Theology

Theology is the study of a god or the gods from a religious perspective.[1] It has been commonly defined as reasoned discourse concerning the existence of one or more gods, or more generally about religion or spirituality. It can be contrasted with religious studies, which is the study of religion from a secular perspective. Theologians use various forms of analysis and argument (philosophical, ethnographic, historical) to help understand, explain, test, critique, defend or promote any of myriad religious topics. It might be undertaken to help the theologian:

- understand more truly his or her own religious tradition,[2]

- understand more truly another religious tradition,[3]

- make comparisons between religious traditions,[4]

- defend or justify a religious tradition,

- facilitate reform of a particular tradition,[5]

- assist in the propagation of a religious tradition,[6] or

- draw on the resources of a tradition to address some present situation or need,[7] or for a variety of other reasons.

The word 'theology' has classical Greek origins. The term was first used by Plato in The Republic (book ii, chap 18), and is compounded from two Greek words theos (god) and logos (rational utterance). It was gradually given new senses when it was taken up in both Greek and Latin forms by Christian authors. It is the subsequent history of the term in Christian contexts, particularly in the Latin West, that lies behind most contemporary usage, but the term can now be used to speak of reasoned discourse within and about a variety of different religious traditions.[8] Various aspects both of the process by which the discipline of ‘theology’ emerged in Christianity and the process by which the term was extended to other religions are highly controversial.

Contents |

History of the term

- See the main article on the History of theology, particularly for the history of Jewish, Christian and Islamic theology.

The word theology comes from late middle English (originally applying only to Christianity) from French théologie, from Latin theologia, from Greek: θεολογία, theologia, from θεός, theos or God + λόγος or logos, "words", "sayings," or "discourse" ( + suffix ια, ia, "state of", "property of", "place of"). The Greek word is literally translated as "to talk about God" from Θεός (Theos) which is God and logy which derives from logos, though this raises the question of the meaning of the word "God".[9] The meaning of the word "theologia"/"theology" shifted, however, as it was used (first in Greek and then in Latin) in European Christian thought in the Patristic period, the Middle Ages and Enlightenment, before being taken up more widely.

- The term θεολογια theologia is used in Classical Greek literature, with the meaning "discourse on the gods or cosmology".[10]

- Aristotle divided theoretical philosophy into mathematike, physike and theologike, with the latter corresponding roughly to metaphysics, which for Aristotle included discussion of the nature of the divine.[11]

- Drawing on Greek sources, the Latin writer Varro influentially distinguished three forms of such discourse: mythical (concerning the myths of the Greek gods), rational (philosophical analysis of the gods and of cosmology) and civil (concerning the rites and duties of public religious observance).[12]

- Christian writers, working within the Hellenistic mould, began to use the term to describe their studies. It appears once in some biblical manuscripts, in the heading to the book of Revelation: apokalypsis ioannoy toy theologoy, "the revelation of John the theologos". There, however, the word refers not to John the "theologian" in the modern English sense of the word but - using a slightly different sense of the root logos meaning not "rational discourse" but "word" or "message" - one who speaks the words of God, logoi toy theoy.[13]

- Other Christian writers used this term with several different ranges of meaning.

- Some Latin authors, such as Tertullian and Augustine followed Varro's threefold usage, described above.[14]

- In patristic Greek sources, theologia could refer narrowly to devout and inspired knowledge of, and teaching about, the essential nature of God.[15]

- In some medieval Greek and Latin sources, theologia (in the sense of "an account or record of the ways of God") could refer simply to the Bible.[16]

- In scholastic Latin sources, the term came to denote the rational study of the doctrines of the Christian religion, or (more precisely) the academic discipline which investigated the coherence and implications of the language and claims of the Bible and of the theological tradition (the latter often as represented in Peter Lombard's Sentences, a book of extracts from the Church Fathers).[17]

- It is the last of these senses (theology as the rational study of the teachings of a religion or of several religions) that lies behind most modern uses (though the second - theology as a discussion specifically of a religion's or several religions' teachings about God - is also found in some academic and ecclesiastical contexts; see the article on Theology Proper).

- 'Theology' can also now be used in a derived sense to mean 'a system of theoretical principles; an (impractical or rigid) ideology'.[18]

Religions other than Christianity

In academic theological circles, there is some debate as to whether theology is an activity peculiar to the Christian religion, such that the word 'theology' should be reserved for Christian theology, and other words used to name analogous discourses within other religious traditions.[19] It is seen by some to be a term only appropriate to the study of religions that worship a deity (a theos), and to presuppose belief in the ability to speak and reason about this deity (in logia) - and so to be less appropriate in religious contexts which are organized differently (religions without a deity, or which deny that such subjects can be studied logically). (Hierology has been proposed as an alternative, more generic term.)

Analogous discourses

- Some academic inquiries within Buddhism, dedicated to the rational investigation of a Buddhist understanding of the world, prefer the designation Buddhist philosophy to the term Buddhist theology, since Buddhism lacks the same conception of a theos. Jose Ignacio Cabezon, who argues that the use of 'theology' is appropriate, can only do so, he says, because 'I take theology not to be restricted to discourse on God…. I take "theology" not to be restricted to its etymological meaning. In that latter sense, Buddhism is of course atheological, rejecting as it does the notion of God.'[20]

- There is, within Hindu philosophy, a solid and ancient tradition of philosophical speculation on the nature of the universe, of God (termed Brahman in some schools of Hindu thought) and of the Atman (soul). The Sanskrit word for the various schools of Hindu philosophy is Darshana (meaning, view or viewpoint). Vaishnava theology has been a subject of study for many devotees, philosophers and scholars in India for centuries, has in recent decades also been taken on by a number of academic institutions in Europe, such as the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies and Bhaktivedanta College. See also: Krishnology

- Islamic theological discussion which parallels Christian theological discussion is named "Kalam"; the Islamic analogue of Christian theological discussion would more properly be the investigation and elaboration of Islamic law, or "Fiqh". 'Kalam ... does not hold the leading place in Muslim thought that theology does in Christianity. To find an equivalent for "theology" in the Christian sense it is necessary to have recourse to several disciplines, and to the usul al-fiqh as much as to kalam.' (L. Gardet)[21] A number of Muslim theologians such as Alkindus, Alfarabi, Avicenna (see Avicennism) and Averroes (see Averroism) have had a significant influence on the development of Christian theology.

- In Judaism the historical absence of political authority has meant that most theological reflection has happened within the context of the Jewish community and synagogue, rather than within specialised academic institutions. Nevertheless Jewish theology has been historically very active and highly significant for Christian and Islamic Theology. Once again, however, the Jewish analogue of Christian theological discussion would more properly be Rabbinical discussion of Jewish law and Jewish Biblical commentaries.

Within academia

Theology has a significantly problematic position within academia that is not shared by any other subject. Most universities founded before the modern era grew out of the church schools and monastic institutions of Western Europe during the High Middle Ages (e.g. University of Bologna, Paris University and Oxford University). They were founded to train young men to serve the church in Theology and Law (often Church or Canon law). At such universities, theological study was incomplete without Theological practice, including preaching, prayer and celebration of the Mass. Ancient Universities still maintain some of these links (e.g. having chapels and chaplains) and are more likely to teach Theology than other institutions.

During the High Middle Ages theology was therefore the ultimate subject at universities, being named "The Queen of the Sciences", and serving as the capstone to the Trivium and Quadrivium that young men were expected to study. This meant that the other subjects (including Philosophy) existed primarily to help with theological thought.

With the Enlightenment, universities began to change, teaching a wide range of subjects, especially in Germany, and from a Humanistic perspective. Theology was no longer the principal subject and Universities existed for many purposes, not only to train Clergy for established churches. Theology thus became unusual as the only subject to maintain a confessional basis in otherwise secular establishments. However, this did not lead to the abandonment of theological study.

Eventually, several prominent colleges and universities were started to train Christian ministers in the U.S. Harvard, Georgetown University, Boston College, Yale, Princeton, and Brown University all began in order to train preachers in Bible and theology. However, now some of these universities teach theology as a more academic than ministerial discipline.

With the rise of Christian education, renowned seminaries and Bible colleges have continued the original purpose of these universities. Chicago Theological Union, Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, Creighton University Omaha, University of Notre Dame in South Bend IN, University of San Francisco, Criswell College in Dallas, Southern Seminary in Louisville, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Wheaton College and Graduate School in Wheaton, Dallas Theological Seminary in Dallas, London School of Theology, as well as many others have influenced higher education in theology in philosophy to this day.

Theology is generally distinguished from other established academic disciplines that cover similar subject material (such as intellectual history or philosophy). Much of the debate concerning theology's place in the university or within a general higher education curriculum centers on whether theology's methods are appropriately theoretical and (broadly speaking) scientific or, on the other hand, whether theology requires a pre-commitment of faith by its practitioners.

While theology often interacts with and draws upon the following, it is generally differentiated from:

- Comparative religion/Religious studies

- Philosophy of religion

- History of religions

- Psychology of religion

- Sociology of religion

- Anthropology of religion

All of these normally involve studying the historical or contemporary practices or ideas of one or several religious traditions using intellectual tools and frameworks which are not themselves specifically tied to any religious tradition, but are (normally) understood to be neutral or secular.

The whole idea of reasoned discourse about God suggests the possibility of a common intellectual framework or set of tools for investigating, comparing and evaluating traditions. Still, most maintain that theology is a field of study presupposed by a particular worldview of faith.

Studies in different institutions

In Europe, the traditional places for the study of theology have been universities and seminaries. Typically the Protestant state churches have trained their clergy in universities while the Roman Catholic church has used seminaries as well as universities for both the clergy and the laity. However, the secularization of European states has closed down the theological faculties in many countries while the Catholic church has increased the academical level of its priests by founding a number of pontifical universities.

In some countries, some state-funded Universities have theology departments (sometimes, but not always, universities with a medieval or early-modern pedigree), which can have a variety of formal relationships to Christian churches, or to institutions within other religious traditions. These range from Departments of Theology which have only informal or ad-hoc links to religious institutions (see, for instance, several Theology departments in the UK) to countries like Finland and Sweden, which have state universities with faculties of theology training Lutheran priests as well as teachers and scholars of religion - although students from the latter faculties can also go on to typical graduate careers such as marketing, business or administration, even if this is frowned upon by some.

See also

|

|

Footnotes

- ↑ Brodd, Jefferey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ↑ See, e.g., Daniel L. Migliore, Faith Seeking Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology 2nd ed.(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004)

- ↑ See, e.g., Michael S. Kogan, 'Toward a Jewish Theology of Christianity' in The Journal of Ecumenical Studies 32.1 (Winter 1995), 89-106; available online at [1]

- ↑ See, e.g., David Burrell, Freedom and Creation in Three Traditions (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1994)

- ↑ See, e.g., John Shelby Spong, Why Christianity Must Change or Die (New York: Harper Collins, 2001)

- ↑ See, e.g., Duncan Dormor et al (eds), Anglicanism, the Answer to Modernity (London: Continuum, 2003)

- ↑ See, e.g., Timothy Gorringe, Crime, Changing Society and the Churches Series (London:SPCK, 2004)

- ↑ See, for example, Contemporary Jewish Theology: A Reader, ed Elliott Dorff and Louis Newman (Oxford: OUP, 1998), Ignaz Goldziher's Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law (Princeton University Press, 1981), Roger Jackson and John J. Makransky's Buddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars (London: Curzon, 2000), and Jose Pereira, Hindu Theology (New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 1991)

- ↑ According to [2], "divine" coms ultimately from an Indo-European word meaning “shining.”

- ↑ Lidell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon''.

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book Epsilon.

- ↑ As cited by Augustine, City of God, Book 6, ch.5.

- ↑ This title appears quite late in the manuscript tradition for the Book of Revelation: the two earliest citations provided in David Aune's Word Biblical Commentary 52: Revelation 1-5 (Dallas: Word Books, 1997) are both 11th century - Gregory 325/Hoskier 9 and Gregory 1006/Hoskier 215; the title was however in circulation by the 6th century - see Allen Brent ‘John as theologos: the imperial mysteries and the Apocalypse’, Journal for the Study of the New Testament 75 (1999), 87-102.

- ↑ See Augustine reference above, and Tertullian, Ad Nationes, Book 2, ch.1.

- ↑ Gregory of Nazianzus uses the word in this sense in his fourth-century Theological Orations; after his death, he was himself called 'the Theologian' at the Council of Chalcedon and thereafter in Eastern Orthodoxy - either because his Orations were seen as crucial examples of this kind of theology, or in the sense that he was (like the author of the Book of Revelation) seen as one who was an inspired preacher of the words of God. (It is unlikely to mean, as claimed in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers introduction to his Theological Orations, that he was a defender of the divinity of Christ the Word.) See John McGukin, Saint Gregory of Nazianzus: An Intellectual Biography (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2001), p.278.

- ↑

See e.g., Hugh of St. Victor, Commentariorum in Hierarchiam Coelestem, Expositio to Book 9: 'theologia, id est, divina Scriptura' (in Migne's Patrologia Latina vol.175, 1091C).

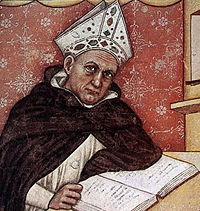

Albert the Great, patron saint of Roman Catholic Theologians

Albert the Great, patron saint of Roman Catholic Theologians - ↑ See the title of Peter Abelard's Theologia Christiana, and - perhaps most famously, of Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 1989 edition, 'Theology' sense 1(d), and 'Theological' sense A.3; the earliest reference given is from the 1959 Times Literary Supplement 5 June 329/4: 'The "theological" approach to Soviet Marxism...proves in the long run unsatisfactory.'

- ↑ See, for example, the initial reaction of Dharmachari Nagapriya in his review of Jackson and Makrasnky's Buddhist Theology (London: Curzon, 2000) in Western Buddhist Review 3

- ↑ Jose Ignacio Cabezon, 'Buddhist Theology in the Academy' in Roger Jackson and John J. Makransky's Buddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars (London: Routledge, 1999), pp.25-52.

- ↑ L. Gardet, 'Ilm al-kalam' in The Encyclopedia of Islam, ed. P.J. Bearman et al (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 1999).

External links

- Pictures of Seminary in Namur (Belgium) - Features by Jean-Michel Clajot, Belgian photographer

- Conservative Theological Research

- The Theologian: the internet journal for integrated theology

- Christian Classics Library

- University course: Entheogens — Sacramentals or Sacrilege?

- Intuitive Knowledge of God in Medieval Jewish Theology by Jose Faur, contrasting the intuitive theology of the medieval Rabbanites with the hyper-rationalism of the Karaites

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||