Tensor

| Disambiguation |

|

A tensor is an object which extends the notion of scalar, vector, and matrix. The term has slightly different meanings in mathematics and physics. In the mathematical fields of multilinear algebra and differential geometry, a tensor is a multilinear function. In physics and engineering, the same term usually means what a mathematician would call a tensor field: an association of a different (mathematical) tensor with each point of a geometric space, varying continuously with position.

Contents |

History

The word tensor was introduced in 1846 by William Rowan Hamilton[1] to describe the norm operation in a certain type of algebraic system (eventually known as a Clifford algebra). The word was used in its current meaning by Woldemar Voigt in 1898.[2]

Tensor calculus was developed around 1890 by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro under the title absolute differential calculus, and was made accessible to many mathematicians by the publication of Tullio Levi-Civita's 1900 classic text of the same name (in Italian; translations followed). In the 20th century, the subject came to be known as tensor analysis, and achieved broader acceptance with the introduction of Einstein's theory of general relativity, around 1915.

General relativity is formulated completely in the language of tensors. Einstein had learned about them, with great difficulty, from the geometer Marcel Grossmann,[3] or perhaps from Levi-Civita himself. Tensors are used also in other fields such as continuum mechanics.

Two usages of 'tensor'

Mathematical

In mathematics, a tensor is (in an informal sense) a generalized linear 'quantity' or 'geometrical entity' that can be expressed as a multi-dimensional array relative to a choice of basis of the particular space on which it is defined. The intuition underlying the tensor concept is inherently geometrical: as an object in and of itself, a tensor is independent of any chosen frame of reference. However, in the modern treatment, tensor theory is best regarded as a topic in multilinear algebra. Engineering applications do not usually require the full, general theory, but theoretical physics now does.

For example, the Euclidean inner product (dot product)—a real-valued function of two vectors that is linear in each—is a mathematical tensor. Similarly, on a smooth curved surface such as a torus, the metric tensor (field) essentially defines a different inner product of tangent vectors at each point of the surface. Just as a linear transformation can be represented as a matrix of numbers with respect to given vector bases, so a tensor can be written as an organized collection of numbers. In physics, the numbers may be obtained as physical quantities that depend on a basis, and the collection is determined to be a tensor if the quantities transform appropriately under change of basis.

Physical tensor fields

Many mathematical structures informally called 'tensors' are actually tensor fields—a tensor-valued function defined on a geometric or topological space. This use of the term is analogous to vector fields such as electromagnetic fields, but with the 'tensor' defined so that it is invariant under a change of coordinates. Differential equations posed in terms of tensor quantities are basic to modern mathematical physics, so that tensor fields are usually defined on differentiable manifolds.

Tensor rank

In mathematics, the term rank of a tensor may mean either of two things, and it is not always clear from the context which.

In the first definition, the rank of a tensor T is the number of indices required to write down the components of T. Under this definition a scalar is a tensor of rank 0, a vector is a tensor of rank 1, and a matrix is a tensor of rank 2. This is the sum of the number of covariant and contravariant indices. Expressed by means of the tensor product of multilinear algebra, this is the number of factors of the tensor product needed to express T.

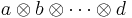

In the second definition, the rank of a tensor is defined in a way that extends the definition of the rank of a matrix given in linear algebra. A tensor of rank 1 (also called a simple tensor) is a tensor that can be written as a tensor product of the form

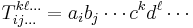

where a, b,...,d are in V or V*. In indices, a tensor of rank 1 is a tensor of the form

Every tensor can be expressed as a linear combination of rank 1 tensors. In general, the rank of T is the minimum number of rank 1 tensors with which it is possible to express T as a linear combination.

For example, a matrix is a tensor with 2 indices, and so has rank 2 in the first definition. On the other hand, the rank of the tensor in the second definition is just the rank of the matrix. This latter meaning is possibly the intended one, whenever the array of components is two-dimensional.

To avoid this ambiguity, it is now preferred to use the terminology of tensor order to denote the number of indices, and tensor rank to designate the number of simple tensors necessary to decompose a tensor. Hence the definition of rank is now used in a way that is consistent with Linear Algebra.

Tensor valence

In physical applications, array indices are distinguished by being contravariant (superscripts) or covariant (subscripts), depending upon the type of transformation properties. The valence of a particular tensor is the number and type of array indices; tensors with the same tensor order but different valence are not, in general, identical. However, any given covariant index can be transformed into a contravariant one, and vice versa, by applying the metric tensor. This operation is generally known as raising or lowering indices.

Importance and applications

Tensors are important in physics and engineering. In the field of diffusion tensor imaging, for instance, a tensor quantity that expresses the differential permeability of organs to water in varying directions is used to produce scans of the brain; in this technique tensors are in effect made visible. Perhaps the most important engineering examples are the stress tensor and strain tensor, which are both 2nd rank tensors, and are related in a general linear elastic material by a fourth-rank elasticity tensor.

Specifically, a 2nd rank tensor quantifying stress in a 3-dimensional/solid object has components which can be conveniently represented as a 3x3 array. The three Cartesian faces of a cube-shaped infinitesimal volume segment of the solid are each subject to some given force. The force's vector components are also three in number (being in three-space). Thus, 3x3, or 9 components are required to describe the stress at this cube-shaped infinitesimal segment (which may now be treated as a point). Within the bounds of this solid is a whole mass of varying stress quantities, each requiring 9 quantities to describe. Thus, the need for a 2nd order tensor is produced.

While tensors can be represented by multi-dimensional arrays of components, the point of having a tensor theory is to explain further implications of saying that a quantity is a tensor, beyond specifying that it requires a number of indexed components. In particular, tensors behave in specific ways under coordinate transformations. The abstract theory of tensors is a branch of linear algebra, now called multilinear algebra.

The choice of approach

There are two ways of approaching the definition of tensors:

- The usual physics way of defining tensors, in terms of objects whose components transform according to certain rules, introducing the ideas of covariant or contravariant transformations.

- The usual mathematics way, which involves defining certain vector spaces and not fixing any coordinate systems until bases are introduced when needed. Contravariant vectors, for instance, can also be described as one-forms, or as the elements of the dual space to the covariant vectors.

Physicists and engineers are among the first to recognise that vectors and tensors have a physical significance as entities, which goes beyond the (often arbitrary) coordinate system in which their components are enumerated. Similarly, mathematicians find there are some tensor relations which are more conveniently derived in a coordinate notation.

Examples

Physical examples

As a simple example, consider a ship in the water. We want to describe its response to an applied force. Force is a vector, and the ship will respond with an acceleration, which is also a vector. The relationship between force and acceleration is linear in classical mechanics. Such a relationship is described by a rank two tensor of type (1,1) (that is to say, here it transforms a plane vector into another such vector). The tensor can be represented as a matrix which when multiplied by a vector results in another vector. Just as the numbers which represent a vector will change if one changes the coordinate system, the numbers in the matrix that represents the tensor will also change when the coordinate system is changed.

In engineering, the stresses inside a solid body or fluid are also described by a tensor; the word "tensor" is Latin for something that stretches, i.e., causes tension. If a particular surface element inside the material is singled out, the material on one side of the surface will apply a force on the other side. In general, this force will not be orthogonal to the surface, but it will depend on the orientation of the surface in a linear manner. This is described by a tensor of type (2,0), in linear elasticity, or more precisely by a tensor field of type (2,0) since the stresses may change from point to point.

Mathematical examples

Some well-known examples of tensors in differential geometry are quadratic forms, such as metric tensors, and the curvature tensor.

Formally speaking, a tensor has a particular type according to the construction with tensor products that give rise to it. For computational purposes, it may be expressed as the sequence of values represented by a function with a tuple-valued domain and a scalar valued range. Domain values are tuples of counting numbers, and these numbers are called indices. For example, a rank 3 tensor might have dimensions 2, 5, and 7. Here, the indices range from «1, 1, 1» through «2, 5, 7»; thus the tensor would have one value at «1, 1, 1», another at «1, 1, 2», and so on for a total of 70 values. As a special case, (finite-dimensional) vectors may be expressed as a sequence of values represented by a function with a scalar valued domain and a scalar valued range; the number of distinct indices is the dimension of the vector. Using this approach, the rank 3 tensor of dimension (2,5,7) can be represented as a 3-dimensional array of size 2 × 5 × 7. In this usage, the number of "dimensions" comprising the array is equivalent to the "rank" of the tensor, and the dimensions of the tensor are equivalent to the "size" of each array dimension.

A tensor field associates a tensor value with every point on a manifold. Thus, instead of simply having 70 values as indicated in the above example, for a rank 3 tensor field with dimensions «2, 5, 7»; every point in the space would have 70 values associated with it. In other words, a tensor field means there's some tensor-valued function which has, for example, Euclidean space as its domain.

Approaches, in detail

There are equivalent approaches to visualizing and working with tensors; that the content is actually the same may only become apparent with some familiarity with the material.

- The classical approach

- The classical approach defines a tensor to a collection of multidimensional arrays, such that one array is associated to each possible coordinate system of any fixed vector space. This notion generalizes scalars, vectors, matrices, linear functionals, bilinear forms, etc. To represent a vector x as a tensor one can simply let the array associated to any basis B be the vector of coordinates of x with respect to B.

- However, to count as a tensor, the arrays need to obey a relation that precisely corresponds to how vectors, matrices, linear functionals, etc transform when one passes from one coordinate system to another.

- The modern approach

- The modern (component-free) approach views tensors initially as abstract objects, expressing some definite type of multi-linear concept. Their well-known properties can be derived from their definitions, as linear maps or more generally; and the rules for manipulations of tensors arise as an extension of linear algebra to multilinear algebra. This treatment has attempted to replace the component-based treatment for advanced study, in the way that the more modern component-free treatment of vectors replaces the traditional component-based treatment after the component-based treatment has been used to provide an elementary motivation for the concept of a vector. One could say that the slogan is 'tensors are elements of some tensor space'. Nevertheless, a component-free approach has not become fully popular, owing to the difficulties involved with giving a geometrical interpretation to higher-rank tensors.

- The intermediate treatment of tensors attempts to bridge the two extremes, and to show their relationships.

In the end the same computational content is expressed. See glossary of tensor theory for a listing of technical terms.

Tensor densities

It is also possible for a tensor field to have a "density". A tensor with density r transforms as an ordinary tensor under coordinate transformations, except that it is also multiplied by the determinant of the Jacobian to the rth power. Invariantly, in the language of multilinear algebra, one can think of tensor densities as multilinear maps taking their values in the (1-dimensional) space of n-forms (where n is the dimension of the space), as opposed to taking their values in just R. Higher "weights" then just correspond to taking additional tensor products with this space in the range. In the language of vector bundles, the determinant bundle of the tangent bundle is a line bundle that can be used to 'twist' other bundles r times.

See also

- Glossary of tensor theory

- Classical treatment of tensors

- Intermediate treatment of tensors

- Component-free treatment of tensors

Notation

- Abstract index notation

- Einstein notation

- Voigt notation

- Mandel notation

- Penrose graphical notation

- Raising and lowering indices

Foundational

- Covariance and contravariance of vectors

- Fibre bundle

- One-form

- Tensor field

- Tensor product

- Tensor product of modules

Applications

- Absolute differentiation

- Application of tensor theory in engineering

- Application of tensor theory in physics

- Curvature

- Einstein field equations

- Fluid mechanics

- Riemannian geometry

- Tensor derivative

- Structure Tensor

Historic references

- ↑ William Rowan Hamilton, On some Extensions of Quaternions

- ↑ Woldemar Voigt, Die fundamentalen physikalischen Eigenschaften der Krystalle in elementarer Darstellung (Leipzig, 1898)

- ↑ Abraham Pais, Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein

References

- Bishop, Richard L.; Samuel I. Goldberg (1980). Tensor Analysis on Manifolds. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-64039-6.

- Danielson, Donald A. (2003). Vectors and Tensors in Engineering and Physics (2/e ed.). Westview (Perseus). ISBN 978-0-8133-4080-7.

- Lawden, D. F. (2003). Introduction to Tensor Calculus, Relativity and Cosmology (3/e ed.). Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-42540-5.

- Lebedev, Leonid P.; Michael J. Cloud (2003). Tensor Analysis. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-360-0.

- Lovelock, David; Hanno Rund (1989). Tensors, Differential Forms, and Variational Principles. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65840-7.

Tensor software

- FTensor is a high performance tensor library written in C++.

- GRTensorII is a computer algebra package for performing calculations in the general area of differential geometry. GRTensor II is not a stand alone package, the program runs with all versions of Maple V Release 3 through Maple 9.5. A limited version (GRTensorM) has been ported to Mathematica.

- MathTensor is a tensor analysis system written for the Mathematica system. It provides more than 250 functions and objects for elementary and advanced users.

- Tensors in Physics is a tensor package written for the Mathematica system. It provides many functions relevant for General Relativity calculations in general Riemann-Cartan geometries.

- Maxima is a free open source computer algebra system which can be used for tensor algebra calculations - it is particularly useful for calculations with abstract tensors (i.e. when one wishes to do calculations without defining all components of the tensor explicitly). It comes with three tensor packages: itensor for abstract (indicial) tensor manipulation, ctensor for component-defined tensors, and atensor for algebraic tensor manipulation.

- Ricci is a system for Mathematica 2.x and later for doing basic tensor analysis, available for free.

- Tela is a software package similar to Matlab and Octave, but designed specifically for tensors.

- Tensor Toolbox Multilinear algebra MATLAB software.

- TTC Tools of Tensor Calculus is a Mathematica package for doing tensor and exterior calculus on differentiable manifolds.

- EDC and RGTC "Exterior Differential Calculus" and "Riemannian Geometry & Tensor Calculus" are free Mathematica packages for tensor calculus especially designed but not only for general relativity.

- Tensorial "Tensorial 4.0" is a general purpose tensor calculus package for Mathematica. Already a mature package, Tensorial was successfully applied in a broad range of fields including general relativity, continuum mechanics. A PDF image can be found at this web address .

- Cadabra "Cadabra" is a computer algebra system (CAS) designed specifically for the solution of problems encountered in field theory. It has extensive functionality for tensor polynomial simplification including multi-term symmetries, fermions and anti-commuting variables, Clifford algebras and Fierz transformations, implicit coordinate dependence, multiple index types and many more. The input format is a subset of TeX. Both a command-line and a graphical interface are available.

- TL is a multi-threaded tensor library implemented in C++ used in Dynare++. The library allows for folded/unfolded, dense/sparse tensor representations, general ranks (symmetries). The library implements Faa Di Bruno formula and is adaptive to available memory. Dynare++ is a standalone package solving higher order Taylor approximations to equilibria of non-linear stochastic models with rational expectations.

- Spartns is a Sparse Tensor framework for Common Lisp.

- xAct: Efficient Tensor Computer Algebra for Mathematica. xAct is a collection of packages for fast manipulation of tensor expressions, based on efficient algorithms of Computational Group Theory. xAct performs both abstract and component computations together, and contains special packages for high-order metric perturbation theory, invariants of the Riemann tensor, spinors, and more. Modelled on the current geometric approach to General Relativity, xAct has been already used to solve several hard problems, like that of the relations among the differential scalars of the Riemann tensor.

External links

- [1] Detailed explanation of tensors

- An Introduction to Tensors for Students of Physics and Engineering, released by NASA

- A discussion of the various approaches to teaching tensors, and recommendations of textbooks

- A Quick Introduction to Tensor Analysis by R. A. Sharipov.

- Introduction to Tensors by Joakim Strandberg.