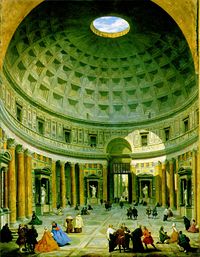

Pantheon, Rome

The Pantheon (Latin Pantheon,[1] from Greek Πάνθειον Pantheon, meaning "Temple of all the gods") is a building in Rome which was originally built as a temple to all the gods of Ancient Rome, and rebuilt circa 125 AD during Hadrian's reign. The intended degree of inclusiveness of this dedication is debated. The generic term pantheon is now applied to a monument in which illustrious dead are buried. It is the best preserved of all Roman buildings, and perhaps the best preserved building of its age in the world. It has been in continuous use throughout its history. The design of the extant building is sometimes credited to the Trajan's architect Apollodorus of Damascus, but it is equally likely that the building and the design should be credited to emperor Hadrian's architects, but not Hadrian himself as many art scholars once thought.[2] Since the 7th century, the Pantheon has been used as a Catholic church. The Pantheon is the oldest standing domed structure in Rome. The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, 43.3 metres (142 ft).

Contents |

History

In the aftermath of the Battle of Actium (31 BC), Agrippa built and dedicated the original Pantheon during his third consulship (27 BC). Agrippa's Pantheon was destroyed along with other buildings in a huge fire in 80 AD. The current building dates from about 125 AD, during the reign of the Emperor Hadrian, as date-stamps on the bricks reveal. It was totally reconstructed with the text of the original inscription ("M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT", standing for Latin: Marcus Agrippa, Lucii filius, consul tertium fecit translated to "'Made by Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, in his third consulship") which was added to the new facade, a common practice in Hadrian's rebuilding projects all over Rome. Hadrian was a cosmopolitan emperor who travelled widely in the East and was a great admirer of Greek culture. He might have intended the Pantheon, a temple to all the gods, to be a kind of ecumenical or syncretist gesture to the subjects of the Roman Empire who did not worship the old gods of Rome, or who (as was increasingly the case) worshipped them under other names. How the building was actually used is not known.

Cassius Dio, a Graeco-Roman senator, consul and author of a comprehensive History of Rome, writing approximately 75 years after the Pantheon's reconstruction, mistakenly attributed the domed building to Agrippa rather than Hadrian. Dio's book appears to be the only near-contemporary writing on the Pantheon, and it is interesting that even by the year 200 there was uncertainty about the origin of the building and its purpose:

Agrippa finished the construction of the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens. (Cassius Dio History of Rome 53.27.2)

The building was repaired by Septimius Severus and Caracalla in 202 AD, for which there is another, smaller inscription. This inscription reads "pantheum vetustate corruptum cum omni cultu restituerunt" ('with every refinement they restored the Pantheon worn by age').

Medieval

In 609 the Byzantine emperor Phocas gave the building to Pope Boniface IV, who converted it into a Christian church and consecrated it to Santa Maria ad Martyres, now known as Santa Maria dei Martiri.

The building's consecration as a church saved it from the abandonment, destruction, and the worst of the spoliation which befell the majority of ancient Rome's buildings during the early medieval period. Paul the Deacon records the spoliation of the building by the Emperor Constans II, who visited Rome in July 663:

Remaining at Rome twelve days he pulled down everything that in ancient times had been made of metal for the ornament of the city, to such an extent that he even stripped off the roof of the church [of the blessed Mary] which at one time was called the Pantheon, and had been founded in honor of all the gods and was now by the consent of the former rulers the place of all the martyrs; and he took away from there the bronze tiles and sent them with all the other ornaments to Constantinople.

Much fine external marble has been removed over the centuries, and there are capitals from some of the pilasters in the British Museum. Two columns were swallowed up in the medieval buildings that abbutted the Pantheon on the east and were lost. In the early seventeenth century, Urban VIII Barberini tore away the bronze ceiling of the portico, and replaced the medieval campanile with the famous twin towers built by Maderno, which were not removed until the late nineteenth century.[3] The only other loss has been the external sculptures, which adorned the pediment above Agrippa's inscription. The marble interior and the great bronze doors have survived, although both have been extensively restored.

Renaissance

Since the Renaissance the Pantheon has been used as a tomb. Among those buried there are the painters Raphael and Annibale Carracci, the composer Arcangelo Corelli, and the architect Baldassare Peruzzi. In the 15th century, the Pantheon was adorned with paintings: the best-known is the Annunciation by Melozzo da Forlì. Architects, like Brunelleschi, who used the Pantheon as help when designing the Cathedral of Florence's dome, looked to the Pantheon as inspiration for their works.

Pope Urban VIII (1623 to 1644) ordered the bronze ceiling of the Pantheon's portico melted down. Most of the bronze was used to make bombards for the fortification of Castel Sant'Angelo, with the remaining amount used by the Apostolic Camera for various other works. It is also said that the bronze was used by Bernini in creating his famous baldachin above the high altar of St. Peter's Basilica, but according to at least one expert, the Pope's accounts state that about 90% of the bronze was used for the cannon, and that the bronze for the baldachin came from Venice.[4]. This led the Roman satirical figure Pasquino to issue the famous proverb: Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini ("What the barbarians did not do, the Barberinis [Urban VIII's family name] did").

In 1747, the broad frieze below the dome with its false windows was “restored,” but bore little resemblance to the original. In the early decades of the twentieth century, a piece of the original, as could be reconstructed from Renaissance drawings and paintings, was recreated in one of the panels.

Modern

Also buried there are two kings of Italy: Vittorio Emanuele II and Umberto I, as well as Umberto's Queen, Margherita. Although Italy has been a republic since 1946, volunteer members of Italian monarchist organisations maintain a vigil over the royal tombs in the Pantheon. This has aroused protests from time to time from republicans, but the Catholic authorities allow the practice to continue, although the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage [2] is in charge of the security and maintenance.

The Pantheon is still used as a church. masses are celebrated there, particularly on important Catholic days of obligation, and weddings.

Structure

The building is circular with a portico of three ranks of huge granite Corinthian columns (eight in the first rank and two groups of four behind) under a pediment opening into the rotunda, under a coffered, concrete dome, with a central opening (oculus), the Great Eye, open to the sky. A rectangular structure links the portico with the rotunda. Though often still drawn as a free-standing building, there was a building at its rear into which it abutted; of this building there are only archaeological remains.

In the walls at the back of the portico were niches, probably for statues of Caesar, Augustus and Agrippa, or for the Capitoline Triad, or another set of gods. The large bronze doors to the cella, once plated with gold, still remain but the gold has long since vanished. The pediment was decorated with a sculpture — holes may still be seen where the clamps which held the sculpture in place were fixed.

The 4,535 metric ton (5,000 tn) weight of the concrete dome is concentrated on a ring of voussoirs 9.1 metres (30 ft) in diameter which form the oculus while the downward thrust of the dome is carried by eight barrel vaults in the 6.4 metre (21 ft) thick drum wall into eight piers. The thickness of the dome varies from 6.4 metres (21 ft) at the base of the dome to 1.2 metres (4 ft) around the oculus. The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, 43.3 metres (142 ft), so the whole interior would fit exactly within a cube (alternatively, the interior could house a sphere 43.3 metres (142 ft) in diameter).[5] The Pantheon holds the record for the largest unreinforced concrete dome. The interior of the roof was possibly intended to symbolize the arched vault of the heavens.[5] The Great Eye at the dome's apex is the source of all light. The oculus also serves as a cooling and ventilation method. During storms, a drainage system below the floor handles the rain that falls through the oculus.

The interior features sunken panels (coffers), which, in antiquity, may have contained bronze stars, rosettes, or other ornaments. This coffering was not only decorative, but also reduced the weight of the roof, as did the elimination of the apex by means of the Great Eye. The top of the rotunda wall features a series of brick-relieving arches, visible on the outside and built into the mass of the brickwork. The Pantheon is full of such devices — for example, there are relieving arches over the recesses inside — but all these arches were hidden by marble facing on the interior and possibly by stone revetment or stucco on the exterior. Some changes have been made in the interior decoration.

It is known from Roman sources that their concrete is made up of a pasty hydrate of lime, with pozzolanic ash (Latin pulvis puteolanum) and lightweight pumice from a nearby volcano, and fist-sized pieces of rock. In this, it is very similar to modern concrete.[5] No tensile test results are available on the concrete used in the Pantheon; however Cowan discussed tests on ancient concrete from Roman ruins in Libya which gave a compressive strength of 2.8 ksi (20 MPa). An empirical relationship gives a tensile strength of 213 psi (1.5 MPa) for this specimen.[6] Finite element analysis of the structure by Mark and Hutchison[7] found a maximum tensile stress of only 18.5 psi (0.13 MPa) at the point where the dome joins the raised outer wall.[8] The stresses in the dome were found to be substantially reduced by the use of successively less dense concrete in higher layers of the dome. Mark and Hutchison estimated that if normal weight concrete had been used throughout the stresses in the arch would have been some 80% higher.

As the best-preserved example of an Ancient Roman monumental building, the Pantheon has been enormously influential in Western Architecture from at least the Renaissance on; starting with Brunelleschi's 42-meter dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, completed in 1436 – the first sizeable dome to be constructed in Western Europe since Late Antiquity. The style of the Pantheon can be detected in many buildings of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; numerous city halls, universities and public libraries echo its portico-and-dome structure. Examples of notable buildings influenced by the Pantheon include: the Panthéon in Paris, the Temple in Dartrey, the British Museum Reading Room, Manchester Central Library, Thomas Jefferson's Rotunda at the University of Virginia, the Rotunda of Mosta, in Malta, Low Memorial Library at Columbia University, New York, the domed Marble Hall of Sanssouci palace in Potsdam, Germany, the State Library of Victoria, and the Supreme Court Library of Victoria, both in Melbourne, Australia, the 52-meter-tall Ottokár Prohászka Memorial Church in Székesfehérvár, Hungary, Holy Trinity Church in Karlskrona by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, Sweden, as well as the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

Transportation presented another problem. Just about everything had to come down the Tiber by boat, including the 16 gray granite columns Hadrian ordered for the Pantheon's pronaos. Each was 39 feet (11.8 m) tall, five feet (1.5 m) in diameter, and 60 tons in weight. Hadrian had these columns quarried at Mons Claudianus in Egypt's eastern mountains, dragged on wooden sledges to the Nile, floated by barge to Alexandria, and put on vessels for a trip across the Mediterranean to the Roman port of Ostia. From there the columns were barged up the Tiber. [9]

Decoration while a Christian church

The present high altar and the apse were commissioned by Pope Clement XI (1700-1721) and designed by Alessandro Specchi. In the apse, a copy of a Byzantine icon of the Madonna is enshrined. The original, now in the Chapel of the Canons in the Vatican, has been dated to the 13th century, although tradition claims that it is much older. The choir was added in 1840, and was designed by Luigi Poletti.

The first niche to the right of the entrance holds a Madonna of the Girdle and St Nicholas of Bari (1686) painted by an unknown artist. The first chapel on the right, the Chapel of the Annunciation, has a fresco of the Annunication attributed to Melozzo da Forli. On the left side is a canvas by Clement Maioli of St Lawrence and St Agnes (1645-1650). On the right wall is the Incredulity of St Thomas (1633) by Pietro Paolo Bonzi.

The second niche has a 15th century fresco of the Tuscan school, depicting the Coronation of the Virgin. In the second chapel is the tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II (died 1878). It was originally dedicated to the Holy Spirit. A competition was held to decide which architect should be given the honor of designing it. Giuseppe Sacconi participated, but lost — he would later design the tomb of Umberto I in the opposite chapel. Manfredio Manfredi won the competition, and started work in 1885. The tomb consists of a large bronze plaque surmounted by a Roman eagle and the arms of the house of Savoy. The golden lamp above the tomb burns in honor of Victor Emmanuel III, who died in exile in 1947.

The third niche has a sculpture by Il Lorenzone of St Anne and the Blessed Virgin. In the third chapel is a 15th-century painting of the Umbrian school, The Madonna of Mercy between St Francis and St John the Baptist. It is also known as the Madonna of the Railing, because it originally hung in the niche on the left-hand side of the portico, where it was protected by a railing. It was moved to the Chapel of the Annunciation, and then to its present position some time after 1837. The bronze epigram commemorated Pope Clement XI's restoration of the sanctuary. On the right wall is the canvas Emperor Phocas presenting the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV (1750) by an unknown. There are three memorial plaques in the floor, one conmmemorating a Gismonda written in the vernacular. The final niche on the right side has a statue of St. Anastasio (1725) by Bernardino Cametti.[10]

On the first niche to the left of the entrance is an Assumption (1638) by Andrea Camassei. The first chapel on the left, is the Chapel of St Joseph in the Holy Land, and is the chapel of the Confraternity of the Virtuosi at the Pantheon. This refers to the confraternity of artists and musicians that was formed here by a 16th-century Canon of the church, Desiderio da Segni, to ensure that worship was maintained in the chapel. The first members were, among others, Antonio da Sangallo the younger, Jacopo Meneghino, Giovanni Mangone, Zuccari, Domenico Beccafumi and Flaminio Vacca. The confraternity continued to draw members from the elite of Rome's artists and architects, and among later members we find Bernini, Cortona, Algardi and many others. The institution still exists, and is now called the Academia Ponteficia di Belle Arti (The Pontifical Academy of Fine Arts), based in the palace of the Cancelleria. The altar in the chapel is covered with false marble. On the altar is a statue of St Joseph and the Holy Child by Vincenzo de Rossi. To the sides are paintings (1661) by Francesco Cozza, one of the Virtuosi: Adoration of the Shepherds on left side and Adoration of the Magi on right. The stucco relief on the left, Dream of St Joseph is by Paolo Benaglia, and the one on the right, Rest during the flight from Egypt is by Carlo Monaldi. On the vault are several 17th-century canvases, from left to right: Cumean Sibyl by Ludovico Gimignani; Moses by Francesco Rosa; Eternal Father by Giovanni Peruzzini; David by Luigi Garzi and finally Eritrean Sibyl by Giovanni Andrea Carlone.

The second niche has a statue of St Agnes, by Vincenco Felici. The bust on the left is a portrait of Baldassare Peruzzi, derived from a plaster portrait by Giovanni Duprè. The tomb of King Umberto I and his wife Margherita di Savoia is in the next chapel. The chapel was originally dedicated to St Michael the Archangel, and then to St. Thomas the Apostle. The present design is by Giuseppe Sacconi, completed after his death by his pupil Guido Cirilli. The tomb consists of a slab of alabaster mounted in gilded bronze. The frieze has allegorical representations of Generosity, by Eugenio Maccagnani, and Munificence, by Arnaldo Zocchi. The royal tombs are maintained by the National Institute of Honour Guards to the Royal Tombs, founded in 1878. They also organize picket guards at the tombs. The altar with the royal arms is by Cirilli.

The third niche holds the mortal remains — his Ossa et cineres, "Bones and ashes", as the inscription on the sarcophagus says — of the great artist Raphael. His fiancée, Maria Bibbiena is buried to the right of his sarcophagus; she died before they could marry. The sarcophagus was given by Pope Gregory XVI, and its insription reads ILLE HIC EST RAPHAEL TIMUIT QUO SOSPITE VINCI / RERUM MAGNA PARENS ET MORIENTE MORI, meaning "Here lies Raphael, by whom the mother of all things (Nature) feared to be overcome while he was living, and while he was dying, herself to die". The epigraph was written by Pietro Bembo. The present arrangement is from 1811, designed by Antonio Munoz. The bust of Raphael (1833) is by Giuseppe Fabris. The two plaques commemorate Maria Bibbiena and Annibale Carracci. Behind the tomb is the statue known as the Madonna del Sasso (Madonna of the Rock) so named because she rests one foot on a boulder. It was commissioned by Raphael and made by Lorenzetto in 1524.

In the Chapel of the Crucifixion, the Roman brick wall is visible in the niches. The wooden crucifix on the altar is from the 15th century. On the left wall is a Descent of the Holy Ghost (1790) by Pietro Labruzi. On the right side is the low relief Cardinal Consalvi presents to Pope Pius VII the five provinces restored to the Holy See (1824) made by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. The bust is a portrait of Cardinal Agostino Rivarola. The final niche on this side has a statue of St. Rasius (S. Erasio) (1727) by Francesco Moderati.[11]

Works modeled on, or inspired by, the Pantheon

- Duomo, Florence, Italy (1436)[12]

- The Rotunda (1822-26), University of Virginia, Virginia, USA

- Low Memorial Library (1895), Columbia University, New York, New York, USA

- The Great Dome, Killian Court (1916), Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

- The "Grand Auditorium", Tsinghua University, Beijing, China (1917)

- The Jefferson Memorial (1939-42), Washington, D.C., USA

- The National Gallery of Art (1938-41), Washington, D.C., USA

See also

- Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

- Panthéon, Paris

- Volkshalle

- List of Roman domes

- List of megalithic sites

References

- ↑ Rarely Pantheum. This rare usage appears in Pliny's Natural History (XXXVI.38) in describing this edifice: Agrippae Pantheum decoravit Diogenes Atheniensis; in columnis templi eius Caryatides probantur inter pauca operum, sicut in fastigio posita signa, sed propter altitudinem loci minus celebrata.

- ↑ Kleiner, Fred S., Christin J. Mamiya. "Gardner's Art Through the Ages: Vol. 1", 2008, p. 280

- ↑ Tod A. Marder, "Alexander VII, Bernini, and the Urban Setting of the Pantheon in the Seventeenth Century" The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 50.3 (September 1991:273-292) p. 275.

- ↑ "Pantheon, The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome". Rodolpho Lanciani.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Roth, Leland M (1992). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, And Meaning. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. p36. ISBN 0064384934.

- ↑ H. W. Cowan, The Master Builders. John Wiley and Son, New York, 1977, p. 56

- ↑ R. Mark and P. Hutchinson, "On the Structure of the Pantheon", Art Bulletin. March 1986

- ↑ Moore, David, "The Pantheon", http://www.romanconcrete.com/docs/chapt01/chapt01.htm, 1999

- ↑ "The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World", edited by Chris Scarre (1999) Thames & Hudson, London

- ↑ Specchi's High Altar for the Pantheon and the Statues by Cametti and Moderati, by Tod A. Marder. The Burlington Magazine (1980) The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd. Page 35.

- ↑ Marder,TA page 35.

- ↑ King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 0701169036.

External links

- Podguides Pantheon, guided tour through the Pantheon on your iPod

- Pantheon Rome, Virtual Panorama and photo gallery

- Pantheon, article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Pantheon, excerpt from Rodolpho Lanciani's The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome Edition MDCCCXCVII

- Roman Concrete Research

- Live Pantheon Webcam

- Pantheon

- Tomás García Salgado, "The geometry of the Pantheon's vault"

- Roman Bookshelf - Views of the Pantheon from the 18th and 19th Century

- Aerial photo

- Photos of the Fountain outside of the Pantheon

- Pantheon at Night, Virtual Reality image of the Pantheon at Night

- Pantheon Project at the Karman Center for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Bern, Switzerland Bibliography, Sections, Laser Scanning Data

- Pantheon, Virtual Tour with map and compass effect by Tolomeus

- Pantheon at Great Buildings/Architecture Week website

- Art & History Pantheon

- Pantheon in the Structurae database

- Thornton, Norman. "PoeticPantheon by Norman T. Thornton" (3D VRML web application to house poetry ergodic / concrete). Retrieved on Oct 3, 2007. Retrieved on 10, 3, 2007.

|

||||||||||||||||||||