainous country is surrounded by the Turanian desert, that the prophet Zarathushtra (Zoroaster) was said to have been born and gained his first adherents. Avestan, the language of the oldest portions of the Zoroastrian Avesta, was one of the Old Iranian languages, and is the oldest attested member of the Eastern Iranian branch of the Iranian language family.

Cyrus and Alexander

- See main article: Bactria (satrapy)

It is not known whether Bactria formed part of the Median Empire, but it was subjugated by Cyrus the Great, and from then formed one of the satrapies of the Persian empire. After Darius III of Persia had been defeated by Alexander the Great and killed in the ensuing chaos, his murderer Bessus, the satrap of Bactria, tried to organize a national resistance based on his satrapy.

Alexander conquered Sogdiana and Iran without much difficulty; it was only in to the south, beyond the Oxus, that he met strong resistance. After two years of bloody war Bactria became a province of the Macedonian empire, but Alexander never successfully subdued the people. After Alexander's death, the Macedonian empire was eventually divided up between generals in Alexander's army. Bactria became a part of the Seleucid Empire, named after its founder, Seleucus I.

Seleucid Empire

The Macedonians (and especially Seleucus I and his son Antiochus I) established the Seleucid Empire, and founded a great many Greek towns in eastern Iran, and the Greek language became dominant for some time there.

The paradox that Greek presence was more prominent in Bactria than in areas far more adjacent to Greece could possibly be explained by the supposed policy of Persian kings to deport unreliable Greeks to this the most remote province of their huge empire.

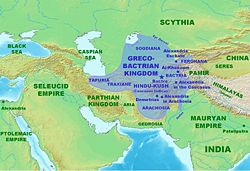

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

Main article: Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The many difficulties against which the Seleucid kings had to fight and the attacks of Ptolemy II of Egypt, gave Diodotus, satrap of Bactria, the opportunity to declare independence (about 255 BCE) and conquer Sogdiana. He was the founder of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Diodotus and his successors were able to maintain themselves against the attacks of the Seleucids—particularly from Antiochus III the Great, who was ultimately defeated by the Romans (190 BCE).

The Greco-Bactrians were so powerful that they were able to expand their territory as far as India:

- "As for Bactria, a part of it lies alongside Aria towards the north, though most of it lies above Aria and to the east of it. And much of it produces everything except oil. The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Bactria and beyond, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander...." [2]

Indo-Greek Kingdom

Main article: Indo-Greek Kingdom

The Bactrian king Euthydemus and his son Demetrius crossed the Hindu Kush and began the conquest of Northern Afghanistan and the Indus valley. For a short time, they wielded great power: a great Greek empire seemed to have arisen far in the East. But this empire was torn by internal dissensions and continual usurpations. When Demetrius advanced far into India one of his generals, Eucratides, made himself king of Bactria, and soon in every province there arose new usurpers, who proclaimed themselves kings and fought one against the other.

Most of them we know only by their coins, a great many of which are found in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. By these wars, the dominant position of the Greeks was undermined even more quickly than would otherwise have been the case. After Demetrius and Eucratides, the kings abandoned the Attic standard of coinage and introduced a native standard, no doubt to gain support from outside the Greek minority. In India, this went even further. Indo-Greek King Menander I (known as Milinda in India), recognized as a great conqueror, converted to Buddhism. His successors managed to cling to power somewhat longer, but around 10 CE all of the Greek kings were gone.

Sakas and Yuezhis

The weakness of the Greco-Bactrian empire was shown by its sudden and complete overthrow, first by the Sakas, and then by the Yuezhi (who later became known as Kushans), who had conquered Daxia (= Bactria) by the time of the visit of the Chinese envoy Zhang Qian, who was sent by the Han emperor to investigate lands to the west of China circa 126 BCE.[3]

But then its emergence, isolated thousands of miles from Greece, could only be described as a paradox. However, its cultural influences were not completely undone; an artistic style mixing western and eastern elements known as the Gandhara culture survived the empire for hundreds of years.

Contacts with China

The name Daxia appears in Chinese from the 3rd century BCE to designate a mythical kingdom to the West, possibly a consequence of the first contacts with the expansion of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and then is used by the explorer Zhang Qian in 126 BCE to designate Bactria.

The reports of Zhang Qian were put in writing in the Shiji ("Records of the Grand Historian") by Sima Qian in the 1st century BCE. They describe an important urban civilization of about one million people, living in walled cities under small city kings or magistrates. Daxia was an affluent country with rich markets, trading in an incredible variety of objects, coming as far as Southern China. By the time Zhang Qian visited Daxia, there was no longer a major king, and the Bactrian were suzerains to the nomadic Yuezhi, who were settled to the north of their territory beyond the Oxus (Amu Darya). Overall Zhang Qian depicted a rather sophisticated but demoralized people who were afraid of war.

Following these reports, the Chinese emperor Wu Di was informed of the level of sophistication of the urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia, and became interested in developing commercial relationship with them:

- "The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Ferghana (Dayuan) and the possessions of Bactria (Daxia) and Parthia (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China" (Hanshu, Former Han History).

These contacts immediately led to the dispatch of multiple embassies from the Chinese, which helped to develop the Silk Road.

Tokharistan

Following the settlement of the Yuezhi (described in the West as "Tocharians"), the general area of Bactria came to be called Tokharistan. The territory of Tokharistan was identical with Kushan Bactria, including the areas of Surkhandarya, Southern Tajikistan and Northern Afghanistan.

The first literary mentions of Tokharistan appear at the end of the 4th century in Chinese Buddhist sources (the Vibhasa-sastra). However, the first mention of the Tocharians appear much sooner, in the 1st century BCE, when Strabo mentions that "the Tokharians, together with the Assianis, Passianis and Sakaraulis, took part in the destruction of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom" in the second half of the 2nd century BCE. Ptolemy also mentions a large Tokharian tribe in Bactria, describing the central role of the Tokharians among other tribes in Bactria.

From the 1st century CE to the 3rd century CE, Tokharistan was under the rule of the Kushans. They were followed by Sassanides (Indo-Sassanids). Later, in the 5th century, it was controlled by the Xionites and the Hephthalites. In the 7th century, after a brief rule under the Turkish Khaganats, it was conquered by the Arabs and then the Mongols and much later , by Russians.

See also

- Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex

- Bactrian Gold

- Bactrian Camel

- The Bahlikas

Notes and references

- ↑ Library of Congress, "Tajikistan - Historical & Ethnic Background", (LINK): "Contemporary Tajiks are the descendants of ancient Eastern Iranian inhabitants of Central Asia, in particular the Soghdians and the Bactrians, and possibly other groups, with an admixture of Western Iranian Persians and non-Iranian peoples."

- ↑ Strabo,11.11.1

- ↑ Silk Road, North China, C. Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Beal, Samuel (trans.). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. Two volumes. London. 1884. Reprint: Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, 1969.

- Beal, Samuel (trans.). The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. London, 1911. Reprint: New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1973.

- Cotterell, Arthur. From Aristotle to Zoroaster, 1998; pages 57–59. ISBN 0-684-85596-8.

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." Second Draft Edition.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Holt, Frank Lee. Thundering Zeus: The Making of Hellenistic Bactria. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999 (hardcover, ISBN 0520211405).

- Watson, Burton (trans.). "Chapter 123: The Account of Dayuan." Translated from the Shiji by Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian of China II (Revised Edition). Columbia University Press, 1993, pages 231–252. ISBN 0-231-08164-2 (hardback), ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (paperback).

- Watters, Thomas. On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India (A.D. 629–645). Reprint: New Delhi: Mushiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1973.

External links

- Bactrian Gold

- Livius.org: Bactria

- Batriane du nord—about the Termez region, an archeological site