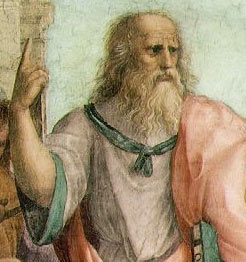

The Republic (Plato)

|

| Part of the series on: The Dialogues of Plato |

| Early dialogues: |

| Apology – Charmides – Crito |

| Euthyphro – First Alcibiades |

| Hippias Major – Hippias Minor |

| Ion – Laches – Lysis |

| Transitional (middle) dialogues: |

| Cratylus – Euthydemus – Gorgias |

| Menexenus – Meno – Phaedo |

| Protagoras – Symposium |

| Later middle dialogues: |

| Republic – Phaedrus |

| Parmenides – Theaetetus |

| Late dialogues: |

| Timaeus – Critias |

| Sophist – Statesman |

| Philebus – Laws |

| Of doubtful authenticity: |

| Clitophon – Epinomis |

| Epistles – Hipparchus |

| Minos – Rival Lovers |

| Second Alcibiades – Theages |

The Republic (Greek: Πολιτεία / Politeía, meaning "political system;" Latin: Res Publica, meaning "public business" or literally "public thing") is a Socratic dialogue by Plato, written in approximately 380 BC.[1] It is one of the most influential works of philosophy and political theory, and arguably Plato's best known work. In it, Socrates and various other Athenians and foreigners discuss the meaning of justice and whether the just man is happier than the unjust man by constructing an imaginary city ruled by philosopher-kings. The dialogue also discusses the nature of the philosopher, Plato's Theory of Forms, the conflict between philosophy and poetry, and the immortality of the soul. [2]

Contents |

Book title

The title of the Republic in Greek, politeia, literally means the order or character of a political community, i.e., its constitution or regime type. For various reasons, this was rendered in Latin as res publica, the "public business" or the "commonwealth." Greek works used to be referred to by their Latin or Latinized titles, and so Plato's dialogue came to be known in English as the Republic. It is not, however, primarily a work on republicanism in the modern sense of the term. Regardless, the title of the Republic is still used on account of that tradition.

Setting and dramatis personae

The scene of the dialogue is the house of Polemarchus at Piraeus, a city-port connected to Athens by the Long Walls. Socrates was not known to venture outside Athens regularly. The whole dialogue is narrated by Socrates the day after it actually took place - possibly to Timaeus, Hermocrates, Critias, and another unnamed person, but this interpretation is somewhat uncertain.[3]

Characters

- Socrates the main protagonist

- Cephalus, an elderly arms manufacturer;[4] appears only in the introduction

- Thrasymachus, a Chalcedonian sophist

- Glaucon, son of Ariston

- Adeimantus, son of Ariston

- Polemarchus, son of Cephalus

- Cleitophon, son of Aristonymus

- Charmantides, a Paeanian (silent)

- Lysias, son of Cephalus (silent)

- Euthydemus, son of Cephalus (silent)

- Niceratus, son of Nicias (silent)

In addition to the named characters, there are several members of the Piraean religious procession present.

Structure

Three interpretations, or summaries, of Plato's Republic follow. They are not, by any measure, an exhaustive representation, but represent accepted contemporary English language views on the work.

Bertrand Russell

In his History of Western Philosophy (1945), Bertrand Russell sees three parts in Plato's Republic:[5]

- Book I-V: the Utopia portion, portraying the ideal community, starting from an attempt to define justice;

- Book VI-VII: since philosophers are seen as the ideal rulers of such community, this part of the text concentrates on defining precisely what a philosopher is;

- Book VIII-X: discusses several practical forms of government, their pros and cons.

The core of the second part is discussed in Plato's Allegory of the Cave, and articles related to Plato's theory of (ideal) forms. The third part, concentrating also on education, is also strongly related to Plato's dialogue The Laws.

Cornford, Hildebrandt and Voegelin subdivisions

Francis Cornford, Kurt Hildebrandt and Eric Voegelin contributed to an establishment of subdivisions marked by special formulae in Greek:

- Prologue

- I.1. 327a—328b. Descent to the Piraeus

- I.2—I.5. 328b—331d. Cephalus. Justice of the Older Generation

- I.6—1.9. 331e—336a. Polemarchus. Justice of the Middle Generation

- I.10—1.24. 336b—354c. Thrasymachus. Justice of the Sophist

- Introduction

- II.1—II.10. 357a—369b. The Question: Is Justice Better than Injustice?

- Part I: Genesis and Order of the Polis

- II.11—II.16. 369b—376e. Genesis of the Polis

- II.1—III.18. 376e—412b. Education of the Guardians

- III.19—IV.5. 412b—427c. Constitution of the Polis

- IV.6—IV.I9. 427c—445e. Justice in the Polis

- Part II: Embodiment of the Idea

- V.1—V.16. 449a—471c. Somatic Unit of Polis and Hellenes

- V.17—VI.14. 471c—502c. Rule of the Philosophers

- VI.19—VII.5. 502c—521c. The Idea of the Agathon

- VII.6—VII.18. 521c—541b. Education of the Philosophers

- Part III: Decline of the Polis

- VIII.1—VIII.5. 543a—550c. Timocracy

- VIII.6—VIII.9. 550c—555b. Oligarchy

- VIII.10—VIII.13. 555b—562a. Democracy

- VIII.I4—IX-3. 562a—576b. Tyranny

- Conclusion

- IX.4—IX.13. 576b—592b Answer: Justice is Better than Injustice

- Epilogue

- X.1—X.8. 595a—608b. Rejection of Mimetic Art

- X.9—X.11. 608c—612a. Immortality of the Soul

- X.12. 612a—613e. Rewards of Justice in Life

- X.13—X.16. 613e—631d. Judgment of the Dead

The paradigm of the city - the idea of the Good, of the Agathon - has for Plato manifold historical embodiments. The embodiment must be undertaken by those who have seen the Agathon and are ordered through the vision. Hence, in the centre piece of the Republic, Part II, 2-3, Plato deals with the rule of the philosopher and the vision of the Agathon in the famous allegory of the cave, with which Plato clarifies his theory of forms.

That center piece is preceded and followed by the discussion of the means that will secure a well-ordered polis. Part II, 1 deals with marriage, the community of people and goods for the guardians, and the restraints on warfare among the Hellenes. It has been described as a communistic utopia, a word that is not extant in classical Greek. Part II, 4 deals with the philosophical education of the rulers who will preserve the order.

The central Part II, the Embodiment of the Idea, is preceded by the building of economic and social of order for a polis in Part I; and is followed by an analysis in Part III, of the decline through which the right order will have to pass. The three parts form the main body of the dialogue, with their discussion of paradigm , its embodiment, its genesis, and its decline.

That main body is framed by an Introduction and a Conclusion. The discussion of right order was occasioned by a question whether justice is better than injustice, or whether unjust man will not fare better than the just man. The introductory question is balanced by the concluding answer that justice is preferable to injustice.

The main body of the dialogue, together with its Introduction and Conclusion, finally, is framed by the Prologue of Book I and the Epilogue of Book X. The prologue is a short dialogue in itself and it portrays the common opinions doxai about justice. The Epilogue is not grounded in reason but in faith. It describes the new arts and the immortality of the soul.

Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss saw a four-part structure of the dialogue: he looked at the entire dialogue as a drama played out between particular characters, each with particular points of view and levels of comprehension:

- Book I: Socrates is compelled by force to Cephalus's home. Three definitions of justice are presented, and all three are found lacking.

- Books II-V: Socrates is challenged by Glaucon and Adeimantus to prove why a perfectly just person, who is seen by the entire world as unjust, would be happier than the perfectly unjust person, who hides his injustice from view and is seen by the entire world as just. This stark challenge is the engine and drive of the dialogue; it is only with this 'charge' that we begin to witness how Socrates actually conducted himself with the young men of Athens he was convicted of corrupting. Because a definition of justice is assumed by Glaucon and Adeimantus, Socrates makes a detour; he forces the group to try to uncover justice, and then to answer the question posed to him about the intrinsic value of the just life.

- Books V-VI: The 'Just City in Speech' is now built from the earlier books, and three waves or critiques of the city are encountered. According to Leo Strauss and his student Allan Bloom they are: communism, communism of wives and children, and the rule of philosophers. The 'Just City in Speech’ stands or falls by these complications.

- Books VII-X: Socrates has 'escaped' his capturers, for he has convinced them, at least for the moment, that the just man is the happy man. He then spends much time reinforcing their prejudices. He displays a rationale for political decay, and he ends the dialogue recounting a myth, The Myth of Er, or everyman, which acts as a consolation for non-philosophers who fear death.

Topics

Definition of justice

Justice ultimately becomes, in Book IV, the action of doing what one ought to do, or of doing what one does best, according to one's class within society. A just society is one in which the organization of the polis, or city-state, mirrors the organization of the tripartite soul. Thus the three classes in the polis each correspond to a part of the soul, as the guardians correspond to the rational part of the soul, the auxiliaries correspond to the spirited part of the soul, and the working-class corresponds to the desiring part of the soul. The three classes, according to their engagement in their particular corresponding part of the soul, thus each have a virtue most appropriate to it. The guardians must be wise, the auxiliaries must be courageous , and all three (including the working-class) must exhibit moderation.

In the first book, two definitions of justice are proposed but deemed inadequate. Returning debts owed, and helping friends while harming enemies are commonsense definitions of justice that, Socrates shows, are inadequate in exceptional situations, and thus lack rigidity demanded of a definition. Yet he does not completely reject them for each expresses a common sense notion of justice which Socrates will incorporate into his discussion of the just regime in books II through V.

At the end of Book I, Socrates agrees with Polemarchus that justice includes helping friends, but says the just man would never do harm to anybody. Thrasymachus believes that Socrates has done the men present an injustice by saying this and attacks his character and reputation in front of the group, partly because he suspects that Socrates himself does not even believe harming enemies is unjust. Thrasymachus gives his understanding of justice as "what is good for the stronger", meaning those in power over the city. Socrates finds this definition unclear and begins to question Thrasymachus. In Thrasymachus’ view, the rulers are the source of justice in every city, and their laws are just by his definition since, presumably, they enact those laws to benefit themselves. Socrates then asks whether the ruler who makes a mistake by making a law that lessens their well-being, is still a ruler according to that definition. Thrasymachus agrees that no true ruler would make such an error. This agreement allows Socrates to undermine Thrasymachus' strict definition of justice by comparing rulers to people of various professions. Thrasymachus consents to Socrates' assertion that an artist is someone who does his job well, and is a knower of some art, which allows him to complete the job well. In so doing Socrates gets Thrasymachus to admit that rulers who enact a law that does not benefit them firstly, are in the precise sense not rulers. Thrasymachus gives up, and is silent from then on. Socrates has trapped Thrasymachus into admitting the strong man who makes a mistake is not the strong man in the precise sense, and that some type of knowledge is required to rule perfectly. However, it is far from a satisfactory definition of justice.

At the beginning of Book II, Plato's two brothers challenge Socrates to define justice in the man, and unlike the rather short and simple definitions offered in Book I, their views of justice are presented in two independent speeches. Glaucon's speech reprises Thrasymachus' idea of justice; it starts with the legend of Gyges who discovered a ring that gave him the power to become invisible.[6] Glaucon uses this story to argue that no man would be just if he had the opportunity of doing injustice with impunity. With the power to become invisible, Gyges is able to enter the royal court unobserved, seduce the queen, murder the king, and take over the kingdom. Glaucon argues that the just as well as the unjust man would do the same if they had the power to get away with injustice exempt from punishment. The only reason that men are just and praise justice is out of fear of being punished for injustice. The law is a product of compromise between individuals who agree not to do injustice to others if others will not do injustice to them. Glaucon says that if people had the power to do injustice without fear of punishment, they would not enter into such an agreement. Glaucon uses this argument to challenge Socrates to defend the position that the just life is better than the unjust life.

Glaucon's speech seduces Socrates for it is in itself contradictory. Glaucon has openly, passionately and forcibly argued for the superiority of the unjust life, something truly unjust men would never do in public. Socrates says that there is no better topic to debate. In response to the two views of injustice and justice presented by Glaucon and Adeimantus, he claims incompetence, but feels it would be impious to leave justice in such doubt. Thus The Republic sets out to define justice. Given the difficulty of this task as proven in Book I, Socrates in Book II leads his interlocutors into a discussion of justice in the city, which Socrates suggests may help them see justice in the person, but on a larger scale.[7]

For over two and a half millennia, scholars have differed on the aptness of the city—soul analogy Socrates uses to find justice in Books II through V. The Republic is a dramatic dialogue, not a treatise. Socrates' definition of justice is never unconditionally stated, only versions of justice within each city are "found" and evaluated in Books II through Book V. Socrates constantly refers the definition of justice back to the conditions of the city for which it is created. He builds a series of myths, or noble lies, to make the cities appear just, and these conditions moderate life within the communities. The "earth born" myth makes all men believe that they are born from the earth and have predestined natures within their veins. Accordingly, Socrates defines justice as "working at that which he is naturally best suited," and "to do one's own business and not to be a busybody" (433a-433b) and goes on to say that justice sustains and perfects the other three cardinal virtues: Temperance, Wisdom, and Courage, and that justice is the cause and condition of their existence. Socrates does not include justice as a virtue within the city, suggesting that justice does not exist within the human soul either, rather it is result of a "well ordered" soul. A result of this conception of justice separates people into three types; that of the soldier, that of the producer, and that of a ruler. If a ruler can create just laws, and if the warriors can carry out the orders of the rulers, and if the producers can obey this authority, then a society will be just.

The city is challenged by Adeimantus and Glaucon throughout its development, Adeimantus cannot find happiness in the city, and Glaucon cannot find honour and glory. Ultimately Socrates constructs a city in which there is no private property, no private wife and children, and no philosophy for the lower castes. All is sacrificed to the common good and doing what is best fitting to your nature; however, is the city itself to nature? In Book V Socrates addresses this issue, making some assertions about the equality of the sexes (454d). Yet the issue shifts in Book VI to whether this city is possible, not whether it is a just city. The rule of philosopher-kings appear as the issue of possibility is raised. Socrates never positively states what justice is in the human soul, it appears he has created a city where justice is lost, not even needed, since the perfect ordering of the community satisfies the needs of justice in human races' less well ordered cities.

In terms of why it is best to be just rather than unjust for the individual, Plato prepares an answer in Book IX consisting of three main arguments. Plato says that a tyrant's nature will leave him with "horrid pains and pangs" and that the typical tyrant engages in a lifestyle that will be physically and mentally exacting on such a ruler. Such a disposition is in contrast to the truth-loving philosopher king, and a tyrant "never tastes of true freedom or friendship." The second argument proposes that of all the different types of people, only the Philosopher is able to judge which type of ruler is best since only he can see the Form of the Good. Thirdly, Plato argues, "Pleasures which are approved of by the lover of wisdom and reason are the truest." In sum, Plato argues that philosophical pleasure is the only true pleasure since other pleasures experienced by others are simply a neutral state free of pain.

The form of government Socrates points out the human tendency to corruption by power and thus the road to timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny: concluding that ruling should be left to philosophers, the most just and therefore least susceptible to corruption. That "good city" is depicted as being governed by philosopher-kings; disinterested persons who rule not for their personal enjoyment but for the good of the city-state (polis). The paradigmatic society which stands behind every historical society is hierarchical, but social classes have a marginal permeability; there are no slaves, no discrimination between men and women. In addition to the ruling class of guardians (phulakes) which abolished riches there is a class of private producers (demiourgoi) be they rich or poor. A number of provisions aim to avoid making the people weak: the substitution of a universal educational system for men and women instead of debilitating music, poetry and theatre -- a startling departure from Greek society. These provisions apply to all classes, and the restrictions placed on the philosopher-kings chosen from the warrior class and the warriors are much more severe than those placed on the producers, because the rulers must be kept away from any source of corruption. This warrior ruled society was based on the ancient Greek society in Sparta. In Books V-VI the abolishment of riches among the guardian class (not unlike Max Weber's bureaucracy) leads controversially to the abandonment of the typical family, and as such no child may know his or her parents and the parents may not know their own children. Socrates tells a tale which is the "allegory of the good government". No nepotism, no private goods. The rulers assemble couples for reproduction, based on breeding criteria. Thus, stable population is achieved through eugenics and social cohesion is projected to be high because familial links are extended towards everyone in the City. Also the education of the youth is such that they are taught of only works of writing that encourage them to improve themselves for the state's good, and envision (the) god(s) as entirely good, just, and the author(s) of only that which is good.

In Books VII-X stand Plato's criticism of the forms of government. It begins with the dismissal of timocracy, a sort of authoritarian regime, not unlike a military dictatorship. Plato offers a psychoanalytical explanation of the "timocrat" as one who saw his father humiliated by his mother and wants to vindicate "manliness". The third worst regime is oligarchy, the rule of a small band of rich people, millionaires that only respect money. Then comes the democratic form of government, and its susceptibility to being ruled by unfit "sectarian" demagogues. Finally the worst regime is tyranny, where the whimsical desires of the ruler became law and there is no check upon arbitrariness.

Theory of universals

- See also Problem of universals, Plato's allegory of the cave and The Forms

The Republic contains Plato's Allegory of the cave with which he explains his concept of The Forms as an answer to the problem of universals.

The allegory of the cave is an attempt to justify the philosopher's place in society as king. Plato imagines a group of people who have lived in a cave all of their lives, chained to a wall in the subterranean so they cannot see outside nor look behind them. Behind these prisoners is a constant flame that illuminates various statues that are moved by others, which cause shadows to flicker around the cave. When the people of the cave see these shadows they realize how imitative they are of human life, and begin to ascribe forms to these shadows such as either "dog" or "cat". The shadows are as close as the prisoners get to seeing reality, according to Plato.

Plato then goes on to explain how the philosopher is a former prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall are not constitutive of reality at all. He sees that the fire and the statues which cause the shadows are indeed more real than the shadows themselves, and therefore apprehends how the prisoners are so easily deceived. Plato then imagines that the freedman is taken outside of the cave and into the real world. The prisoner is initially blinded by the light. However when he adjusts to the brightness, he eventually understands that all of the real objects around him are illuminated by the sun (which represents the Form of the Good, the form which has caused the brightness). He also realizes it is the sun to which he is indebted for being able to see the beauty and goodness in the objects around him. The freedman is finally cognizant that the fire and statues in the cave were just copies of the real objects in the world.

The prisoner's stages of understanding correlate with the levels on the divided line that Plato imagines. The line is divided into what is the visible world, and what the intelligible world is, with the divider being the Sun. When the prisoner is in the cave, he is obviously in the visible realm that receives no sunlight, and outside he comes to be in the intelligible realm.

The shadows in the cave that the prisoners can see correspond to the lowest level on Plato's line, that of imagination and conjecture. Once the prisoner is freed and spots the fire's reflection onto the statues which causes the shadows in the cave, he reaches the second stage on the divided line, and that is the stage of belief, as the freedman comes to believe that the statues in the cave are real as can be. On leaving the cave however the prisoner comes to see objects more real than the statues inside of the cave, and this correlates with the third stage on Plato's line as being understanding. The prisoner is therefore able to ascribe Forms to objects as they exist outside of the cave. Lastly, the prisoner turns to the sun which he grasps as the source of truth, or the Form of the Good, and this last stage, named as dialectic, is the highest possible stage on the line. The prisoner, as a result of the Form of the Good, can begin to understand all other forms in reality.

Allegorically, Plato reasons that the freedman is the philosopher, who is the only person able to discern the Form of the Good, and thus absolute goodness and truth. At the end of this allegory, Plato asserts that it is the philosopher's burden to reenter the cave. Those who have seen the ideal world, he says, have the duty to educate those in the material world, or spread the light to those in darkness. Since the philosopher is the only one able to recognize what is truly good, and only he can reach the last stage on the divided line, only he is fit to rule society according to Plato.

The Dialectical Forms of Government

Plato spends much of "The Republic" narrating conversations about the Ideal State. But what about other forms of government? The discussion turns to four forms of government that cannot sustain themselves: timocracy, oligarchy (also called plutocracy), democracy, and tyranny (also called despotism).

Timocracy

Socrates defines a timocracy as a government ruled by people who love honor and are selected according to the degree of honor they hold in society. Honor is often equated with wealth and possession so this kind of gilded government leads to the people valuing materialism above all things.

Oligarchy

These temptations create a confusion between economic status and honor which is responsible for the emergence of oligarchy. In Book VIII, Socrates suggests that wealth will not help a pilot to navigate his ship. This injustice divides the rich and the poor, thus creating an environment for criminals and beggars to emerge. The rich are constantly plotting against the poor and vice versa.

Democracy

As this socioeconomic divide grows, so do tensions between social classes. From the conflicts arising out of such tensions, democracy replaces the oligarchy preceding it. The poor overthrow the inexperienced oligarchs and soon grant liberties and freedoms to citizens. A visually appealing demagogue is soon lifted up to protect the interests of the lower class. However, with too much freedom, the people become drunk, and tyranny takes over.

Tyranny

The excessive freedoms granted to the citizens of a democracy ultimately leads to a tyranny, the furthest regressed type of government. These freedoms divide the people into three socioeconomic classes: the dominating class, the capitalists and the commoners. Tensions between the dominating class and the capitalists causes the commoners to seek out protection of their democratic liberties. They invest all their power in their democratic demagogue, who, in turn, becomes corrupted by the power and becomes a tyrant with a small entourage of his supporters for protection and absolute control of his people.

Ironically, the ideal state outlined by Socrates closely resembles a tyranny, but they are on opposite ends of the spectrum. This is because the philosopher king who rules in the ideal state is not self-centered but is dedicated to the good of the state insofar as the philosopher king is the one with knowledge.

Reception and interpretation

Ancient Greece

The idea of writing treatises on systems of government was followed some decades later by Plato's most prominent pupil Aristotle. He wrote a treatise for which he used another Greek word "politika" in the title. The title of Aristotle's work is conventionally translated to "politics": see Politics (Aristotle).

Aristotle's treatise was not written in dialogue format: it systematises many of the concepts brought forward by Plato in his Republic, in some cases leading the author to a different conclusion as to what options are the most preferable.

It has been suggested that Isocrates parodies the Republic in his work Busiris by showing Callipolis' similarity to the Egyptian state founded by a king of that name.[8]

Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, wrote his own imitation of Plato's Republic, c. 300 BC. Zeno's Republic advocates a form of anarchism in which all of the citizens are philosophers, and advocates a more radical form of sexual communism than that proposed by Plato.

Ancient Rome

Cicero

The English translation of the title of Plato's dialogue is derived from Cicero's De re publica, a dialogue written some three centuries later. Cicero's dialogue imitates the style of the Platonic dialogues, and treats many of the topics touched upon in Plato's Republic. Scipio Africanus, the main character of Cicero's dialogue expresses his esteem for Plato and Socrates when they are talking about the "Res publica". "Res publica" is not an exact translation of the Greek word "politeia" that Plato used in the title of his dialogue: "politeia" is a general term indicating the various forms of government that could be used and were used in a Polis or city-state.

While in Plato's Republic Socrates and his friends discuss the nature of the city and are engaged in providing the foundations of every state they are living in (which was Athenian democracy, oligarchy or tyranny - in Cicero's De re publica all comments, are more parochial about (the improvement of) the organisation of the state the participants live in, which was the Roman Republic in its final stages.

Tacitus

In antiquity, Plato's works were largely acclaimed; still, some commentators had another view. Tacitus, not mentioning Plato or The Republic nominally in this passage (so his critique extends, to a certain degree, to Cicero's Republic and Aristotle's Politics as well, to name only a few), noted the following (Ann. IV, 33):

| Nam cunctas nationes et urbes populus aut primores aut singuli regunt: delecta ex iis (his) et consociata (constituta) rei publicae forma laudari facilius quam evenire, vel si evenit, haud diuturna esse potest. | Indeed, a nation or city is ruled by the people, or by an upper class, or by a monarch. A government system that is invented from a choice of these same components is sooner idealised than realised; and even if realised, there will be no future for it. |

The point Tacitus develops in the paragraphs immediately preceding and following that quote is that the minute analysis and description of how a real state was governed, as he does in his Annals, however boring the related facts might be, has more practical lessons about good vs. bad governance, than philosophical treatises on the ideal form of government have.

Augustine

In the pivotal era of Rome's move from its ancient polytheist religion to Christianity, Augustine wrote his magnum opus The City of God: again, the references to Plato, Aristotle and Cicero and their visions of the ideal state were legion: Augustine equally described a model of the "ideal city", in his case the eternal Jerusalem, using a visionary language not unlike that of the preceding philosophers.

20th Century

Most 20th century commentators of Plato's Republic advise against reading it as a (would-be) manual for good governance: most forms of government discussed in The Republic bear little resemblance to more recent state organisations like (modern) republics or constitutional monarchies. However, many dictatorships have similar systems. Also, the concepts of democracy and of Utopia as depicted in The Republic are tied to the city-states of ancient Greece and their relevance to modern states is questionable.

Gadamer

In his 1934 Plato und die Dichter (Plato and the Poets), as well as several other works, Hans-Georg Gadamer describes the utopic city of The Republic as a heuristic utopia that should not be pursued or even be used as an orientation-point for political development. Rather, its purpose is said to be to show how things would have to be connected, and how one thing would lead to another — often with highly problematic results — if one would opt for certain principles and carry them through rigorously. This interpretation argues that large passages in Plato's writing are ironic, a line of thought initially pursued by Kierkegaard.

Popper

The city portrayed in The Republic struck some critics as unduly harsh, rigid, and unfree; indeed, as a kind of precursor to modern totalitarianism. Karl Popper gave a voice to that view in his 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies. Popper singled out Plato's state as a utopia which was argued by Plato to be the destiny of man. In particular, Popper thought Plato's envisioned state had totalitarian features as it advocated a government not elected by its citizens, with the identification of the ruling class' interests as being the fate and direction of the state. In addition, Plato's state aimed at autarky, and advocated censorship according to Popper.[9]

Voegelin

Eric Voegelin in Plato and Aristotle (Baton Rouge, 1957), gave meaning to the concept of ‘Just City in Speech’ (Books II-V). For instance, there is evidence in the dialogue that Socrates himself would not be a member of his 'ideal' state. His life was almost solely dedicated to the private pursuit of knowledge. More practically, Socrates suggests that members of the lower classes could rise to the higher ruling class, and vice versa, if they had ‘gold’ in their veins. It is a crude version of the concept of social mobility. The exercise of power is built on the ‘Noble Lie’ that all men are brothers, born of the earth, yet there is a clear hierarchy and class divisions. There is a tri-partite explanation of human psychology that is extrapolated to the city, the relation among peoples. There is no family among the guardians, another crude version of Max Weber's concept of bureaucracy as the state non-private concern.

Strauss and Bloom

Some of Plato’s proposals have led theorists like Leo Strauss and Allan Bloom to ask readers to consider the possibility that Socrates was creating not a blueprint for a real city, but a learning exercise for the young men in the dialogue. There are many points in the construction of the "Just-City-in-Speech" that seem contradictory, which raise the possibility Socrates is employing irony to make the men in the dialogue question for themselves the ultimate value of the proposals. In turn, Plato has immortalized this ‘learning exercise’ in The Republic.

One of many examples is that Socrates calls the marriages of the ruling class 'sacred'; however, they last only one night and are the result of manipulating and drugging couples into predetermined intercourse with the aim of eugenically breeding guardian-warriors. Strauss and Bloom's interpretations, however, involve more than just pointing out inconsistencies; by calling attention to these issues they ask readers to think more deeply about whether Plato is being ironic or genuine, for neither Strauss nor Bloom present an unequivocal opinion, preferring to raise philosophic doubt over interpretive fact.

Leo Strauss's approach developed out a belief that Plato wrote esoterically. The basic acceptance of the exoteric-esoteric distinction revolves around whether Plato really wanted to see the "Just-City-in-Speech" of Books V-VI come to pass, or whether it is just an allegory. Strauss never regarded this as the crucial issue of the dialogue. He argued against Karl Popper's literal view, citing Cicero's opinion that the Republic's true nature was to bring to light the nature of political things.[10] In fact, Strauss undermines the justice found in the "Just-City-in-Speech" by implying the city is not natural, it is a man-made conceit that abstracts away from the erotic needs of the body. The city founded in the Republic "is rendered possible by the abstraction from eros."[11]

An argument that has been used against ascribing ironic intent to Plato is that Plato's Academy produced a number of tyrants, men who seized political power and abandoned philosophy for ruling a city. Despite being well-versed in Greek and having direct contact with Plato himself, some of Plato's former students like Klearchos, tyrant of Heraklia, Chairon, tyrant of Pellene, Eurostatos and Choriskos, tyrants of Skepsis, Hermias of Atarneus and Assos, and Kallipos, tyrant of Syracuse ruled people and did not impose anything like a philosopher-kingship. However, it can be argued whether these men became "tyrants" through studying in the Academy. Plato's school had an elite student body, part of which would by birth, and family expectation, end up in the seats of power. Additionally, it is important to remember that it is by no means obvious that these men were tyrants in the modern, totalitarian sense of the concept. Finally, since very little is actually known about what was taught at Plato's Academy, there is no small controversy over whether it was in fact even in the business of teaching politics at all.[12]

Views on the city-soul analogy

Some critics (like Julia Annas) have adhered to this premise that the dialogue's entire political construct exists to serve as an analogy for the individual soul, in which there are also various potentially competing or conflicting "members" that might be integrated and orchestrated under a just and productive "government."

Practicality

All these 20th century views have something in common: in spite of the near-impossibility of grasping the meanings of the ancient Greek for modern readers, the pedagogical value of The Republic is much greater than its practical value. It is a theoretical work, not a set of guidelines for good governance. Plato scholars see it as their task to provide the background knowledge that is needed to gain a fair understanding of what was meant by the author of The Republic. Then the uniqueness of The Republic shows up in the way it clarifies genuine connections of political causes and effects in real life, precisely by providing them with a heuristically rich context.

Nonetheless Bertrand Russell argues that at least in intent, and all in all not so far from what was possible in ancient Greek city-states, the form of government portrayed in The Republic was meant as a practical one by Plato.[13]

See also

- The Form of the Good

- Ship of state

- Metaphor of the sun

- Analogy of the divided line

- Myth of Er

- Philosopher king

- Plato's Republic in popular culture

- Mixed government

- collectivism

- Big Lie

- Noble Lie

Notes

- ↑ Brickhouse, Thomas, and Smith, Nicholas D. Plato (c. 427-347 B.C.E), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, University of Tennessee. Cf. Dating Plato's Dialogues

- ↑ Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

- ↑ See Benjamin Jowett's introduction to his translation of Plato's Republic

- ↑ Cephalus' profession is not mentioned in The Republic, but his shield factory, in which some hundred and twenty slaves worked, is discussed in the speech Against Eratosthenes by his son Lysias.

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand, History of Western Philosophy, begin of Book I, part 2, ch. 14.

- ↑ Danzig, Gabriel, "Rhetoric and the Ring: Herodotus and Plato on the Story of Gyges as a Politically Expedient Tale", Greece & Rome journal, Volume 55, Issue 02, October 2008, Cambridge University Press, 18 August 2008, pp.169-192

- ↑ “Suppose that a short-sighted person had been asked by some one to read small letters from a distance; and it occurred to some one else that they might be found in another place which was larger and in which the letters were larger, …” (368, trans. Jowett)

- ↑ Most recently, Niall Livingstone, A Commentary on Isocrates' Busiris. Mnemosyne Supplement 223. Leiden: Brill, 2001 (see review by David C. Mirhady in Bryn Mawr Classical Review). For earlier consideration of the similarities, see H. Thesleff, Studies in Platonic Chronology, Helsinki 1982, pp. 105f., and C. Eucken, Isokrates, Berlin 1983, pp. 172 ff. Both Thesleff and Eucken entertain the possibility that Isocrates was responding to an earlier version of Republic than the final version we possess.

- ↑ Popper, Karl (1950) The Open Society and Its Enemies, Vol. 1: The Spell of Plato, New York: Routledge, pp. 91-92.

- ↑ History of Political Philosophy, co-editor with Joseph Cropsey, 3rd. ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987,p.68

- ↑ History of Political Philosophy, co-editor with Joseph Cropsey, 3rd. ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987, p.60

- ↑ Malcolm Schofield, "Plato and Practical Politics", in C. Rowe and M. Schofield (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Political Thought, Cambridge University Press 2005, pp. 293-302.

- ↑ Russell, B. (2004) History of Western Philosophy, end of Book I, part 2, ch. 14.

References

- Plato The Republic, (New CUP translation by Tom Griffith and G.R.F. Ferrari into English) ISBN 0-521-48443-X

- Plato Respublica, (New OUP edition of Greek text) ISBN 0-19-924849-4

- Bloom, Allan, The Republic of Plato translated, with notes, and an interpretive essay. 2nd ed. Basic Books: New York, 1991.

- Bruell, Christopher, “On Plato’s Political Philosophy.” Review of Politics 56 (1994) 261-82.

- Russell, Bertrand, History of Western Philosophy. Simon & Schuster: New York, 1946. - See: two chapters to Plato's Republic, plus a preliminary one on the origin of Plato's concepts: Book I, Part 2, Ch. 13-15.

- Sallis, John, Being and Logos: Reading the Platonic Dialogues, 3rd edn. Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1996, ch. 5.

- Strauss, Leo, 'Plato' History of Political Philosophy 3rd ed. University Of Chicago Press: Chicago, p. 34-68 1987.

- Strauss, Leo, The City and Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.

- Voegelin, Eric, Plato and Aristotle, Louisiana University Press, Baton Rouge, 1956.

External links

- Texts of The Republic:

- At filepedia.org: Plato's Republic: Translated by Benjamin Jowett in pdf and word format

- At Libertyfund.org: Plato's Republic: Translated by Benjamin Jowett (1892) with running comments & Stephanus numbers

- At MIT.edu: Plato's Republic: Translated by Benjamin Jowett

- At Perseus Project: Plato's Republic: Translated by Paul Shorey (1935) annotated and hyperlinked text (English and Greek)

- At Project Gutenberg: e-text Plato's Republic: Translated by Benjamin Jowett with introduction.

- RSS version of The Republic

- Ongoing discussions of Plato's text (and Popper's analysis):

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Ethics and Politics in The Republic

- An audio book The Republic by Plato. A BitTorrent download, 50 MB, MP3 format