The Picture of Dorian Gray

| The Picture of Dorian Gray | |

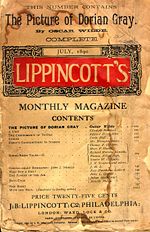

Cover of the first edition |

|

| Author | Oscar Wilde |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Gothic Novel |

| Publisher | Lippincott's Monthly Magazine |

| Publication date | 1890 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | ISBN 0-14-143957-2 (Modern paperback edition) |

The Picture of Dorian Gray is the only published novel written by Oscar Wilde, first appearing as the lead story in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine on 20 June 1890.[1] Wilde later revised this edition, making several alterations, and adding new chapters; the amended version was published by Ward, Lock, and Company in April 1891.[2] The story is often miscalled The Portrait of Dorian Gray.

The novel tells of a young man named Dorian Gray, the subject of a painting by artist Basil Hallward. Basil is greatly impressed by Dorian's physical beauty and becomes strongly infatuated with him, believing that his beauty is responsible for a new mode in his art. Talking in Basil's garden, Dorian meets Lord Henry Wotton, a friend of Basil's, and becomes enthralled by Lord Henry's world view. Espousing a new kind of hedonism, Lord Henry suggests that the only thing worth pursuing in life is beauty, and the fulfilment of the senses. Realising that one day his beauty will fade, Dorian cries out, wishing that the portrait Basil has painted of him would age rather than himself. Dorian's wish is fulfilled, subsequently plunging him into a series of debauched acts. The portrait serves as a reminder of the effect each act has upon his soul, with each sin being displayed as a disfigurement of his form, or through a sign of aging.[3]

The Picture of Dorian Gray is considered one of the last works of classic gothic horror fiction with a strong Faustian theme.[4] It deals with the artistic movement of the decadents, and homosexuality, both of which caused some controversy when the book was first published. However, in modern times, the book has been referred to as "one of the modern classics of Western literature."[5]

Contents |

Plot summary

The novel begins with Lord Henry Wotton observing the artist Basil Hallward painting the portrait of a handsome young man named Dorian Gray. Dorian arrives later, meeting Wotton. After hearing Lord Henry's world view, Dorian begins to think that beauty is the only worthwhile aspect of life, and the only thing left to pursue. He wishes that the portrait of himself, which Basil is painting, would grow old in his place. Under the influence of Lord Henry, Dorian begins an exploration of his senses. He discovers an actress, Sibyl Vane, who performs Shakespeare in a dingy theatre. Dorian approaches her, and soon proposes marriage. Sibyl, who refers to him as "Prince Charming," rushes home to tell her skeptical mother and brother. Her protective brother, James, tells her that if "Prince Charming" ever harms her, he will kill him.

Dorian then invites Basil and Lord Henry to see Sibyl perform in Romeo and Juliet. Sibyl, whose only previous knowledge of love was through the love of theatre, suddenly loses her acting abilities through the experience of true love with Dorian, and performs very badly. Dorian rejects her, saying that her beauty was in her art, and if she could no longer act, he was no longer interested in her. When he returns home, Dorian notices that Basil's portrait of him has changed. After examining the painting, Dorian realizes that his wish has come true - the portrait's expression now bears a subtle sneer, and will age with each sin he commits, while his own outward appearance remains unchanged. He decides to reconcile with Sibyl, but Lord Henry arrives in the morning to say that Sibyl has killed herself by swallowing prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide). Over the next eighteen years, Dorian experiments with every vice, mostly under the influence of a "poisonous" French novel, a present from Lord Henry. Wilde never reveals the title but his inspiration was possibly drawn from Joris-Karl Huysmans's À rebours (Against Nature) due to the likenesses that exist between the two novels.[6]

One night, before he leaves for Paris, Basil arrives to question Dorian about the rumours of his indulgences. Dorian does not deny his debauchery. He takes Basil to the portrait, which is revealed to have become as hideous as Dorian's sins. In a fit of anger, Dorian blames the artist for his fate, and stabs Basil to death. He then blackmails an old friend named Alan Campbell, who is a chemist, into destroying Basil's body. Wishing to escape his crime, Dorian travels to an opium den. James Vane is nearby, and hears someone refer to Dorian as "Prince Charming." He follows Dorian outside and attempts to shoot him, but he is deceived when Dorian asks James to look at him in the light, saying that he is too young to have been involved with Sibyl eighteen years ago. James releases Dorian, but is approached by a woman from the opium den, who chastises him for not killing Dorian and tells him that Dorian has not aged for the past eighteen years.

While at dinner one night, Dorian sees Sibyl Vane's brother stalking the grounds and fears for his life. However, during a game-shooting party the next day, James is accidentally shot and killed by one of the hunters. After returning to London, Dorian informs Lord Henry that he will be good from now on, and has started by not breaking the heart of his latest innocent conquest, a vicar's daughter in a country town, named Hetty Merton. At his apartment, Dorian wonders if the portrait has begun to change back, losing its senile, sinful appearance, now that he has changed his immoral ways. He unveils the portrait to find that it has become worse. Seeing this, he begins to question the motives behind his act of "mercy," whether it was merely vanity, curiosity, or the quest for new emotional excess. Deciding that only a full confession would truly absolve him, but lacking any feelings of guilt and fearing the consequences, he decides to destroy the last vestige of his conscience. In a fit of rage, he picks up the knife that killed Basil Hallward, and plunges it into the painting. His servants hear a cry from inside the locked room and send for the police. They find Dorian's body, suddenly aged, withered and horrible, beside the portrait, which has reverted to its original form; it is only through the rings on his hand that the corpse can be identified.

Characters

In a letter, Wilde stated that the main characters of The Picture of Dorian Gray are in different ways reflections of himself: "Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry what the world thinks me: Dorian what I would like to be—in other ages, perhaps."[7]

- Dorian Gray - an extremely handsome young man who becomes enthralled with Lord Henry's idea of a new hedonism. He begins to indulge in every kind of pleasure, moral and immoral.

- Basil Hallward - an artist who becomes infatuated with Dorian's beauty. Dorian helps Basil to realise his artistic potential, as Basil's portrait of Dorian proves to be his finest work.

- Lord Henry Wotton - a nobleman who is a friend to Basil initially, but later becomes more intrigued with Dorian's beauty and naivete. Extremely witty, Lord Henry is seen as a critique of late Victorian culture espousing a view of indulgent hedonism. He corrupts Dorian with his world view, as Dorian attempts to emulate him. Basil calls him "Harry".

- Sibyl Vane - An exceptionally talented (though extremely poor) and beautiful actress with whom Dorian falls in love. Her love for Dorian destroys her acting career, as she no longer finds pleasure in portraying fictional love when she has a true love in reality.

- James Vane - Sibyl's brother who is to become a sailor and leave for Australia. He is extremely protective of his sister, especially as his mother is useless and concerned only with Dorian's money. He is hesitant to leave his sister, believing Dorian will harm her.

- Mrs. Vane - Sibyl and James's mother, an old and faded actress. She has consigned herself and Sibyl to a poor theatre house to pay her debts. She is extremely pleased when Sibyl meets Dorian, being impressed by the promise of his status and wealth.

- Alan Campbell - once a good friend of Dorian, he ended their friendship when Dorian's reputation began to come into question.

- Lady Agatha - Lord Henry’s aunt. Lady Agatha is active in charity work in the London slums.

- Lord Fermor - Lord Henry's uncle. He informs Lord Henry about Dorian's lineage.

- Victoria, Lady Henry Wotton - Lord Henry's wife, who only appears once in the novel while Dorian waits for Lord Henry. She later divorces Lord Henry in exchange for a pianist.

- Victor - a loyal servant to Dorian. Dorian's increasing paranoia, however, leads him to use Victor to complete pointless errands in an attempt to dissuade him from entering the room that houses Dorian's portrait.

Themes

Aestheticism and duplicity

Aestheticism is a strong theme in The Picture of Dorian Gray, and is tied in with the concept of the double life. Although Dorian is hedonistic, when Basil accuses him of making Lord Henry's sister's name a "by-word", Dorian replies "Take care, Basil. You go too far"[8] suggesting that Dorian still cares about his outward image and standing within Victorian society. Wilde highlights Dorian's pleasure of living a double life,[9] Not only does Dorian enjoy this sensation in private, but he also feels "keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life" when attending a society gathering just 24 hours after committing a murder.

This duplicity and indulgence is most evident in Dorian's visits to the opium dens of London. Wilde conflates the images of the upper class and lower class by having the supposedly upright Dorian visit the impoverished districts of London. Lord Henry asserts that "crime belongs exclusively to the lower orders...I should fancy that crime was to them what art is to us, simply a method of procuring extraordinary sensations", which suggests that Dorian is both the criminal and the aesthete combined in one man. This is perhaps linked to Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which Wilde admired.[1] The division that was witnessed in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, although extreme, is evident in Dorian Gray, who attempts to contain the two divergent parts of his personality. This is a recurring theme in many of the Gothic novels of which The Picture of Dorian Gray is one of the last.

Homoeroticism

The name "Dorian" has connotations of the Dorians, an ancient Greek tribe. Robert Mighall suggests that this could be Wilde hinting at a connection to "Greek love", a euphemism for the homoeroticism that was accepted as everyday in ancient Greece. Indeed, Dorian is described using the semantic field of the Greek Gods, being likened to Adonis, a person who looks as if "he were made of ivory and rose-leaves." However, Wilde does not mention any homosexual acts explicitly, and descriptions of Dorian's "sins" are often vague, although there does appear to be an element of homoeroticism in the competition between Lord Henry and Basil, both of whom compete for Dorian's attention. Both of them make comments about Dorian in praise of his good looks and youthful demeanour, Basil going as far to say that "as long as I live, the personality of Dorian Gray will dominate me."[10] However, while Basil is shunned, Dorian wishes to emulate Lord Henry, which in turn, rouses Lord Henry from his "characteristic languor to a desire to influence Dorian, a process that is itself a sublimated expression of homosexuality."[11] Since the only person Dorian claims to have loved is a woman, Sibyl Vane, it is also possible Wilde intended his character to display Greek pansexuality.

The later corruption of Dorian seems to make what was once a boyish charm become a destructive influence. Basil asks why Dorian's "friendship is so fatal to young men", commenting upon the "shame and sorrow" that the father of one of the disgraced boys displays. Dorian only destroys these men when he becomes "intimate" with them, suggesting that the friendships between Dorian and the men in question become more than simply platonic. The shame associated with these relationships is bipartite: the families of the boys are upset that their sons may have indulged in a homosexual relationship with Dorian Gray, and also feel shame that they have now lost their place in society, their names having been sullied; their loss of status is encapsulated in Basil's questioning of Dorian: speaking of the Duke of Perth, a disgraced friend of Dorian's, he asks "what gentleman would associate with him?"[12] The novel is considered groundbreaking in the context that, in literature, "Dorian Gray was one of the first in a long list of hedonistic fellows whose homosexual tendencies secured a terrible fate."[13]

Allusions to other works

The Republic

Glaucon and Adeimantus present the myth of Gyges' ring, by which Gyges made himself invisible. They ask Socrates, if one came into possession of such a ring, why should he act justly? Socrates replies that even if no one can see one's physical appearance, the soul is disfigured by the evils one commits. This disfigured (the antithesis of beautiful) and corrupt soul is imbalanced and disordered, and in itself undesirable regardless of other advantages of acting unjustly. Dorian Gray's portrait is the means by which other individuals, such as Dorian's friend Basil, shortly before Dorian kills him, may see Dorian's distorted soul. The portrait is also akin to Gyges' ring: for by making Dorian eternally youthful and innocent in appearance, he may commit crimes with impunity.

Tannhäuser

At one point, Dorian Gray attends a performance of Richard Wagner's opera, Tannhäuser, and is explicitly said to personally identify with the work. Indeed, the opera bears some striking resemblances with the novel, and, in short, tells the story of a medieval (and historically real) singer, whose art is so beautiful that he causes Venus, the goddess of love herself, to fall in love with him, and to offer him eternal life with her in the Venusberg. Tannhäuser becomes dissatisfied with his life there, however, and elects to return to the harsh world of reality, where, after taking part in a song-contest, he is sternly censured for his sensuality, and eventually dies in his search for repentance and the love of a good woman. It might even be argued that the end of the opera, in which a miracle announces the salvation of Tannhäuser's soul, suggests, perhaps, a more optimistic interpretation of Dorian's end than might otherwise be thought of.

Faust

Wilde himself stated that "in every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or Faust." As in Faust, a temptation is placed before the lead character Dorian, the potential for ageless beauty; Dorian indulges in this temptation. In both stories, the lead character entices a beautiful woman to love them and kills not only her, but also that woman's brother, who seeks revenge.[14] Wilde went on to say that the notion behind The Picture of Dorian Gray is "old in the history of literature" but was something to which he had "given a new form".[15]

Unlike Faust, there is no point at which Dorian makes a deal with the devil. However, Lord Henry's cynical outlook on life, and hedonistic nature seems to be in keeping with the idea of the devil's role, that of the temptation of the pure and innocent, qualities which Dorian exemplifies at the beginning of the book. Although Lord Henry takes an interest in Dorian, it does not seem that he is aware of the effect of his actions. However, Lord Henry advises Dorian that "the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing";[16] in this sense, Lord Henry acts as the devil's advocate, "leading Dorian into an unholy pact by manipulating his innocence and insecurity."[17] (NB: the Cliff's Notes reference[17] misuses the term: a devil's advocate is a "professional skeptic," one who takes a position to help in evaluating all sides of a complex argument, not one who "advocates for the Devil.")

Shakespeare

In his preface, Wilde writes about Caliban, a character from Shakespeare's play The Tempest. When Dorian is telling Lord Henry Wotton about his new 'love', Sibyl Vane, he refers to all of the Shakespearean plays she has been in, referring to her as the heroine of each play. At a later time, he speaks of his life by quoting Hamlet.

Joris-Karl Huysmans

Dorian Gray's "poisonous French novel" that leads to his downfall is believed to be Joris-Karl Huysmans' novel À rebours. Literary critic Richard Ellmann writes:

Wilde does not name the book but at his trial he conceded that it was, or almost, Huysmans's A Rebours...To a correspondent he wrote that he had played a 'fantastic variation' upon A Rebours and some day must write it down. The references in Dorian Gray to specific chapters are deliberately inaccurate.[18]

Literary significance

The Picture of Dorian Gray began as a short novel submitted to Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. In 1889, J. M. Stoddart, a proprietor for Lippincott, was in London to solicit short novels for the magazine. Wilde submitted the first version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, which was published on 20 June 1890 in the July edition of Lippincott's. There was a delay in getting Wilde's work to press while numerous changes were made to the manuscripts of the novel (some of which survive to this day). Some of these changes were made at Wilde's instigation, and some at Stoddart's. Wilde removed all references to the fictitious book "Le Secret de Raoul", and to its fictitious author, Catulle Sarrazin. The book and its author are still referred to in the published versions of the novel, but are unnamed.

Wilde also attempted to moderate some of the more homoerotic instances in the book, or instances whereby the intentions of the characters may be misconstrued. In the 1890 edition, Basil tells Henry how he "worships" Dorian, and begs him not to "take away the one person that makes my life absolutely lovely to me." The focus for Basil in the 1890 edition seems to be more towards love, whereas the Basil of the 1891 edition cares more for his art, saying "the one person who gives my art whatever charm it may possess: my life as an artist depends on him." The book was also extended greatly: the original thirteen chapters became twenty, and the final chapter was divided into two new chapters. The additions involved the "fleshing out of Dorian as a character" and also provided details about his ancestry, which helped to make his "psychological collapse more prolonged and more convincing."[19]The character of James Vane was also introduced, which helped to elaborate upon Sibyl Vane's character and background; the addition of the character helped to emphasise and foreshadow Dorian's selfish ways, as James foresees Dorian's character, and guesses upon his future dishonourable actions (the inclusion of James Vane's sub-plot also gives the novel a more typically Victorian tinge, part of Wilde's attempts to decrease the controversy surrounding the book). Another notable change is that, in the latter half of the novel, events were specified as taking place around Dorian Gray's 32nd birthday, on 7 November. After the changes, they were specified as taking place around Dorian Gray's 38th birthday, on 9 November, thereby extending the period of time over which the story occurs. The former date is also significant in that it coincides with the year in Wilde's life during which he was introduced to homosexual practices.

Preface

The preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray was added, along with other amendments, after the edition published in Lippincott's received criticism. Wilde used it to address these criticisms and defend the novel's reputation.[20] It consists of a collection of statements about the role of the artist, art itself, the value of beauty, and serves as an indicator of the way in which Wilde intends the novel to be read, as well as traces of Wilde's exposure to Daoism and the writings of Zhuangzi. Shortly before penning the preface, Wilde reviewed Herbert A. Giles's translation of the writings of the Chinese Daoist philosopher.[21] In his review, he writes:

The honest ratepayer and his healthy family have no doubt often mocked at the dome-like forehead of the philosopher, and laughed over the strange perspective of the landscape that lies beneath him. If they really knew who he was, they would tremble. For Chuang Tsǔ spent his life in preaching the great creed of Inaction, and in pointing out the uselessness of all things.[22]

Criticism

Overall, initial critical reception of the book was poor, with the book gaining "certain notoriety for being 'mawkish and nauseous,' 'unclean,' 'effeminate,' and 'contaminating.'"[23] This had much to do with the novel's homoerotic overtones, which caused something of a sensation amongst Victorian critics when first published. A large portion of the criticism was levelled at Wilde's perceived hedonism, and its distorted views of conventional morality. The Daily Chronicle of 30 June 1890 suggests that Wilde's novel contains "one element...which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it." The Scots Observer of 5 July 1890 asks why Wilde must "go grubbing in muck-heaps?” Wilde responded to such criticisms by curtailing some of the homoerotic tendencies, and by adding six chapters to the book in an effort to add background.[24]

Major changes in the 1891 version from the 1890 first edition

The 1891 version was expanded from 13 to 20 chapters, but also toned down, particularly in some of its too overtly homoerotic aspects. Also, chapters 3, 5, and 15 to 18 are entirely new in the 1891 version, and chapter 13 from the first edition is split in two (becoming chapters 19 and 20).[2]

At his 1895 trials, Wilde testified that some of these changes were because of letters sent to him by Walter Pater. [25]

Deleted or moved passages

- (Basil about Dorian) He has stood as Paris in dainty armor, and as Adonis with huntsman's cloak and polished boar-spear. Crowned with heavy lotus-blossoms, he has sat on the prow of Adrian's barge, looking into the green, turbid Nile. He has leaned over the still pool of some Greek woodland, and seen in the water's silent silver the wonder of his own beauty. (This passage turns up in Basil's speech to Dorian in the 1891 version.)

- (Lord Henry about fidelity) It has nothing to do with our own will. It is either an unfortunate accident, or an unpleasant result of temperament.

- "You don't mean to say that Basil has got any passion or any romance in him?" / "I don't know whether he has any passion, but he certainly has romance," said Lord Henry, with an amused look in his eyes. / "Has he never let you know that?" / "Never. I must ask him about it. I am rather surprised to hear it.

- (describing Basil Hallward) Rugged and straightforward as he was, there was something in his nature that was purely feminine in its tenderness.

- (Basil to Dorian) It is quite true that I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend. Somehow, I had never loved a woman. I suppose I never had time. Perhaps, as Harry says, a really grande passion is the privilege of those who have nothing to do, and that is the use of the idle classes in a country. (the latter remark being part of Lord Henry's dialogue in the 1891 version)

- Some dialogue between Mrs Leaf and Dorian has been cut, which mentions Dorian's fondness for "jam" (which might have been used metaphorically for his sexuality).

- When Basil confronts Dorian: Dorian, Dorian, your reputation is infamous. I know you and Harry are great friends. I say nothing about that now, but surely you need not have made his sister's name a by-word. (That part has been deleted in the 1891 version, and the passage after that has been added.)

Added passages

- Each class would have preached the importance of those virtues, for whose exercise there was no necessity in their own lives. The rich would have spoken on the value of thrift, and the idle grown eloquent over the dignity of labour.

- A grande passion is the privilege of people who have nothing to do. That is the one use of the idle classes of a country. Don't be afraid.

- Faithfulness! I must analyze it some day. The passion for property is in it. There are many things that we would throw away if we were not afraid that others might pick them up.

Film, television, popular culture references and theatrical adaptations

The Picture of Dorian Gray has been the subject of several film remakes.

- According to the BBC, the most notable adaptation was Albert Lewin's 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray,[26] which won an Oscar for "Best Cinematography, Black-and-White". Unfortunately, this movie was found by many to still contain the homosexual undertones that are in the book and a blanket ban was placed on the movie.[27] One of the most noted aspects of this version was Lewin's choice to portray the film in black and white despite the fact that technicolor was available at the time. Instead, he shot the film in black and white, and used a "breathtaking" technicolor effect to show the effects Dorian's actions have on the portrait.[28]

- The BBC created a highly regarded TV version in 1976, with Peter Firth as Dorian Gray.

- In 1983, Tony Maylam,directed a film adaptation where Dorian Gray is played by a woman (Belinda Bauer). The female Dorian Gray is an aspiring actress who sells her soul in exchange for eternal youth. The aging portrait in the original version is replaced by a film reel, with Dorian aging each time the film is watched. The character of Lord Henry is played by Anthony Perkins, except that in this version he is called Henry Lord.[29]

- Dorian Gray was a character portrayed by Stuart Townsend in Stephen Norrington's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, which was based on the graphic novel of the same name, written by Alan Moore. Dorian Gray was not originally included in Moore's graphic novel, and Dorian's inclusion was a decision made by Norrington. A "League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" is assembled in an attempt to stop the villain "The Phantom" from destroying Venice. Dorian Gray is selected for his immortality; however, the film version expands upon the novel by suggesting that not only does the portrait keep Dorian from aging, but also from suffering injuries. In addition, Dorian is unable to look at his own portrait; if he does, then the "spell" will be broken, and his powers will be lost — effectively killing him, as he had already reached an age impossible for any mortal being, as well as suffered numerous injuries. During the film, he is revealed to have had a past relationship with fellow immortal Mina Harker — she, a vampire — but it is later revealed that he is actually a double agent, secretly working for the Phantom, who has stolen his portrait to blackmail him into acquiring samples of the other League members so that he can duplicate their powers. At the conclusion of the film, Dorian fights Mina in a duel, which ends when he is pinned to the wall with his own sword and forced to look at his portrait, turning him to dust in a matter of seconds.[30]

- Dorian-The Remarkable Mister Gray, book, music and lyrics by Randy Bowser, premiered 18 April 2008, and ran through 10 May at the Pentacle Theatrein Salem, Oregon. It has since been picked up by Michael Butler to produce a run in Los Angeles in the Fall of 2008.[31]

- Dorian Gray was mentioned in the chorus of the song "Tears and Rain" by singer/songwriter James Blunt. The lyrics used in the refrain, " Run far far away, find comfort in pain, all pleasure's the same it just keeps me from trouble. Hides my true shape, like Dorian Gray, I've heard what they say but I'm not here for trouble. It's more than just words, it's just tears and rain" has been understood to be the pop star's profession of his awareness of the futility of his habit of seeking refuge in hedonistic lifestyles, yet being unable to find a recourse to any other satisfying alternatives. The despairing quality that characterizes Dorian's self destructive belief that his depravity has placed him beyond salvation can be identified within this melancholic ballad.

- The Faustian theme of The Picture of Dorian Gray has also made it a popular choice for television, being adapted for use as a storyline for episodes in some television series':

- The theme of being able to remain young forever was used in the British science fiction TV show Blake's 7 in the episode Rescue which debuted season 4. In it a character named Dorian forces others to absorb his physical and mental defects via a monster he holds in a cave far beneath the surface of the planet Xenon. When the creature is killed, Dorian dies a horrific death.

- Star Trek: The Next Generation also used the novel as inspiration for its 129th episode Man of the People. In the episode, an Ambassador Ves Alkar uses women as an object to which all of his negative aspects can be channelled. This results in the women's dispositions changing, each becoming more and more irritable. They also begin to age much more quickly, until they "burn out" and die. Deanna Troi becomes a near victim, until a plan is created to cause Ves Alkar to receive all of the emotions he has channelled away from himself. When this occurs, he rapidly ages and dies from his own emotions, much in the same way Dorian Gray does after confronting his portrait at the end of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- An operatic version of The Picture of Dorian Gray was staged by Lowell Liebermann. Liebermann wanted to base a play on The Picture of Dorian Gray because "the book made an impression on [him] as no other book has yet done".[32] Premiered at the Monte Carlo Opera in 1996,[33] Liebermann put a lot of emphasis on the musical score of the play, saying:

The entire opera is based on a twelve-note row which is used not serially, but tonally. It is first heard at the beginning of the opera in pizzicato cellos and basses. It is harmonised as Dorian's theme and then as the painting theme. As the painting disintegrates and becomes corrupted, so does its theme. The twelve consecutive scenes of the opera occur in the keys of the consecutive pitches of the note-row. In this manner the entire opera becomes one grand passacaglia, a variation of Dorian's theme, a picture of the picture---the tonal structure generated by a non-tonal device, a further metaphor for the form/content divide that generates the novel's dramatic structure.

- In 2007 Australian production house Diatomic Productions commissioned playwrights Greg Eldridge and Liam Suckling to adapt the novel into a 3 act play. The world premiere of this work (held on May 22, 2008) sold out its season before Opening Night and returned to a second season of sell-out shows as part of the 2008 Melbourne Fringe Festival in October. Website.

- A musical adaptation of the book by young theatre company Kangaroo Court is currently enjoying a successful run at the Tabard theatre, Chiswick (22nd Oct 2008 - 15th Nov 2008) Cast members include Nick Thompson, David Templeman, Megan Pugh and Gary Richens. This updated version centres on celebrity obsession and excesses and expected to go on a national tour once the current run is complete.

- The afternoon ABC daytime drama Dark Shadows (1966-1971) featured a storyline clearly inspired by Wilde's novel, in which a portrait of Quentin Collins aged grotesquely while Collins himself remained youthful. ABC also presented an adaptation of Dorian Gray itself as a 1973 entry in its Movie of the Week series directed by Glenn Jordan, produced by Dan Curtis and starring Shane Briant.

- The Sins of Dorian Gray is a 1983 ABC television movie featuring Belinda Bauer as an actress whose first screen test as a young starlet ages, while she becomes a star known for remaining unusually youthful.

- Titled Dorian Gray, a modern dance adaptation by Matthew Bourne, the English choreographer best known for his very successful Swan Lake and his more recent dance version of Edward Scissorhands, opened in Edinburgh in August 2008, and moved to Sadlers Wells in London in September 2008. Bourne brings the story forward to 21st-century London, where fashion photographer Basil Hallward discovers the unknown Dorian Gray and makes him into the advertising symbol for a brand of men's cologne. Bourne brings the homoeroticism of the novel to the forefront by switching the genders of two of the principals: Lord Henry Wotton is now Lady H, publisher of a fashion magazine; and most significantly, Sybil Vane has become ballet dancer Cyril Vane, whom Gray falls for after watching a performance of Prokofiev's Romeo & Juliet ballet.

- A new film version called Dorian Gray is currently in production, directed by Oliver Parker. Production started in 2008, but a release date is yet to be announced. The film will star Colin Firth as Lord Henry Wotton and The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian actor Ben Barnes as the handsome Dorian Gray. Other cast members are Ben Chaplin, Rebecca Hall, Fiona Shaw, and Rachel Hurd-Wood.[34]

- In 1943 Ivan Albright was commissioned to create the title painting for Albert Lewin's film adaptation of Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray. His realistic, but exaggerated, depictions of decay and corruption made him very well suited to undertake such a project. His brother was chosen to do the original uncorrupted painting of Gray, but the painting used on the film was from Henrique Medina. Ivan made the changes in the painting during the film. This original painting currently resides in the Art Institute of Chicago.

- The Libertines reference Dorian Gray on their song "Narcissist" on their second album "The Libertines".

Editions

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oneworld Classics 2008, ISBN 978-1-84749-018-6

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Penguin Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0141442037

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oxford World's Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0192807298

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Tor 1999, ISBN 0-812-56711-0

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wordsworth Classics 1992, ISBN 1853260150

Footnotes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Introduction

- ↑ Notes on The Picture of Dorian Gray - An overview of the text, sources, influences, themes and a summary of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- ↑ [1]The Picture of Dorian Gray (Project Gutenberg 20-chapter version), line 3479 et seq in plain text (chapter VII).

- ↑ glbtq >> literature >> Ghost and Horror Fiction - a website which discusses ghost and horror fiction from the 19th century onwards (retrieved 30 July 2006)

- ↑ Books of the poet: Oscar Wilde - a website which gives synopses for several books, including The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 27 August 2006

- ↑ "Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray". Highbeam Research. Retrieved on 2007-04-26.

- ↑ The Modern Library - a synopsis of the book coupled with a short biography of Oscar Wilde (retrieved 6 July 2006)

- ↑ name="DorianGray Chapter XII">The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Chapter XII

- ↑ name="DorianGray Chapter XI">The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Chapter XI

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Chapter I

- ↑ glbtq >> literature >> Wilde, Oscar - an analysis of the works of Oscar Wilde, from an encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer culture (retrieved 29 July 2006)

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Chapter XII

- ↑ Meloy, Kilian (2007-09-24). ""Influential Gay Characters in Literature"". AfterElton.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Oscar Wilde Quotes - a quote from Oscar Wilde about The Picture of Dorian Gray and its likeness to Faust (retrieved 7 July 2006)

- ↑ 'The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Preface

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - Chapter II

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 The Picture of Dorian Gray - a summary and commentary of Chapter II of The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 29 July 2006)

- ↑ Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (Vintage, 1988) p.316

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) - A Note on the Text

- ↑ GraderSave: ClassicNote - a summary and analysis of the book and its preface (retrieved 5 July 2006)

- ↑ The Preface first appeared with the publication of the novel in 1891. But by June of 1890, Wilde was defending his book (see The Letters of Oscar Wilde], Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis eds., Henry Holt (2000), ISBN 0-8050-5915-6 and The Artist as Critic, ed. Richard Ellmann, University of Chicago (1968), ISBN 0-226-89764-8 — where Wilde's review of Giles's translation is incorrectly identified with Confucius.) Wilde's review of Giles's translation was published in The Speaker of 8 February 1890.

- ↑ Ellmann, The Artist as Critic, 222.

- ↑ The Modern Library - a synopsis of the book coupled with a short biography of Oscar Wilde (retrieved 6 July 2006)

- ↑ CliffsNotes::The Picture of Dorian Gray - an introduction and overview the book (retrieved 5 July 2006)

- ↑ Lawler, Donald L., An Inquiry into Oscar Wilde's Revisions of 'The Picture of Dorian Gray' (New York: Garland, 1988)

- ↑ BBC - Films - review - a review of Albert Lewin's film version of The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 27 August 2006

- ↑ Awards for The Picture of Dorian Gray - a list of awards presented to Albert Lewin's film version of The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 27 August 2006)

- ↑ Movie Review - Picture of Dorian Gray, The - a review of Albert Lewin's film version of The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 27 August 2006)

- ↑ imdb.com-DorianGray1983

- ↑ Dorian Gray, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen - an overview of Dorian Gray as he is presented in the film The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (film) (retrieved 27 August 2006)

- ↑ http://rbowser.tripod.com/dorian/statesman-butler-contract.html

- ↑ OperaWorld.com's Opera Insights: The Picture of Dorian Gray - a discussion of The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the play by the same name composed by Lowell Libermann (retrieved 30 August 2006])

- ↑ us Operaweb - The Picture of Dorian Gray - an overview of the operatic version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, with quotes from the composer (retrieved 30 August) 2006

- ↑ Archie Thomas (2008-08-07). "Rebecca Hall joins 'Dorian Gray'", Variety Magazine. Retrieved on 2008-09-12.

See also

- List of cultural references in The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Adaptations of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Dorian Gray Syndrome

External links

- Replica of the 1890 Edition at University of Victoria

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (13-chapter version) at Project Gutenberg

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (20-chapter version) at Project Gutenberg

- The Picture of Dorian Gray at the Internet Movie Database

- Audioversion at Librivox