Tennessee

| State of Tennessee | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Official language(s) | English | ||||||||||

| Demonym | Tennessean | ||||||||||

| Capital | Nashville | ||||||||||

| Largest city | Memphis | ||||||||||

| Largest metro area | Nashville Metropolitan Area | ||||||||||

| Area | Ranked 36th in the US | ||||||||||

| - Total | 42,169 sq mi (109,247 km²) |

||||||||||

| - Width | 120 miles (195 km) | ||||||||||

| - Length | 440 miles (710 km) | ||||||||||

| - % water | 2.2 | ||||||||||

| - Latitude | 34° 59′ N to 36° 41′ N | ||||||||||

| - Longitude | 81° 39′ W to 90° 19′ W | ||||||||||

| Population | Ranked 17th in the US | ||||||||||

| - Total | 6,156,719 (2007 est.)[1] | ||||||||||

| - Density | 138.0/sq mi (53.29/km²) Ranked 19th in the US |

||||||||||

| Elevation | |||||||||||

| - Highest point | Clingman's Dome 6,643 ft. ft (2,026 m) |

||||||||||

| - Mean | 900 ft (280 m) | ||||||||||

| - Lowest point | Mississippi River[2] 178 ft (54 m) |

||||||||||

| Admission to Union | June 1, 1796 (16th) | ||||||||||

| Governor | Phil Bredesen (D) | ||||||||||

| Lieutenant Governor | Ron Ramsey (R) | ||||||||||

| U.S. Senators | Lamar Alexander (R) Bob Corker (R) |

||||||||||

| Congressional Delegation | 4 R, 5 D (list) | ||||||||||

| Time zones | |||||||||||

| - East Tennessee | Eastern: UTC-5/-4 | ||||||||||

| - Middle and West | Central: UTC-6/-5 | ||||||||||

| Abbreviations | TN Tenn. US-TN | ||||||||||

| Website | www.tennessee.gov | ||||||||||

Tennessee (/tɛnɨˈsiː/) is a state located in the Southern United States. In 1796, it became the sixteenth state to join the Union. The capital city is Nashville, and the largest city is Memphis.

Contents |

Geography

- See also: List of counties in Tennessee and Geology of Tennessee

Tennessee borders eight other states: Kentucky and Virginia to the north; North Carolina to the east; Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi on the south; Arkansas and Missouri on the Mississippi River to the west. Tennessee ties Missouri as the states bordering the most other states. The state is trisected by the Tennessee River. The highest point in the state is Mt. LeConte at 6,593 feet, Clingman's Dome, which lies on Tennessee's eastern border, is the highest point on the Appalachian Trail but it is on the North Carolina side of the state line. The lowest point is the Mississippi River at the Mississippi state line. The geographical center of the state is located in Murfreesboro.

The state of Tennessee is geographically and constitutionally divided into three Grand Divisions: East Tennessee, Middle Tennessee, and West Tennessee. Tennessee features six principal physiographic regions: the Blue Ridge, the Appalachian Ridge and Valley Region, the Cumberland Plateau, the Highland Rim, the Nashville Basin, and the Gulf Coastal Plain. Tennessee is home to the most caves in the United States, with over 8,350 caves registered to date.

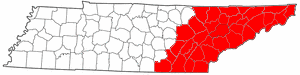

East Tennessee

The Blue Ridge area lies on the eastern edge of Tennessee, bordering North Carolina. This region of Tennessee is characterized by high mountains, including the Great Smoky Mountains, Chilhowee Mountain, the Unicoi Range, and the Iron Mountains range. The average elevation of the Blue Ridge area is 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level. Clingman's Dome is located in this region.

Stretching west from the Blue Ridge for approximately 55 miles (88 km) is the Ridge and Valley region, in which numerous tributaries join to form the Tennessee River in the Tennessee Valley. This area of Tennessee is covered by fertile valleys separated by wooded ridges, such as Bays Mountain and Clinch Mountain. The western section of the Tennessee valley, where the depressions become broader and the ridges become lower, is called the Great Valley. In this valley are numerous towns and the region's two urban areas, Knoxville, the 3rd largest city in the state, and Chattanooga, the 4th largest city in the state.

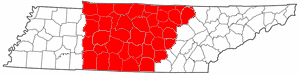

Middle Tennessee

To the west of East Tennessee lies the Cumberland Plateau; this area is covered with flat-topped mountains separated by sharp valleys. The elevation of the Cumberland Plateau ranges from 1,500 to 1,800 feet (450 to 550 m) above sea level. West of the Cumberland Plateau is the Highland Rim, an elevated plain that surrounds the Nashville Basin. The northern section of the Highland Rim, known for its high tobacco production, is sometimes called the Pennyroyal Plateau and is located in primarily in Southwestern Kentucky. The Nashville Basin is characterized by rich, fertile farm country and high natural wildlife diversity.

Middle Tennessee was a common destination of settlers crossing the Appalachians in the late 1700s and early 1800s. An important trading route called the Natchez Trace, first used by Native Americans, connected Middle Tennessee to the lower Mississippi River town of Natchez. Today the route of the Natchez Trace is a scenic highway called the Natchez Trace Parkway.

Many biologists study the area's salamander species because the diversity is greater there than anywhere else in the U.S. This is thought to be because of the clean Appalachian foothill springs that abound in the area. Some of the last remaining large American Chestnut trees still grow in this region and are being used to help breed blight resistant trees.

West Tennessee

West of the Highland Rim and Nashville Basin is the Gulf Coastal Plain, which includes the Mississippi embayment. The Gulf Coastal Plain is, in terms of area, the predominant land region in Tennessee. It is part of the large geographic land area that begins at the Gulf of Mexico and extends north into southern Illinois. In Tennessee, the Gulf Coastal Plain is divided into three sections that extend from the Tennessee River in the east to the Mississippi River in the west. The easternmost section, about 10 miles (16 km) in width, consists of hilly land that runs along the western bank of the Tennessee River. To the west of this narrow strip of land is a wide area of rolling hills and streams that stretches all the way to Memphis; this area is called the Tennessee Bottoms or bottom land. In Memphis, the Tennessee Bottoms end in steep bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. To the west of the Tennessee Bottoms is the Mississippi Alluvial Plain, less than 300 feet (90 m) above sea level. This area of lowlands, flood plains, and swamp land is sometimes referred to as the Delta region.

Most of West Tennessee remained Indian land until the Chickasaw Cession of 1818, when the Chickasaw ceded their land between the Tennessee River and the Mississippi River. The portion of the Chickasaw Cession that lies in Kentucky is known today as the Jackson Purchase.

Public lands

Areas under the control and management of the National Park Service include:

- Andrew Johnson National Historic Site in Greeneville

- Appalachian National Scenic Trail

- Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area

- Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

- Foothills Parkway

- Fort Donelson National Battlefield and Fort Donelson National Cemetery near Dover

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- Natchez Trace Parkway

- Obed Wild and Scenic River near Wartburg

- Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail

- Shiloh National Cemetery and Shiloh National Military Park near Shiloh

- Stones River National Battlefield and Stones River National Cemetery near Murfreesboro

- Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

Fifty-four state parks, covering some 132,000 acres (534 km²) as well as parts of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Cherokee National Forest, and Cumberland Gap National Historical Park are in Tennessee. Sportsmen and visitors are attracted to Reelfoot Lake, originally formed by an earthquake; stumps and other remains of a once dense forest, together with the lotus bed covering the shallow waters, give the lake an eerie beauty.

See also: List of Tennessee state parks

Climate

Most of the state has a humid subtropical climate, with the exception of the higher mountains, which have a humid continental climate. The Gulf of Mexico is the dominant factor in the climate of Tennessee, with winds from the south being responsible for most of the state's annual precipitation. Generally, the state has hot summers and mild to cool winters with generous precipitation throughout the year. On average the state receives 50 inches (130 cm) of precipitation annually. Snowfall ranges from 5 inches (13 cm) in West Tennessee to over 16 inches (41 cm) in the higher mountains in East Tennessee.[3]

Summers in the state are generally hot, with most of the state averaging a high of around 90 °F (32 °C) during the summer months. Summer nights tend to be cooler in East Tennessee. Winters tend to be mild to cool, increasing in coolness at higher elevations and in the east. Generally, for areas outside the highest mountains, the average overnight lows are near freezing for most of the state.

While the state is far enough from the coast to avoid any direct impact from a hurricane, the location of the state makes it likely to be impacted from the remnants of tropical cyclones which weaken over land and can cause significant rainfall. The state averages around 50 days of thunderstorms per year, some of which can be quite severe. Tornadoes are possible throughout the state, with West Tennessee slightly more vulnerable.[4] On average, the state has 15 tornadoes per year.[5] Tornadoes in Tennessee can be severe, and Tennessee leads the nation in the percentage of total tornadoes which have fatalities.[6] Winter storms are an occasional problem—made worse by a lack of snow removal equipment and a population which might not be accustomed or equipped to travel in snow—although ice storms are a more likely occurrence. Fog is a persistent problem in parts of the state, especially in much of the Smoky Mountains.

| Monthly Normal High and Low Temperatures For Various Tennessee Cities (F)[2] | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chattanooga | 49/30 | 54/33 | 63/40 | 72/47 | 79/56 | 86/65 | 90/69 | 89/68 | 82/62 | 72/48 | 61/40 | 52/33 |

| Knoxville | 46/29 | 52/32 | 60/39 | 69/47 | 76/56 | 84/64 | 87/68 | 86/67 | 81/61 | 70/48 | 59/39 | 50/32 |

| Memphis | 49/31 | 54/36 | 63/44 | 72/52 | 80/61 | 88/69 | 92/73 | 91/71 | 85/64 | 75/52 | 62/43 | 52/34 |

| Nashville | 46/28 | 51/31 | 61/39 | 70/47 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 89/70 | 88/68 | 82/61 | 71/49 | 59/40 | 49/32 |

| Oak Ridge | 46/27 | 52/30 | 61/37 | 70/44 | 78/53 | 85/62 | 88/66 | 87/65 | 81/59 | 71/46 | 59/36 | 49/30 |

History

Early history

The area now known as Tennessee was first inhabited by Paleo-Indians nearly 12,000 years ago.[7] The names of the cultural groups that inhabited the area between first settlement and the time of European contact are unknown, but several distinct cultural phases have been named by archaeologists, including Archaic (8000-1000 B.C.), Woodland (1000 B.C. - 1000 A.D.), and Mississippian (1000-1600 A.D.), whose chiefdoms were the cultural predecessors of the Muscogee people who inhabited the Tennessee River Valley prior to Cherokee migration into the river's headwaters.

When Spanish explorers first visited the area, led by Hernando de Soto in 1539–43, it was inhabited by tribes of Muscogee and Yuchi people. Possibly because of European diseases devastating the Native tribes, which would have left a population vacuum, and also from expanding European settlement in the north, the Cherokee moved south from the area now called Virginia. As European colonists spread into the area, the native populations were forcibly displaced to the south and west, including all Muscogee and Yuchi peoples, the Chickasaw, and Choctaw.

The first British settlement in what is now Tennessee was Fort Loudoun, near present- day Vonore, Tennessee. Fort Loudoun became the westernmost British outpost to that date. The fort was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm and constructed by forces under British Captain Raymond Demeré. After its completion, Captain Raymond Demeré relinquished command on 14 August 1757 to his brother, Captain Paul Demeré. Hostilities erupted between the British and the neighboring Overhill Cherokees, and a siege of Fort Loudoun ended with its surrender on 7 August 1760. The following morning, Captain Paul Demeré and many of his men were killed in an engagement nearby.

Early during the American Revolutionary War, Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals (in present day Elizabethton) was attacked in 1776 by Dragging Canoe and his warring faction of Cherokee (also referred to by settlers as the Chickamauga) opposed to the Transylvania Purchase and aligned with the British Loyalists. The lives of many settlers were spared through the warnings of Dragging Canoe's cousin Nancy Ward. The frontier fort on the banks of the Watauga River later served as a 1780 staging area for the Overmountain Men in preparation to trek over the Appalachian Mountains, to engage, and to later defeat the British Army at the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina.

Eight counties of western North Carolina (and now part of Tennessee) broke off from that state in the late 1780s and formed the abortive State of Franklin. Efforts to obtain admission to the Union failed, and the counties had re-joined North Carolina by 1790. North Carolina ceded the area to the federal government in 1790, after which it was organized into the Southwest Territory. In an effort to encourage settlers to move west into the new territory of Tennessee, in 1787 the mother state of North Carolina ordered a road to be cut to take settlers into the Cumberland Settlements—from the south end of Clinch Mountain (in East Tennessee) to French Lick (Nashville). The Trace was called the “North Carolina Road” or “Avery’s Trace,” and sometimes “The Wilderness Road.” It should not be confused with Daniel Boone's road through Cumberland Gap.

Statehood

Tennessee was admitted to the Union in 1796 as the 16th state. The state boundaries, according to the Constitution of the State of Tennessee, Article I, Section 31, stated that the beginning point for identifying the boundary was the extreme height of the Stone Mountain, at the place where the line of Virginia intersects it, and basically ran the extreme heights of mountain chains through the Appalachian Mountains separating North Carolina from Tennessee past the Indian towns of Cowee and Old Chota, thence along the main ridge of the said mountain (Unicoi Mountain) to the southern boundary of the state; all the territory, lands and waters lying west of said line are included in the boundaries and limits of the newly formed state of Tennessee. Part of the provision also stated that the limits and jurisdiction of the state would include future land acquisition, referencing possible land trade with other states, or the acquisition of territory from west of the Mississippi River.

During the administration of U.S. President Martin Van Buren, nearly 17,000 Cherokees were uprooted from their homes between 1838 and 1839 and were forced by the U.S. military to march from "emigration depots" in Eastern Tennessee (such as Fort Cass) toward the more distant Indian Territory west of Arkansas. During this relocation an estimated 4,000 Cherokees died along the way west.[8] In the Cherokee language, the event is called Nunna daul Isunyi—"the Trail Where We Cried." The Cherokees were not the only Native Americans forced to emigrate as a result of the Indian removal efforts of the United States, and so the phrase "Trail of Tears" is sometimes used to refer to similar events endured by other Native American peoples, especially among the "Five Civilized Tribes." The phrase originated as a description of the earlier emigration of the Choctaw nation.

Civil War, Reconstruction and Jim Crow

Tennessee was the last border state to secede from the Union because of many threats from the Union. Ignoring all threats it joined the Confederate States of America on June 8, 1861. Many major battles of the American Civil War were fought in Tennessee—most of them Union victories. Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy captured control of the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers in February 1862. They held off the Confederate counterattack at Shiloh in April. Memphis fell to the Union in June, following a naval battle on the Mississippi River in front of the city. Capture of Memphis and Nashville gave the Union control of the western and middle sections; this control was confirmed at the Battle of Murfreesboro in early January 1863 and by the subsequent Tullahoma Campaign.

Confederates held East Tennessee despite the strength of Unionist sentiment there, with the exception of extremely pro-Confederate Sullivan County. The Confederates besieged Chattanooga in early fall 1863, but were driven off by Grant in November. Many of the Confederate defeats can be attributed to the poor strategic vision of General Braxton Bragg, who led the Army of Tennessee from Perryville, Kentucky to Confederate defeat at Chattanooga.

The last major battles came when the Confederates invaded Middle Tennessee in November 1864 and were checked at Franklin, then totally destroyed by George Thomas at Nashville in December. Meanwhile the civilian Andrew Johnson was appointed military governor of the state by President Abraham Lincoln.

When the Emancipation Proclamation was announced, Tennessee was mostly held by Union forces. Thus, Tennessee was not among the states enumerated in the Proclamation, and the Proclamation did not free any slaves there. Nonetheless, enslaved African Americans escaped to Union lines to gain freedom without waiting for official action. Old and young, men, women and children camped near Union troops. Thousands of former slaves ended up fighting on the Union side, nearly 200,000 in total across the South.

Tennessee's legislature approved an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting slavery on February 22, 1865.[9] Voters in the state approved the amendment in March.[10] It also ratified the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (abolishing slavery in every state) on April 7, 1865.

In 1864, Andrew Johnson (a War Democrat from Tennessee) was elected Vice President under Abraham Lincoln. He became President after Lincoln's assassination in 1865. Under Johnson's lenient re-admission policy, Tennessee was the first of the seceding states to have its elected members readmitted to the U.S. Congress, on July 24, 1866. Because Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, it was the only one of the formerly seceded states that did not have a military governor during the Reconstruction period.

After the formal end of Reconstruction, the struggle over power in Southern society continued. Through violence and intimidation against freedmen and their allies, white Democrats regained political power in Tennessee and other states across the South in the late 1870s and 1880s. Over the next decade, the white-dominated state legislature passed increasingly restrictive laws to control African Americans. In 1889 the General Assembly passed four laws described as electoral reform, with the cumulative effect of essentially disfranchising most African Americans in rural areas and small towns, as well as many poor whites. Legislation included implementation of a poll tax, timing of registration, and recording requirements. Tens of thousands of taxpaying citizens were without representation for decades into the 20th century.[11] Disfranchising legislation accompanied Jim Crow laws passed in the late 19th century, which imposed segregation in the state. In 1900, African Americans made up nearly 24% of the state's population, and numbered 480,430 citizens who lived mostly in the central and western parts of the state.[12]

In 1897, Tennessee celebrated its centennial of statehood (though one year late of the 1896 anniversary) with a great exposition in Nashville. A full scale replica of the Parthenon was constructed for the celebration, located in what is now Nashville's Centennial Park.

20th century

On 18 August 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth and final state necessary to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which provided women the right to vote. Disfranchising voter registration requirements continued to keep most African Americans and many poor whites, both men and women, off the voter rolls.

The need to create work for the unemployed during the Great Depression, a desire for rural electrification, the need to control annual spring flooding and improve shipping capacity on the Tennessee River were all factors that drove the Federal creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1933. Through the power of the TVA projects, Tennessee quickly became the nation's largest public utility supplier.

During World War II, the availability of abundant TVA electrical power led the Manhattan Project to locate one of the principal sites for production and isolation of weapons-grade fissile material in East Tennessee. The planned community of Oak Ridge was built from scratch to provide accommodations for the facilities and workers. These sites are now Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the Y-12 National Security Complex, and the East Tennessee Technology Park.

Despite recognized effects of limiting voting by poor whites, successive legislatures expanded the reach of the disfranchising laws until they covered the state. In 1949 political scientist V. O. Key Jr. argued that "the size of the poll tax did not inhibit voting as much as the inconvenience of paying it. County officers regulated the vote by providing opportunities to pay the tax (as they did in Knoxville), or conversely by making payment as difficult as possible. Such manipulation of the tax, and therefore the vote, created an opportunity for the rise of urban bosses and political machines. Urban politicians bought large blocks of poll tax receipts and distributed them to blacks and whites, who then voted as instructed."[13]

In 1953 state legislators amended the state constitution, removing the poll tax. In many areas both blacks and poor whites still faced subjectively applied barriers to voter registration that did not end until after passage of national civil rights legislation, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[14]

Tennessee celebrated its bicentennial in 1996. With a yearlong statewide celebration entitled "Tennessee 200", it opened a new state park (Bicentennial Mall) at the foot of Capitol Hill in Nashville.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 35,691 |

|

|

| 1810 | 261,727 |

|

|

| 1820 | 422,823 | 61.6% | |

| 1830 | 681,904 | 61.3% | |

| 1840 | 829,210 | 21.6% | |

| 1870 | 1,258,520 |

|

|

| 1880 | 1,542,359 | 22.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,020,616 |

|

|

| 1910 | 2,184,789 | 8.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,337,885 | 7% | |

| 1930 | 2,616,556 | 11.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,915,841 | 11.4% | |

| 1950 | 3,291,718 | 12.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,567,089 | 8.4% | |

| 1970 | 3,923,687 | 10% | |

| 1980 | 4,591,120 | 17% | |

| 1990 | 4,877,185 | 6.2% | |

| 2000 | 5,689,283 | 16.7% | |

| Est. 2007 | 6,156,719 | 8.2% | |

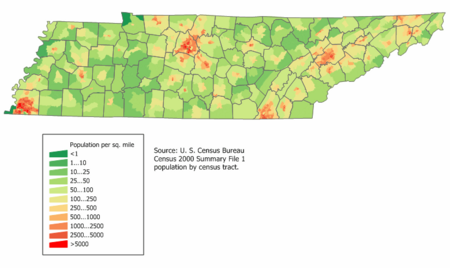

The center of population of Tennessee is located in Rutherford County, in the city of Murfreesboro.[15]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2006, Tennessee has an estimated population of 6,038,803, which is an increase of 83,058, or 1.4%, from the prior year and an increase of 349,541, or 6.1%, since the year 2000. This includes a natural increase since the last census of 142,266 people (that is 493,881 births minus 351,615 deaths) and an increase from net migration of 219,551 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 59,385 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 160,166 people.

| Demographics of Tennessee (csv) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By race | White | Black | AIAN* | Asian | NHPI* |

| 2000 (total population) | 82.08% | 16.81% | 0.69% | 1.22% | 0.08% |

| 2000 (Hispanic only) | 1.99% | 0.14% | 0.05% | 0.03% | 0.02% |

| 2005 (total population) | 81.53% | 17.22% | 0.69% | 1.47% | 0.09% |

| 2005 (Hispanic only) | 2.81% | 0.17% | 0.06% | 0.03% | 0.02% |

| Growth 2000–05 (total population) | 4.11% | 7.37% | 3.86% | 26.24% | 12.40% |

| Growth 2000–05 (non-Hispanic only) | 3.02% | 7.23% | 2.41% | 26.26% | 12.66% |

| Growth 2000–05 (Hispanic only) | 48.16% | 24.52% | 22.34% | 25.23% | 11.23% |

| * AIAN is American Indian or Alaskan Native; NHPI is Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | |||||

In 2000, the five most common self-reported ethnic groups in the state were: American (17.3%), African American (16.4%), Irish (9.3%), English (9.1%), and German (8.3%).[3]

The state's African-American population is concentrated mainly in rural West and Middle Tennessee and the cities of Memphis, Nashville, Clarksville, Chattanooga, and Knoxville.

6.6% of Tennessee's population were reported as under 5 years of age, 24.6% under 18, and 12.4% were 65 or older. Females made up approximately 51.3% of the population.

Now almost 20% of Tennesseans were born outside the South, though such people had been only 13.5% of the total population in 1990.[16]

Religion

The religious affiliations of the people of Tennessee are: [17]

- Christian: 82%

- Baptist: 39%

- Methodist: 10%

- Church of Christ: 6%

- Roman Catholic: 6%

- Presbyterian: 3%

- Church of God: 2%

- Lutheran: 2%

- Pentecostal: 2%

- Other Christian (includes unspecified "Christian" and "Protestant"): 12%

- Other religions: 3%

- Non-religious: 9%

The largest denominations by number of adherents in 2000 were the Southern Baptist Convention with 1,414,199; the United Methodist Church with 393,994; the Churches of Christ with 216,648; and the Roman Catholic Church with 183,161.[20]

Tennessee is home to several Protestant denominations, such as the Church of God in Christ, the Church of God and The Church of God of Prophecy, both located in (Cleveland, Tennessee), and the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. The Free Will Baptist denomination is headquartered in Antioch, and its main bible college is in Nashville. The Southern Baptist Convention maintains its general headquarters in Nashville. Publishing houses of several denominations are located in Nashville.

The state's small Roman Catholic, Muslim, and Jewish communities are mainly centered in the metropolitan areas of Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville and Chattanooga.

Economy

According to U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 2005 Tennessee's gross state product was $226.502 billion, making Tennessee the 18th largest economy in the nation. In 2003, the per capita personal income was $28,641, 36th in the nation, and 91% of the national per capita personal income of $31,472. In 2004, the median household income was $38,550, 41st in the nation, and 87% of the national median of $44,472.

Major outputs for the state include textiles, cotton, cattle, and electrical power. As proof of interest in beef production, Tennessee has over 82,000 farms, and beef cattle are found in roughly 59 percent of the farms in the state. [4] Although cotton was an early crop in Tennessee, large-scale cultivation of the fiber did not begin until the 1820s with the opening of the land between the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers. The upper wedge of the Mississippi Delta extends into southwestern Tennessee, and it was in this fertile section that cotton took hold. Currently West Tennessee is also heavily planted in soybeans, focusing on the northwest corner of the state.[21]

Major corporations with headquarters in Tennessee include FedEx Corporation, AutoZone Incorporated and International Paper, all based in Memphis; Pilot Corporation, based in Knoxville; Eastman Chemical Company, based in Kingsport; and the North American headquarters of Nissan, based in Franklin.

The Tennessee income tax does not apply to salaries and wages, but most income from stocks, bonds and notes receivable is taxable. All taxable dividends and interest which exceed the $1,250 single exemption or the $2,500 joint exemption are taxable at the rate of 6%. The state's sales and use tax rate for most items is 7%. Food is taxed at a lower rate of 5.5%, but candy, dietary supplements and prepared food are taxed at the full 7% rate. Local sales taxes are collected in most jurisdictions, at rates varying from 1.5% to 2.75%, bringing the total sales tax to between 8.5% and 9.75%, one of the highest levels in the nation. Intangible property is assessed on the shares of stock of stockholders of any loan company, investment company, insurance company or for-profit cemetery companies. The assessment ratio is 40% of the value multiplied by the tax rate for the jurisdiction. Tennessee imposes an inheritance tax on decedents' estates that exceed maximum single exemption limits ($1,000,000 for deaths 2006 and after; [5]).

Tennessee is a right to work state, as are most of its Southern neighbors. Unionization has historically been low and continues to decline as in most of the U.S. generally.

Transportation

Interstate highways

Interstate 40 crosses the state in an east-west orientation. Its branch interstate highways include I-240 in Memphis; I-440 and I-840 in Nashville; and I-140 and I-640 in Knoxville. I-26, although technically an east-west interstate, runs from the North Carolina border below Johnson City to its terminus at Kingsport. I-24 is an east-west interstate that runs cross-state from Chattanooga to Clarksville.

In a north-south orientation are highways I-55, I-65, I-75, and I-81. Interstate 65 crosses the state through Nashville, while Interstate 75 serves Chattanooga and Knoxville and Interstate 55 serves Memphis. Interstate 81 enters the state at Bristol and terminates at its junction with I-40 near Dandridge. I-155 is a branch highway from I-55.

Airports

Major airports within the state include Nashville International Airport (BNA), Memphis International Airport (MEM), McGhee Tyson Airport (TYS) in Knoxville, Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport (CHA), Tri-Cities Regional Airport (TRI), and McKellar-Sipes Regional Airport (MKL), in Jackson. Because Memphis International Airport is the major hub for FedEx Corporation, it is the world's largest air cargo operation.

Railroads

Memphis and Dyersburg, Tennessee, are served by the Amtrak City of New Orleans line on its run between Chicago, Illinois and New Orleans, Louisiana.

Law and government

Tennessee's governor holds office for a four-year term and may serve a maximum of two terms. The governor is the only official who is elected statewide, making him one of the more powerful chief executives in the nation. The state does not elect the lieutenant-governor directly, contrary to most other states; the Tennessee Senate elects its Speaker who serves as lieutenant governor.

The Tennessee General Assembly, the state legislature, consists of the 33-member Senate and the 99-member House of Representatives. Senators serve four-year terms, and House members serve two-year terms. Each chamber chooses its own speaker. The speaker of the state Senate also holds the title of lieutenant-governor. Most executive officials are elected by the legislature.

The highest court in Tennessee is the state Supreme Court. It has a chief justice and four associate justices. No more than two justices can be from the same Grand Division. The Supreme Court of Tennessee also appoints the Attorney General, which is not found among any of the other 49 states in the Union. The Court of Appeals has 12 judges. The Court of Criminal Appeals has 12 judges.[22]

Tennessee's current state constitution was adopted in 1870. The state had two earlier constitutions. The first was adopted in 1796, the year Tennessee joined the union, and the second was adopted in 1834. The Tennessee Constitution outlaws martial law within its jurisdiction. This may be a result of the experience of Tennessee residents and other Southerners during the period of military control by Union (Northern) forces of the U.S. government after the American Civil War.

Politics

Tennessee politics, like that of most U.S. states, is dominated by the Democratic and Republican Parties. After going for Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower twice in the 1950s, Tennessee currently tilts towards the Republican Party, but tends to be politically moderate.

While the Republicans control slightly more than half of the state, Democrats have strong support in the cities of Memphis and Nashville and in parts of Middle Tennessee (although declining, due to the growth of suburban Nashville) and in West Tennessee north of Memphis.[23] The latter area includes a large rural African-American population.[24] Historically, Republicans had their greatest strength in East Tennessee prior to the 1960s. Tennessee's 1st / 2nd congressional districts based in East Tennessee are one of the few ancestrally Republican districts in the South; the 1st has been in Republican hands continuously since 1881, and the 2nd district has been held continuously by Republicans since 1873.

In contrast, long disfranchisement of African Americans and their proportion as a minority (16.45% in 1960) meant that white Democrats generally dominated politics in the rest of the state until the 1960s. The GOP in Tennessee was essentially a sectional party. Former Gov. Winfield Dunn and former U.S. Sen. Bill Brock wins in 1970 built the Tennessee Republican Party into a competitive party for the statewide victory.[25] Tennessee has selected governors from different parties since 1966.

In the 2000 Presidential Election, the majority of Tennessee voters voted for Republican George W. Bush rather than Vice President Al Gore, a former U.S. Senator from Tennessee. Tennessee support for Bush increased in 2004, with his margin of victory in the state increasing from 4% in 2000 to 14% in 2004.[26] Southern Democratic nominees (e.g., Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton) usually fare better in Tennessee, especially among split-ticket voters outside the metropolitan areas.

Tennessee sends nine members to the US House of Representatives, of whom there are five Democrats and four Republicans. Lieutenant Governor Ron Ramsey is the first Republican speaker of the state Senate in 140 years. In 2008 elections, the Republican party gained control of both houses of the Tennessee state legislature for the first time since Reconstruction.[6]

The Baker v. Carr (1962) decision of the US Supreme Court, which established the principle of one man, one vote, was based on a lawsuit over rural-biased apportionment of seats in the Tennessee legislature.[27][28][29] The significant ruling led to an increased (and proportional) prominence in state politics by urban and, eventually, suburban, legislators and statewide officeholders in relation to their population within the state. The ruling also applied to numerous other states long controlled by rural minorities, such as Alabama.

See also: List of Tennessee Governors, U.S. Congressional Delegations from Tennessee, Maps of congressional districts

Law enforcement

The State of Tennessee maintains two dedicated law enforcement entities, the Tennessee Highway Patrol and the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA), as well as the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation (TBI) and the Tennessee State Parks department.

The Highway Patrol is the primary law enforcement entity that concentrates on highway safety regulations and general non-game state law enforcement and is under the jurisdiction of the Tennessee Department of Safety. The TWRA is an independent agency tasked with enforcing all wild game, boating, and fisheries regulations outside of state parks. The TBI maintains state-of-the-art investigative facilities and is the primary state-level criminal investigative department. Tennessee State Park Rangers are responsible for all activities and law enforcement inside the Tennessee State Parks system.

Important cities and towns

- See also: List of cities and towns in Tennessee

The capital is Nashville, though Knoxville, Kingston, and Murfreesboro have all served as state capitals in the past. Memphis has the largest population of any city in the state, but Nashville has had the state's largest metropolitan area since circa 1990; Memphis formerly held that title. Chattanooga and Knoxville, both in the eastern part of the state near the Great Smoky Mountains, each has approximately one-third of the population of Memphis or Nashville. The city of Clarksville is a fifth significant population center, some 45 miles (70 km) northwest of Nashville. Murfreesboro is the sixth-largest city in Tennessee, consisting of some 100,500 residents.

|

Major cities Secondary cities

|

Education

Colleges and universities

|

|

Sports

Professional teams

| Club | Sport | League |

|---|---|---|

| Memphis Redbirds | Baseball | Pacific Coast League (Triple-A) |

| Nashville Sounds | Baseball | Pacific Coast League (Triple-A) |

| Chattanooga Lookouts | Baseball | Southern League (Double-A) |

| Tennessee Smokies | Baseball | Southern League (Double-A) |

| West Tenn Diamond Jaxx | Baseball | Southern League (Double-A) |

| Elizabethton Twins | Baseball | Appalachian League (Rookie) |

| Greeneville Astros | Baseball | Appalachian League (Rookie) |

| Johnson City Cardinals | Baseball | Appalachian League (Rookie) |

| Kingsport Mets | Baseball | Appalachian League (Rookie) |

| Memphis Grizzlies | Basketball | National Basketball Association |

| Tennessee Titans | Football | National Football League |

| Nashville Predators | Ice hockey | National Hockey League |

| Knoxville Ice Bears | Ice hockey | Southern Professional Hockey League |

| Nashville Metros | Soccer | USL Premier Development League |

Tennessee is also home to Bristol Motor Speedway which features NASCAR Sprint Cup racing two weekends a year, routinely selling out more than 160,000 seats on each date.

Name origin

The earliest variant of the name that became Tennessee was recorded by Captain Juan Pardo, the Spanish explorer, when he and his men passed through a Native American village named "Tanasqui" in 1567 while traveling inland from South Carolina. European settlers later encountered a Cherokee town named Tanasi (or "Tanase") in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee. The town was located on a river of the same name (now known as the Little Tennessee River). It is not known whether this was the same town as the one encountered by Juan Pardo, although recent research suggests that Pardo's "Tanasqui" was located at the confluence of the Pigeon River and the French Broad River, near modern Newport.[30]

The meaning and origin of the word are uncertain. Some accounts suggest it is a Cherokee modification of an earlier Yuchi word. It has been said to mean "meeting place", "winding river", or "river of the great bend".[7][8] According to James Mooney, the name "can not be analyzed" and its meaning is lost (Mooney, pg. 534).

The modern spelling, Tennessee, is attributed to James Glen, the governor of South Carolina, who used this spelling in his official correspondence during the 1750s. In 1788, North Carolina created "Tennessee County", the third county to be established in what is now Middle Tennessee. (Tennessee County was the predecessor to current-day Montgomery County and Robertson County). When a constitutional convention met in 1796 to organize a new state out of the Southwest Territory, it adopted "Tennessee" as the name of the state.

Nickname

Tennessee is known as the "Volunteer State", a nickname earned during the War of 1812 because of the prominent role played by volunteer soldiers from Tennessee, especially during the Battle of New Orleans.[31]

State symbols

State symbols include:

- State bird - "Mockingbird"

- State game bird - "Bobwhite Quail"

- State wild animal - "Raccoon"

- State sport fish - "Largemouth Bass"

- State commercial fish - "Channel Catfish"

- State horse - "Tennessee Walking Horse"

- State insect - "Lightning Bug and the Lady Bug"

- State flower - "Purple Iris"

- State wild flower - "Passion Flower"

- State tree - "Tulip Poplar"

- State fruit - "Tomato"

See also

- List of Tennessee-related topics

References

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/popest/states/NST-ann-est.html 2007 Population Estimates

- ↑ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey (29 April 2005). Retrieved on November 7, 2006.

- ↑ "A look at Tennessee Agriculture" (PDF). Agclassroom.org. Retrieved on November 1, 2006.

- ↑ "US Thunderstorm distribution". src.noaa.gov. Retrieved on November 1, 2006.

- ↑ "Mean Annual Average Number of Tornadoes 1953-2004". ncdc.noaa.gov. Retrieved on November 1, 2006.

- ↑ "Top ten list". tornadoproject.com. Retrieved on November 1, 2006.

- ↑ "Archaeology and the Native Peoples of Tennessee". University of Tennessee, Frank H. McClung Museum. Retrieved on December 5, 2007.

- ↑ Satz, Ronald. Tennessee's Indian Peoples. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-285-3.

- ↑ "Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War". University of Maryland: Department of History.

- ↑ "This Honorable Body: African American Legislators in 19th Century Tennessee". Tennessee State Library and Archives.

- ↑ Disfranchising Laws, The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, Accessed 11 Mar 2008

- ↑ [http;//fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/php/state.php Historical Census Browser, 1900 US Census, University of Virginia], accessed 15 Mar 2008

- ↑ Disfranchising Laws, The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, Accessed 11 Mar 2008

- ↑ Disfranchising Laws, The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, Accessed 11 Mar 2008

- ↑ "Population and Population Centers by State: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on 2008-12-06.

- ↑ DADE, COREY (NOVEMBER 22, 2008). "Tennessee Resists Obama Wave", Wall Street Journal. Retrieved on 2008-11-23.

- ↑ American Religious Identification Survey (2001). Five percent of the people surveyed refused to answer.

- ↑ The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

- ↑ The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

- ↑ http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/reports/state/47_2000.asp

- ↑ [1] USDA 2002 Census of Agriculture, Maps and Cartographic Resources.

- ↑ Court of Criminal Appeals

- ↑ Map - Tennessee 2000 Election Mapper

- ↑ Tennessee by County - GCT-PL. Race and Hispanic or Latino 2000 U.S. Census Bureau

- ↑ STATESMEN’S DINNER BEST EVER

- ↑ Tennessee: McCain Leads Both Democrats by Double Digits Rasumussen Reports, April 6, 2008

- ↑ Eisler, Kim Isaac (1993). A Justice for All: William J. Brennan, Jr., and the decisions that transformed America. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671767879.

- ↑ Peltason, Jack W. (1992). "Baker v. Carr". in Hall, Kermit L. (ed.). The Oxford companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 67–70. ISBN 0195058356.

- ↑ Tushnet, Mark (2008). I dissent: Great Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 151–166. ISBN 9780807000366.

- ↑ Charles Hudson, The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Explorations of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568 (Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2005), 36-40.

- ↑ "Brief History of Tennessee in the War of 1812". Tennessee State Library and Archives. Retrieved on April 30, 2006. Other sources differ on the origin of the state nickname; according to the Columbia Encyclopedia, the name refers to volunteers for the Mexican-American War.

Further reading

- Bergeron, Paul H. Antebellum Politics in Tennessee. University of Kentucky Press, 1982.

- Bontemps, Arna. William C. Handy: Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. Macmillan Company: New York, 1941.

- Brownlow, W. G. Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession: With a Narrative of Personal Adventures among the Rebels (1862)

- Cartwright, Joseph H. The Triumph of Jim Crow: Tennessee’s Race Relations in the 1880s. University of Tennessee Press, 1976.

- Cimprich, John. Slavery's End in Tennessee, 1861-1865 University of Alabama, 1985.

- Finger, John R. "Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition". Indiana University Press, 2001.

- Honey, Michael K. Southern Labor and Black Civil Rights: Organizing Memphis Workers. University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Lamon, Lester C. Blacks in Tennessee, 1791-1970. University of Tennessee Press, 1980.

- Mooney, James. "Myths of the Cherokee". 1900, reprinted Dover: New York, 1995.

- Norton, Herman. Religion in Tennessee, 1777-1945. University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

- Schaefer, Richard T. "Sociology Matters". New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN 0-07-299775-3

- Van West, Carroll. Tennessee history: the land, the people, and the culture University of Tennessee Press, 1998.

- Van West, Carroll, ed. The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. 1998.

External links

- State Government Website

- Tennessee State Databases - Annotated list of searchable databases produced by Tennessee state agencies and compiled by the Government Documents Roundtable of the American Library Association.

- Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture

- Tennessee State Library and Archives

- Energy Profile for Tennessee

- USGS real-time, geographic, and other scientific resources of Tennessee

- U.S. Census Bureau

- Tennessee Blue Book - All things Tennessee

- Timeline of Modern Tennessee Politics

- Tennessee State Facts

- Tennessee landforms

- Interactive Tennessee for Kids

- The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century - a history by J. G. M. Ramsey, 1853

- "BillHobbs.com" Tennessee's best-known and longest-running political news and commentary blog focused primarily on Tennessee politics and media.

- Tennessee at the Open Directory Project

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Preceded by Kentucky |

List of U.S. states by date of statehood Admitted on June 1, 1796 (16th) |

Succeeded by Ohio |