Orkney

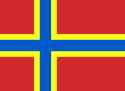

| Orkney Àrcaibh |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

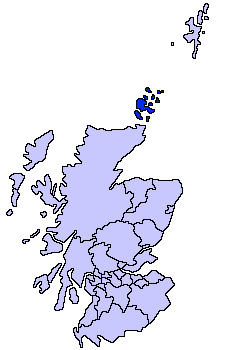

| Location | |||||

|

|||||

| Geography | |||||

| Area | Ranked 16th | ||||

| - Total | 382 sq mi (990 km²) | ||||

| - % Water | ? | ||||

| Admin HQ | Kirkwall | ||||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-ORK | ||||

| ONS code | 00RA | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Population | Ranked 32nd | ||||

| - Total (2007) | 19,900 | ||||

| - Density | 52 /sq mi (20 /km²) | ||||

| Politics | |||||

| Orkney Islands Council http://www.orkney.gov.uk/ |

|||||

| Control | Independent | ||||

| MPs |

|

||||

| MSPs |

|

||||

Orkney (also known as the Orkney Islands or, incorrectly, the Orkneys) is an archipelago in northern Scotland, situated 10 miles (16 km) north of the coast of Caithness. Orkney comprises over 70 islands; around 20 are inhabited. The largest island, known as "Mainland," has an area of 202 sq mi (523 km²), making it the sixth-largest Scottish island and the tenth-largest island in the British Isles. The largest settlement and administrative centre is Kirkwall.

Orkney is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, a constituency of the Scottish Parliament, a lieutenancy area, and a former county. The local council is Orkney Islands Council, the only Council in Scotland in which all the elected members are independent. The local people can be called Orcadians.

Orkney has been inhabited for at least 5,500 years. Originally inhabited by neolithic tribes and then by the Picts, Orkney was invaded and finally annexed by Norway in 875 and settled by the Norse. It was subsequently re-annexed to the Scottish Crown in 1472, following the failed payment of a dowry for James III's bride, Margaret of Denmark.

Orkney contains some of the oldest and best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe, and the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Contents |

Origin of the name

The name of the islands is first recorded by the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemaeus (born AD 90, died AD 168), who called them Orcades. The old Gaelic name for the islands was Insi Orc which means the "Island of the Orcs" ("Arcaibh" in modern Scottish Gaelic). An orc is a young pig or boar. When the Norwegian Vikings arrived on the islands they interpreted the word orc to be orkn which is Old Norse for pinnipeds or common seal. The suffix ey means island. Thus the name became Orkneyjar which was shortened to Orkney in English.

History

Prehistory

A charred hazelnut shell, recovered during the excavations at Longhowe in Tankerness in 2007, has been dated to 6820-6660 BC.[1] Apart from this, the earliest known settlement is at Knap of Howar, a Neolithic farmstead on the island of Papa Westray. It dates from 3500 BC. The village of Skara Brae, Europe's best-preserved Neolithic settlement, is believed to have been inhabited from around 3100 BC. Other remains from that era include the Standing Stones of Stenness, the Maeshowe passage grave, the Ring of Brodgar and other standing stones. Many of the Neolithic settlements were abandoned around 2500 BC due to changes in the climate.

Iron Age

The Iron Age inhabitants were Picts, evidence of whose occupation still exists in "weems" or underground houses, and "brochs" or round towers, such as the Broch of Gurness. During the Roman invasion of Britain the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British leaders who submitted to the Emperor Claudius in AD 43 at Colchester.[2] If, as seems likely, the Dalriadic Gaels established a footing in the islands towards the beginning of the 6th century, their success was short-lived, and the Picts regained power and kept it until dispossessed by the Norsemen in the 9th century. Celtic missionaries inspired by Saint Columba began to arrive about 565. Their efforts to convert the folk to Christianity seem to have impressed the popular imagination, for several islands bear the epithet "Papa" in commemoration of the preachers.

Norwegian rule

Orkney and Shetland saw a significant influx of Norwegian settlers towards the end of the 8th century and first half of the 9th century. This was due to the overpopulation of Norway in comparison to the resources and arable land available there at the time. History once held that the Norwegians largely replaced the original population on the islands, the Picts, though contemporary DNA studies refute this, suggesting instead a slight majority of aboriginal Pictish genes. The nature of the shift in population is the subject of differing theories as little hard evidence remains. These theories range from complete genocide to intermarriage and cultural domination through a gradual majority dominance. According to Dr. Jim Wilson, an Edinburgh scientist, archaeogenetic evidence suggests that "Vikings, who colonised Orkney, did so by eradicating nearly every male member of its Pictish population".[3]

Vikings having made the islands the headquarters of their buccaneering expeditions (also carried out against Norway and the other coasts and isles of Scotland), Harald Hårfagre ("Harald Fair Hair") subdued the rovers in 875 and annexed both Orkney and Shetland to Norway. Ragnvald, Earl of Møre received Orkney and Shetland as an earldom from the king as reparation for his son being killed in battle in Scotland. Ragnvald gave the earldom on to his brother Sigurd the Mighty. Eirik Bloodaxe followed his father on the throne, but when his half-brother Håkon the Good returned to Norway from England Eirik's support disappeared and he fled the country. He was given Nordimbraland (Northumberland) as a fief by King Athelstan of England and settled in Jorvik (York), but was expelled by Athelstan's brother Edmund in 941 because of his raids in Ireland and Brittany. Eirik fled to Orkney and lived there until he was killed in the Battle of Stainmore in England in 954. His sons continued to live on Orkney and challenged Håkon the Good's rule of Norway several times under the leadership of Harald Greyhide. The sons of Eirik eventually gained control of Norway.

The islands were Christianized by Olav Tryggvasson in 995 when he stopped in the islands on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King summoned Sigurd jarl (Earl Sigurd) and ordered him to let himself be baptised in the Christian faith. Sigurd was unwilling, but gave in when the King threatened to kill his son Hvelp. The islands received their own bishop in the early 1000s. From 1153 to 1472 the Kirkjuvåg bishopric was subordinate to the archbishop of Nidaros (today's Trondheim).

The martyrdom of Earl Magnus resulted in the building of St. Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall. The islands remained under the rule of Norse earls until 1231, when the line of the jarls became extinct. In that year, the Earldom of Caithness was granted to Magnus, second son of the Earl of Angus, whom the king of Norway apparently confirmed in the title. Recent studies from the field of population genetics reveal a significant percentage of Norse ethnic heritage — up to one third of the Y chromosomes on the islands are derived from western Norwegian sources, whereas in Shetland over half the male lineage is Norse.

The Norse Kingdom of Mann and the Isles existed in the British Isles from 1079 till 1266. The Kingdom had two parts, Sodor (Old Norse: Suðr-eyjar), or the South Isles (the Hebrides and Mann), and Norðr (Old Norse: Norðr-eyjar), or the North Isles (Orkney and Shetland). The Kings of Mann and the Isles were vassals of the Kings of Norway.

Evidence of the Viking presence is widespread, and includes the settlement at the Brough of Birsay, the vast majority of place names, and runic inscriptions at Maeshowe and other ancient sites.

Scottish rule

In 1468, Orkney and Shetland were pledged by Christian I, in his capacity as king of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland.[4]

Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Riksråd (Council of the Realm) Christian entered into the contract on 8 September 1468 personally with the King of Scotland in which he pawned Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilders.[5] On 28 May the next year he also pawned Shetland for 8,000 Rhenish guilders.[6] He secured a clause in the contract which gave future kings of Norway the right to redeem the islands for a fixed sum of 210 kg of gold or 2,310 kg of silver. Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success.[7]

In 1471, James bestowed the castle and lands of Ravenscraig, in Fife, to William, Earl of Orkney, in exchange for all his rights to the Earldom of Orkney, which, by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland, passed on 20 February 1472, was annexed to the Scottish Crown.

In 1669 an Act of Annexation was passed by the Scottish Parliament establishing Orkney and Shetland as Crown Dependencies following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who then held the estates of both Orkney and Shetland.

The Act made Orkney and Shetland exempt from any "dissolution of His Majesty’s lands". In 1742 a further Act of Parliament returned the estates to a later Earl of Morton, although the 1669 Act specifically proscribed this, stating that any such change is to be "considered null, void and of no effect".

In the 17th century, Orcadians formed the overwhelming majority of employees of the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The harsh climate of the Orkneys and the Orcadian reputation for sobriety made them ideal candidates for the rigours of the Canadian north. Today, many of the Métis people of western Canada trace their history to Orkney.

Modern Orkney

Orkney was the site of a Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow, which played a major role in both World War I and II. After the Armistice in 1918, the German High Seas Fleet was transferred in its entirety to Scapa Flow while a decision was to be made on its future; however, the German sailors opened their sea-cocks and scuttled all the ships. Most ships were salvaged, but the remaining wrecks are now a favoured haunt of recreational divers. One month into World War II, the Royal Navy battleship HMS Royal Oak was sunk by a German U-boat in Scapa Flow. As a result barriers were built to close most of the access channels; these had the additional advantage of creating causeways whereby travellers can go from island to island by road instead of being obliged to rely on boats. The causeways were constructed by Italian prisoners of war, who also constructed the ornate Italian Chapel.

Islands

The Mainland

The Mainland is the largest island of Orkney. Both of Orkney's burghs, Kirkwall and Stromness, are on this island, which is also the heart of Orkney's transportation system, with ferry and air connections to the other islands and to the outside world. The island is more densely populated (75% of Orkney's population) than the other islands and has much fertile farmland. The name Mainland is a corruption of the Old Norse Meginland.

Kirkwall lies on a narrow strip of land between West Mainland (the major portion) and East Mainland. The island is mostly low-lying (especially East Mainland), but with coastal cliffs to the north and west and two sizeable lochs. Mainland contains the remnants of numerous Neolithic, Pictish and Viking constructions. Four of the main Neolithic sites are included in the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site, inscribed in 1999. The group constitutes a major prehistoric cultural landscape which gives a graphic depiction of life in archipelago in the north of Scotland some 5,000 years ago.

The other islands in the group are classified as north or south of the Mainland. Exceptions are the remote islets of Sule Skerry and Sule Stack, which lie 37 miles (60 km) west of the archipelago, but form part of Orkney for local government purposes.

The North Isles

The northern group of islands is the most extensive and consists of a large number of moderately sized islands, linked to the Mainland by ferries. Most of the islands described as "holms" are very small.

Inhabited islands

- Auskerry is south of Stronsay and has a population of 5 (2001 census). It has been designated a Special Protection Area due to its importance as a nesting area for Arctic Tern and Storm Petrel.

- Eday extends to 11 square miles (28 km²); it is the 9th largest island. The centre is moorland and the island's main industries have been peat extraction and limestone quarrying. It is connected to the Mainland by ferry (Backaland to Kirkwall) and air.

- Egilsay lies east of Rousay. It is largely farmland and for the only surviving, but roofless, round-towered church in Orkney. It is connected indirectly with the Mainland by ferry via Wyre and Rousay. St Magnus is said to have been executed on Egilsay.

- Gairsay is inhabited by one family, who issue their own postage stamps (permitted due to the lack of a Royal Mail service).

- North Ronaldsay lies 2.5 miles (4 km) north of its nearest neighbour, Sanday. Its climate is changeable and frequently inclement, with the surrounding waters being stormy and treacherous. Of significance are a bird observatory, Britain's tallest land based lighthouse tower and an unusual dry stane dyke along the shoreline built to keep the seaweed eating North Ronaldsay sheep off of the arable land. It is connected to the Mainland by air and ferry.

- Papa Stronsay lies north east of Stronsay. A fertile island, it was once an important centre for herring curing, but was abandoned in the 1970s. It is has been home to a Transalpine Redemptorist monastery (called Golgotha monastery) since 1999.

- Papa Westray, also known as Papay, has a population of 70. Of significance are an RSPB nature reserve (terns and skuas), the Knap of Howar (probably the oldest preserved house in northern Europe), a 12th century recently restored church (St Boniface Kirk) and other neolithic and Viking remains. It is connected to Westray and the Mainland by air and ferry.

- Rousay is the joint 3rd largest (19 sq mi / 49 km²) island about 2 miles (3 km) north of Orkney's Mainland. In the 2001 census, it had a population of 212. Farming, fishing, fish-farming, craft and tourism provide most of the income. There is one circular road round the island, about 14 miles (23 km) long, and most arable land lies in the few hundred yards between this and the coastline. Seals and otters can be found as can many remains of past occupation.

- Sanday is the largest of the North Isles, with a population of approximately 500. As with most other Orkney islands, farming, fishing and tourism are the main sources of income. Attractions include the 5,000-year-old Quoyness chambered cairn.

- Shapinsay is the 8th largest island at 12 square miles (31 km²). It is connected to the Mainland by ferry (Balfour to Kirkwall). Shapinsay is known for the Iron Age Broch of Burroughston[8] and the Dishan Tower, sea caves and cliffs, for birds including pintail, wigeon and shovelers, and Balfour Castle.

- Stronsay has a population of 343 and is the 7th largest island. Its main village is Whitehall.

- Westray has a population of 550 and is the 6th largest island. It is connected by ferry and air to Mainland and Papa Westray.

- Wyre lies south-east of Rousay and has a population of about 18. Cubbie Roo's castle (1150) is possibly the oldest castle in Scotland.

Others

Other small islands in the North Isles group include: Calf of Eday, Damsay, Eynhallow, Faray, Helliar Holm, Holm of Faray, Holm of Huip, Holm of Papa, Holm of Scockness, Kili Holm, Linga Holm, Muckle Green Holm, Rusk Holm and Sweyn Holm.

The South Isles

The southern group of islands surrounds Scapa Flow. Ward Hill on Hoy is the highest elevation in the Orkney Isles, while South Ronaldsay, Burray and Lamb Holm are linked to the Mainland by the Churchill Barriers. The Pentland Skerries lie further south, close to the Scottish mainland.

Inhabited islands

- Burray lies to the east of Scapa Flow and is linked by causesway to Glimps Holm and South Ronaldsay. It is home to the Orkney Fossil Museum and has a population of 357 (2001 census).

- Flotta is known for its large oil terminal and is linked by ferry to Houton across the Scapa Flow on the Mainland, and to Lyness and Longhope on Hoy. During both World Wars the island was home to a naval base.

- Graemsay has a population of around 30. Birds include oystercatchers, ringed plovers, redshank and curlew. It is linked by ferry to Stromness on the Mainland and Moaness on Hoy.

- Hoy with an area of 55 square miles (142 km²) is the second largest island. Significant features are the highest vertical sea-cliffs in the UK, the Old Man of Hoy, the most northerly surviving natural woodland in the British Isles, the most northerly Martello Towers, the main naval base for Scapa Flow in both World Wars, an unusual rock-cut tomb and an RSPB reserve (skuas and red-throated divers)

- South Ronaldsay is linked by causeway to Burray. With an area of 19 square miles (49 km²) it is the joint third largest island. Of significance are the Boys' Ploughing Match and the Neolithic Tomb of the Eagles. It is connected by ferry to the Scottish mainland (Burwick to John o' Groats and St. Margaret's Hope to Gills Bay).

- South Walls has a population of 120 and is sometimes considered to be part of Hoy, to which it is linked by the Ayre. It forms the south side of Longhope harbour.

Others

Other South Islands include: Calf of Flotta, Cava, Copinsay, Corn Holm, Fara, Glims Holm, Hunda, Lamb Holm, Rysa Little, Switha and Swona.

Politics

Orkney is represented in the House of Commons as part of the Orkney and Shetland constituency, which elects one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election. The current MP is Alistair Carmichael of the Liberal Democrats.

In the Scottish Parliament the Orkney constituency elects one Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) by the first past the post system. The current MSP is Liam McArthur of the Liberal Democrats. Before McArthur the MSP was Jim Wallace, who was previously Deputy First Minister. Orkney is within the Highlands and Islands electoral region.

Orkney Islands Council consists of 21 members, all of whom are independent, that is they are not members of a political party.

The Orkney Movement, a political party that supported devolution for Orkney from the rest of Scotland contested the 1987 UK general election as the Orkney and Shetland Movement (a coalition of the Orkney movement and its equivalent for Shetland). The Scottish National Party chose not to contest the seat to give the movement a "free run". Their candidate, John Goodlad, came 4th with 3,095 votes, 14.5% of the those cast but the experiment has not been repeated.[9][10]

Geography

The Pentland Firth is a seaway which separates Orkney from the mainland of Scotland. The firth is 6.8 miles (11 km) wide between Brough Ness on the island of South Ronaldsay and Duncansby Head in Caithness.

Orkney lies between 58°41′ and 59°24′ North, and 2°22′ and 3°26′ West, measuring 50 miles (80 km) from northeast to southwest and 29 miles (47 km) from east to west, and covers 375 square miles (971 km2). Except for some sharply rising sandstone hills and rugged cliffs on the west of the larger ones, the islands are mainly lowlying.

Other than Hoy, the only other islands containing heights of any importance are the Mainland, with (another) Ward Hill (879 ft/268 m) and Wideford Hill; and Rousay. Nearly all of the islands have lochs (lakes): The Loch of Harray and the Loch of Stenness on the Mainland attain noteworthy proportions. The watercourses are merely streams draining the high land. Excepting on the west fronts of the Mainland, Hoy and Rousay, the coastline of the islands is deeply indented, and the islands themselves are divided from each other by straits generally called "sounds" or "firths". However, off the northeast of Hoy the designation "Bring Deeps" is used. South of the Mainland is Scapa Flow and to the southwest of Eday is found the Fall of Warness.

The names of the islands indicate their nature: the terminal "a" or "ay" represents the Norse ey, meaning "island". The islets are usually styled "holms" and the isolated rocks "skerries".

The tidal currents, or races, or "roosts" (as some of them are called locally, from the Norn) off many of the isles run with high velocity, and whirlpools are of frequent occurrence, occasionally strong enough to prove a source of danger to small craft.

The islands are notable for the absence of trees, which is partly accounted for by the amount of wind. Deliberate deforestation is believed to have taken place at some stage prior to the Neolithic, the use of stone in settlements such as Skara Brae being evidence of the lack of availability of timber for building.

Geology

The superficial rock is almost entirely Old Red Sandstone. As in the neighbouring mainland county of Caithness, these rocks rest upon the metamorphic rocks of the eastern schists, as may be seen on Mainland, where a narrow strip is exposed between Stromness and Inganess, and again in the small island of Graemsay; they are represented by grey gneiss and granite.

The upper division of the Old Red Sandstone is found only on Hoy, where it forms the Old Man of Hoy and neighbouring cliffs on the northwest coast. The Old Man of Hoy presents a characteristic section, for it exhibits a thick pile of massive, current-bedded red sandstones resting upon a thin bed of amygdaloidal porphyrite near the foot of the pinnacle. This, in its turn, lies unconformably upon steeply inclined flagstones. This bed of volcanic rock may be followed northward in the cliffs, and it may be noticed that it thickens considerably in that direction.

The Lower Old Red Sandstone is represented by well-bedded flagstones over most of the islands; in the south of the Mainland these are faulted against an overlying series of massive red sandstones, but a gradual passage from the flagstones to the sandstones may be followed from Westray southeastwards into Eday. A strong synclinal fold traverses Eday and Shapinsay, the axis being North and South. Near Haco's Ness in Shapinsay there is a small exposure of amygdaloidal diabase, which is older than that on Hoy.

Many indications of ice action are found on these islands; striated surfaces are to be seen on the cliffs in Eday and Westray, in Kirkwall Bay and on Stennie Hill in Eday; boulder clay, with marine shells, and with many boulders of rocks foreign to the islands (chalk, oolitic limestone, flint, etc), which must have been brought up from the region of Moray Firth, rests upon the old strata in many places. Local moraines are found in some of the valleys in Mainland and Hoy.

Climate

Orkney has a Maritime Subarctic climate. The climate is remarkably temperate and steady for such a northerly latitude. The average temperature for the year is 8 °C (46 °F), for winter 4 °C (39 °F) and for summer 12 °C (54 °F).

The average annual rainfall varies from 850 mm (33 in) to 940 mm (37 in). Fogs occur during summer and early autumn, and furious gales may be expected four or five times in the year.

To tourists, one of the fascinations of the islands is their nightless summers. On the longest day, the sun rises at 03:00 and sets at 21:29 GMT and darkness is unknown. It is possible to read at midnight and very few stars can be seen in the night sky. Winter, however, is long. On the shortest day the sun rises at 09:05 and sets at 15:16.[11]

Economy

The soil generally is a sandy loam or a strong but friable clay, and very fertile. Large quantities of seaweed as well as lime and marl are available for manure. Most of the land is taken up by farms, and agriculture is by far the most important sector of the economy, with fishing also being a major occupation.

The woollen trade once promised to reach considerable dimensions, but towards the end of the 18th century was superseded by the linen (for which flax came to be largely grown); and when this in turn collapsed before the products of the mills of Dundee, Dunfermline and Glasgow, straw-plaiting was taken up, though only to be killed in due time by the competition of the south. The kelp industry was formerly of at least minor importance.

For several centuries the Dutch practically monopolised the herring fishery, but when their supremacy was destroyed by the salt duty, the Orcadians failed to seize the opportunity thus presented, and George Barry (died 1805) recorded that in his day the fisheries were almost totally neglected. The industry, however, revived, concentrating on herring, cod and ling, but also catching lobsters and crabs.

Today, the traditional sectors of the economy export beef, cheese, whisky, beer, fish and seafood. In recent years there has been growth in other areas including tourism, food and beverage manufacture, jewellery, knitwear, and other crafts production, construction and oil transportation through the Flotta oil terminal. Public services also play a significant role.

Orkney has significant wind, and marine energy resources and renewable energy has recently come into prominence. The European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) is a Scottish Government-backed research facility that has installed a wave testing system at Billia Croo on the Orkney mainland and a tidal power testing station on the island of Eday.[12] At the official opening of the Eday project the site was described as "the first of its kind in the world set up to provide developers of wave and tidal energy devices with a purpose-built performance testing facility.".[13] Funding for the UK's first wave farm was announced by the Scottish Government in 2007. It will be the world's largest, with a capacity of 3 MW generated by four Pelamis machines at a cost of over £4 million.[14] During 2007 Scottish and Southern Energy plc in conjunction with the University of Strathclyde began the implementation of a 'Regional Power Zone' in the Orkney archipelago. This ground-breaking scheme (that may be the first of its kind in the world) involves 'active network management' that will make better use of the existing infrastructure and allow a further 15MW of new 'non-firm generation' output from renewables onto the network.[15][16]

Transport

Air

The main airport in Orkney is Kirkwall Airport, operated by Highland and Islands Airports. Loganair, a franchise of Flybe provides services to the Scottish Mainland (Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Inverness), as well as to Sumburgh Airport in Shetland.

Within Orkney, the council operates airfields on most of the larger islands including Stronsay, Eday, North Ronaldsay, Westray, Papa Westray, and Sanday. The shortest scheduled air service in the world, between the islands of Westray and Papa Westray, is scheduled at two minutes duration but can take less than one minute if the wind is in the right direction.

Ferry

Ferries serve both to link Orkney to the rest of Scotland, and also to link together the various islands of the Orkney archipelago. Ferry services operate between Orkney and the Scottish Mainland and Shetland on the following routes:

- Gills Bay to St Margaret's Hope (operated by Pentland Ferries)

- John o' Groats to Burwick on South Ronaldsay (seasonal passenger only service, operated by John o' Groats Ferries)

- Lerwick to Kirkwall (operated by Northlink Ferries)

- Aberdeen to Kirkwall (operated by Northlink Ferries)

- Scrabster to Stromness (operated by Northlink Ferries)

Inter-island ferry services connect all the inhabited islands to Orkney Mainland, and are operated by Orkney Ferries, a company owned by Orkney Islands Council.

Road

There are ideas being discussed to build an undersea tunnel between Orkney and the Scottish Mainland, at a length of about 9-10 miles (15-16 km) or (more likely) one connecting Orkney Mainland to Shapinsay.[17][18]

Media

Orkney is served by two weekly local newspapers, The Orcadian and Orkney Today,[19] both published every Thursday.

A local BBC radio station, BBC Radio Orkney, the local opt-out of BBC Radio Scotland, broadcasts twice daily, with local news and entertainment. Orkney also has a commercial radio station, The Superstation Orkney which broadcasts to Kirkwall and parts of the mainland, although reception in Stromness and the North Isles is very poor.

Moray Firth Radio broadcasts throughout Orkney on AM and from an FM transmitter just outside Thurso. The community radio station, Caithness FM also broadcasts to most parts of Orkney. Northsound 1 and Northsound 2 can also be heard on parts of the islands, with poor reception.

Sport

The Orkney Amateur Football Association runs leagues between late April and early September, and teams also compete in the Highland Amateur Cup. There are also several Hockey clubs.

Orkney competes in the biannual Island Games.

Language

At the beginning of recorded history the islands were inhabited by the Picts, whose language is unknown. Opinions on the nature of Pictish vary from its having been a Celtic language, to its not having been Indo-European at all. Katherine Forsyth claims that the Ogham script on the Buckquoy spindle-whorl is evidence for the pre-Norse existence of Old Irish in Orkney.[20]

After the Norse occupation the toponymy of Orkney became almost wholly West Norse.[21] The Norse language evolved into the local Norn, which lingered until the end of the 18th century, when it finally died out. Norn was replaced by the Orcadian dialect of Insular Scots. This dialect is at a low ebb due to the constant influences of television, education and the large number of incomers. However attempts are being made to revitalise its use by some writers and radio presenters.[22]

However, the distinctive sing-song accent and many dialect words of Norse origin continue to be used. The Orcadian dialect lingers in the remoter parts of the archipelago. Studies made by Gregor Lamb and others demonstrate the Norse influence on the grammar of Orcadian. The Orcadian word most frequently encountered by visitors is "peedie" ("peerie" in Shetland), meaning "small", which may be derived from the French petit.[23]

Orcadians

- Main article: Orcadians

An Orcadian is a native of Orkney, a term that reflects a strongly held identity with a tradition of understatement.[24]

Although the annexation of the earldom by Scotland in 1472 took place over five centuries ago, most Orcadians regard themselves as Orcadians first and Scots second.[25] (Readers of Scott's The Pirate will remember the frank contempt which Magnus Troil expressed for the Scots).

When an Orcadian speaks of "Scotland", they are talking about the land to the immediate south of the Pentland Firth. When an Orcadian speaks of "the mainland", they mean Mainland, Orkney.[26] They are emphatic that tartan, clans, bagpipes and the like are traditions from the Scottish Highlands and are not a part of the islands' indigenous culture. [27] However, at least two tartans with Orkney connections have been registered and a tartan has been designed for Sanday by one of the island's residents,[28][29] [30] and there are pipe bands in Orkney.[31][32]

Native Orcadians refer to the non-native residents of the islands as "ferry loupers", a term that has been in use for nearly two centuries at least.[33] This designation is celebrated in the Orkney Trout Fishing Association's "Ferryloupers Trophy", suggesting that although it can be used in a derogatory manner, it is more often a light-hearted expression.

Well-known Orcadians

In family name alphabetical order:

- Jim Baikie British comics artist, who is best known for his work with Alan Moore on Skizz.

- William Balfour Baikie (1825-1864), traveller in Africa

- George Mackay Brown (1921-1996), poet, author, playwright

- Mary Brunton (1778-1818), author of Self-Control, Discipline and other novels

- J.Storer Clouston,author

- Stanley Cursiter (1887-1976), artist

- William Towrie Cutt (1898-1981), author

- Walter Traill Dennison (1826-1894), Orcadian folklorist

- Kris Drever, folk singer and guitarist

- Magnus Erlendsson (Saint Magnus) (c.1070-c.1117), Earl of Orkney c.1105-1117

- Matthew Forster Heddle (1828-1897), mineralogist, author of The Mineralogy of Scotland

- Malcolm Laing (1762-1818), author of the History of Scotland from the Union of the Crowns to the Union of the Kingdoms

- Samuel Laing (1780-1868), author of A Residence in Norway, and translator of the Heimskringla, the Icelandic chronicle of the kings of Norway

- Samuel Laing (1812-1897), chairman of the London, Brighton & South Coast railway, and introducer of the system of "parliamentary" trains with fares of one penny a mile

- Magnus Linklater (b.1942), journalist, son of Eric Linklater

- John D Mackay (b.1909), headmaster and Orkney patriot

- Murdoch McKenzie (d.1797), hydrographer

- Edwin Muir (1887-1959), author and poet

- Dr. John Rae (1813-1893), Arctic explorer

- Rognvald Kali Kolsson (Saint Rognvald) (c.1103-1158), Earl of Orkney 1136-1158

- Julyan Sinclair, television presenter

- Thomas Stewart Traill (1781-1862), professor of medical jurisprudence at Edinburgh University and editor of the 8th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Cameron Stout (b.1971) winner of Big Brother in 2003, brother of Julyan Sinclair

- William Walls (1819-1893), lawyer and industrialist

- Wrigley twins Jennifer and Hazel, international folk duo

- Kristin Linklater, born 1946, voice teacher, actor, director and author

People associated with Orkney

- Rev. Matthew Armour (1820-1903), Sanday's radical Free Kirk Minister[34]

- Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (b.1934), composer and Master of the Queen's Music

- Andrew Greig (b.1951), Scottish writer

- Jo Grimond (1913-1993), Liberal Party leader and MP for Orkney and Shetland 1950-1983

- David Harvey (b.1948), footballer

- Eric Linklater (1899-1974), novelist, playwright, journalist, essayist and poet

- William Sichel (b.1951), ultra distance runner

- Max Scratchmann (b.1956), artist and author of "Chucking It All" - seven years in the Orkney Islands

- Luke Sutherland (b.1971), writer of novels Jelly Roll, Sweetmeat and Venus as a Boy

- Jim Wallace, Baron Wallace of Tankerness (b.1954), former MP for Orkney and Shetland (1983-2001), MSP for Orkney (1999-2007), Deputy First Minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats

See also

- List of places in Orkney

- List of Orkney islands

- Bishop of Orkney

- Earl of Orkney

- Orkneyinga saga

- Trow

- Udal Law

- Churchill Barriers

- Italian Chapel

- Orkney vole

- The Superstation - Orkney's Local Radio Station

- Orkney College

- Bere (grain)

References

- ↑ Stone Pages Archaeo News: Hazelnut shell pushes back date of Orcadian site

- ↑ Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. Pages 173-5.

- ↑ The Observer (31 December 2006) London.

- ↑ Acquisition of Orkney and Shetland 1468-9

- ↑ Acquisition of Orkney and Shetland 1468-9

- ↑ University Library, University in Bergen: Article on Shetland (Norwegian)

- ↑ Universitas, Norsken som døde (Norwegian article on the history of the islands) (Norwegian)

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, Burroughston Broch, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham (2007)

- ↑ "Orkney and Shetland Movement" BookRags. Retrieved 11 January 2008

- ↑ "Candidates and Constituency Assessments: Orkney (Highland Region)" alba.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2008

- ↑ "Sunrise and Sunsets" The Orcadian. Shows times for 2006. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ↑ "European Marine Energy Centre". Retrieved on 2007-02-03.

- ↑ Highlands and Islands Enterprise (2007-09-28). "First Minister Opens New Tidal Energy Facility at EMEC". Press release. Retrieved on 2007-10-01. “The centre offers developers the opportunity to test prototype devices in unrivalled wave and tidal conditions. Wave and tidal energy converters are connected to the National Grid via seabed cables running from open-water test berths. Testing takes place in a wide range of sea and weather conditions, with comprehensive round-the-clock monitoring.”

- ↑ "Orkney to get 'biggest' wave farm" BBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- ↑ Registered Power Zone Annual Report for period 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2007 (pdf) Scottish Hydro Electric Power Distribution and Southern Electric Power Distribution. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ FACILITATE GENERATION CONNECTIONS ON ORKNEY BY AUTOMATIC DISTRIBUTION NETWORK MANAGEMENT DTI. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ David Lister (September 5, 2005). "Islanders see a brighter future with tunnel vision", The Times. Retrieved on 2007-07-12.

- ↑ John Ross (10 March 2005). "£100m tunnel to Orkney 'feasible'", The Scotsman. Retrieved on 2007-07-13.

- ↑ Orkney Today Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ↑ Forsyth, Katherine (1995). "The ogham-inscribed spindle-whorl from Buckquoy: evidence for the Irish language in pre-Viking Orkney?". The Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (ARCHway) 125: 677–96. http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/PSAS_2002/pdf/vol_125/125_677_696.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-07-27.

- ↑ Gregor Lamb, Testimony of the Orkneyingar: Place Names of Orkney, 1995, Byrgisey, ISBN 0-9513443-4-X

- ↑ "The Orcadian Dialect" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ↑ Dr.Stephen Clackson, The Orcadian, 25 November 2004

- ↑ Orkneyjar - The people of Orkney

- ↑ The Heart of Neolithic Orkney in its Contemporary Contexts: A case study in heritage management and community values. Historic Scotland Research Paper

- ↑ Orkneyjar - Where is Orkney?

- ↑ Orkneyjar FAQ

- ↑ Orkney tartan

- ↑ Scotsheraldry.com re Sanday Tartan Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- ↑ Clackson tartan

- ↑ Kirkwall City Pipe Band

- ↑ Stromness RBL Pipe Band

- ↑ See: David Vedder, Orcadian Sketches, Edinburgh, William Tait, 1832

- ↑ "Centenary of a radical kirk minister" The Orcadian. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

Further reading

- Warner, Guy (2005) Orkney by Air. Kea Publishing. ISBN 9780951895870

- Lo Bao, Phil and Hutchison, Iain (2002) BEAline to the Islands. Kea Publishing. ISBN 9780951895849

- Fresson, Captain E. E. Air Road to the Isles. (2008) Kea Publishing. ISBN 9780951895894

External links

- Orkney travel guide from Wikitravel

- Orkneycommunities.co.uk- image library, local news and events, directories of community groups and business, websites of community groups

- The Orkney Folk Festival

- The Orcadian, one of Orkney's two local newspapers

- Orkney Today, one of Orkney's two local newspapers

- Orkneyjar, an Orcadian History and Heritage Site

- A recent (June, 2006) photo travelogue on Orkney

- Virtual Orkney: A directory of Orkney

- Vision of Britain - Groome Gazetteer entry for Orkney

|

|||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||