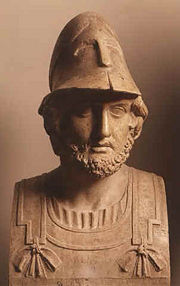

Themistocles

Themistocles (Greek: Θεμιστοκλῆς; c. 524–459 BC[1]) was an Athenian soldier and statesman. As archon in 493 BC, he convinced the Athenians that a powerful fleet was needed to protect them against the Persians. During the second Persian invasion under Xerxes I, he commanded the Athenian squadron and through his strategy the Greeks won the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. After the war, he persuaded the Athenians to rebuild the walls of the city on a vastly larger scale than had existed before. This aroused uneasiness in Sparta. So the Spartan faction in Athens tried to undermine him and in 470 BC he was ostracised. He moved to Argos, but the Spartans forced his expulsion from there in 467 BC. He eventually travelled to Persia where the king Artaxerxes I made him governor of Magnesia where he spent the rest of his life. He was a man of grand plans whose patriotism later became confused with his own advancement. He was convinced that only he could realise the dream of a great Athenian empire.

Contents |

Biography

Themistocles was the son of Neocles, an Athenian of no distinction and moderate means, his mother being a Carian or a Thracian, Abrotonum by some accounts.[2] Little is known of his early years, but many authors resort to the myth that he was unruly as a child and was consequently disowned by his father (e.g. Libanius Declamations 9 and 10; Aelian[which?]; Cornelius Nepos "Themistocles"). He may have been strategos of his tribe at Marathon and it is said that he was jealous of the victories of Miltiades, repeating to himself, "Miltiades' trophy does not let me sleep" (in Greek: Οὐκ ἐᾷ με καθεύδειν τὸ τοῦ Μιλτιάδου τρόπαιον).

Thucydides, a well-respected historian who was born around the time of Themistocles’ death, described him in the following terms:

| “ | Themistocles was a man who most clearly presents the phenomenon of natural genius... to a quite extraordinary and exceptional degree by sheer personal intelligence, without either previous study or special briefing, he showed both the best grasp of an emergency situation at the shortest notice, and the most far-reaching appreciation of probable future developments. | ” |

Plutarch, writing five centuries later in a very different world, is more disparaging. He uses Themistocles as an example of someone who is power-hungry and willing to use any means to gain both personal and national prestige.

The death of Miltiades, the hero of Marathon, left a political void filled by Themistocles and Aristides "the Just", with whom he had previously competed over the love of a boy. As Plutarch recounts, "... they were rivals for the affection of the beautiful Stesilaus of Ceos, and were passionate beyond all moderation."[3]

Themistocles prevailed in 483 BC–482 BC by arranging the ostracism of Aristides. Themistocles advocated a policy of naval expansion while Aristides represented the interests of the "hoplite" or traditional land-based military establishment. Athens' traditional enemy, Aegina, had a powerful navy while the danger of a renewed Persian invasion was well known. The Persians had recently subjugated the Ionian Greeks who were known for developing a new three level warship known as the "Trireme" which was destined to change naval warfare for years to come. Themistocles successfully persuaded the Athenian Assembly to build an additional 100 or 200 Triremes and to continue his work of fortifying the harbours of Piraeus largely facilitated by a fortuitous newly-discovered rich vein of silver at Laureion.

Themistocles may have been archon in 483 BC–482 BC at the time when this naval programme began. Dionysius of Halicarnassus places his archonship in 493-92, which may be more likely: in 487 the office lost much of its importance owing to the substitution of the lot for election: the chance that the lot would at the particular crisis of 483 fall on Themistocles was remote. In any case, at the year prior to the invasion of Xerxes Themistocles was the most influential politician in Athens, if not in Greece. Though the Greek fleet was nominally under the control of the Spartan Eurybiades, Themistocles caused the Greeks to fight the indecisive Battle of Artemisium, and more, it was he who brought about the Battle of Salamis, by his threat that he would lead the Athenian army to found a new home in the West, and by his seemingly treacherous message to Xerxes, whose fleet was lured into the channel between Salamis and the mainland and crushed.

This left the Athenians free to restore their ruined city. Sparta, on the ground that it was dangerous to Greece that there should be any citadel north of the Isthmus of Corinth which an invader might hold, urged against this, but Themistocles forstalled Spartan action by means of a visit to Sparta that allowed diplomatic delays and subterfuges and enabled the work to be carried sufficiently near to completion to make the walls defensible. He also carried out his original plan of making Piraeus a real harbour and fortress for Athens. Athens thus became the finest trade centre in Greece, and this, along with Themistocles' remission of the alien's tax, induced many foreign business men to settle in Athens.

After the crisis of the Persian invasion Themistocles and Aristides appear to have made up their differences. But Themistocles soon began to lose the confidence of the people, partly due to his arrogance (it is said that he built near his own house a sanctuary to Artemis Aristoboulë ["of good counsel"]) and partly due to his alleged readiness to take bribes. Diodorus and Plutarch both refer to some accusation levelled against him, and at some point between 476 BC and 471 BC he was ostracised. He retired to Argos, but the Spartans further accused him of treasonable intrigues with Persia, and he fled to Corcyra, thence to Admetus, king of Molossia, and finally to Asia Minor. He was proclaimed a traitor at Athens and his property was confiscated, though his friends saved him some portion of it.

Eventually, Artaxerxes I, successor of Xerxes I, offered Themistocles asylum. He was well received by the Persians and was made governor of Magnesia on the Maeander River in Asia Minor (modern Turkey). The revenues (50 talents) of this town were assigned to him for bread, those of Myus for condiments, and those of Lampsacus for wine. His death at Magnesia, at the age of sixty-five, was due to illness according to Thucydides, although Thucydides also tells us of a rumor that Themistocles, finding that he could not keep the promises that he had made to Xerxes, may have taken poison (book I, 138). It was said that his bones were secretly transferred to Attica. He was worshiped by the Magnesians as a god, as depicted on a coin on which he is shown with a patera in his hand and a slain bull at his feet (hence perhaps the legend that he died from drinking bull’s blood).

Though many Greeks considered that his end was discreditable there is no doubt that his services to Athens and to Greece were great. He created the Athenian fleet and with it the possibility of the Delian League, which became the Athenian empire, and there are indications (e.g. his plan of expansion in the west) that the later imperialist ideal originated with him.

In popular culture

- In the movie The 300 Spartans (1962), Themistocles is portrayed by the actor Ralph Richardson

- In the film Lawrence of Arabia (1962) T. E. Lawrence, played by actor Peter O'Toole, quotes Themistocles saying, "I cannot fiddle, but I can make a great state from a little city."

- The historical novel Farewell Great King by Jill Paton Walsh follows the life, unto death, of Themistocles. It is based primarily upon the Life of Themistocles and Life of Aristides from Plutarch.

References and notes

- ↑ Hornblower and Spawforth (1998) s.v. Themistocles. Secondary sources vary on the dates of birth and death. Other dates often given are 525/523 - 460 BC.

- ↑ Smith, William (1867), "Abrotonum", in Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1, Boston, MA, pp. 3

- ↑ Plutarch, The Lives, "Themistocles"

Bibliography

- JACT, The World of Athens

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Hornblower, Simon and Spawforth, Antony (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

External links

- Livius.org, Themistocles by Jona Lendering

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||