Tetrapod

| Tetrapods Fossil range: 365–0 Ma Late Devonian to Recent |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Fire Salamander.

|

||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Clades | ||||||||

|

Amphibia |

Tetrapods (Greek τετραποδη tetrapoda, Latin quadruped, "four-footed") are vertebrate animals having four feet, legs or leglike appendages. Amphibians, reptiles, dinosaurs/birds, and mammals are all tetrapods, and even the limbless snakes are tetrapods by descent. The earliest tetrapods radiated from the Sarcopterygii, or lobe-finned fish, into air-breathing amphibians in the Devonian period.

Contents |

Evolution

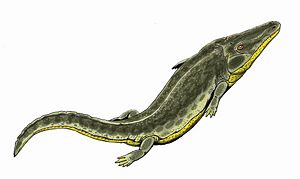

•Panderichthys, suited to muddy shallows;

•Tiktaalik with limb-like fins that could take it onto land;

•Early tetrapods in weed-filled swamps, such as;

•Acanthostega, which had feet with eight digits,

•Ichthyostega with limbs.

Descendants also included pelagic lobe-finned fish such as coelacanth species.

Devonian tetrapods

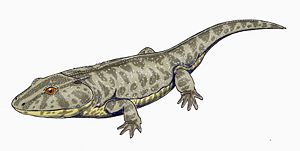

Research by Jennifer A. Clack and her colleagues showed that the earliest tetrapods, such as Acanthostega, were wholly aquatic and quite unsuited to life on land. This overturned the earlier view that fish had first invaded the land — either in search of prey (like modern mudskippers) or to find water when the pond they lived in dried out — and later evolved legs, lungs, etc.

The first tetrapods are now thought to have evolved in shallow and swampy freshwater habitats, towards the end of the Devonian, a little more than 365 million years ago. By the late Devonian, land plants had stabilized freshwater habitats, allowing the first wetland ecosystems to develop, with increasingly complex food webs that afforded new opportunities. [1] Freshwater habitats were not the only places to find water filled with organic matter and choked with plants with dense vegetation near the water's edge. Swampy habitats like shallow wetlands, coastal lagoons and large brackish river deltas also existed at this time, and there is much to suggest that this is the kind of environment in which the tetrapods evolved. Early fossil tetrapods have been found in marine sediments, and because fossils of primitive tetrapods in general are found scattered all around the world, they must have spread by following the coastal lines — they could not have lived in freshwater only.

The common ancestor of all present gnathostomes lived in freshwater, and later migrated back to the sea. To deal with the much higher salinity in sea water, they evolved the ability to turn the nitrogen waste product ammonia into harmless urea, storing it in the body to make the blood as salty as the sea water without poisoning the organism. Ray-finned fishes later returned to freshwater and lost this ability. Since their blood contained more salt than freshwater, they could simply get rid of ammonia through their gills. When they finally returned to the sea again, they could not recover their old trick of turning ammonia to urea, and they had to evolve salt excreting glands instead. Lungfishes do the same when they are living in water, making ammonia and no urea, but when the water dries up and they are forced to burrow down in the mud, they switch to urea production. Like cartilaginous fishes, the coelacanth can store urea in its blood, as can the only known amphibians that can live for long periods of time in salt water (the toad Bufo marinus and the frog Rana cancrivora). These are traits they have inherited from their ancestors.

If early tetrapods lived in freshwater, and if they lost the ability to produce urea and used ammonia only, they would have to evolve it from scratch again later. Not a single species of all the ray-finned fishes living today has been able to do that, so it is not likely the tetrapods would have done so either. Terrestrial animals that can only produce ammonia would have to drink constantly, making a life on land impossible (a few exceptions exist, as some terrestrial woodlice can excrete their nitrogenous waste as ammonia gas). This probably also was a problem at the start when the tetrapods started to spend time out of water, but eventually the urea system would dominate completely. Because of this it is not likely they emerged in freshwater (unless they first migrated into freshwater habitats and then migrated onto land so shortly after that they still retained the ability to make urea), although some species never left, or returned to, the water could of course have adapted to freshwater lakes and rivers.

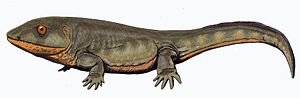

Primitive tetrapods developed from a lobe-finned fish (an "osteolepid sarcopterygian"), with a two-lobed brain in a flattened skull, a wide mouth and a short snout, whose upward-facing eyes show that it was a bottom-dweller, and which had already developed adaptations of fins with fleshy bases and bones (the "living fossil" coelacanth is a related marine lobe-finned fish without these shallow-water adaptations).

Even more closely related was Panderichthys, which even had a choana. These fishes used their fins as paddles in shallow-water habitats choked with plants and detritus. Their fins could also have been used to attach themselves to plants or similar while they were laying in ambush for prey. The universal tetrapod characteristics of front limbs that bend backward at the elbow and hind limbs that bend forward at the knee can plausibly be traced to early tetrapods living in shallow water.

It is now clear that the common ancestor of the bony fishes had a primitive air-breathing lung (later evolved into a swim bladder in most ray-finned fishes). This suggests that it evolved in warm shallow waters, the kind of habitat the lobe finned fishes were living and made use of their simple lung when the oxygen level in the water became too low.

The lungfishes are now considered as being the closest living relatives of the tetrapods, even closer than the coelacanth.

Fleshy lobe fins supported on bones rather than ray-stiffened fins seems to have been an original trait of the bony fishes (Osteichthyes). The lobe-finned ancestors of the tetrapods evolved them further, while the ancestors of the ray-finned (Actinopterygii) fishes evolved their fins in the opposite direction. The most primitive group of the ray-fins, the bichirs, still have fleshy frontal fins.

Nine genera of Devonian tetrapods have been described, several known mainly or entirely from lower jaw material. All of them were from the European-North American supercontinent, which comprised Europe, North America and Greenland. The only exception is a single Gondwanan genus, Metaxygnathus, which has been found in Australia.

The first Devonian tetrapod identified from Asia was recognized from a fossil jawbone reported in 2002. The Chinese tetrapod Sinostega pani was discovered among fossilized tropical plants and lobe-finned fish in the red sandstone sediments of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of northwest China. This finding substantially extended the geographical range of these animals and has raised new questions about the worldwide distribution and great taxonomic diversity they achieved within a relatively short time.

These earliest tetrapods were not terrestrial. The earliest confirmed terrestrial forms are known from the early Carboniferous deposits, some 20 million years later. Still, they may have spent very brief periods out of water and would have used their legs to paw their way through the mud.

Why they went to land in the first place is still debated. One reason could be that the small juveniles who had completed their metamorphosis had what it took to make use of what land had to offer. Already adapted to breathe air and move around in shallow waters near land as a protection (just as modern fish (and amphibians) often spent the first part of their life in the comparative safety of shallow waters like mangrove forests), two very different niches partially overlapped each other, with the young juveniles in the diffuse line between. One of them was overcrowded and dangerous while the other was much safer and much less crowded, offering less competition over resources. The terrestrial niche was also a much more challenging place for primary aquatic animals, but because of the way evolution and the selection pressure works, those juveniles who could take advantage of this would be rewarded. Once they gained a small foothold on land, thanks to their preadaptations and being at the right place at the right time, favourable variations in their descendants would gradually result in continuing evolution and diversification.

At this time the abundance of invertebrates crawling around on land and near water, in moist soil and wet litter, offered a food supply. Some were even big enough to eat small tetrapods, but the land was free from dangers common in the water.

It is plausible that at first adults would be too heavy and slow and have greater needs for large prey. Small juveniles would be much lighter, faster and could subsist on relatively small invertebrates. Modern mudskippers are said to be able to snap insects in flight while on land, and the early juvenile tetrapods might also have shown formidable ablilities.

Initially making only tentative forays onto land, as the generations went by they adapted to terrestrial environments and spent longer periods away from the water, also spending a longer part of their childhood on land before returning to the water for the rest of their life. It is possible also the adults started to spend some time on land as the skeletal modifications in early tetrapods as Ichthyostega suggests, but only to bask in the sun close to the water's edge, not to hunt or move around. It is a fact that the first true tetrapods adapted to terrestrial locomotion were small. Only later did they increase in size.

The fully grown obviously kept most of the anatomical and other forms of adaptations from their juvenile stage, giving them modified limbs and other traits of terrestrial properties. To be successful adults they first had to be successful juveniles. The adults of some of the smaller species were in that case probably able to move on land too when sufficiently evolved.

If some sort of neoteny or dwarfism occurred, making the animals sexually mature and fully grown while still living on land, they would only need to visit water to drink and reproduce.

Carboniferous tetrapods

Until the 1990s, there was a 30 million year gap in the fossil record between the late Devonian tetrapods and the reappearance of tetrapod fossils in recognizable mid-Carboniferous amphibian lineages. It was referred to as "Romer's Gap", after the palaeontologist who recognized it.

During the "gap", tetrapod backbones developed, as did limbs with digits and other adaptations for terrestrial life. Ears, skulls and vertebral columns all underwent changes too. The number of digits on hands and feet became standardized at five, as lineages with more digits died out. The very few tetrapod fossils found in the "gap" are all the more precious.

The transition from an aquatic lobe-finned fish to an air-breathing amphibian was a momentous occasion in the evolutionary history of the vertebrates. For an animal to live in a gravity-neutral, aqueous environment and then invade one that is entirely different required major changes to the overall body plan, both in form and in function. Eryops is an example of an animal that made such adaptations. It retained and refined most of the traits found in its fish ancestors. Sturdy limbs supported and transported its body while out of water. A thicker, stronger backbone prevented its body from sagging under its own weight. Also, by utilizing vestigial fish jaw bones, a rudimentary ear was developed, allowing Eryops to hear airborne sound.

By the Visean age of mid-Carboniferous times the early tetrapods had radiated into at least three main branches. Recognizable basal-group tetrapods are representative of the temnospondyls (e.g. Eryops) and similarly primitive anthracosaurs, which were the relatives and ancestors of the Amniota. Depending on whichever authorities one follows, modern amphibians (frogs, salamanders and caecilians) are derived from one or the other (or possibly both, although this is now a minority position) of these two groups. The first amniotes are known from the early part of the Late Carboniferous, and during the Triassic counted among their number the earliest mammals, turtles, and crocodiles (lizards and birds appeared in the Jurassic, and snakes in the Cretaceous). As living members of the tetrapod clan — that is of the tetrapod "crown-group" — these varied tetrapods represent the phylogenetic end-points of these two divergent lineages. A third, more primitive, Carboniferous group, the baphetids, left no modern survivors. Finally, the Lepospondyli are an extinct Palaeozoic group of uncertain relationships.

Permian tetrapods

In the Permian period, as the separate tetrapod lineages each developed in their own way, the term "tetrapoda" becomes less useful. In addition to temnospondyl and anthracosaur clades among the early "amphibia" (labyrinthodonts), there were two important divergent clades of amniotes, the Sauropsida and the Synapsida, of which the latter were the most important and successful Permian animals. Each of these lineages, however, remains grouped with the tetrapoda, just as Homo sapiens could be considered a very highly-specialized kind of lobe-finned fish.

Living tetrapods

There are three main categories of living ("crown group") tetrapods, all of which also include many extinct groups:

- Amphibia

- frogs and toads, newts and salamanders, and caecilians

- Sauropsida

- birds and modern reptiles

- Synapsida

- mammals

Note that snakes and other legless reptiles are considered tetrapods because they are descended from ancestors who had a full complement of limbs. Similar considerations apply to caecilians and aquatic mammals.

Classification

All early tetrapods and tetrapodomorphs that were not true amphibians or amniotes were once placed together in the paraphyletic group Labyrinthodontia. Labyrinthodonts were distinguished mainly by their complex dentine infolding tooth structure, a feature shared with crossopterygian fish. The labyrinthodonts were divided into the Ichthyostegalia (another paraphyletic assemblage of primitive tetrapods and kin, such as Ichthyostega), the Temnospondyli (possibly members of Amphibia), and the Anthracosauria (close relatives of amniotes). The main difference between the three groups was based on their respective vertebral structures. The Anthracosauria had small pleurocentra, which grew and fused, becoming the true centrum in later vertebrates. In contrast, the Temnospondyli had a conservative vertebral column in which the pleurocentra remained small in primitive forms, vanishing entirely in the more advanced ones. The intercentra are large and form a complete ring.

Although the temnospondyls flourished in many forms in the Late Paleozoic and Triassic, they were an entirely self-contained group and did not give rise to any later tetrapod groups. It was the sister group Anthracosauria that gave rise to the reptiles.

Tetrapod groups

A partial taxonomy of the tetrapods:

- Phylum Chordata

-

- Class Sarcopterygii

- Subclass Tetrapodomorpha

- Eusthenopteron

- Panderichthys

- Tiktaalik

- Ventastega

- Subclass Tetrapodomorpha

- Class Sarcopterygii

- Superclass Tetrapoda

-

-

- Family Elginerpetontidae

- Family Acanthostegidae

- Family Ichthyostegidae

- Hynerpeton

- Family Whatcheeriidae

- Family Crassigyrinidae

- Family Loxommatidae

- Family Colosteidae

- Batrachomorpha

-

- Class Amphibia — Amphibians

- Subclass Lepospondyli

- Subclass Temnospondyli

- Subclass Lissamphibia — frogs, salamanders

- Superorder Reptiliomorpha

- Amniota

- Class Sauropsida — Reptiles

- Class Aves — Birds

- Class Synapsida — Mammal-like reptiles

- Class Mammalia — Mammals

-

-

Anatomical features of early tetrapods

The tetrapod's ancestral fish must have possessed similar traits to those inherited by the early tetrapods, including internal nostrils (to separate the breathing and feeding passages) and a large fleshy fin built on bones that could give rise to the tetrapod limb. The rhipidistian crossopterygians fulfill every requirement for this ancestry. Their palatal and jaw structures were identical to those of early tetrapods, and their dentition was identical too, with labyrinthine teeth fitting in a pit-and-tooth arrangement on the palate. The crossopterygian paired fins were smaller than tetrapod limbs, but the skeletal structure was very similar in that the crossopterygian had a single proximal bone (analogous to the humerus or femur), two bones in the next segment (forearm or lower leg), and an irregular subdivision of the fin, roughly comparable to the structure of the carpus / tarsus and phalanges of a hand.

The major difference between crossopterygians and early tetrapods was in relative development of front and back skull portions; the snout is much less developed than in most early tetrapods and the post-orbital skull is exceptionally longer than an amphibian's.

A great many kinds of early tetrapods lived during the Carboniferous period. Therefore, their ancestor would have lived earlier, during the Devonian period. Devonian Ichthyostegids were the earliest of true tetrapods, with a skeleton that is directly comparable to that of rhipidistian ancestors. Early temnospondyls (Late Devonian to Early Mississippian) still had some ichthyostegid features such as similar skull bone patterns, labyrinthine tooth structure, the fish skull-hinge, pieces of gill structure between the cheek and shoulder, and the vertebral column. They had, however, lost several other fish features such as the fin rays in the tail.

In order to propagate in the terrestrial environment, certain challenges had to be overcome. The animal's body needed additional support, because buoyancy was no longer a factor. A new method of respiration was required in order to extract atmospheric oxygen, instead of oxygen dissolved in water. A means of locomotion would need to be developed to traverse distances between waterholes. Water retention was now important since it was no longer the living matrix, and it could be lost easily to the environment. Finally, new sensory input systems were required if the animal was to have any ability to function reasonably while on land.

Skull

The most notable characteristics that make a tetrapod skull different from a fish's are the relative frontal and rear portion lengths. The fish had a long rear portion while the front was short; the orbital vacuities were thus located towards the anterior end. In the tetrapod, the front of the skull lengthened, positioning the orbits farther back on the skull. The lacrimal bone was not in contact with the frontal anymore, having been separated from it by the prefrontal bone. Also of importance is that the skull was now free to rotate from side to side, independent of the spine, on the newly forming neck.

A diagnostic character of temnospondyls is that the tabular bones (which formed the posterior corners of the skull-table) were separated from the respective left and right parietals by a sutural junction between the postparietals and supratemporals. Also at the rear of the skull, all bones dorsal to the cleithrum were lost.

The lower jaw of, for example, Eryops resembled its crossopterygian ancestors in that on the outer surface lay a long dentary that bore teeth. There were also bones below the dentary on the jaw: two splenials, the angulary and the surangular. On the inside were usually three coronoids that bore teeth and lay close to the dentary. On the upper jaw was a row of marginal labyrinthine teeth, located on the maxilla and premaxilla. In Eryops, as in all early amphibians, the teeth were replaced in waves that traveled from the front of the jaw to the back in such a way that every other tooth was mature, and the ones in between were young.

Dentition

The "labyrinthodonts" had a peculiar tooth structure from which their name was derived and, although not exclusive to the group, the labyrinthine dentition is a useful indicator as to proper classification. The important feature of the tooth is that the enamel and dentine were folded in such a way as to form a complicated corrugated pattern when viewed in cross section. This infolding resulted in strengthening of the tooth and increased wear resistance. Such teeth survived for 100 Ma, first among crossopterygian fish, then stem reptiles. Modern amphibians no longer have this type of dentition but rather pleurodont teeth, in fewer numbers of the whole group.

Sensory organs

There is a density difference between air and water that causes smells (certain chemical compounds detectable by chemoreceptors) to behave differently. An animal first venturing out onto land would have difficulty in locating such chemical signals if its sensory apparatus was designed for aquatic detection.

Fish have a lateral line system that detects pressure fluctuations in the water. Such pressure is non-detectable in air, but grooves for the lateral line sense organs were found on the skull of labyrinthodonts, suggesting a partially aquatic habitat. Modern amphibians, which are semi-aquatic, exhibit this feature whereas it has been retired by the higher vertebrates. The olfactory epithelium would also have to be modified in order to detect airborne odors.

In addition to the lateral line organ system, the eye had to change as well. This change came about because the refractive index of light differs between air and water, so the focal length of the lens was altered in order to properly function. The eye was now exposed to a relatively dry environment rather than being bathed by water, so eyelids developed and tear ducts evolved to produce a liquid, moistening the eyeball.

Hearing

The balancing function of the middle ear was retained from the fish ancestry, but delicate air vibrations could not set up pulsations through the skull in order for it to function a proper auditory organ. Typical of most labyrinthodonts, the spiracular gill pouch was retained as the otic notch, closed in by the tympanum, a thin, tight membrane.

The hyomandibula of fish migrated upwards from its jaw supporting position, and was reduced in size to form the stapes. Situated between the tympanum and braincase in an air-filled cavity, the stapes was now capable of transmitting vibrations from the exterior of the head to the interior. Thus the stapes became an important element in an impedance matching system, coupling airborne sound waves to the receptor system of the inner ear. This system had evolved independently within several different amphibian lineages.

In order for the impedance matching ear to work, certain conditions had to be met. The stapes must have been perpendicular to the tympanum, small and light enough to reduce its inertia and suspended in an air-filled cavity. In modern species that are sensitive to over 1 kHz frequencies, the footplate of the stapes is 1/20th the area of the tympanum. However, in early amphibians the stapes was too large, making the footplate area oversized, preventing the hearing of high frequencies. So it appears that only high intensity, low frequency sounds could be detected, with the stapes more probably being used to support the braincase against the cheek.

"Did Our Ancestors Breathe through Their Ears?"

Girdles

The pectoral girdle of early tetrapods such as Eryops was highly developed, with a larger size for both increased muscle attachment to it and to the limbs. Most notably, the shoulder girdle was disconnected from the skull, resulting in improved terrestrial locomotion. The crossopterygian cleithrum was retained as the clavicle, and the interclavicle was well-developed, lying on the underside of the chest. In primitive forms, the two clavicles and the interclavical could have grown ventrally in such a way as to form a broad chest plate, although such was not the case in Eryops. The upper portion of the girdle had a flat, scapular blade, with the glenoid cavity situated below performing as the articulation surface for the humerus, while ventrally there was a large, flat coracoid plate turning in toward the midline.

The pelvic girdle also was much larger than the simple plate found in fishes, accommodating more muscles. It extended far dorsally and was joined to the backbone by one or more specialized sacral ribs. The hind legs were somewhat specialized in that they not only supported weight, but also provided propulsion. The dorsal extension of the pelvis was the ilium, while the broad ventral plate was comprised of the pubis in front and the ischium in behind. The three bones met at a single point in the center of the pelvic triangle called the acetabulum, providing a surface of articulation for the femur.

The main strength of the ilio-sacral attachment of Eryops was by ligaments, a condition structurally, but not phylogenetically, intermediate between that of the most primitive embolomerous amphibians and early reptiles. The condition that is more usually found in higher vertebrates is that cartilage and fusion of the sacral ribs to the blade of the ilium are utilized in addition to ligamentous attachments.

Limbs

The humerus was the largest bone of the arm, its head articulating with the glenoid cavity of the pectoral girdle, distally with the radius and ulna. The radius resided on the inner side of the forearm and rested directly under the humerus, supporting much of the weight, while the ulna was located to the outside of the humerus. The ulna had a head, which muscles pulled on to extend the limb, called the olecranon that extended above the edge of the humerus.

The radius and the ulna articulated with the carpus, which was a proximal row of three elements: the radiale underlying the radius, the ulnare underneath the ulna and an intermedium between the two. A large central element was beneath the last and may have articulated with the radius. There were also three smaller centralia lying to the radial side. Opposite the head of each toe lay a series of five distal carpals. Each digit had a first segment, the metacarpal, lying in the palm region.

The pelvic limb bones were essentially the same as in the pectoral limb, but with different names. The analogue to the humerus was the femur, which was longer and slimmer. The two lower arm bones corresponded to the tibia and fibula of the hind leg, the former being the innermost and the latter the outermost bones. The tarsus is the hind version of the carpus and its bones correspond as well.

Feeding

Early tetrapods had a wide gaping jaw with weak muscles to open and close it. In the jaw were fang-like palatal teeth that, when coupled with the gape, suggests an inertial feeding habit. This is when the amphibian would grasp the prey and, lacking any chewing mechanism, toss the head up and backwards, throwing the prey farther back into the mouth. Such feeding is seen today in the crocodile and alligator.

The tongue of modern adult amphibians is quite fleshy and attached to the front of the lower jaw, so it is reasonable to speculate that it was fastened in a similar fashion in primitive forms, although it was probably not specialized like it is in a frog.

It is taken that early tetrapods were not very active, thus a predatory lifestyle was probably not the norm. It is more likely that it fed on fish either in the water or on those that became stranded at the margins of lakes and swamps. Also abundant at the time was a large supply of terrestrial invertebrates, which may have provided a fairly adequate food supply.

Respiration

Modern amphibians breathe by inhaling air into lungs, where oxygen is absorbed. They also breathe through the moist lining of the mouth and skin. Eryops also inhaled, but its ribs were too closely spaced to suggest that it did this by expanding the rib cage. More likely, it opened its mouth and nostrils, depressed the hyoid apparatus to expand the oral cavity, closed its mouth and nostrils finally and elevated the floor of the mouth to force air back into the lungs — in other words, it gulped then swallowed. It probably exhaled by contraction of the elastic tissue in the lung walls. Other special respiratory methods probably existed.

Circulation

Early tetrapods most likely had a three-chambered heart, as do modern amphibians and reptiles, in which oxygenated blood from the lungs and de-oxygenated blood from the respiring tissues enters by separate atria, and is directed via a spiral valve to the appropriate vessel — aorta for oxygenated blood and pulmonary vein for deoxygenated blood. The spiral valve is essential to keeping the mixing of the two types of blood to a minimum, enabling the animal to have higher metabolic rates, and be more active than otherwise.

Locomotion

In typical early tetrapod posture the upper arm and upper leg extended nearly straight horizontal from its body, and the forearm and the lower leg extended downward from the upper segment at a near right angle. The body weight was not centered over the limbs, but was rather transferred 90 degrees outward and down through the lower limbs, which touched the ground. Most of the animal's strength was used to just lift its body off the ground for walking, which was probably slow and difficult. With this sort of posture, it could only make short broad strides. This has been confirmed by fossilized footprints found in Carboniferous rocks.

Ligamentous attachments within the limbs were present in Eryops, being important because they were the precursor to bony and cartilaginous variations seen in modern terrestrial animals that use their limbs for locomotion.

Of all body parts, the spine was the most affected by the move from water to land. It now had to resist the bending caused by body weight and had to provide mobility where needed. Previously, it could bend along its entire length. Likewise, the paired appendages had not been formerly connected to the spine, but the slowly strengthening limbs now transmitted their support to the axis of the body.

References

See also

- Geologic timescale

- Prehistoric life

- Body form

External links

- Tree of Life: Terrestrial Vertebrates

- "Tetrapod"? What is a tetrapod?

- UCMP Taxonomy page

- Tetrapod cladograms — similar to genealogical family trees

- How did fish grow legs?

- New fossils fill gap between water and land animals

- Human Ears Evolved from Ancient Fish Gills

- Scientific American: Getting a Leg Up on Land

Devonian tetrapods

- Sinostegia discovery reported in National Geographic

- Devonian Times

- Devonian Times — Tetrapod Trackways

- Scientists find 245 million-year-old burrows of land vertebrates in Antarctica

Carboniferous tetrapods

- Detailed account of early tetrapod evolution — This website, geared to the layman, also describes Jennifer Clack's role in untangling the early evolution of tetrapods.

- Abstract of Jennifer A. Clack, "An early tetrapod from 'Romer's Gap'" in Nature, July 2002

- Abstract of Jennifer Clack's identification of a primitive baphetid tetrapod

- "The evolution of tetrapods and the closing of Romer's Gap."