Road

A road is an identifiable route, way or path between places.[1] Roads are typically smoothed, paved, or otherwise prepared to allow easy travel;[2] though they need not be, and historically many roads were simply recognizable routes without any formal construction or maintenance.[3]

The term was also commonly used to refer to roadsteads, waterways that lent themselves to use by shipping. Notable examples being Hampton Roads, in Virginia, and Castle Roads, in Bermuda (also formerly in Virginia).

In urban areas roads may diverge through a city or village and be named as streets, serving a dual function as urban space easement and route.[4] Economics and society depend heavily on efficient roads. In the European Union (EU) 44% of all goods are moved by trucks over roads and 85% of all persons are transported by cars, buses or coaches on roads.[5]

The United States has the largest network of roadways of any country with 6,430,366 km (2005). India has the second largest road system in the world with 3,383,344 km (2002). People's Republic of China is third with 1,870,661 km of roadway (2004).[6] When looking only at expressways the National Trunk Highway System (NTHS) in People's Republic of China has a total length of 45,000 km at the end of 2006, second only to the United States with 90,000 km in 2005.[7][8]

Contents |

History

- See also: History of road transport

That the first pathways were the trails made by animals has not been universally accepted, arguing that animals do not follow constant paths.[3] Others believe that some roads originated from humans following animal trails.[9][10] The Icknield Way is given as an example of this type road origination, where man and animal both selected the same natural line.[11] By about 10,000 BC, rough pathways were used by human travelers.[3]

Historical road construction dating to 4000 BC

- Stone paved streets are found in the city of Ur in the Middle East dating back to 4000 BC[3]

- Corduroy roads (log roads) are found dating to 4,000 BC in Glastonbury, England[3]

- The timber trackway; Sweet Track causeway in England, is one of the oldest engineered roads discovered and the oldest timber trackway discovered in Northern Europe. Built in winter 3807 BC or spring 3806 BC, tree-ring dating (Dendrochronology) enabled very precise dating. It has been claimed to be the oldest road in the world.[12][13]

- In 500 BC, Darius I the Great started an extensive road system for Persia (Iran), including the famous Royal Road which was one of the finest highways of its time.[14] The road remained in use after Roman times.

- In ancient times, transport by river was far easier and faster than transport by road,[13] especially considering the cost of road construction and the difference in carrying capacity between carts and river barges. A hybrid of road transport and ship transport beginning in about 1740 is the horse-drawn boat in which the horse follows a cleared path along the river bank.[15][16]

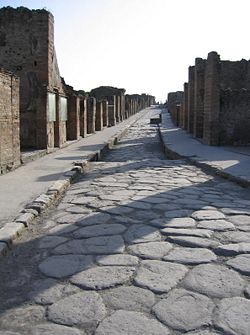

- From about 312 BC, the Roman Empire built straight[17] strong stone Roman roads throughout Europe and North Africa, in support of its military campaigns. At its peak the Roman Empire was connected by 29 major roads moving out from Rome and covering 78,000 kilometers or 52,964 Roman miles of paved roads.[13]

- In the 700s AD, many roads were built throughout the Arab Empire. The most sophisticated roads were those of the Baghdad, Iraq, which were paved with tar in the 8th century. Tar was derived from petroleum, accessed from oil fields in the region, through the chemical process of destructive distillation.[18]

- In the 1600s road construction and maintenance in Britain was traditionally done on a local parish basis.[13] This resulted in a poor and variable state of roads. To remedy this, the first of the "Turnpike Trusts" was established around 1706, to build good roads and collect tolls from passing vehicles. Eventually there were approximately 1,100 Trusts in Britain and some 36,800 km of engineered roads.[13] The Rebecca Riots in Carmarthenshire and Rhayader from 1839 to 1844 contributed to a Royal Commission leading to the demise of the system in 1844.[19]

Road transport economics

Transport economics is a branch of economics that deals with the allocation of resources within the transport sector and has strong linkages with civil engineering. Transport economics differs from some other branches of economics in that the assumption of a spaceless, instantaneous economy does not hold. People and goods flow over networks at certain speeds. Demands peak. Advanced ticket purchase is often induced by lower fares. The networks themselves may or may not be competitive. A single trip (the final good from the point-of-view of the consumer) may require bundling the services provided by several firms, agencies and modes.

Although transport systems follow the same supply and demand theory as other industries, the complications of network effects and choices between non-similar goods (e.g. car and bus travel) make estimating the demand for transportation facilities difficult. The development of models to estimate the likely choices between the non-similar goods involved in transport decisions "discrete choice" models led to the development of the important branch of econometrics, and a Nobel Prize for Daniel McFadden.[20]

In transport, demand can be measured in numbers of journeys made or in total distance traveled across all journeys (e.g. passenger-kilometres for public transport or vehicle-kilometres of travel (VKT) for private transport). Supply is considered to be a measure of capacity. The price of the good (travel) is measured using the generalised cost of travel, which includes both money and time expenditure. The effect of increases in supply (capacity) are of particular interest in transport economics (see induced demand), as the potential environmental consequences are significant.

Road building and maintenance is an area of economic activity that remains dominated by the public sector (though often through private contractors).[21] Roads (except those on private property that are not accessible to the general public) are typically paid for by taxes (often raised through levies on fuel),[22] though some public roads, especially freeways are funded by tolls.[23]

Environmental aspects

Motor vehicle traffic on roads generate noise pollution especially at higher operating speeds, near intersections and on uphill sections. Therefore, considerable noise health effects are expected from road systems used by large numbers of motor vehicles. Noise mitigation strategies exist to reduce sound levels at nearby sensitive receptors. The idea that road design could be influenced by acoustical engineering considerations first arose about 1973.[24]

Motor vehicles operating on roads contribute emissions, particularly for congested city street conditions and other low speed circumstances. Of particular concern are particulate emmissions from diesel engines. Concentrations of air pollutants and adverse respiratory health effects are greater near the road than at some distance away from the road. [25] Road dust dust kicked up by vehicles may trigger allergic reactions.[26]

De-icing chemicals and sand can run off into roadsides. Road salts (primarily chlorides of sodium, calcium or magnesium) can be toxic to sensitive plants and animals. Sand can alter stream bed environments, causing stress for the plants and animals that live there. Traffic can grind sand into fine particulates and contribute to air pollution.

Driving on the right or the left

Traffic flows on the right or on the left side of the road depending on the country.[27] In countries where traffic flows on the right, traffic signs are mostly on the right side of the road, roundabouts and traffic circles go counter-clockwise, and pedestrians crossing a two-way road should watch out for traffic from the left first.[28] In countries where traffic flows on the left, the reverse is true.

About 34% of the world by population drive on the left, and 66% keep right. By roadway distances, about 28% drive on the left, and 72% on the right,[29] even though originally most traffic drove on the left worldwide.[30]

Construction

Road construction requires the creation of a continuous right-of-way, overcoming geographic obstacles and having grades low enough to permit vehicle or foot travel.[31] (pg15) and may be required to meet standards set by law[32] or official guidelines.[33] The process is often begun with the removal of earth and rock by digging or blasting, construction of embankments, bridges and tunnels, and removal of vegetation (this may involve deforestation) and followed by the laying of pavement material. A variety of road building equipment is employed in road building.[34] [35]

After design, approval, planning, legal and environmental considerations have been addressed alignment of the road is set out by a surveyor. [17] The Radii and gradient are designed and staked out to best suit the natural ground levels and minimize the amount of cut and fill.[33] (page34) Great care is taken to preserve reference Benchmarks [33] (page59)

Roadways are designed and built for primary use by vehicular and pedestrian traffic. Storm drainage and environmental considerations are a major concern. Erosion and sediment controls are constructed to prevent detrimental effects. Drainage lines are laid with sealed joints in the road easement with runoff coefficients and characteristics adequate for the land zoning and storm water system. Drainage systems must be capable of carrying the ultimate design flow from the upstream catchment with approval for the outfall from the appropriate authority to a watercourse, creek, river or the sea for drainage discharge. [33] (page38 to 40)

A Borrow pit (source for obtaining fill, gravel, and rock) and a water source should be located near or in reasonable distance to the road construction site. Approval from local authorities may be required to draw water or for working (crushing and screening) of materials for construction needs. The top soil and vegetation is removed from the borrow pit and stockpiled for subsequent rehabilitation of the extraction area. Side slopes in the excavation area not steeper than one vertical to two horizontal for safety reasons. [33] (page 53 to 56 )

Old road surfaces, fences, and buildings may need to be removed before construction can begin. Trees in the road construction area may be marked for retention. These protected trees should not have the topsoil within the area of the tree's drip line removed and the area should be kept clear of construction material and equipment. Compensation or replacement may be required if a protected tree is damaged. Much of the vegetation may be mulched and put aside for use during reinstatement. The topsoil is usually stripped and stockpiled nearby for rehabilitation of newly constructed embankments along the road. Stumps and roots are removed and holes filled as required before the earthwork begins. Final rehabilitation after road construction is completed will include seeding, planting, watering and other activities to reinstate the area to be consistent with the untouched surrounding areas.[33] (page 66 to 67 )

Processes during earthwork include excavation, removal of material to spoil, filling, compacting, construction and trimming. If rock or other unsuitable material is discovered it is removed, moisture content is managed and replaced with standard fill compacted to 90% relative compaction. Generally blasting of rock is discouraged in the road bed. When a depression must be filled to come up to the road grade the native bed is compacted after the topsoil has been removed. The fill is made by the "compacted layer method" where a layer of fill is spread then compacted to specifications, the process is repeated until the desired grade is reached.[33] (page 68 to 69 )

General fill material should be free of organics, meet minimum California bearing ratio (CBR) results and have a low plasticity index. Select fill (sieved) should be composed of gravel, decomposed rock or broken rock below a specified Particle size and be free of large lumps of clay. Sand clay fill may also be used. The road bed must be "proof rolled" after each layer of fill is compacted. If a roller passes over an area without creating visible deformation or spring the section is deemed to comply. [33] (page 70 to 72 )

The completed road way is finished by paving or left with a gravel or other natural surface. The type of road surface is dependent on economic factors and expected usage. Safety improvements like Traffic signs, Crash barriers, Raised pavement markers, and other forms of Road surface marking are installed.

Duplication

When a single carriageway road is converted into dual carriageway by building a second separate carriageway alongside the first, it is usually referred to as duplication[36] or twinning. The original carriageway is changed from two-way to become one-way, while the new carriageway is one-way in the opposite direction. In the same way as converting railway lines from single track to double track, the new carriageway is not always constructed directly alongside the existing carriageway.

Maintenance

Like all structures, roads deteriorate over time. Deterioration is primarily due to accumulated damage from vehicles, however environmental effects such as frost heaves, thermal cracking and oxidation often contribute.[37] According to a series of experiments carried out in the late 1950s, called the AASHO Road Test, it was empirically determined that the effective damage done to the road is roughly proportional to the 4th power of axle weight .[38] A typical tractor-trailer weighing 80,000 pounds (36.287 t) with 8,000 pounds (3.6287 t) on the steer axle and 36,000 pounds (16.329 t) on both of the tandem axle groups is expected to do 7,800 times more damage than a passenger vehicle with 2,000 pounds (0.907 t) on each axle. Potholes on roads are caused by rain damage and vehicle braking or related construction works.

Pavements are designed for an expected service life or design life. In some UK countries the standard design life is 40 years for new bitumen and concrete pavement. Maintenance is considered in the whole life cost of the road with service at 10, 20 and 30 year milestones. [39] Roads can be and are designed for a variety of lives (8-, 15-, 30-, and 60-year designs). When pavement lasts longer then its intended life, it may have been overbuilt, and the original costs may have been too high. When a pavement fails before its intended design life, the owner may have excessive repair and rehabilitation costs. Many concrete pavements built since the 1950s have significantly outlived their intended design lives. [40] Some roads like Chicago, Illinois's "Wacker Drive", a major two-level viaduct in downtown area are being rebuilt with a designed service life of 100 years. [41]

Virtually all roads require some form of maintenance before they come to the end of their service life. Pro-active agencies continually monitor road conditions and apply preventive maintenance treatments as needed to prolong the lifespan of their roads. Technically advanced agencies monitior the road network surface condition with sophisticated equipment such as laser/inertial Profilometers. These measurements include road curvature, cross slope, unevenness, roughness, rutting and texture (roads). This data is fed into a pavement management system, which recommends the best maintenance or construction treatment to correct the damage that has occurred.

Maintenance treatments for asphalt concrete generally include crack sealing, surface rejuvenating, fog sealing, micro-milling and surface treatments. Thin surfacing preserves, protects and improves the functional condition of the road while reducing the need for routing maintenance, leading to extended service life without increasing structural capacity.[42]

Terminology

- Alignment (road) - Cross slope/Banking/Superelevation, horizontal and vertical curvature of a road.

- All-weather road - Unpaved road that is constructed of a material that does not create mud during rainfall.

- Bollard - Rigid posts that can be arranged in a line to close a road or path to vehicles above a certain width

- Byway - Highway over which the public have a right to travel for vehicular and other kinds of traffic, but which is used mainly as footpaths and bridleways

- Bypass Road that avoids or "bypasses" a built-up area, town, or village

- Bottleneck - Section of a road with a carrying capacity substantially below that of other sections of the same road

- Botts' dots - Non reflective raised pavement marker used on roads

- Cat's eye - reflective raised pavement marker used on roads

- Chicane - Sequence of tight serpentine curves (usually an S-shape curve or a bus stop) in a roadway

- Chipseal - Road surface composed of a thin layer of crushed stone 'chips' and asphalt emulsion. It seals the surface and protects it from weather, but provides no structural strength. It is cheaper than asphalt concrete or a concrete, in the U.S. it is usually only used on low volume rural roads

- Corniche - Road on the side of a cliff or mountain, with the ground rising on one side and falling away on the other

- Curb - Edge where a raised pavement/sidewalk/footpath, road median, or road shoulder meets an unraised street or other roadway.

- Curb extension - (or also kerb extension, bulb-out, nib, elephant ear, curb bulge and blister) Traffic calming measure, intended to slow the speed of traffic and increase driver awareness, particularly in built-up and residential neighborhoods.

- Fork - (literally "fork in the road") Type of intersection where a road splits

- Guard rail - Prevents vehicles from veering off the road into oncoming traffic, crashing against solid objects or falling from a road

- Green lane - (UK) Unsurfaced road, may be so infrequently used that vegetation colonises freely, hence 'green'. Many green lanes are ancient routes that have existed for millennia, similar to a Byway

- Interstate Highway System - United States System of Interstate and Defense Highways

- Median - On divided roads, including expressways, motorways, or autobahns, the central reservation (British English), median (North American English), median strip (North American English and Australian English), neutral ground [Louisiana English] or central nature strip (Australian English) is the area which separates opposing lanes of traffic

- Mountain pass - Lower point that allows easier access through a range of mountains

- Milestone - One of a series of numbered markers placed along a road at regular intervals, showing the distance to destinations.

- Pavement - The road regarded as a geoconstruction.

- Pedestrian crossing - Designated point on a road at which some means are employed to assist pedestrians wishing to cross safely

- Private highway - Highway owned and operated for profit by private industry

- Private road - Road owned and maintained by a private individual, organization, or company rather than by a government

- Public space - Place where anyone has a right to come without being excluded because of economic or social conditions

- Pullout (layby, pull-off) - A paved area beside a main road where cars can stop temporarily to let another car pass.

- Ranch road - U.S. road which serves to connect rural and agricultural areas to market towns

- Road number - Often assigned to a stretch of public roadway. The number chosen is often dependent on the type of road, with numbers differentiating between interstates, motorways, arterial thoroughfares, and so forth

- Road-traffic safety - Process to reduce the harm (deaths, injuries, and property damage) resulting from crashes of road vehicles traveling on public roads

- Roadworks - Part or all of the road has to be occupied for work or maintenance relating to the road

- Roughness - Deviations from a true planar pavement surface, which affects vehicle suspension deflection, dynamic loading, ride quality, surface drainage and winter operations. Roughness have wavelengths ranging from 500 mm up to some 40 m. The upper limit may be as high as 350 m when considering motion sickness aspects; motion sickness is generated by motion with down to 0.1 Hz frequency; in an ambulance car driving 35 m/s (126 km/h), waves with up to 350 m will excite motion sickness.

- Shoulder - Reserved area by the verge of a road, generally it is kept clear of all traffic

- State highway - Road numbered by the state, falling below numbered national highways (like U.S. Routes) in the hierarchy OR A road maintained by the state, including nationally-numbered highways

- Texture (roads) - Deviations from a true planar pavement surface, which affects the interaction between road and tire. Microtexture have wavelengths below 0.5 mm, Macrotexture below 50 mm and Megatexture below 500 mm.

- Traffic calming - Set of strategies used by urban planners and traffic engineers which aim to slow down or reduce traffic, thereby improving safety for pedestrians and bicyclists as well as improving the environment for residents

- Traffic light - also known as a traffic signal, stop light, stop-and-go lights, robot or semaphore, is a signaling device positioned at a road intersection, pedestrian crossing, or other location in order to assign right of way to different approaches to an intersection

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ "Major Roads of the United States". NationalAtlas.gov, Map Layer Info. United States Department of the Interior (March 13, 2006). Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ "Road Infrastructure Strategic Framework for South Africa". A Discussion Document. National Department of Transport (South Africa). Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Lay, Maxwell G (1992). Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles that Used Them. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813526914. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0813526914&id=flvS-nJga8QC&pg=PR3&lpg=PR3&ots=DvEHtwROGm&dq=%22Ways+of+the+world%22+Rutgers+University+Press,+New+Brunswick&sig=tK2dgY-CJ8S2DSeTaMJKKi82Uew#PPA6,M1.

- ↑ "What is the difference between a road and a street?". Word FAQ. Dictionary.com (Lexico Publishing Group, LLC) (2007). Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ "Road Transport (Europe)". Overview. European Communities, Transportation (2007-02-15). Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2085rank.html, CIA World Factbook

- ↑ China to build more highways in 2007

- ↑ Expressways Being Built at Frenetic Pace

- ↑ (PDF)Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 2001, volume 28 (Self-organizing pedestrian movement). pp. 376. doi:. http://pedsim.elte.hu/pdf/envplanb.pdf.

- ↑ "Marshalls Heath Nature Reserve". History. wheathampstead.net (24 February 2003). Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ "The Icknield Way Path". Icknield Way Association (2004). Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ↑ "The Somerset Levels (the oldest timber trackway discovered in Northern Europe)". Current Archaeology 172. Current Archaeology (February 2001). Retrieved on 2007-03-25.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 O'Flaherty, Coleman A. (2002). Highways: The Location, Design, Construction & Maintenance of Road Pavements. Elsevier. ISBN 0750650907. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0750650907&id=Ren4sWQ3jKkC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=ancient+Egyptians+stone+paved+road++Great+Pyramid+in+about+3000+BC&sig=c1OaZDxjJjjOlWtkM-8h1m3niCo#PPA2,M1.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. "Royal Road". History of Iran. Iran Chamber of Society. Retrieved on 2007-04-09.

- ↑ "Horseboating" (Web). The Horseboating Society. Retrieved on 2007-04-09.

- ↑ "Horses and Canals 1760 - 1960 The people & the horses". Horse Drawn Boats. Canal Junction Ltd. Retrieved on 2007-04-09.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hart-Davis, Adam (2001-06-01). "Roads and surveying". Discovering Roman Technology. BBC.CO.UK. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ↑ Dr. Kasem Ajram (1992). The Miracle of Islam Science (2nd Edition ed.). Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0-911119-43-4.

- ↑ "The Rebecca Riots". Rebecca and her daughters come to Rhayader. Victorian Powys for Schools (March 2002). Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2000". Daniel L. McFadden "for his development of theory and methods for analyzing discrete choice". Nobel Foundation (2000). Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Author = www.stat-usa.gov/ (2006-02-28). "International Market Research Reports". Australia CCG 2004 Update: Economic Trends and Outlook (E. INFRASTRUCTURE ). Industry Canada. Retrieved on 2007-04-17.

- ↑ "State and Federal Gasoline Taxes". Maps, Reports and history of gas tax in the United States. American Road & Transportation Builders Association ("ARTBA"). Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ "International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association" (April 16, 2007). Retrieved on 2007-04-17.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, Analysis of highway noise, Journal of Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, Volume 2, Number 3, Biomedical and Life Sciences and Earth and Environmental Science Issue, Pages 387-392, September, 1973, Springer Verlag, Netherlands ISSN 0049-6979

- ↑ "Traffic-related Air Pollution near Busy Roads". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol 170. pp. 520-526 (2004).

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/11/991130062843.htm

- ↑ "Why In Britain Do We Drive On The Left?". 2Pass.co.uk (© 1996-2007). Retrieved on 2007-03-24.

- ↑ Kincaid, Peter (1986). The Rule of the Road: An International Guide to History and Practice. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25249-1. http://www.amazon.com/Rule-Road-International-History-Practice/dp/0313252491.

- ↑ Lucas, Brian (2005). "Which side of the road do they drive on?". Retrieved on 2006-08-03.

- ↑ "Why do some countries drive on the right and others on the left?".

- ↑ "Kitsap County Road Standards 2006" (Doc). Kitsap County, Washington (2006). Retrieved on 2007-04-20.

- ↑ "Washington State County Road Standards". Chapter 35.78 RCW requires cities and counties to adopt uniform definitions and design standards for municipal streets and roads. Municipal Research & Services Center of Washington (2005). Retrieved on 2007-04-20.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 Shire of Wyndham East Kimberly (October 2006). "Guidelines for rural road design and construction technical specifications" (PDF). Western Australia (The Last Frontier). Retrieved on 2007-04-24.

- ↑ "Road Building Equipment". Constructing roads into forestry work areas. Caterpillar (2007). Retrieved on 2007-04-20.

- ↑ "Volvo Construction Equipment (Europe}". Building the cities, towns, streets, highways and bridges in your neighborhood and in communities around the globe. Volvo (2007). Retrieved on 2007-04-20.

- ↑ Glossary: Princes Highway, Traralgon Bypass - Planning Assessment Report at The State of Victoria

- ↑ "ISAP 9th Conference Titles & Abstracts (#09044)". Effects of Frost Heave on the Longitudinal Profile of Asphalt Pavements in Cold Regions. International Society for Asphalt Pavements (August 2002). Retrieved on 2007-05-13.

- ↑ The Motorway Achievement: Frontiers of Knowledge and Practice. Thomas Telford. 2002. pp. 252. ISBN 0727731971. http://books.google.com/books?id=7Yqxyefv-VAC&pg=PA252&ots=Yvl1puH55J&dq=4th+power+of+axle+weight&sig=qNz9nc_S0HgJDblEONAZXcS605g.

- ↑ O'Flaherty, Coleman A. (2002). Highways: The Location, Design, Construction & Maintenance of Road Pavements. Elsevier. pp. 252. ISBN 0750650907. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ren4sWQ3jKkC&pg=PA252&ots=9b8s3lyHfg&dq=Pavements+are+designed+for+an+expected+service+life&sig=Wl0QDnn4_4vaXb-TQI8TiBarVAw.

- ↑ "Road Map to the Future". United States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration (July/August 2002). Retrieved on 2007-05-13.

- ↑ ISG Resources, Inc (December 2003). "Fly Ash Concrete Design for Chicago’s 100-Year Road Structure" (PDF). Case Study. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved on 2007-05-13.

- ↑ "Thin Surfacing - Effective Way of Improving Road Safety within Scarce Road Maintenance Budget" (PDF). Paper for presentation at the 2005 Annual Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada in Calgary, Alberta. Transportation Association of Canada (2005). Retrieved on 2007-05-14.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||