Tamoxifen

|

|

|

|

|

Tamoxifen

|

|

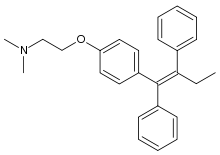

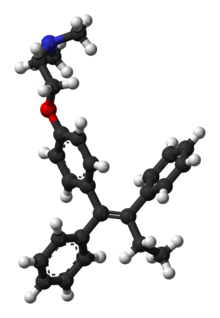

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (Z)-2-[4-(1,2-diphenylbut-1-enyl)phenoxy]-N,N-dimethyl-ethanamine | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | L02 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C26H29NO |

| Mol. mass | 371.515 g/mol 563.638 g/mol (citrate salt) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4, 2C9 and 2D6) |

| Half life | 5–7 days |

| Excretion | Fecal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | |

| Legal status | |

| Routes | Oral |

Tamoxifen is an orally taken selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that is used in the treatment of breast cancer and is currently the world's largest selling drug for that purpose.

Tamoxifen was discovered by ICI Pharmaceuticals[1] (now AstraZeneca) and is sold under the trade names Nolvadex, Istubal, and Valodex. However, the drug, even before its patent expiration, was and still is widely referred to by its generic name "tamoxifen."

Contents |

Breast cancer treatment

Tamoxifen is currently used for the treatment of both early and advanced ER+ (estrogen receptor positive) breast cancer in pre- and post-menopausal women.[2] It is also approved by the FDA for the prevention of breast cancer in women at high risk of developing the disease.[3] It has been further approved for the reduction of contralateral (in the opposite breast) cancer.

Comparative studies

In 2006, the large STAR clinical study concluded that raloxifene is equally effective in reducing the incidence of breast cancer, but after an average 4-year follow-up there were 36 % fewer uterine cancers and 29 % fewer blood clots than in women taking raloxifen.[4][5]

In 2005, the ATAC trial showed that after average 68 months following a 5 year adjuvant treatment, the group that received anastrozole (Arimidex) had significantly better results than the tamoxifen group. Anastrozole vs tamoxifen: deaths - 575 vs 651, recurrences - 402 vs 498, distant metastases - 324 vs 375, second breast cancer - 35 vs 59 (42% reduction). The trial suggested that anastrozole should be the preferred medication for postmenopausal women with localized breast cancer that is estrogen receptor (ER) positive.[6] Another study found that the risk of reoccurrence was reduced 40% (with some risk of bone fracture) and that ER negative patients also benefited from switching to Arimdex.[7][8]

Other uses

Infertility

Tamoxifen is used to treat infertility in women with anovulatory disorders. A dose of 10–40 mg per day is administered in days 3–7 of a woman's cycle.[9] In addition, a rare condition occasionally treated with tamoxifen is retroperitoneal fibrosis.[10]

Gynecomastia

In men, tamoxifen is sometimes used to treat gynecomastia that arises for example as a side effect of antiandrogen prostate cancer treatment.[11] Tamoxifen is also used by bodybuilders to prevent or reduce drug-induced gynecomastia caused by the estrogenic metabolites of anabolic steroids.[12] Tamoxifen is also sometimes used to treat or prevent gynecomastia in sex offenders undergoing treatment by temporary chemical castration.[13]

Bipolar disorder

Tamoxifen has been shown to be effective in the treatment of mania in patients with bipolar disorder by blocking protein kinase C (PKC), an enzyme that regulates neuron activity in the brain. Researchers believe PKC is over-active during the mania in bipolar patients.[14][15]

Angiogenesis and cancer

Tamoxifen is one of three drugs in an anti-angiogenetic protocol developed by Dr. Judah Folkman, a researcher at Children's Hospital at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Folkman discovered in the 1970s that angiogenesis – the growth of new blood vessels – plays a significant role in the development of cancer. Since his discovery, an entirely new field of cancer research has developed. Clinical trials on angiogenesis inhibitors have been underway since 1992 using a myriad of different drugs. The Harvard researchers developed a specific protocol for a golden retriever named Navy who was cancer-free after receiving the prescribed cocktail of celecoxib, doxycycline, and tamoxifen – the treatment subsequently became known as the Navy Protocol.[16] Furthermore tamoxifen treatment alone has been shown to have anti-angiogenetic effects in animal models of cancer which appear to be, at least in part, independent of tamoxifen's estrogen receptor antagonist properties.[17]

Control of gene expression

Finally tamoxifen is used as a research tool to trigger tissue specific gene expression in many conditional expression constructs in genetically modified animals including a version of the Cre-Lox recombination technique.[18]

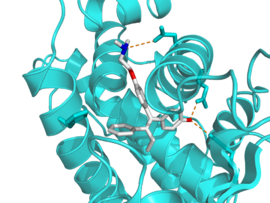

Mechanism of action

Tamoxifen competitively binds to estrogen receptors on tumors and other tissue targets, producing a nuclear complex that decreases DNA synthesis and inhibits estrogen effects. It is a nonsteroidal agent with potent antiestrogenic properties which compete with estrogen for binding sites in breast and other tissues. Tamoxifen causes cells to remain in the G0 and G1 phases of the cell cycle. Because it prevents (pre)cancerous cells from dividing but does not cause cell death, tamoxifen is cytostatic rather than cytocidal.

Tamoxifen itself is a prodrug, having relatively little affinity for its target protein, the estrogen receptor. It is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 isoform CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 into active metabolites such as 4-hydroxytamoxifen and N-desmethyl-4-hydroxytamoxifen (endoxifen)[19] which have 30-100 times more affinity with the estrogen receptor than tamoxifen itself. These active metabolites compete with estrogen in the body for binding to the estrogen receptor. In breast tissue, 4-hydroxytamoxifen acts as an estrogen receptor antagonist so that transcription of estrogen-responsive genes is inhibited.[20]

Tamoxifen binds to estrogen receptor (ER) and interacts with the DNA, it recruits proteins known as co-repressors to stop genes being switched on by estrogen. Some of these proteins include NCoR and SMRT.[21] Tamoxifen function can be regulated by a number of different variables including growth factors.[22] In fact Tamoxifen needs to block growth factor proteins such as ErbB2/HER2[23] because high levels of ErbB2 have been shown to occur in tamoxifen resistant cancers.[24]

Tamoxifen seems to require a protein PAX2 for its full anticancer effect.[25] More specifically, the ratio of PAX2 and AIB-3 predicts the efficacy of tamoxifen therapy. In the presence of high PAX2 expression, the tamoxifen/estrogen receptor complex is able to supress the expression of the pro-proliferative ERBB2 protein. In contrast, when AIB-3 expression is higher than PAX2, tamoxifen/estrogen receptor complex upregulates the expression of ERBB2 resulting in stimulation of breast cancer growth.[26][23] In about 35% of UK breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen PAX2 is, or becomes, faulty leading to resistance to the drug.[27]

Side effects

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator.[28] Even though it is an antagonist in breast tissue it acts as partial agonist on the endometrium and has been linked to endometrial cancer in some women. Therefore endometrial changes, including cancer, are among tamoxifen's side effects.[29]

The American Cancer Society lists tamoxifen as a known carcinogen, stating that it increases the risk of some types of uterine cancer while lowering the risk of breast cancer recurrence.[30] The ACS states that its use should not be avoided in cases where the risk of breast cancer recurrence without the drug is higher than the risk of developing uterine cancer with the drug.

For some women, tamoxifen can cause a rapid increase in triglyceride concentration in the blood. In addition there is an increased risk of thromboembolism especially during and immediately after major surgery or periods of immobility.[31] Tamoxifen is also a cause of fatty liver, otherwise known as steatorrhoeic hepatosis or steatosis hepatis.[32]

A significant number of tamoxifen treated breast cancer patients experience a reduction of libido.[33][34]

A beneficial side effect of tamoxifen is that it prevents bone loss by inhibiting osteoclasts by acting as an estrogen receptor agonist (i.e., mimicking the effects of estrogen) in this cell type, and therefore it prevents osteoporosis.[35][36] When tamoxifen was launched as a drug, it was thought that tamoxifen would act as an estrogen receptor antagonist in all tissue, including bone, and therefore it was feared that it would contribute to osteoporosis. It was therefore very surprising that the opposite effect was observed clinically. Hence tamoxifen's tissue selective action directly lead to the formulation of the concept of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs).[37]

Pharmacogenetics

Patients with variant forms of the gene CYP2D6 (also called simply 2D6) may not receive full benefit from tamoxifen because of too slow metabolism of the tamoxifen prodrug into its active metabolite 4-hydroxytamoxifen.[38][39] On Oct 18, 2006 the Subcommittee for Clinical Pharmacology recommended relabeling tamoxifen to include information about this gene in the package insert.[40]

Recent studies suggest that taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants such as Paxil, Prozac, etc., can decrease the effectiveness of tamoxifen, because these drugs compete for the CYP2D6 enzyme which is needed to metabolize tamoxifen into the active form endoxifen.[41]

Market

Global sales of tamoxifen in 2001 were $1,024 million.[42] Since the expiration of the patent in 2002, it is now widely available as a generic drug around the world. Barr Labs Inc had challenged the patent (which in 1992 was ruled unenforcable) but later came to an agreement with Zeneca to licence the patent and sell tamoxifen at close to Zeneca's price.[43]

Tamoxifen tablets cost about $40 to $100 per month.[7]

Discovery

In the late 1950s, pharmaceutical companies were actively researching a newly discovered class of anti-estrogen compounds in the hope of developing a morning-after contraceptive pill. Arthur L Walpole was a reproductive endocrinologist who led such a team at the Alderley Park research laboratories of ICI Pharmaceuticals. It was there in 1962 that Dora Richardson first synthesised tamoxifen, known then as ICI-46,474.[44] Walpole and his colleagues filed a UK patent covering this compound in 1962, but patent protection on this compound was repeatedly denied in the US until the 1980s.[45] Tamoxifen did eventually receive marketing approval as a fertility treatment, but the class of compounds never proved useful in human contraception. A link between estrogen and breast cancer had been known for many years, but cancer treatments were not a corporate priority at the time, and Walpole's personal interests were important in keeping support for the compound alive in the face of this and the lack of patent protection.[1]

The first clinical study took place at the Christie Hospital in 1971, and showed a convincing effect in advanced breast cancer,[46] but nevertheless ICI's development programme came close to termination when it was reviewed in 1972. It appears to have been Walpole again who convinced the company to market tamoxifen for late stage breast cancer in 1973.[45] He was also instrumental in funding V. Craig Jordan to work on tamoxifen. Approval in the US followed in 1977, but the drug was competing against other hormonal agents in a relatively small marketplace and was not at this stage either clinically or financially remarkable.

1980 saw the publication of the first trial to show that tamoxifen given in addition to chemotherapy improved survival for patients with early breast cancer.[47] In advanced disease, tamoxifen is now only recognised as effective in estrogen receptor positive (ER+) patients, but the early trials did not select ER+ patients, and by the mid 1980s the clinical trial picture was not showing a major advantage for tamoxifen.[48] Nevertheless, tamoxifen had a relatively mild side-effect profile, and a number of large trials continued. It was not until 1998 that the meta-analysis of the Oxford based Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group showed definitively that tamoxifen saved lives in early breast cancer.[49]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jordan VC (2006). "Tamoxifen (ICI46,474) as a targeted therapy to treat and prevent breast cance". Br J Pharmacol 147 (Suppl 1): S269–76. doi:. PMID 16402113.

- ↑ Jordan VC (1993). "Fourteenth Gaddum Memorial Lecture. A current view of tamoxifen for the treatment and prevention of breast cancer". Br J Pharmacol 110 (2): 507–17. PMID 8242225.

- ↑ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (03/08/2005). "Tamoxifen Information: reducing the incidence of breast cancer in women at high risk". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved on July 3, 2007.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute (2006-04-26). "Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) Trial". U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved on July 3, 2007.

- ↑ University of Pittsburgh. "STAR Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifen". Retrieved on July 3, 2007.

- ↑ Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Hoctin-Boes G, Houghton J, Locker GY, Tobias JS (2005). "Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer". Lancet 365 (9453): 60–2. doi:. PMID 15639680.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Arimidex After Two Years of Tamoxifen Reduces Recurrence in Post-Menopausal Women". BreastCancer.org. Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Jakesz R, Jonat W, Gnant M, Mittlboeck M, Greil R, Tausch C, Hilfrich J, Kwasny W, Menzel C, Samonigg H, Seifert M, Gademann G, Kaufmann M, Wolfgang J; ABCSG and the GABG (2005). "Switching of postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer to anastrozole after 2 years' adjuvant tamoxifen: combined results of ABCSG trial 8 and ARNO 95 trial". Lancet 366 (9484): 455–62. doi:. PMID 16084253.

- ↑ Steiner AZ, Terplan M, Paulson RJ (2005). "Comparison of tamoxifen and clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction: a meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. 20 (6): 1511–5. doi:. PMID 15845599.

- ↑ van Bommel EF, Hendriksz TR, Huiskes AW, Zeegers AG (2006). "Brief communication: tamoxifen therapy for nonmalignant retroperitoneal fibrosis". Ann. Intern. Med. 144 (2): 101–6. PMID 16418409.

- ↑ Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Battaglia M, Di Tonno P, Selvaggi FP, Conti G, Comeri G, Bertaccini A, Martorana G, Galassi P, Zattoni F, Macchiarella A, Siragusa A, Muscas G, Durand F, Potenzoni D, Manganelli A, Ferraris V, Montefiore F (2005). "Evaluation of tamoxifen and anastrozole in the prevention of gynecomastia and breast pain induced by bicalutamide monotherapy of prostate cancer". J Clin Oncol 23 (4): 808–15. doi:. PMID 15681525.

- ↑ Baker JS, Graham MR, Davies B (2006). "Steroid and prescription medicine abuse in the health and fitness community: A regional study". Eur. J. Intern. Med. 17 (7): 479–84. doi:. PMID 17098591.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (2007-06-13). "Q&A: Chemical castration". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved on 2007-09-10.

- ↑ "Manic Phase of Bipolar Disorder Benefits from Breast Cancer Medication". National Institutes of Mental Health (September 12, 2007). Retrieved on 2008-03-10.

- ↑ Yildiz A, Guleryuz S, Ankerst DP, Ongür D, Renshaw PF (2008). "Protein kinase C inhibition in the treatment of mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tamoxifen". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65 (3): 255–63. doi:. PMID 18316672.

- ↑ Kirk E (2002-07-24). "Dog's tale of survival opens door in cancer research". Health and Behavior. USA Today. Retrieved on 2008-06-24.

- ↑ Blackwell KL, Haroon ZA, Shan S, Saito W, Broadwater G, Greenberg CS, Dewhirst MW (November 2000). "Tamoxifen inhibits angiogenesis in estrogen receptor-negative animal models". Clin. Cancer Res. 6 (11): 4359–64. PMID 11106254. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/6/11/4359.

- ↑ Feil R, Brocard J, Mascrez B, LeMeur M, Metzger D, Chambon P (1996). "Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (20): 10887–90. doi:. PMID 8855277.

- ↑ Desta Z, Ward BA, Soukhova NV, Flockhart DA (2004). "Comprehensive evaluation of tamoxifen sequential biotransformation by the human cytochrome P450 system in vitro: prominent roles for CYP3A and CYP2D6". J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310 (3): 1062–75. doi:. PMID 15159443.

- ↑ Wang DY, Fulthorpe R, Liss SN, Edwards EA (2004). "Identification of estrogen-responsive genes by complementary deoxyribonucleic acid microarray and characterization of a novel early estrogen-induced gene: EEIG1". Mol Endocrinol 18 (2): 402–11. doi:. PMID 14605097.

- ↑ Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M (December 2000). "Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription". Cell 103 (6): 843–52. doi:. PMID 11136970.

- ↑ Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Creighton CJ, Qin L, Tsimelzon A, Huang S, Weiss H, Rimawi M, Schiff R (February 2008). "Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function". Cancer Res. 68 (3): 826–33. doi:. PMID 18245484.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hurtado1 A, Holmes KA, Geistlinger TR, Hutcheson IR, Nicholson RI, Brown M, Jiang J, Howat1 WJ, Ali S, Carroll JS (November 2008). "Regulation of ERBB2 by oestrogen receptor–PAX2 determines response to tamoxifen". Nature 456. doi:.

- ↑ Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp TA, Chamness GC, Hilsenbeck SG, Fuqua SA, Wong J, Allred DC, Clark GM, Schiff R (March 2003). "Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95 (5): 353–61. doi:. PMID 12618500.

- ↑ "New Mechanism Predicts Tamoxifen Response: PAX2 gene implicated in tamoxifen-induced inhibition of ERBB2/HER2-mediated tumor growth". www.modernmedicine.com (2008-11-13). Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ↑ "Study sheds new light on tamoxifen resistance". News. CORDIS News. Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Macrae F (2008-11-13). "Hope for millions of women as scientists unlock secret of breast cancer 'wonder' drug". Mail Online. Daily Mail (UK). Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Gallo MA, Kaufman D (1997). "Antagonistic and agonistic effects of tamoxifen: significance in human cancer". Semin Oncol 24 (Suppl 1): S1–71–S1–80. PMID 9045319.

- ↑ Grilli S (2006). "Tamoxifen (TAM): the dispute goes on". Ann Ist Super Sanita 42 (2): 170–3. PMID 17033137. http://www.iss.it/publ/anna/2006/2/422170.pdf.

- ↑ "Known and Probable Carcinogens". American Cancer Society (2006-02-03). Retrieved on 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Decensi A, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, Bettega D, Costa A, Sacchini V, Salvioni A, Travaglini R, Oliviero P, D'Aiuto G, Gulisano M, Gucciardo G, del Turco MR, Pizzichetta MA, Conforti S, Bonanni B, Boyle P, Veronesi U (2005). "Effect of tamoxifen on venous thromboembolic events in a breast cancer prevention trial". Circulation 111 (5): 650–6. doi:. PMID 15699284.

- ↑ Khalid A Osman; Meissa M Osman; Mohamed H Ahmed (2007). "Tamoxifen-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: where are we now and where are we going?". Expert opinion on drug safety 6 (1): 1–4. doi:. PMID 17181445.

- ↑ Mortimer JE, Boucher L, Baty J, Knapp DL, Ryan E, Rowland JH (1999). "Effect of tamoxifen on sexual functioning in patients with breast cancer" (abstract). J. Clin. Oncol. 17 (5): 1488–92. PMID 10334535. http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/17/5/1488.

- ↑ Cella D, Fallowfield L, Barker P, Cuzick J, Locker G, Howell A (2006). "Quality of life of post-menopausal women in the ATAC ("Arimidex", tamoxifen, alone or in combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for early breast cancer". Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 100 (3): 273–84. doi:. PMID 16944295.

- ↑ Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S, Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, Nishina H, Takeda S, Takayanagi H, Metzger D, Kanno J, Takaoka K, Martin TJ, Chambon P, Kato S (2007). "Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor alpha and induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts". Cell 130 (5): 811–23. doi:. PMID 17803905.

- ↑ Krum SA, Miranda-Carboni GA, Hauschka PV, Carroll JS, Lane TF, Freedman LP, Brown M (2008). "Estrogen protects bone by inducing Fas ligand in osteoblasts to regulate osteoclast survival". EMBO J. 27 (3): 535–45. doi:. PMID 18219273.

- ↑ Mincey BA, Moraghan TJ, Perez EA (2000). "Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in women with breast cancer". Mayo Clin Proc 75 (8): 821–9. PMID 10943237. http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.asp?ref=7508r.

- ↑ Goetz MP, Rae JM, Suman VJ, Safgren SL, Ames MM, Visscher DW, Reynolds C, Couch FJ, Lingle WL, Flockhart DA, Desta Z, Perez EA, Ingle JN (2005). "Pharmacogenetics of tamoxifen biotransformation is associated with clinical outcomes of efficacy and hot flashes". J Clin Oncol 23 (36): 9312–8. doi:. PMID 16361630.

- ↑ Beverage JN, Sissung TM, Sion AM, Danesi R, Figg WD (2007). "CYP2D6 polymorphisms and the impact on tamoxifen therapy". J Pharm Sci 96 (9): Epub ahead of print. doi:. PMID 17518364.

- ↑ Information about CYP2D6 and tamoxifen from DNADirect's website

- ↑ Jin Y, Desta Z, Stearns V, Ward B, Ho H, Lee KH, Skaar T, Storniolo AM, Li L, Araba A, Blanchard R, Nguyen A, Ullmer L, Hayden J, Lemler S, Weinshilboum RM, Rae JM, Hayes DF, Flockhart DA (2005). "CYP2D6 genotype, antidepressant use, and tamoxifen metabolism during adjuvant breast cancer treatment". J Natl Cancer Inst 97 (1): 30–9. doi:. PMID 15632378.

- ↑ "Cancer the generic impact". BioPortfolio Limited. Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ↑ "Tamoxifen". Lawsuits & Settlements. Prescription Access Litigation. Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. pp. 472 pages. ISBN 0-471-89979-8.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Jordan VC (2003). "Tamoxifen: a most unlikely pioneering medicine". Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2 (3): 205–13. doi:. PMID 12612646.

- ↑ Cole MP, Jones CT, Todd ID (1971). "A new anti-estrogenic agent in late breast cancer. An early clinical appraisal of ICI46474". Br. J. Cancer 25 (2): 270–5. PMID 5115829.

- ↑ Baum M, Brinkley DM, Dossett JA, McPherson K, Patterson JS, Rubens RD, Smiddy FG, Stoll BA, Wilson A, Lea JC, Richards D, Ellis SH (1983). "Improved survival among patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen after mastectomy for early breast cancer". Lancet 2 (8347): 450. PMID 6135926.

- ↑ Furr BJ, Jordan VC (1984). "The pharmacology and clinical uses of tamoxifen". Pharmacol. Ther. 25 (2): 127–205. doi:. PMID 6438654.

- ↑ Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (1998). "Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials". Lancet 351 (9114): 1451–67. doi:. PMID 9605801.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||