Theatre of Pompey

|

Theatre of Pompey |

|

|---|---|

Theatre of Pompey |

|

| Location | Regione IX Circus Flaminius |

| Built in | 55 BC |

| Built by/for | Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus |

| Type of structure | Roman theatre (structure) |

|

Theatre of Pompey |

|

The Theatre of Pompey (Latin: Theatrum Pompeium, Italian: Teatro di Pompeo) was an ancient structure built during the Roman Republic era begun in 61 BC. It was dedicated early in 55 BC before the structure was fully completed.[1] The theatre was one of the first permanent (non-wooden) theatres in Rome and was considered the world's largest theatre for centuries. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus financed his theatre to gain political popularity during his second consulship.[2] It was not only a theatre but had mutliple uses. The building had the largest "Crypta" of all of the Roman theatres which contained statues of great artists and actors. Long arcades exhibiting collections of paintings and sculpture as well as a large space suitable for holding public gatherings and meetings made the facility an attraction to Romans for many reasons.

The highest point of the Structure was the Temple to Venus Victrix, Pompey's personal deity (compared to Julius Caesar's worship of Venus Genetrix as his personal deity). Some modern scholars believe this was not mere piety, but essential in order that the structure should not be seen as a self-promoting extravagance as well as to overcome a moratorium on permanent theatre buildings.[3]

The remains of the east side of the Portico attached to the theatre and three of four temples from an earlier period often associated with the theatre can be seen on the Largo di Torre Argentina. The fourth temple remains largely covered by the modern streets of Rome. This archaeological site was excavated by order of Mussolini in the 1920s and 30s. The scarce remains of the theatre itself can be found off the Via di Grotta Pinta underground; vaults from the original theatre can be found in the cellar rooms of restaurants off this street, as well as in the walls of the hotel Albergo Sole al Biscione. This is due in large part to sedimant build up over the centuries before the structure began to be disassembled. The foundations of the theatre as well as part of the first level and the cavea remain, however have been built over and added on to a point that what is left is part of the modern structures.

During the theatre's long history, which stretches from 55 BC to approximately 1455 AD, the structure endured several restorations due mainly to fire. Eventually falling into disrepair, it became a quarry for the stone that had made up the large theatre.

Contents |

Architecture

The characteristics of Roman theatres are similar to those of the earlier Greek theatres, on which they are based. Much of the architectural influence on the Romans came from the Greeks, and theatre structural design was no different from other buildings in that respect. However, Roman theatres have specific differences, such as being built upon their own foundations instead of earthen works or a hillside and being completely enclosed on all sides. Roman theatres derive their basic design from the Theatre of Pompey, the first permanent Roman theatre.

The Romans built concrete foundations from the ground up, creating vaulted corridors underneath the seating as access to each section of the auditorium. In doing this a circular exterior was created using the Roman innovation of the arch. This innovation allowed for a much larger edifice with greater structural integrity. This also made the auditorium a structure in itself and not just simple earthen works. This is not to say that all Roman theatres were built in this manner, only that Romans could build their theatres in even the flattest lands.

The stage section of the theatre is attached directly to the auditorium making both a singular structure enclosed all around, where Greek theatres separate the two. This made for both better acoustics and limited the entrance to the building allowing tickets to be collected at central access areas (clay pottery tickets being another Roman innovation).

This architecture was copied for nearly all future theatres and amphitheatres within the ancient city of Rome and throughout the empire. Notable structures that used this similar style are the Colosseum and the Theatre of Marcellus, both of which have ruins that still exist in Rome today.

Complex

The entire theatre structure was large enough to include multiple uses. Even when performances were not scheduled the theatre was busy with activity with varied purposes. The Temple of Venus as its crown on one side and the more ancient sacred area on the other made the site of religious importance as well. Today nearly all archaeological work is focused at the remains of the theatre section. However, the theatre included a completely enclosed private garden with museum collections and meeting spaces that expanded past the auditorium, orchestra and stage.

Temples

In order to build the theatre as a permanent stone structure a number of things were done, including building outside the city walls. By dedicating the theatre to Venus Victrix and building the temple central within the cavea, Pompey makes the structure a large shrine to his personal deity. He also incorporates four Republican temples from an earlier period in a section called the "Sacred Area" in what is today known as Largo di Torre Argentina. The entire complex is built directly off the older section which directs the structure's layout. In this manner the structure had a day to day religious context and incorporates an older series of temples into the newer structure to have real purpose The theatre was made in a total of seven years

Temple A was built in the 3rd century BC, and is probably the Temple of Juturna built by Gaius Lutatius Catulus after his victory against the Carthaginians in 241 BC.[4] It was later rebuilt into a church, whose apse is still present.

Temple B, a circular temple with six columns remaining, was built by Quintus Lutatius Catulus in 101 BC to celebrate his victory over Cimbri; it was Aedes Fortunae Huiusce Diei, a temple devoted to the "Luck of the Current Day". The colossal statue found during excavations and now kept in the Capitoline Museums was the statue of the goddess herself. Only the head, the arms, and the legs were of marble: the other parts, covered by the dress, were of bronze.

Temple C is the most ancient of the three, dating back to 4th or 3rd century BC, and was probably devoted to Feronia the ancient Italic goddess of fertility. After the fire of 80 AD, this temple was restored, and the white and black mosaic of the inner temple cell dates back to this restoration.

Temple D is the largest of the four; it dates back to 2nd century BC with Late Republican restorations, and was devoted to Lares Permarini, but only a small part of it has been excavated (a street covers the most of it).

The theatre had a large temple built at the top center of the seating semicircle in front of the stage. It was the highest part of the entire complex. It was sanctified as a temple to Pompey's personal god Venus Victrix.

Garden and museums

The theatre Complex itself was designed for all the many artistic accomplishments of the time. The theatre also played host to a fully enclosed garden with fountains and sculpture surrounded by long columned porticoes located directly behind the Stage. Inside the surrounding arcades of the garden area were exhibits of art. Large collections of paintings along with great Sculptures adorned the entire complex. Many pieces survive in museums throughout Rome today.

Curia, assassination of Caesar

The location of the theatre is of historic significance in large part due to a single murder that took place in the complex, located in the large crypta behind the stage. The large garden area had a meeting room or curia in the far end near the sacred area.

On the Ides of March (March 15; see Roman calendar) of 44 BC, a group of senators called Caesar to the forum for the purpose of reading a petition, written by the senators, asking him to hand power back to the Senate. However, the petition was a fake.[5] Mark Antony, having vaguely learned of the plot the night before from a terrified Liberator named Servilius Casca, and fearing the worst, went to head Caesar off at the steps of the forum. However, the group of senators intercepted Caesar just as he was passing the Theatre of Pompey, located in the Campus Martius, and directed him to a room adjoining the east portico.[6]

As Caesar began to read the false petition, Tillius Cimber, who had handed him the petition, pulled down Caesar's tunic. While Caesar was crying to Cimber "But that is violence!" ("Ista quidem vis est!"), the aforementioned Casca produced his dagger and made a glancing thrust at the dictator's neck. Caesar turned around quickly and caught Casca by the arm, saying in Latin "Casca, you villain, what are you doing?"[7] Casca, frightened, shouted "Help, brother" in Greek ("ἀδελφέ, βοήθει!", "adelphe, boethei!"). Within moments, the entire group, including Brutus, was striking out at the dictator. Caesar attempted to get away, but, blinded by blood, he tripped and fell; the men continued stabbing him as he lay defenseless on the lower steps of the portico. According to Eutropius, around sixty or more men participated in the assassination. He was stabbed 23 times.[8] According to Suetonius, a physician later established that only one wound, the second one to his chest, had been lethal.[9]

This single violent act was one of the most memorable moments in Roman history and set the stage for the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

While history records this location as the place Caesar fell, it is often confused with other meeting spaces by the senate. The first senate building was The Curia Hostilia built in the 7th century BC by Tullus Hostilius and repaired in 80 BC by Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The Curia Julia was begun by Caesar before his death on a different site after the first curia was destroyed by fire.

Today most of the location of the curia at the Theatre of Pompey is covered by roadway; however, a portion of its wall near the Sacred Area was excavated by Mussolini.

The site today

Owing in large part to Christian influence and the church's view of theatre, the site fell into disrepair and much was dismantled and carted off to build other structures throughout the city. Part of the building was made into a fortress during medieval times. Much of what is left today is located in cellars of the surrounding neighbourhood of hotels, homes and restaurants.

Pieces from the structure can be located throughout the city of Rome, including sculpture and other archaeological finds. The largest intact sections of the theatre are found in the Palazzo della Cancelleria, which used much of the bone colored travertine for its exterior from the theatre. The large red and grey columns used in its courtyard are from the porticoes of the theatres upper covered seating, however they were originally taken from the theatre to build the old Basilica of S. Lorenzo.[10]

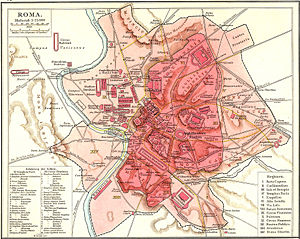

Located in the Campus Martius, a dense neighbourhood of later buildings has grown in and around the area. The entire site is now covered by later buildings and streets. However, the shape of the theatre is still distinguishable in an aerial view. In some locations, buildings were built directly on top of the theatre's original foundations from the curved seating. This has resulted in several curved buildings and streets.

Limited archaeological work on the site has taken place over the years. Many early excavations were not documented; however, a few have done some work to estimate the area and map out plans based on the broken marble map that once adorned the Temple of Peace called the Forma Urbis Romae.

Luigi Canina (1795-1856) was the first to undertake serious research on the Theatre. It was Canina who discovered the representation of the theatre on the Forma Urbis as well as the first study of the existing remains. His are the first re-construction drawings to be attempted. It was on these drawings that Martin Blazeby based his recent 3D images.[11]

Newer, more recent studies have been carried out just in the past few years. Because of the modern buildings and streets as well as other factors like plumbing and electrical sources, digging for theatre remains has always been difficult. Recent projects have developed more updated plans of the theatre and its location has been more accurately identified.

Archaeology

The site of the theatre has been heavily plundered of nearly all of it stones and columns; however, there still exist basement and sub-basement levels located beneath what was the spectators' seating of the ancient theatre which have all endured centuries of subsequent construction. Roman ruins were built directly onto by subsequent owners of land, using the original Roman structures as foundations, so making their work stronger and cheaper than building new. The Theatre of Marcellus has several apartments still in use from the small fortress built on top of its ruins.

Parts of the structure that had been found in the area during construction work from the Renaissance to the mid-18th century inspired interest in a serious investigation of the theatre.

Luigi Canina began the first study of the Forma Urbis and attempted a reconstruction from known ruins. He recorded descriptions of the building in the early 19th century; these illustrations were then later modified by Victoire Baltard, a French architect, in 1837. Baltard also made two excavations in the surrounding area, uncovering remains of the exterior and scaenae frons.

In 1865, while foundations were being dug for a new building for Pietro Righetti, who owned Palazzo Pio at the time, parts of the Temple of Venus Victrix were discovered.

Not until 1997 was any serious archaeological study made of the area. Directed by Richard Beckham and co-directed by James Packer, a team based at the University of Warwick began a comprehensive survey of the existing state of the remains of the Theatre. In 2002, architect Silenzi and professor Packer began excavation at Palazzo Pio.

Existing Roman Theatres of this style

Although the Theatre of Pompey no longer exists as a structure today, many similar buildings do survive throughout Europe and Africa. They help us to understand what the Theatre of Pompey was to the ancients, and how this single theatre had influences all over the empire. The best examples of this type of theatre can be found outside of Italy. One such theatre is in the town of Orange (in the Rhone Valley, France) known as the Théâtre antique d'Orange. The exterior of this theatre remains very well preserved. Unfortunately it was built upon a hillside and does not have the curved front. Instead the theatre is reversed with the curved seating section in the rear. Others theatres exist in Spain and Africa with remains that demonstrate the multiple arched curve of the exterior as well as better preserved stage areas.

While there is a theatre in the remains of the city of Pompeii,[12] which was destroyed by a volcanic eruption, the Theatre of Pompey in Rome was much larger in scale. The theatre in Pompeii does however have a similar back garden area enclosed like the one that was in Rome. The theatre in Pompeii is still in use today, as are many remaining Roman theatres.

References

- ↑ Boatwright et al., The Romans, From Village to Empire, p. 227 ISBN 9780195118766

- ↑ History of the Theatre - Antiquity

- ↑ Theatrum Pompeii in Platner & Ashby

- ↑ This identification is preferred over the one as Temple of Iuno Curritis, because Ovidius (Fasti I) says: "Te quoque lux eadem Turni soror aede recepit/Hic, ubi Virginea Campus obitur aqua", thus posing the temple of Juturna near the Aqua Virgo, which ended at the Baths of Agrippa.

- ↑ "Petition effectiveness: improving citizens’ direct access to parliament". Parliament of Western Australia. Retrieved on 2008-08-28.

- ↑ "Theatrum Pompei". Oxford University Press. Retrieved on 2008-08-28.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Caesar, ch. 66: "ὁ μεν πληγείς, Ῥωμαιστί· 'Μιαρώτατε Κάσκα, τί ποιεῖς;'"

- ↑ Woolf Greg (2006), Et Tu Brute? - The Murder of Caesar and Political Assassination, 199 pages - ISBN 1-8619-7741-7

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius, c. 82.

- ↑ Middleton, John Henry (1892). Remains of Ancient Rome, volume 2. Adamant Media Corporation. pp. 69. ISBN 140217473X.

- ↑ Site Documentation

- ↑ "Theatre of Pompeii". AncientWorlds LLC. Retrieved on 2008-13-05.

See also

- Opera Publica

External links

- The Pompey Project

- The Theatre of Pompey

- Theatrum Pompei at LacusCurtius (article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome)

- The Temple above Pompey's Theatre (CJ 39:360‑366)

- Pompey’s Politics and the Presentation of His Theatre-Temple Complex, 61–52 BCE

- theaterofpompey.com

- Roma Online Guide