Tidal power

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

|

| Biofuels Biomass Geothermal Hydro power Solar power Tidal power Wave power Wind power |

Tidal power, sometimes called tidal energy, is a form of hydropower that converts the energy of tides into electricity or other useful forms of power.

Although not yet widely used, tidal power has potential for future electricity generation. Tides are more predictable than wind energy and solar power. Historically, tide mills have been used, both in Europe and on the Atlantic coast of the USA. The earliest occurrences date from the Middle Ages, or even from Roman times.[1][2]

Contents |

Generation of tidal energy

Tidal power is the only form of energy which derives directly from the relative motions of the Earth–Moon system, and to a lesser extent from the Earth–Sun system. The tidal forces produced by the Moon and Sun, in combination with Earth's rotation, are responsible for the generation of the tides. Other sources of energy originate directly or indirectly from the Sun, including fossil fuels, conventional hydroelectric, wind, biofuels, wave power and solar. Nuclear is derived using radioactive material from the Earth, geothermal power uses the heat of magma below the Earth's crust, which comes from radioactive decay.

Tidal energy is generated by the relative motion of the Earth, Sun and the Moon, which interact via gravitational forces. Periodic changes of water levels, and associated tidal currents, are due to the gravitational attraction by the Sun and Moon. The magnitude of the tide at a location is the result of the changing positions of the Moon and Sun relative to the Earth, the effects of Earth rotation, and the local shape of the sea floor and coastlines.

Because the Earth's tides are caused by the tidal forces due to gravitational interaction with the Moon and Sun, and the Earth's rotation, tidal power is practically inexhaustible and classified as a renewable energy source.

A tidal energy generator uses this phenomenon to generate energy. The stronger the tide, either in water level height or tidal current velocities, the greater the potential for tidal energy generation.

Tidal movement causes a continual loss of mechanical energy in the Earth–Moon system due to pumping of water through the natural restrictions around coastlines, and due to viscous dissipation at the seabed and in turbulence. This loss of energy has caused the rotation of the Earth to slow in the 4.5 billion years since formation. During the last 620 million years the period of rotation has increased from 21.9 hours to the 24 hours[3] we see now; in this period the Earth has lost 17% of its rotational energy. Tidal power may take additional energy from the system, increasing the rate of slowing over the next millions of years.

Categories of tidal power

Tidal power can be classified into two main types:

- Tidal stream systems make use of the kinetic energy of moving water to power turbines, in a similar way to windmills that use moving air. This method is gaining in popularity because of the lower cost and lower ecological impact compared to barrages.

- Barrages make use of the potential energy in the difference in height (or head) between high and low tides. Barrages suffer from very high civil infrastructure costs, a worldwide shortage of viable sites, and environmental issues.

Modern advances in turbine technology may eventually see large amounts of power generated from the ocean, especially tidal currents using the tidal stream designs but also from the major thermal current systems such as the Gulf Stream, which is covered by the more general term marine current power. Tidal stream turbines may be arrayed in high-velocity areas where natural tidal current flows are concentrated such as the west and east coasts of Canada, the Strait of Gibraltar, the Bosporus, and numerous sites in south east Asia and Australia. Such flows occur almost anywhere where there are entrances to bays and rivers, or between land masses where water currents are concentrated.

Tidal stream generators

A relatively new technology, tidal stream generators draw energy from currents in much the same way as wind turbines. The higher density of water, 832 times the density of air, means that a single generator can provide significant power at low tidal flow velocities (compared with wind speed). Given that power varies with the density of medium and the cube of velocity, it is simple to see that water speeds of nearly one-tenth of the speed of wind provide the same power for the same size of turbine system. However this limits the application in practice to places where the tide moves at speeds of at least 2 knots (1m/s) even close to neap tides.

Since tidal stream generators are an immature technology (no commercial scale production facilities are yet routinely supplying power), no standard technology has yet emerged as the clear winner, but a large variety of designs are being experimented with, some very close to large scale deployment. Several prototypes have shown promise with many companies making bold claims, some of which are yet to be independently verified, but they have not operated commercially for extended periods to establish performances and rates of return on investments.

Engineering approaches

The European Marine Energy Centre[4] categorises them under four heads:

A number of other approaches are being tried.

1. Horizontal axis turbines. These are close in concept to traditional windmills operating under the sea and have the most prototypes currently operating. These include:

Kvalsund, south of Hammerfest, Norway.[5] Although still a prototype, a turbine, generating 300 kW, started supplying power to the community on November 13, 2003.

A 300 kW Periodflow marine current propeller type turbine was tested off the coast of Devon, England in 2003.

Since April 2007 Verdant Power[6] has been running a prototype project in the East River between Queens and Roosevelt Island in New York City; it is the first major tidal-power project in the United States.[7] The strong currents pose challenges to the design: the blades of the 2006 and 2007 prototypes broke off, and new reinforced turbines were installed in September 2008.[8][9]

A fullsize prototype, called SeaGen, has been installed by Marine Current Turbines Ltd in Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland in April 2008. The turbine is expected to generate 1.2 MW and was reported to have fed 150kW into the grid for the first time on July 17, 2008.[10] It is currently the only commercial scale device to have been installed anywhere in the world.[11]

OpenHydro an Irish based company, exploiting the Open-Centre Turbine developed in the US, has a prototype being tested at the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC), in Orkney, Scotland.

2. Vertical axis turbines. The Gorlov turbine[12] is an improved helical design which is being prototyped on a large scale in S. Korea.[13] Neptune Renewable Energy has developed Proteus[14] which uses a barrage of vertical axis crossflow turbines for use mainly in estuaries.

3. Oscillating devices. These don't use rotary devices at all but rather aerofoil sections which are pushed sideways by the flow.

Oscillating stream power extraction was proven with the omni or bi-directional Wing'd Pump windmill[15]

During 2003 a 150kW oscillating hydroplane device, the Stingray, was tested off the Scottish coast.[16]

4. Venturi effect. This uses a shroud to increase the flow rate through the turbine. These can be mounted horizontally or vertically.

The Australian company Tidal Energy Pty Ltd undertook successful commercial trials of highly efficient shrouded tidal turbines on the Gold Coast, Queensland in 2002.

Tidal Energy Pty Ltd has commenced a rollout of their shrouded turbine for a remote Australian community in northern Australia where there are some of the fastest flows ever recorded (11 m/s, 21 knots) – two small turbines will provide 3.5 MW.

Another larger 5 meter diameter turbine, capable of 800 kW in 4 m/s of flow, is planned for deployment as a tidal powered desalination showcase near Brisbane Australia in October 2008.

Another device, the Hydro Venturi, is to be tested in San Francisco Bay.[17]

In late April 2008, Ocean Renewable Power Company, LLC (ORPC) [4] successfully completed the testing of its proprietary turbine-generator unit (TGU) prototype at ORPC’s Cobscook Bay and Western Passage tidal sites near Eastport, Maine.[18] The TGU is the core of the OCGen™ technology and utilizes advanced design cross-flow (ADCF) turbines to drive a permanent magnet generator located between the turbines and mounted on the same shaft. ORPC has developed TGU designs that can be used for generating power from river, tidal and deep water ocean currents.

Trials in the Strait of Messina, Italy, started in 2001 of the Kobold concept.[19]

Commercial plans

RWE's npower announced that it is in partnership with Marine Current Turbines to build a tidal farm of SeaGen turbines off the coast of Anglesey in Wales.[20]

In November 2007, British company Lunar Energy announced that, in conjunction with E.ON, they would be building the world's first tidal energy farm off the coast of Pembrokshire in Wales. It will be the world's first deep-sea tidal-energy farm and will provide electricity for 5,000 homes. Eight underwater turbines, each 25 metres long and 15 metres high, are to be installed on the sea bottom off St David's peninsula. Construction is due to start in the summer of 2008 and the proposed tidal energy turbines, described as "a wind farm under the sea", should be operational by 2010.

British Columbia Tidal Energy Corp. plans to deploy at least three 1.2 MW turbines in the Campbell River or in the surrounding coastline of British Columbia by 2009.[21]

Nova Scotia Power has selected OpenHydro's turbine for a tidal energy demonstration project in the Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia, Canada and Alderney Renewable Energy Ltd for the supply of tidal turbines in the Channel Islands. Open Hydro

Energy calculations

Various turbine designs have varying efficiencies and therefore varying power output. If the efficiency of the turbine "Cp" is known the equation below can be used to determine the power output.

The energy available from these kinetic systems can be expressed as:

- P = Cp x 0.5 x ρ x A x V³[22]

where:

- Cp is the turbine coefficient of performance

- P = the power generated (in watts)

- ρ = the density of the water (seawater is 1025 kg/m³)

- A = the sweep area of the turbine (in m²)

- V³ = the velocity of the flow cubed (i.e. V x V x V)

Relative to an open turbine in free stream, shrouded turbines are capable of efficiencies as much as 3 to 4 times the power of the same turbine in open flow.[22]

Potential sites

As with wind power, selection of location is important for the tidal turbine. Tidal stream systems need to be located in areas with fast currents where natural flows are concentrated between obstructions, for example at the entrances to bays and rivers, around rocky points, headlands, or between islands or other land masses. The following potential sites have been suggested:

- Cook Inlet in Alaska

- Pentland Firth in Scotland

- Dee estuary in Wales

- Pembrokeshire in Wales[23]

- River Severn between Wales and England[24]

- Solway estuary (Morecambe Bay) in England

- Humber estuary in England

- Mersey river in England

- Channel Islands in the English Channel, off the French coast

- Cook Strait[25] in New Zealand

- Strait of Gibraltar

- Bosporus in Turkey

- Bass Strait in Australia

- Torres Strait in Australia

- Strait of Malacca between Indonesia and Singapore

- Bay of Fundy[26] in Canada.

- East River[27][28] in New York City

- Vancouver Island in Canada

- Strait of Magellan south of mainland Chile

- Golden Gate in the San Francisco Bay[29]

- Piscataqua River in New Hampshire[30]

Barrage tidal power

With only three operating plants globally (a large 240 MW plant on the Rance River, and two small plants, one on the Bay of Fundy and the other across a tiny inlet in Kislaya Guba Russia), the barrage method of extracting tidal energy involves building a barrage across a bay or river as in the case of the Rance tidal power plant in France. Turbines installed in the barrage wall generate power as water flows in and out of the estuary basin, bay, or river. These systems are similar to a hydro dam that produces Static Head or pressure head (a height of water pressure). When the water level outside of the basin or lagoon changes relative to the water level inside, the turbines are able to produce power. The largest such installation has been working on the Rance river, France, since 1966 with an installed (peak) power of 240 MW, and an annual production of 600 GWh (about 68 MW average power).

The basic elements of a barrage are caissons, embankments, sluices, turbines, and ship locks. Sluices, turbines, and ship locks are housed in caissons (very large concrete blocks). Embankments seal a basin where it is not sealed by caissons.

The sluice gates applicable to tidal power are the flap gate, vertical rising gate, radial gate, and rising sector.

Barrage systems are affected by problems of high civil infrastructure costs associated with what is in effect a dam being placed across estuarine systems, and the environmental problems associated with changing a large ecosystem.

Ebb generation

The basin is filled through the sluices until high tide. Then the sluice gates are closed. (At this stage there may be "Pumping" to raise the level further). The turbine gates are kept closed until the sea level falls to create sufficient head across the barrage, and then are opened so that the turbines generate until the head is again low. Then the sluices are opened, turbines disconnected and the basin is filled again. The cycle repeats itself. Ebb generation (also known as outflow generation) takes its name because generation occurs as the tide changes tidal direction.

Flood generation

The basin is filled through the turbines, which generate at tide flood. This is generally much less efficient than ebb generation, because the volume contained in the upper half of the basin (which is where ebb generation operates) is greater than the volume of the lower half (filled first during flood generation). Therefore the available level difference — important for the turbine power produced — between the basin side and the sea side of the barrage, reduces more quickly than it would in ebb generation. Rivers flowing into the basin may further reduce the energy potential, instead of enhancing it as in ebb generation. Which of course is not a problem with the "lagoon" model, without river inflow.

Pumping

Turbines are able to be powered in reverse by excess energy in the grid to increase the water level in the basin at high tide (for ebb generation). This energy is more than returned during generation, because power output is strongly related to the head. If water is raised 2 ft (61 cm) by pumping on a high tide of 10 ft (3 m), this will have been raised by 12 ft (3.7 m) at low tide. The cost of a 2 ft rise is returned by the benefits of a 12 ft rise.

Two-basin schemes

Another form of energy barrage configuration is that of the dual basin type. With two basins, one is filled at high tide and the other is emptied at low tide. Turbines are placed between the basins. Two-basin schemes offer advantages over normal schemes in that generation time can be adjusted with high flexibility and it is also possible to generate almost continuously. In normal estuarine situations, however, two-basin schemes are very expensive to construct due to the cost of the extra length of barrage. There are some favourable geographies, however, which are well suited to this type of scheme.

Environmental impact

The placement of a barrage into an estuary has a considerable effect on the water inside the basin and on the ecosystem. Many governments have been reluctant in recent times to grant approval for tidal barrages. Environmental impacts of tidal plants in the United States are difficult to measure because there are currently no US tidal plants. However, through research conducted on tidal plants in other parts of the world, it has been found that tidal barrages constructed at the mouths of estuaries pose similar environmental threats as large dams. The construction of large tidal plants alters the flow of saltwater in and out of estuaries, which changes the hydrology and salinity and possibly negatively affects the marine mammals that use the estuaries as their habitat [31] The La Rance plant, off the Brittany coast of northern France, was the first and largest tidal barrage plant in the world. It is also the only site where a full-scale evaluation of the ecological impact of a tidal power system, operating for 20 years, has been made [32]

French researchers found that the isolation of the estuary during the construction phases of the tidal barrage was detrimental to flora and fauna, however; after ten years, there has been a “variable degree of biological adjustment to the new environmental conditions” [32]

Some species lost their habitat due to La Rance’s construction, but other species colonized the abandoned space, which caused a shift in diversity. Also as a result of the construction, sandbanks disappeared, the beach of St. Servan was badly damaged and high-speed currents have developed near sluices, which are water channels controlled by gates [33]

Turbidity

Turbidity (the amount of matter in suspension in the water) decreases as a result of smaller volume of water being exchanged between the basin and the sea. This lets light from the Sun to penetrate the water further, improving conditions for the phytoplankton. The changes propagate up the food chain, causing a general change in the ecosystem.

Tidal Fences and Turbines

Tidal fences and turbines can have varying environmental impacts depending on whether or not fences and turbines are constructed with regard to the environment. The main environmental impact of turbines is their impact on fish. If the turbines are moving slowly enough, such as low velocities of 25-50 rpm, fish kill is minimalized and silt and other nutrients are able to flow through the structures [34] For example, a 20kW tidal turbine prototype built in the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1983 reported no fish kills [34] Tidal fences block off channels, which makes it difficult for fish and wildlife to migrate through those channels. In order to reduce fish kill, fences could be engineered so that the spaces between the caisson wall and the rotor foil are large enough to allow fish to pass through [34] Larger marine mammals such as seals or dolphins can be protected from the turbines by fences or a sonar sensor auto-breaking system that automatically shuts the turbines down when marine mammals are detected [34] Overall, many researches have argued that while tidal barrages pose environmental threats, tidal fences and tidal turbines, if constructed properly, are likely to be more environmentally benign. Unlike barrages, tidal fences and turbines do not block channels or estuarine mouths, interrupt fish migration or alter hydrology, thus, these options offer energy generating capacity without dire environmental impacts [34]

Salinity

As a result of less water exchange with the sea, the average salinity inside the basin decreases, also affecting the ecosystem. "Tidal Lagoons" do not suffer from this problem.

Sediment movements

Estuaries often have high volume of sediments moving through them, from the rivers to the sea. The introduction of a barrage into an estuary may result in sediment accumulation within the barrage, affecting the ecosystem and also the operation of the barrage.

Fish

Fish may move through sluices safely, but when these are closed, fish will seek out turbines and attempt to swim through them. Also, some fish will be unable to escape the water speed near a turbine and will be sucked through. Even with the most fish-friendly turbine design, fish mortality per pass is approximately 15% (from pressure drop, contact with blades, cavitation, etc.). Alternative passage technologies (fish ladders, fish lifts, etc.) have so far failed to solve this problem for tidal barrages, either offering extremely expensive solutions, or ones which are used by a small fraction of fish only. Research in sonic guidance of fish is ongoing. The Open-Centre turbine reduces this problem allowing fish to pass through the open centre of the turbine.

Recently a run of the river type turbine has been developed in France. This basically is a very large slow rotating Kaplan type turbine mounted on an angle. Testing for fish mortality has indicated much lower mortality figures, less than 5%. This concept seems very suitable for adaption to marine current/tidal turbines also.[35]

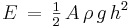

Energy calculations

The energy available from barrage is dependent on the volume of water. The potential energy contained in a volume of water is:[36]

where:

- h is the vertical tidal range,

- A is the horizontal area of the barrage basin,

- ρ is the density of water = 1025 kg per cubic meter (seawater varies between 1021 and 1030 kg per cubic meter) and

- g is the acceleration due to the Earth's gravity = 9.81 meters per second squared.

The factor half is due to the fact, that as the basin flows empty through the turbines, the hydraulic head over the dam reduces. The maximum head is only available at the moment of low water, assuming the high water level is still present in the basin.

Example calculation of tidal power generation

Assumptions:

- Let us assume that the tidal range of tide at a particular place is 32 feet = 10 m (approx)

- The surface of the tidal energy harnessing plant is 9 km² (3 km × 3 km)= 3000 m × 3000 m = 9 × 106 m2

- Specific density of sea water = 1025.18 kg/m3

Mass of the water = volume of water × specific gravity

-

- = (area × tidal range) of water × mass density

- = (9 × 106 m2 × 10 m) × 1025.18 kg/m3

- = 92 × 109 kg (approx)

Potential energy content of the water in the basin at high tide = ½ × area × density × gravitational acceleration × tidal range squared

-

- = ½ × 9 × 106 m2 × 1025 kg/m3 × 9.81 m/s2 × (10 m)2

- =4.5 × 1012 J (approx)

Now we have 2 high tides and 2 low tides every day. At low tide the potential energy is zero.

Therefore the total energy potential per day = Energy for a single high tide × 2

-

- = 4.5 × 1012 J × 2

- = 9 × 1012 J

Therefore, the mean power generation potential = Energy generation potential / time in 1 day

-

- = 9 × 1012 J / 86400 s

- = 104 MW

Assuming the power conversion efficiency to be 30%: The daily-average power generated = 104 MW * 30% / 100%

-

- = 31 MW (approx)

A barrage is best placed in a location with very high-amplitude tides. Suitable locations are found in Russia, USA, Canada, Australia, Korea, the UK. Amplitudes of up to 17 m (56 ft) occur for example in the Bay of Fundy, where tidal resonance amplifies the tidal range.

Economics

Tidal barrage power schemes have a high capital cost and a very low running cost. As a result, a tidal power scheme may not produce returns for many years, and investors may be reluctant to participate in such projects.

Governments may be able to finance tidal barrage power, but many are unwilling to do so also due to the lag time before investment return and the high irreversible commitment. For example the energy policy of the United Kingdom[37] recognizes the role of tidal energy and expresses the need for local councils to understand the broader national goals of renewable energy in approving tidal projects. The UK government itself appreciates the technical viability and siting options available, but has failed to provide meaningful incentives to move these goals forward.

Mathematical modelling of tidal schemes

In mathematical modelling of a scheme design, the basin is broken into segments, each maintaining its own set of variables. Time is advanced in steps. Every step, neighbouring segments influence each other and variables are updated.

The simplest type of model is the flat estuary model, in which the whole basin is represented by one segment. The surface of the basin is assumed to be flat, hence the name. This model gives rough results and is used to compare many designs at the start of the design process.

In these models, the basin is broken into large segments (1D), squares (2D) or cubes (3D). The complexity and accuracy increases with dimension.

Mathematical modelling produces quantitative information for a range of parameters, including:

- Water levels (during operation, construction, extreme conditions, etc.)

- Currents

- Waves

- Power output

- Turbidity

- Salinity

- Sediment movements

Global environmental impact

A tidal power scheme is a long-term source of electricity. A proposal for the Severn Barrage, if built, has been projected to save 18 million tonnes of coal per year of operation. This decreases the output of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

If fossil fuel resources decline during the 21st century, as predicted by Hubbert peak theory, tidal power is one of the alternative sources of energy that will need to be developed to satisfy the human demand for energy.

Operating tidal power schemes

- The first tidal power station was the Rance tidal power plant built over a period of 6 years from 1960 to 1966 at La Rance, France.[38] It has 240 MW installed capacity.

- The first tidal power site in North America is the Annapolis Royal Generating Station, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, which opened in 1984 on an inlet of the Bay of Fundy.[39] It has 18 MW installed capacity.

- The first in- stream tidal current generator in North America (Race Rocks Tidal Power Demonstration Project) was installed at [(Race Rocks)] on Southern Vancouver Island in September 2006.[40][41] The [(next phase in the development)][42] of this tidal current generator will be in Nova Scotia.

- A small project was built by the Soviet Union at Kislaya Guba on the Barents Sea. It has 0.5 MW installed capacity. In 2006 it was upgraded with 1.2MW experimental advanced orthogonal turbine.

- Another 12MW project at Kislaya Guba in Russia with orthogonal turbines is under construction.

- China has apparently developed several small tidal power projects and one large facility in Jiangxia.

- China is also developing a tidal lagoon near the mouth of the Yalu.[43]

- Scotland has committed to having 18% of its power from green sources by 2010, including 10% from a tidal generator. The British government says this will replace one huge fossil fuelled power station.[44]

- South African energy parastatal Eskom is investigating using the Mozambique Current to generate power off the coast of KwaZulu Natal. Because the continental shelf is near to land it may be possible to generate electricity by tapping into the fast flowing Mozambique current.[45]

Tidal power schemes being considered

In the table, "-" indicates missing information, "?" indicates information which has not been decided

| Country | Place | Mean tidal range (m) | Area of basin (km²) | Maximum capacity (MW) |

| Argentina | San Jose | 5.9 | - | 6800 |

| Australia | Secure Bay | 10.9 | - | ? |

| Canada | Cobequid | 12.4 | 240 | 5338 |

| Cumberland | 10.9 | 90 | 1400 | |

| Shepody | 10.0 | 115 | 1800 | |

| Passamaquoddy | 5.5 | - | ? | |

| India | Kutch | 5.3 | 170 | 900 |

| Cambay | 6.8 | 1970 | 7000 | |

| South Korea | Garolim | 4.7 | 100 | 480 |

| Cheonsu | 4.5 | - | - | |

| Mexico | Rio Colorado | 6-7 | - | ? |

| Tiburon | - | - | ? | |

| United Kingdom | River Severn | 7.8 | 450 | 8640 |

| River Mersey | 6.5 | 61 | 700 | |

| Strangford Lough | - | - | - | |

| Conwy | 5.2 | 5.5 | 33 | |

| United States | Passamaquoddy Bay, Maine | 5.5 | - | ? |

| Knik Arm, Alaska | 7.5 | - | 2900 | |

| Turnagain Arm, Alaska | 7.5 | - | 6501 | |

| Golden Gate, California[46] | ? | - | ? | |

| Russia[47] | Mezen | 9.1 | 2300 | 19200 |

| Tugur | - | - | 8000 | |

| Penzhinskaya Bay[48][49] | 6.0 | 20,500 | 87,000 | |

| South Africa | Mozambique Channel | ? | ? | ? |

| New Zealand | Kaipara Harbour | 2.10 | 947 | 200+ |

See also

- Category:Energy by country

- Run-of-the-river hydroelectricity

- Damless hydro

- Marine current power

- Ocean energy

- Wave power

- World energy resources and consumption

References

- Baker, A. C. 1991, Tidal power, Peter Peregrinus Ltd., London.

- Baker, G. C., Wilson E. M., Miller, H., Gibson, R. A. & Ball, M., 1980. "The Annapolis tidal power pilot project", in Waterpower '79 Proceedings, ed. Anon, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, pp 550-559.

- Hammons, T. J. 1993, "Tidal power", Proceedings of the IEEE, [Online], v81, n3, pp 419-433. Available from: IEEE/IEEE Xplore. [July 26, 2004].

- Lecomber, R. 1979, "The evaluation of tidal power projects", in Tidal Power and Estuary Management, eds. Severn, R. T., Dineley, D. L. & Hawker, L. E., Henry Ling Ltd., Dorchester, pp 31-39.

Notes

- ↑ Spain, Rob: "A possible Roman Tide Mill", Paper submitted to the Kent Archaeological Society

- ↑ Minchinton, W. E. (Oct. 1979). "Early Tide Mills: Some Problems". Technology and Culture 20 (4): 777–786. doi:.

- ↑ George E. Williams. "Geological constraints on the Precambrian history of Earth's rotation and the Moon's orbit". Reviews of Geophysics 38 (2000), 37-60.

- ↑ EMEC. "Tidal Energy Devices". Retrieved on 5 Oct 2008.

- ↑ First power station to harness Moon opens - September 22, 2003 - New Scientist

- ↑ Verdant Power

- ↑ MIT Technology Review, April 2007 Accessed August 24, 2008]

- ↑ Robin Shulman (September 20, 2008). "N.Y. Tests Turbines to Produce Power. City Taps Current Of the East River". Washington Post. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Kate Galbraith (September 22, 2008). "Power From the Restless Sea Stirs the Imagination". New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ First connection to the grid

- ↑ · Sea Generation Tidal Turbine

- ↑ Gorlov Turbine

- ↑ Gorlov Turbines in Koreas

- ↑ Proteus

- ↑ Wing'd Pump Windmill

- ↑ Stingray

- ↑ San Francisco Bay Guardian News

- ↑ "Tide is slowly rising in interest in ocean power". Mass High Tech: The Journal of New England Technology (August 1, 2008). Retrieved on 2008-10-11.

- ↑ A.D.A.Group

- ↑ RWE plans 10.5 MW sea current power plant off Welsh coast - Forbes.com

- ↑ Tidal Power Coming to West Coast of Canada

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 http://www.cyberiad.net/library/pdf/bk_tidal_paper25apr06.pdf tidal paper on cyberiad.net

- ↑ Builder & Engineer - Pembrokeshire tidal barrage moves forward

- ↑ Severn balancing act

- ↑ NZ: Chance to turn the tide of power supply | EnergyBulletin.net | Peak Oil News Clearinghouse

- ↑ Bay of Fundy to get three test turbines | Cleantech.com

- ↑ Shulman, Robin (September 20, 2008). "N.Y. Tests Turbines to Produce Power", The Washington Post. ISSN 0740-5421. Retrieved on 2008-09-20.

- ↑ Verdant Power

- ↑ http://deanzaemtp.googlepages.com/PGEbacksnewstudyofbaystidalpower.pdf

- ↑ Tidal power from Piscataqua River?

- ↑ Pelc, Robin and Fujita, Rob. Renewable energy from the ocean.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 [ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WBR-45P0YSY-18&_user=607017&_coverDate=01%2F31%2F1994&_alid=807589306&_rdoc=7&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_cdi=6717&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_ct=13&_acct=C000031527&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=607017&md5=a1bf5bed8436ee57584961d337274b71 Retiere, C. Tidal power and aquatic environment of La Rance. ]

- ↑ [ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VMY-4K7FFMT-1&_user=607017&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F2007&_alid=807601279&_rdoc=2&_fmt=high&_orig=mlkt&_cdi=6163&_sort=v&_st=17&_docanchor=&view=c&_ct=743&_acct=C000031527&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=607017&md5=3cedbf77e95163ad11903503d4f6775e Charlier, Roger. Forty candles for the Rance River TPP tides provide renewable and sustainable power generation]

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Pelc, Robin and Fujita, Rob. Renewable energy from the ocean.

- ↑ VLH TURBINE

- ↑ Lamb, H. (1994). Hydrodynamics (6th edition ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458689. §174, p. 260.

- ↑ [1] (see for example key principles 4 and 6 within Planning Policy Statement 22)

- ↑ L'Usine marémotrice de la Rance

- ↑ Nova Scotia Power - Environment - Green Power- Tidal

- ↑ Race Rocks Demonstration Project

- ↑ Tidal Energy, Ocean Energy

- ↑ Information for media inquiries

- ↑ China Endorses 300 MW Ocean Energy Project

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Independent Online Article

- ↑ Potential Power Source: The Ocean?

- ↑ http://www.elektropages.ru/article/4_2006_ELEKTRO.html

- ↑ Russian power plants soon to utilize tidal energy :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ↑ http://www.severnestuary.net/sep/pdfs/managingtidalchangeprojectreport-phase1final.pdf

External links

- Climate Change Chronicles -- Article about new tidal power technology

- Location of Potential Tidal Stream Power sites in the UK

- University of Strathclyde ESRU -- Summary of tidal and marine current generators

- University of Strathclyde ESRU-- Detailed analysis of marine energy resource, current energy capture technology appraisal and environmental impact outline

- Coastal Research - Foreland Point Tidal Turbine and warnings on proposed Severn Barrage

- The British Library - finding information on the renewable energy industry

- Independent Online - information about South African ventures into coastal current power

- State explores renewable energy powered by tides

- Sustainable Development Commission - Report looking at 'Tidal Power in the UK', including proposals for a Severn barrage

- World Energy Council - Report on Tidal Energy

|

||||||||||||||||||||