The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of Venice is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. Although classified as a comedy in the First Folio, and while it shares certain aspects with Shakespeare's other romantic comedies, the play is perhaps more remembered for its dramatic scenes, and is best known for the character of Shylock.

The title character is the merchant Antonio, not the Jewish moneylender Shylock, who is the play's most prominent and more famous character. Though Shylock is a tormented character, he is also a tormentor, so whether he is to be viewed with disdain or sympathy is up to the audience (as influenced by the interpretation of the play's director and lead actors). As a result, The Merchant of Venice is often classified as one of Shakespeare's problem plays.

Contents |

Date and text

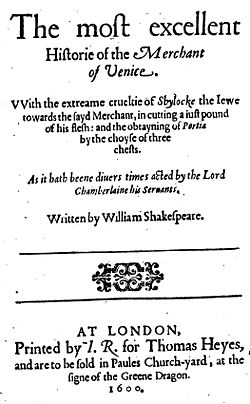

The date of composition for The Merchant of Venice, which draws strongly on Spanish literature,[1] is believed to be between 1596 and 1598. The play was mentioned by Francis Meres in 1598, so it must have been familiar on the stage by that date, and the title page of the first edition in 1600 states that it had been performed "divers times" by that date. Salarino's reference to his ship the "Andrew" (I,i,27) is thought to be an allusion to the Spanish ship St. Andrew captured by the English at Cadiz in 1596. A date of 1596–97 is considered consistent with the play's style.

The play was entered in the Register of the Stationers Company, the method at that time of obtaining copyright for a new play, by James Roberts on July 22, 1598 under the title The Merchant of Venice, otherwise called The Jew of Venice. On October 28, 1600 Roberts transferred his right to the play to the stationer Thomas Hayes; Hayes published the first quarto before the end of the year. It was printed again in a pirated edition in 1619, as part of William Jaggard's so-called False Folio. (Afterward, Thomas Hayes' son and heir Laurence Hayes asked for and was granted a confirmation of his right to the play, on July 8, 1619.) The 1600 edition is generally regarded as being accurate and reliable, and is the basis of the text published in the 1623 in the First Folio, which adds a number of stage directions, mainly musical cues.[2]

The earliest performance of which a record has survived was held at the court of King James in the spring of 1605, followed by a second performance a few days later, but there is no record of any further performances in the seventeenth century.[3] In 1701, George Granville staged a successful adaptation, titled The Jew of Venice, with Thomas Betterton as Bassanio. This version (which featured a masque) was popular, and was acted for the next forty years. Granville cut the Gobbos in line with neoclassical decorum; he added a jail scene between Shylock and Antonio, and a more extended scene of toasting at a banquet scene. Thomas Doggett was Shylock, playing the role comically, perhaps even farcically. Rowe expressed doubts about this interpretation as early as 1709; however, Doggett's success in the role meant that later productions would feature the troupe clown as Shylock.

In 1741 Charles Macklin returned to the original text in a very successful production at Drury Lane, paving the way for Edmund Kean seventy years later (see below).[4]

Characters

- The Duke of Venice

- Prince of Morocco, Prince of Aragon – Portia's suitors

- Antonio – a merchant from Venice

- Bassanio – his friend, in love with Portia

- Portia – a rich Heiress

- Nerissa – her Waiting-maid

- Gratiano, Solanio, Salerio – friends of Antonio and Bassanio

- Lorenzo – in love with Jessica

- Shylock – a rich Jew

- Tubal – a Jew; his Friend

- Jessica – Daughter of Shylock,in love with Lorenzo

- Lancelot Gobbo – a clown servant to Shylock

- Old Gobbo – father to Lancelot

- Leonardo – servant to Bassanio

- Balthazar, Stephano – Servants of Portia

- Magnificoes of Venice, officers of the Court of Justice, Gaoler, servants to Portia, and other Attendants

Synopsis

Bassanio, a young Venetian, would like to travel to Belmont to woo the beautiful and wealthy heiress Portia. He approaches his friend Antonio, a merchant, for three thousand ducats needed to subsidize his traveling expenditures as a suitor for three months. As all of Antonio's ships and merchandise are busy at sea, he promises to cover a bond, so Bassanio turns to the moneylender/usurer Shylock.

Shylock, who hates Antonio because he had insulted and spat on him for being a Jew a week previously, proposes a condition: if Antonio is unable to repay the loan at the specified date, Shylock will be free to take a pound of Antonio's flesh. Although Bassanio does not want Antonio to accept such a risky condition, Antonio, surprised by what he sees as the moneylender's generosity (no "usance" — interest — is asked for), accepts and signs the contract. With money at hand, Bassanio leaves for Belmont with another friend Gratiano.

In Belmont, Portia is awash with suitors. Her father has left a will stipulating each of her suitors must choose correctly from one of three caskets – one each of gold, silver, and lead – before he could win Portia's hand. In order to be granted an opportunity to marry Portia, each suitor must agree in advance to live out his life as a bachelor if he loses the contest. The suitor who correctly looks past the outward appearance of the caskets will find Portia's portrait inside and win her hand.

After two suitors choose incorrectly (the Princes of Morocco and Aragon) Bassanio chooses the leaden casket. He gets it right. The other two contain mocking verses, including the famous phrase all that glisters [glistens] is not gold.

At Venice, all ships bearing Antonio's goods are reported lost at sea, leaving him unable to satisfy the bond. Shylock is even more determined to exact revenge from Christians after his daughter Jessica flees his home to convert to Christianity and elope with the Christian Lorenzo, taking a substantial amount of Shylock's wealth with her. With the bond at hand, Shylock has Antonio arrested and brought before court.

At Belmont, Portia and Bassanio have just been married, along with his friend Gratiano and Portia's handmaid Nerissa. He receives a letter telling him that Antonio has defaulted on his loan from Shylock. Shocked, Bassanio and Gratiano leave for Venice immediately, with money from Portia, to save Antonio's life. Unknown to Bassanio and Gratiano, Portia and Nerissa leave Belmont to seek the counsel of Portia's cousin, Bellario, a lawyer, at Padua.

The dramatic center of the play comes in the court of the Duke of Venice. Shylock refuses Bassanio's offer, despite Bassanio increasing the repayment to 6000 ducats (twice the specified loan). He demands the pound of flesh from Antonio. The Duke, wishing to save Antonio but unwilling to set a dangerous legal precedent of nullifying a contract, refers the case to Balthasar, a young male "doctor of the law" who is actually Portia in disguise, with "his" lawyer's clerk, who is Nerissa in disguise. Portia asks Shylock to show mercy in a famous speech (The quality of mercy is not strained—IV,i,185), but Shylock refuses. Thus the court allows Shylock to extract the pound of flesh.

Shylock tells Antonio to prepare, and at that very moment Portia points out a flaw in the contract (see quibble). The bond only allows Shylock to remove the flesh, not blood, of Antonio. If Shylock were to shed any drop of Antonio's blood in doing so, his "lands and goods" will be forfeited under Venetian laws.

Defeated, Shylock concedes to accepting monetary payment for the defaulted bond, but is denied. Portia pronounces none should be given, and for his attempt to take the life of a citizen, Shylock's property will be forfeited, half to the government and half to Antonio, and his life will be at the mercy of the Duke. The Duke pardons his life before Shylock can beg for it, and Antonio asks for his share "in use" (that is, reserving the principal amount while taking only the income) until Shylock's death, when the principal will be given to Lorenzo and Jessica. At Antonio's request, the Duke grants remission of the state's half of forfeiture, but in return, Shylock is forced to convert to Christianity and to make a will (or "deed of gift") bequeathing his entire estate to Lorenzo and Jessica (IV,i).

Bassanio does not recognize his disguised wife, but offers to give a present to the supposed lawyer. First she declines, but after he insists, Portia requests his ring and his gloves. He gives the gloves away without a second thought, but gives the ring only after much persuasion from Antonio, as earlier in the play he promised his wife never to lose, sell or give it away. Nerissa, as the lawyer's clerk, also succeeds in retrieving her ring from Gratiano.

At Belmont, Portia and Nerissa taunt their husbands before revealing they were really the lawyer and his clerk in disguise.

After all the other characters make amends, all ends happily (except for Shylock) as Antonio learns that three of his ships were not stranded and have returned safely after all.

Performance

Shylock on stage

Jacob Adler and others report that the tradition of playing Shylock sympathetically began in the first half of the 19th century with Edmund Kean[5], and that previously the role had been played "by a comedian as a repulsive clown or, alternatively, as a monster of unrelieved evil." Kean's Shylock established his reputation as an actor.[6]

From Kean's time forward, all of the actors who have famously played the role, with the exception of Edwin Booth, who played Shylock as a simple villain, have chosen a sympathetic approach to the character; even Booth's father, Junius Brutus Booth, played the role sympathetically. Henry Irving's portrayal of an aristocratic, proud Shylock (first seen at the Lyceum in 1879, with Portia played by Ellen Terry) has been called "the summit of his career".[7] Jacob Adler was the most notable of the early 20th century. Adler played the role in Yiddish-language translation, first in Manhattan's Lower East Side, and later on Broadway, where, to great acclaim, he performed the role in Yiddish in an otherwise English-language production.[8]

Kean and Irving presented a Shylock justified in wanting his revenge; Adler's Shylock evolved over the years he played the role, first as a stock Shakespearean villain, then as a man whose better nature was overcome by a desire for revenge, and finally as a man who operated not from revenge but from pride. In a 1902 interview with Theater magazine, Adler pointed out that Shylock is a wealthy man, "rich enough to forgo the interest on three thousand ducats" and that Antonio is "far from the chivalrous gentleman he is made to appear. He has insulted the Jew and spat on him, yet he comes with hypocritical politeness to borrow money of him." Shylock's fatal flaw is to depend on the law, but "would he not walk out of that courtroom head erect, the very apotheosis of defiant hatred and scorn?"[9]

Some modern productions take further pains to show how Shylock's thirst for vengeance has some justification. For instance, in the 2004 film adaptation directed by Michael Radford and starring Al Pacino as Shylock, the film begins with text and a montage of how the Jewish community is cruelly abused by the bigoted Christian population of the city. One of the last shots of the film also brings attention to the fact that, as a convert, Shylock would have been cast out of the Jewish community in Venice, no longer allowed to live in the ghetto, and would still not be accepted by the Christians, as they would feel that Shylock was yet the Jew he once was.

Themes

Shylock and the anti-Semitism debate

The play is frequently staged today, but is potentially troubling to modern audiences due to its central themes, which can easily appear anti-Semitic. Critics today still continue to argue over the play's stance on anti-Semitism.

The anti-Semitic reading

English society in the Elizabethan era has been described as anti-Semitic.[10] English Jews had been expelled in the Middle Ages and were not permitted to return until the rule of Oliver Cromwell. Jews were often presented on the Elizabethan stage in hideous caricature, with hooked noses and bright red wigs, and were usually depicted as avaricious usurers; an example is Christopher Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta, which features a comically wicked Jewish villain called Barabas. They were usually characterized as evil, deceptive, and greedy.

During the 1600s in Venice and in some other places, Jews were required to wear a red hat at all times in public to make sure that they were easily identified. If they did not comply with this rule they could face the death penalty. Jews also had to live in a ghetto protected by Christians, supposedly for their own safety. The Jews were expected to pay their guards. [11]

Readers may see Shakespeare's play as a continuation of this anti-Semitic tradition. The title page of the Quarto indicates that the play was sometimes known as The Jew of Venice in its day, which suggests that it was seen as similar to Marlowe's The Jew of Malta. One interpretation of the play's structure is that Shakespeare meant to contrast the mercy of the main Christian characters with the vengefulness of a Jew, who lacks the religious grace to comprehend mercy. Similarly, it is possible that Shakespeare meant Shylock's forced conversion to Christianity to be a "happy ending" for the character, as it 'redeems' Shylock both from his unbelief and his specific sin of wanting to kill Antonio. This reading of the play would certainly fit with the anti-Semitic trends present in Elizabethan England.

Hyam Maccoby argues that the play is based on medieval morality plays in which the Virgin Mary (here represented by Portia) argues for the forgiveness of human souls, as against the implacable accusations of the Devil (Shylock). On this reading, the Merchant is notably more anti-Semitic than The Jew of Malta, in which there are no good Christian characters and the Jewish villain seems to be regarded by the author with a certain covert sympathy.

The sympathetic reading

Many modern readers and theatregoers have read the play as a plea for tolerance as Shylock is a sympathetic character. Shylock's 'trial' at the end of the play is a mockery of justice, with Portia acting as a judge when she has no real right to do so. Thus, Shakespeare is not calling into question Shylock's intentions, but the fact that the very people who berated Shylock for being dishonest have had to resort to trickery in order to win. Shakespeare puts one of his most eloquent speeches into the mouth of this "villain":

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal'd by the same means, warm'd and cool'd by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

—Act III, scene I

Influence on anti-semitism

Regardless of what Shakespeare's own intentions may have been, the play has been made use of by anti-Semites throughout the play's history. One must note that the end of the title in the 1619 edition "With the Extreme Cruelty of Shylock the Jew…" must aptly describe how Shylock was viewed by the English public. The Nazis used the usurious Shylock for their propaganda. Shortly after Kristallnacht in 1938, "The Merchant of Venice" was broadcast for propagandistic ends over the German airwaves. Productions of the play followed in Lübeck (1938), Berlin (1940), and elsewhere within the Nazi Territory.[12]

The depiction of Jews in English Literature throughout the centuries bears the close imprint of Shylock. With slight variations much of English literature up until the 20th century depicts the Jew as "a monied, cruel, lecherous, avaricious outsider tolerated only because of his golden hoard". [13]

Character study

It is difficult to know whether the sympathetic reading of Shylock is entirely due to changing sensibilities among readers, or whether Shakespeare, a writer who clearly delighted in creating complex, multi-faceted characters, deliberately intended this reading.

One reason for this interpretation is that Shylock's painful status in Venetian society is emphasised. To some critics, Shylock's celebrated "Hath not a Jew eyes" speech (see above) redeems him and even makes him into something of a tragic figure. In the speech, Shylock argues that he is no different from the Christian characters. Detractors note that Shylock ends the speech with a tone of revenge: "if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?" However, those who see the speech as sympathetic point out that Shylock says he learned the desire for revenge from the Christian characters: "If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction."

Even if Shakespeare did not intend the play to be read this way, the fact that it retains its power on stage for audiences who may perceive its central conflicts in radically different terms is an illustration of the subtlety of Shakespeare's characterizations.

A Catholic reading

In 2004 Clare Asquith published her analysis of Shakespeare's writing from the perspective of Catholics toiling under the nascent Reformation movement in England, in her book[14]Shadowplay. Asquith maintains that Shakespeare was a recusant Catholic whose sympathies are covertly woven within his works. Queen Elizabeth I was the third monarch to reign over the Church of England's split from Rome (succeeding her Catholic half-sister Queen Mary who had attempted to undo their younger half-brother Edward's consolidation of Henry VIII's original schism). Asquith's thesis posits that the dramatis personae mask actual persons in the politics of England at the end of the 16th century. Portia can be seen to represent Queen Elizabeth I herself, while Shylock represents a patriarch of the Puritan merchant classes who had suffered under Queen Mary's persecutions. The relevance of the legal setting to the plot calls to mind the conviction that Christ's new Law of Love fulfills the Old Covenant, the natural law revealed to Moses (defended by Shylock in the speech quoted above) whereby an eye-for-an-eye is a reasonable measure, superior to the lawlessness of barbarian rape and pillage, but inferior to peaceful reconciliation dispensed with Christ-like mercy.

The question remains, does Portia dispense a Christian portion of Divine mercy? Or does she deal out a punishment harsher than any that Shylock could have come up with? The final act contains many allusions to Catholic rituals for the celebration of solemnities in the three days before Easter, the Triduum, banned in England at the time the play was published, but still celebrated elsewhere in Catholic Europe, certainly in Venice. As Asquith[14] points out

"The opening love-duet between Lorenzo and Jessica in Act V repeats the phrase "in such a night" eight times: exactly the same number that the phrase "this is the night" is repeated in the great Easter hymn, the Exultet. "

Catholics in England continued to be persecuted for more than two centuries before regaining their religious freedoms, albeit with concessions to the civil rights of their Irish brethren, under the second Catholic Relief Act. Antonio is reprieved by Portia's comprehension of the Christian Mystery: Christ the Pascal Lamb shed blood for us all, justice does not require a second blood-shedding.

Sexuality in the play

Antonio, Bassanio

Antonio's unexplained depression—"In sooth I know not why I am so sad"—and utter devotion to Bassanio has led some critics to theorize that he is suffering from unrequited love for Bassanio and is depressed because Bassanio is coming to an age where he will marry a woman. In his plays and poetry Shakespeare often depicted strong male bonds of varying homosociality, which has led some critics to infer that Bassanio returns Antonio's affections despite his obligation to marry:

- ANTONIO: Commend me to your honourable wife:

- Tell her the process of Antonio's end,

- Say how I lov'd you, speak me fair in death;

- And, when the tale is told, bid her be judge

- Whether Bassanio had not once a love.

- BASSANIO: But life itself, my wife, and all the world

- Are not with me esteemed above thy life;

- I would lose all, ay, sacrifice them all

- Here to this devil, to deliver you. (IV,i)

In his essay "Brothers and Others", published in The Dyer's Hand, W. H. Auden describes Antonio as "a man whose emotional life, though his conduct may be chaste, is concentrated upon a member of his own sex." Antonio's feelings for Bassanio are likened to a couplet from Shakespeare's Sonnets: "But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure,/ Mine be thy love, and my love's use their treasure." Antonio, says Auden, embodies the words on Portia's leaden casket: "Who chooseth me, must give and hazard all he hath." Antonio has taken this potentially fatal turn because he despairs, not only over the loss of Bassanio in marriage, but also because Bassanio cannot requite what Antonio feels for him. Antonio's frustrated devotion is a form of idolatry: the right to live is yielded for the sake of the loved one. There is one other such idolator in the play: Shylock himself. "Shylock, however unintentionally, did, in fact, hazard all for the sake of destroying the enemy he hated; and Antonio, however unthinkingly he signed the bond, hazarded all to secure the happiness of the man he loved." Both Antonio and Shylock, agreeing to put Antonio's life at a forfeit, stand outside the normal bounds of society. There was, states Auden, a traditional "association of sodomy with usury", reaching back at least as far as Dante, with which Shakespeare was likely familiar. (Auden sees the theme of usury in the play as a comment on human relations in a mercantile society.)

Other interpreters of the play regard Auden's conception of Antonio's sexual desire for Bassanio as questionable. Michael Radford, director of the 2004 film version starring Al Pacino, explained that although the film contains a scene where Antonio and Bassanio actually kiss, the friendship between the two is platonic, in line with the prevailing view of male friendship at the time. Jeremy Irons, in an interview, concurs with the director's view and states that he did not "play Antonio as gay".

Bassanio, Portia and fidelity

Portia and Bassanio marry, with the promise that he will never give up her ring. The ring is a symbol of marital fidelity. The Elizabethans were obsessed with wifely fidelity, and a whole subgenre of jokes were devoted to the subject. An Elizabethan audience may have seen the significance of Bassanio giving Portia's "ring" back to her as an emblem of his potential for infidelity.

Adaptations and cultural references

Film adaptations

The Shakespeare play has inspired several films.

- 1914—silent film directed by Lois Weber

- Weber, who also stars as Portia, became the first woman to direct a full-length feature film in America with this film.

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 1973—television film directed by John Sichel

- The cast included Sir Laurence Olivier as Shylock, Anthony Nicholls as Antonio, Jeremy Brett as Bassanio, Joan Plowright as Portia, Louise Purnell as Jessica.

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 1980—A BBC television film directed by Jack Gold

- The cast included Warren Mitchell as Shylock and John Rhys-Davies as Salerio

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 1996—A Channel 4 television film directed by Alan Horrox

- The cast included Paul McGann as Bassanio and Haydn Gwynne as Portia

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 2001—A BBC television film directed by Trevor Nunn

- Royal National Theatre production starring Henry Goodman as Shylock

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 2004—The Merchant of Venice directed by Michael Radford.

- The cast included Al Pacino as Shylock, Jeremy Irons as Antonio, Joseph Fiennes as Bassanio, Lynn Collins as Portia, Zuleikha Robinson as Jessica.

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

Cultural references

Arnold Wesker's play The Merchant tells the same story from Shylock's point of view. In this retelling, Shylock and Antonio are fast friends, and make the bond as a joke against the Christian establishment. Shylock is manipulated into the position of having to enforce it, and is grateful when Portia cuts the knot by showing that the wording is ambiguous and unenforceable.

Edmond Haraucourt, the French playwright and poet, was commissioned in the 1880s by the actor and theatrical director Paul Porel to make a French verse adaptation of the Merchant of Venice. His play Shylock, first performed at the Théâtre de l'Odéon in December 1889, had incidental music by the French composer Gabriel Fauré, later incorporated into an orchestral suite of the same name.[15]

One of the four short stories comprising Alan Isler's Op Non Cit is also told from Shylock's point of view. In this story, Antonio was a boy of Jewish origin kidnapped at an early age by priests...

Roman Polanski's movie The Pianist contains the quote "If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die?" As pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman and others are waiting for the trains, Szpilman sees his brother reading from "The Merchant of Venice." He asks the man to read aloud, after which Szpilman comments that it is an appropriate play for their situation. His brother responds, "That's why I brought it."

Stephenie Meyer's Breaking Dawn mentions "The Merchant of Venice" as the means for the character Alice to give a message to the heroine Bella and the rest of the Cullen family, by ripping out the copyright page to write a note for the family, as well as inscribing a message only meant for Bella to know on the remaining book. Meyer has also said that Breaking Dawn was based on "The Merchant of Venice" as well as "A Midsummer's Night Dream".

In the movie Se7en, one of the victims of John Doe is forced to cut a pound of flesh from his body.

In The Naked Now, an episode of the television series Star Trek: The Next Generation, Data at one point says "If you prick us do we not... leak?"

Pastime

- The device of three caskets with riddles has been used for logic puzzles in works like What is the name of this book? by Raymond Smullyan. The coffers make assertions about the truthfulness of their and the other inscriptions (e.g. the golden casket has the portrait, two of the caskets are lying"), to discover the portrait of Portia, and the reader of the pastime has to find which is telling truth.

Notes

- ↑ Caldecott: Our English Homer, p. 9.

- ↑ Stanley Wells and Michael Dobson, eds., The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 288.

- ↑ Charles Boyce, Encyclopaedia of Shakespeare, New York, Roundtable Press, 1990, p. 420.

- ↑ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 261, 311–12.

- ↑ Adler erroneously dates this from 1847 (at which time Kean was already dead); the Cambridge Student Guide to The Merchant of Venice dates Kean's performance to a more likely 1814.

- ↑ Adler 1999, 341.

- ↑ Wells and Dobson, p. 290.

- ↑ Adler 1999, 342–44.

- ↑ Adler 1999, 344–350

- ↑ Philipe Burrin, Nazi Anti-Semitism: From Prejudice to Holocaust. The New Press, 2005, ISBN 1-56584-969-8, p. 17.

It was not until the twelfth century that in northern Europe (England, Germany, and France), a region until then peripheral but at this point expanding fast, a form of Judeophobia developed that was considerably more violent because of a new dimension of imagined behaviors, including accusations that Jews engaged in ritual murder, profanation of the host, and the poisoning of wells. With the preduces of the day against Jews, atheists and non christians in general Jews found it hard to fit in with society. Some say that these attitudes provided the foundations of anti-semitism in the 20th century. "

- ↑ The Virtual Jewish History Tour - Venice

- ↑ Lecture by James Shapiro: "Shakespeare and the Jews"

- ↑ The Fictive Jew in the Literature of England 1890-1920 David Mirsky in the Samuel K. Mirsky Memorial Volume.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 ASQUITH, Clare, Shakespeare’s Catholic Code.

- ↑ Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991), Gabriel Fauré: A musical life, Cambridge University Press, pp. 143-146, ISBN 0-521-23524-3

References

- Adler, Jacob, A Life on the Stage: A Memoir, translated and with commentary by Lulla Rosenfeld, Knopf, New York, 1999, ISBN 0-679-41351-0.

- Caldecott, Henry Stratford: Our English Homer; or, the Bacon-Shakespeare Controversy (Johannesburg Times, 1895).

- Smith, Rob: Cambridge Student Guide to The Merchant of Venice. ISBN 0-521-00816-6.

- Yaffe, Martin D.: Shylock and the Jewish question.

External links

- The Merchant of Venice Navigator — annotated, searchable text.

- The Merchant of Venice — plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

- The Merchant of Venice — HTML version of this title.

- The Merchant of Venice — Searchable version of the play, indexed by scene.

- Thesis statements & important quotes from The Merchant of Venice

- CliffsNotes

- SparkNotes: Study Guide

- Filmschatten — film The Merchant of Venice (1910) online

- Lesson plans for The Merchant of Venice at Web English Teacher

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||