Sword

A sword is a long-edged piece of metal, used as a cutting, thrusting, and slashing weapon in many civilizations throughout the world. The word sword comes from the Old English sweord, cognate to Old High German swert, Middle Dutch swaert, Old Norse sverð (cf.Danish sværd, Norwegian sverd, Swedish svärd) Old Frisian and Old Saxon swerd and Modern Dutch zwaard and German Schwert, from a Proto-Indo-European root *swer- "to wound, to hurt".

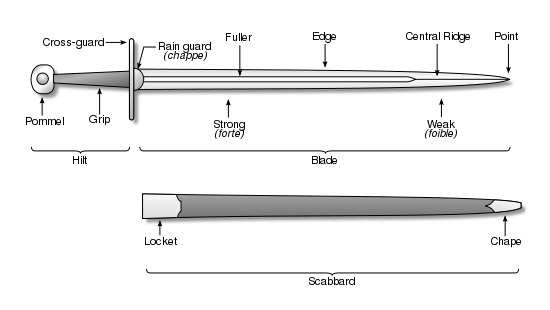

A sword fundamentally consists of a blade and a hilt, typically with one or two edges for striking and cutting, and a point for thrusting. The basic intent and physics of swordsmanship have remained fairly constant through the centuries, but the actual techniques vary among cultures and periods as a result of the differences in blade design and purpose. The names given to many swords in mythology, literature, and history reflect the high prestige of the weapon (see list of swords).

Contents |

History

Bronze Age

Humans have manufactured and used metal bladed weapons from the Bronze Age onwards. The sword developed from the dagger when the construction of longer blades became possible, from the late 3rd millennium BC in the middle-east, first in arsenic copper, then in tin-bronze. The oldest sword-like weapons are found at Arslantepe, Turkey, and date to around 3300 BC. It's however believed that these are longer daggers, and not the first ancestors of swords. Swords longer than 90 cm were rare and not practical during the Bronze Age as this length exceeds the tensile strength of bronze, which means such long swords would bend easily. It was not until the development of stronger alloys such as steel that longswords became practical for combat.

The hilt, either from organic materials or bronze (the latter often highly decorated with spiral patterns, for example), at first simply allowed a firm grip and prevented the hand from slipping onto the blade when executing a thrust or the blade flying out of the hand in a cut. Some of the early swords typically had long and slender shaped blades intended for thrusting. Later swords were broader and were both cutting and thrusting weapons. A typical variant for European swords is the leaf-shaped blade, which was most common in North-West Europe at the end of the Bronze Age, in the UK and Ireland in particular. The Naue Type II Swords which spread from Southern Europe into the Mediterranean, have been linked by Robert Drews with the Late Bronze Age collapse.[1]

Sword production in China is attested from the Bronze Age Shang Dynasty. The technology for bronze swords reached its high point during the Warring States period and Qin Dynasty. Amongst the Warring States period swords, some unique technologies were used, such as casting high tin edges over softer, lower tin cores, or the application of diamond shaped patterns on the blade (see sword of Goujian). Also unique for Chinese bronzes is the consistent use of high tin bronze (17-21% tin) which is very hard and breaks if stressed too far, whereas other cultures preferred lower tin bronze (usually 10%), which bends if stressed too far. Although iron swords were made alongside bronze, it wasn't until the early Han period that iron completely replaced bronze.

The earliest available Bronze age swords of copper discovered from the Harappan sites date back to 2300 BC. Swords have been recovered in archaeological findings throughout the Ganges-Jamuna Doab region of India, consisting of bronze but more commonly copper.[2] Diverse specimens have been discovered in Fatehgarh, where there are several varieties of hilt.[2] These swords have been variously dated to periods between 1700-1400 BCE, but were probably used more extensively during the opening centuries of the 1st millennium BCE.[2]

Not every culture that used bronze also developed swords. For example, the steppe tribes preferred short daggers (the akinakes). In South America, bronze was used by the Incas, and although the concept of the sword was known in the form of wooden swords with stone edges (the macahuitl), they did not develop bronze swords.

Iron Age

Iron swords became increasingly common from the 13th century BC. The Hittites, the Mycenaean Greeks, and the Proto-Celtic Hallstatt culture (8th century BC) figured among the early users of iron swords. Iron has the advantage of mass-production due to the wider availability of the raw material. Early iron swords were not comparable to later steel blades. The iron was not quench-hardened although often containing sufficient carbon, but work-hardened like bronze by hammering. This made them comparable or only slightly better in terms of strength and hardness to bronze swords. They could still bend during use rather than spring back into shape. But the easier production, and the better availability of the raw material for the first time permitted the equipment of entire armies with metal weapons, though Bronze Age Egyptian armies were at times fully equipped with bronze weapons.

By the time of Classical Antiquity and the Parthian and Sassanid Empires in Iran, iron swords were common. The Greek xiphos and the Roman gladius are typical examples of the type, measuring some 60 to 70 cm. The late Roman Empire introduced the longer spatha (the term for its wielder, spatharius, became a court rank in Constantinople), and from this time, the term longsword is applied to swords comparatively long for their respective periods.

Chinese steel swords made their appearance from the 3rd century BCE Qin Dynasty. The Chinese Dao (刀 pinyin dāo) is single-edged, sometimes translated as sabre or broadsword, and the Jian (劍 pinyin jiàn) double-edged.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions swords of Indian iron and steel being exported from India to Greece.[3] Indian Blades made of Damascus steel also found their way into Persia.[4]

Middle Ages

The spatha type remained popular throughout the Migration period and well into the Middle Ages. Vendel Age spathas were decorated with Germanic artwork (not unlike the Germanic bracteates fashioned after Roman coins). The Viking Age saw again a more standardized production, but the basic design remained indebted to the spatha.

Around the 10th century, the use of properly quench hardened and tempered steel started to become much more common than in previous periods. The Frankish Ulfberht blades (the name of the maker inlaid in the blade) were of particularly consistent high quality. Charles the Bald tried to prohibit the export of these swords, as they were used by Vikings in raids against the Franks.

It is only from the 11th century that Norman swords begin to develop the quillons or crossguard. During the Crusades of the 12th to 13th century, this cruciform type of arming sword remained essentially stable, with variations mainly concerning the shape of the pommel. These swords were designed as cutting weapons, although effective points were becoming common to counter improvements in armour.

As steel technology improved, single-edged weapons became popular throughout Asia. Derived from the Chinese Jian or dao, the Korean hwandudaedo are known from the early medieval Three Kingdoms. Production of the Japanese tachi, a precursor to the katana, is recorded from ca. 900 CE (see Japanese sword).

The swords manufactured in Indian workshops find mention in the writing of Muhammad al-Idrisi.[5]

Wootz steel which is also known as Damascus steel was a unique and highly prized steel developed on the Indian subcontinent as early as the 5th century BCE. Its properties were unique due to the special smelting and reworking of the steel creating networks of iron carbides described as a globular cementite in a matrix of pearlite. This gave the blade a very hard cutting edge and beautiful patterns. For obvious reasons it became a very popular trading material. The use of Damascus steel in swords became extremely popular in the 16th and 17th centuries.[6] [7]

Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

From around 1300 to 1500, in concert with improved armour, innovative sword designs evolved more and more rapidly. The main transition was the lengthening of the grip, allowing two-handed use, and a longer blade. By 1400, this type of sword, at the time called langes Schwert (longsword) or spadone, was common, and a number of 15th and 16th century Fechtbücher offering instructions on their use survive. Another variant was the specialized armour-piercing swords of the estoc type. The longsword became popular due to its extreme reach and cutting and thrusting abilities. The estoc became popular because of its ability to thrust into the gaps between plates of armor. The grip was sometimes wrapped in wire or coarse animal hide to provide a better grip and to make it harder to knock a sword out of the user's hand.

In the 16th century, the large Doppelhänder (called the Zweihänder today; both German names refer to the use of both hands) concluded the trend of ever-increasing sword sizes (mostly due to the beginning of the decline of plate armor and the advent of firearms), and the early Modern Age saw the return to lighter, one-handed weapons.

The Japanese katana reached the height of its development at about this time. In the 15th and 16th centuries, samurai increasingly found a need for a sword to use in closer quarters, leading to the creation of the modern katana.

The sword in this time period was the most personal weapon, the most prestigious, and the most versatile for close combat, but it came to decline in military use as technology changed warfare. However, it maintained a key role in civilian self-defense.

Modern age

Some think the rapier evolved from the Spanish espada ropera in the 16th century. The rapier differed from most earlier swords in that it was not a military weapon but a primarily civilian sword. Both the rapier and the Italian schiavona developed the crossguard into a basket-shaped guard for hand protection. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the shorter smallsword became an essential fashion accessory in European countries and the New World, and most wealthy men and military officers carried one. Both the smallsword and the rapier remained popular dueling swords well into the 18th century.

As the wearing of swords fell out of fashion, canes took their place in a gentleman's wardrobe. Some examples of canes—those known as sword canes or swordsticks—incorporate a concealed blade. The French martial art la canne developed to fight with canes and swordsticks and has now evolved into a sport.

Towards the end of its useful life, the sword served more as a weapon of self-defense than for use on the battlefield, and the military importance of swords steadily decreased during the Modern Age. Even as a personal sidearm, the sword began to lose its preeminence in the early 19th century, paralleling the development of reliable handguns.

Swords continued in use, but were increasingly limited to military commissioned officers' and non-commissioned officers' ceremonial uniforms, although most armies retained heavy cavalry until well after World War I. For example, the British Army formally adopted a completely new design of cavalry sword in 1908, almost the last change in British Army weapons before the outbreak of the war. The last units of British heavy cavalry switched to using armoured vehicles as late as 1938. Swords and other dedicated melee weapons were used occasionally by various countries during World War II, but typically as a secondary weapon as they were outclassed by contemporaneous firearms.

The production of replicas of historical swords originates with 19th century historicism. Contemporary replicas can range from cheap factory produced look-alikes to exact recreations of individual artifacts, including an approximation of the historical production methods.

Terminology

The sword consists of the blade and the hilt. The term scabbard applies to the cover for the sword blade when not in use.

Blade

Three types of attacks can be performed with the blade: striking, cutting, and thrusting. The blade can be double-edged or single-edged, the latter often having a secondary "false edge" near the tip. When handling the sword, the long or true edge is the one used for straight cuts or strikes, while the short or false edge is the one used for backhand strikes. Some hilt designs define which edge is the 'long' one, while more symmetrical designs allow the long and short edges to be inverted by turning the sword of one's hand on the hilt.

The blade may have grooves known as fullers for lightening the blade while allowing it to retain its strength and stiffness, similar to the effect produced by a steel I-beam used in construction. The blade may taper more or less sharply towards a point, used for thrusting. The part of the blade between the Center of Percussion (CoP) and the point is called the foible (weak) of the blade, and that between the Center of Balance (CoB) and the hilt is the forte (strong). The section in between the CoP and the CoB is the middle. The ricasso or shoulder identifies a short section of blade immediately forward of the guard that is left completely unsharpened, and can be gripped with a finger to increase tip control. Many swords have no ricasso. On some large weapons, such as the German Zweihänder, a metal cover surrounded the ricasso, and a swordsman might grip it in one hand to wield the weapon more easily in close-quarter combat. The ricasso normally bears the maker's mark. On Japanese blades this mark appears on the tang (part of the blade that extends into the hilt) under the grip.

- In the case of a rat-tail tang, the maker welds a thin rod to the end of the blade at the crossguard; this rod goes through the grip (in 20th century and later construction). This occurs most commonly in decorative replicas, or cheap sword-like objects. Traditional sword-making does not use this construction method, which does not serve for traditional sword usage as the sword can easily break at the welding point.

- In traditional construction, the swordsmith forged the tang as a part of the sword rather than welding it on. Traditional tangs go through the grip: this gives much more durability than a rat-tail tang. Swordsmiths peened such tangs over the end of the pommel, or occasionally welded the hilt furniture to the tang and threaded the end for screwing on a pommel. This style is often referred to as a "narrow" or "hidden" tang. Modern, less traditional, replicas often feature a threaded pommel or a pommel nut which holds the hilt together and allows dismantling.

- In a "full" tang (most commonly used in knives and machetes), the tang has about the same width as the blade, and is generally the same shape as the grip. In European or Asian swords sold today, many advertised "full" tangs may actually involve a forged rat-tail tang.

At the base of the blade, a flap of leather could be attached to a sword's crossguard, the Chappe which serves to protect the mouth of the scabbard and prevent water from entering. It is also called a Rain Guard.

From the 18th century onwards, swords intended for slashing, i.e., with blades ground to a sharpened edge, have been curved with the radius of curvature equal to the distance from the swordman's body at which it was to be used. This allowed the blade to have a sawing effect rather than simply delivering a heavy cut. European swords, intended for use at arm's length, had a radius of curvature of around a meter. Middle Eastern swords, intended for use with the arm bent, had a smaller radius.

Hilt

The hilt is the collective term of the parts allowing the handling and control of the blade, consisting of the grip, the pommel, and a simple or elaborate guard, which in post-Viking Age swords could consist of only a crossguard (called cruciform hilt). The pommel, in addition to improving the sword's balance and grip, can also be used as a blunt instrument at close range. It may also have a tassel or sword knot.

The tang consists of the extension of the blade structure through the hilt.

Scabbard

The scabbard is a protective cover often provided for the sword blade. Over the millennia, scabbards have been made of many materials, including leather, wood, and metals such as brass or steel. The metal fitting where the blade enters the leather or metal scabbard is called the throat, which is often part of a larger scabbard mount, or locket, that bears a carrying ring or stud to facilitate wearing the sword. The blade's point in leather scabbards is usually protected by a metal tip, or chape, which on both leather and metal scabbards is often given further protection from wear by an extension called a drag, or shoe.

Typology

Swords can fall into categories of varying scope. The main distinguishing characteristics include blade shape (cross-section, taper, and length), shape and size of hilt and pommel, age, and place of origin.

For any other type than listed below, and even for uses other than as a weapon, see the article Sword-like object.

Single-edged and double-edged swords

As noted above, the terms longsword, broad sword, great sword, and Gaelic claymore are used relative to the era under consideration, and each term designates a particular type of sword.

One strict definition of a sword restricts it to a straight, double-edged bladed weapon designed for both slashing and thrusting. However, general usage of the term remains inconsistent and it has important cultural overtones, so that commentators almost universally recognize the single-edged swords such as Asian weapons (dāo 刀, katana 刀) as "swords", simply because they have a prestige akin to their European counterparts.

In most of Asian countries, sword (jian 劍, ken, pedang) is double-edged straight bladed weapon, while knife or saber (dāo 刀, do, pisau, golok) refer to single-edged one. Thus, a katana should not be translated to samurai sword.

Europeans also frequently refer to their own single-edged weapons as swords — generically backswords, including sabres. Other terms include falchion, scimitar, cutlass, dussack, Messer or mortuary sword. Many of these refer to essentially identical weapons, and the different names may relate to their use in different countries at different times. A machete as a tool resembles such a single-edged sword and serves to cut through thick vegetation, and indeed many of the terms listed above describe weapons that originated as farmers' tools used on the battlefield.

Single-handed

- Bronze Age swords, length ca. 60 cm, leaf shaped blade.

- Iron Age swords like the xiphos, gladius and jian 劍, similar in shape to their Bronze Age predecessors.

- Spatha, measuring ca. 80–90 cm. similar to the Viking sword

- The classical arming sword of Medieval Europe, measuring up to ca. 110 cm.

- The late medieval Swiss baselard and the Renaissance Italian cinquedea and German Katzbalger essentially re-introduce the functionality of the spatha, coinciding with the strong cultural movement to emulate the Classical world.

- The cut & thrust swords of the Renaissance, similar to the older arming sword but balanced for increased thrusting.

- The Turkish blade; yatagan ( Yatağan in Turkish) used from 16th Century to 19th century.

- Light dueling swords, like the rapier and the smallsword, in use from Early Modern times.

- The Japanese short sword, or wakizashi

- The ida of the Yoruba tribe of West Africa. It can also be regarded as a two-handed sword.

- The Indian tulwar

- The Arabian scimitar, the similar Persian shamshir.

- The East Indian kris, with a wavy double-edged blade.

- The Fillipino itak, (image) used by pre-Spanish Filipinos or Austronesians as a primary weapon in protecting its boundaries.

- The Korean Hwandudaedo (Hwando), or a sword with a short handle and a ring-shaped pommel and a wire grip.

- The Aztec Macana, a wooden sword using obsidian shards in the blade.

Two-handed

- The Japanese samurai sword, the katana, tachi or nodachi

- The Indian khanda

- The longsword (and bastard sword/hand-and-a-half sword) of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

- The 16th century Doppelhänder or Zweihänder (German for "double-hander" or "two-hander").

- The Chinese anti-cavalry sword, zhanmadao of the Song Dynasty.

- The Scottish Highland claymore, (or claidheamh mór-gàidhlig, great sword); in use until the 18th century.

Punishment devices

- Real swords can be used to administer various physical punishments: to perform either capital punishment by decapitation (the use of the sword, an honorable weapon on military men, was regarded as privilege) or non-surgical amputation. In Scandinavia, where beheading has been the traditional means of capital punishment, noblemen were beheaded with a sword and commoners with an axe.

- Similarly paddle-like sword-like devices for physical punishment are used in Asia, in western terms for paddling or caning, depending whether the implement is flat or round.

- The shinai, a practice sword, is also used in Japan as a spanking implement, particularly in esteemed private extracurricular schools.[8]

Famous swords

Apart from the aforementioned types of symbolic swords, the following individually named swords are noteworthy:

Swords in History

- See also: Types of swords#History and mythology

- Sword of Goujian, a historical artifact from the Spring and Autumn Period.

- Zulfiqar - Sword of the Muslim Prophet Muhammad, Ali ibn Abu Talib and later Husayn ibn Ali in the Battle of Karbala.

- Honjo Masamune, Sword of the Tokugawa shogunate, a feudal military dictatorship of Japan established in 1603.

- Jewelled Sword of Offering, Sword of King George IV of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1820-1830).

- Seven-Branched Sword, which Wa received from Baekje.

- Sword of Boabdil, Sword of the last Moorish King in Spain.

- Tizona, El Cid's personal sword which exists to this day in Spain as a national treasure.

- Colada, the other sword of El Cid.

- Lobera, the sword of the king Saint Ferdinand III of Castile

- The Wallace Sword, a large Scottish Claymore believed to have been used by famous Scottish Patriot and knight William Wallace, when leading the resistance against England in the late 13th century.

- A Mameluke sword was given by Prince Hamet Karamali to Presley O'Bannon, an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps, during his participation in the First Barbary War.

- Sword of Tippu Sultan

Tippu Sultan had lost his sword in a war with the Nairs of Travancore in which, he was defeated. The Nairs under the leadership of Raja Kesavadas, defeated the Mysore army near Aluva. The Maharaja, Dharma Raja, gifted the famous sword to the Nawab of Arcot, from where the sword went to London. The sword was on display at the Wallace Collection, No. 1 Manchester Square, London. At an auction in London in 2004, the industrialist-politician Vijay Mallya purchased the sword of Tippu Sultan and some other historical artifacts, and brought them back to India for public display after nearly two centuries.

Swords of myth and legend

- See also: Types of swords#History and mythology

- Arondight - Sword of Lancelot

- Attila the Hun's sword, which he claimed was the sword of Mars, the Roman god of war

- Caladbolg - Sword of Fergus mac Róich

- Claíomh Solais - Sword of Nuada Airgeadlámh, legendary king of Ireland

- Colada, the other sword of El Cid.

- Crocea Mors - Sword of Julius Caesar

- Curtana - Sword of Ogier the Dane , a legendary Danish hero, and a paladin of Charlemagne

- Durendal - Sword of Roland, one of Charlemagne's paladins

- Excalibur/Caliburn/Caledflwch - Sword of King Arthur

- Flaming sword - Sword referred to in the Bible. This is a sword that has flames coming off of the blade.

- Fragarach - Sword of Manannan mac Lir and Lugh Lamfada

- Gram (Balmung) (Nothung) - Sword of Siegfried, hero of the Nibelungenlied

- Hauteclere - Sword of Olivier, a French hero depicted in the Song of Roland

- Heaven's Will/The Will of Heaven/Thuan Thien/Thuận Thiên. Sword of Vietnamese King Le Loi

- Hrunting - Sword lent to Beowulf by Unferth, ineffective against Grendel's mother

- Joyeuse - Sword of Charlemagne

- Kusanagi - Sword of Susanoo

- Lobera, the sword of the king Saint Ferdinand III of Castile

- Naegling - Sword of Beowulf in his old age, used to fight the dragon

- Shamshir-e Zomorrodnegar - Sword of King Solomon(in Persian folklore)

- Taming Sari - The Kris belonging to the Malay warrior Hang Tuah of the Malacca Sultanate.

- Tizona, El Cid's personal sword which exists to this day in Spain as a national treasure.

- Tyrfing - Cursed sword that causes eventual death to its wielder and their kin

Swords of modern fiction

- See also: Category:Fictional swords

- The Lightsaber is a sword concept featured in the Star Wars universe. Its popularity has inspired similar laser based swords to have been used in other works of science fiction media.

- Various swords from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, including Narsil (later Andúril), Sting, Orcrist (sword of Thorin), Guthwine (sword of Éomer), Herugrim (sword of King Théoden) and Glamdring, sword of Gandalf.

- Rhindon is the gold-hilted blade of the High King Peter Pevensie in C.S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia.

- Grayswandir is the silver blade of prince Corwin of Amber in Roger Zelazny's fiction book series "Amber Chronicles". Its sister blade, Werewindle, belongs to Corwin's brother Brand.

- The Zanbato is an incredibly large type of Japanese sword with a mysterious historical background that has inspired various fictional swords found in a wide variety of today's media including anime television, books and video games. Most unrealistically large swords such as the Buster Sword or the Tetsusaiga found in Japanese media today are inspired by the zanbatō.

- The Vorpal blade is a sword from the poem Jabberwocky. It has since been adopted into modern media as a type of magic sword. Similar magical swords have become common in fantasy literature, games, and art, but this particular sword has had its name continuously mentioned and spread among many works.

- Frostmourne is the soul stealing blade of Arthas in the Warcraft series.

- The Sword of Kahless - Sword of the legendary Klingon warrior Kahless

- The Soul Reaver, wielded by the protagonists Kain and Raziel in the Legacy of Kain video game series by Eidos Interactive and Crystal Dynamics.

- Drizzt Do'Urden, a fictional drow and the main protagonist in R.A. Salvatore's book series, wields a pair of magically enchanted curved swords, Scimitars, named Twinkle and Icingdeath. Twinkle, Drizzt's preferred blade, glows a bright blue when enemies are near, Drizzt has displayed the ability to control this glow and has been able to will the blade to go dark or to give off large amounts of light. Icingdeath can counter the effects of any type of fire, both natural and magical. The wielder can withstand the breath of a dragon or walk into a massive furnace without suffering the slightest of burns.

- Zar'Roc, Morzan's legendary sword in the Inheritance Cycle, meaning "misery". The sword is taken from Morzan by Brom, then passed down to Eragon, who loses it to Murtagh.

- Brisingr, meaning fire, Eragon's sword from the Inheritance Cycle, forged by Rhunon through Eragon's hands in the third volume, "Brisingr". Every time Eragon says his Sword's name it bursts in to flame, hence its name.

- The Master Sword, the legendary Evil's Bane, used by Link in The Legend of Zelda series

- Zangetsu, or "Moon Cutter", is the Zanpakuto used by Ichigo Kurosaki, the main protagonist of the Bleach anime series

See also

- Types of swords

- Swordsmanship

- Historical European Martial Arts

- German school of swordsmanship

- Italian school of swordsmanship

- Chinese martial arts

- Eskrima (Filipino Martial Arts)

- Fencing

- Krabi Krabong (Thailand Martial Arts)

- Banshay (Burmese Martial Arts)

- Silat (Malay Martial Arts)

- Kenjutsu

- Historical European Martial Arts

- sword-like objects

- macuahuitl

- Knight

- Oakeshott typology

- Waster

- Sword making

- List of sword manufacturers

- Sword of Damocles

Notes

- ↑ The Naue Type II Sword

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Allchin, pages 111-114

- ↑ Prasad, chapter IX

- ↑ Prasad, chapter IX

- ↑ Edgerton, page 56

- ↑ Maryon, Herbert, "Pattern-welding and Damascening of Sword-blades: Part I - Pattern-Welding," Studies in Conservation 5 (1960), p. 25 - 37. A brief review article by the originator of the term "pattern-welding" accurately details all the salient points of the construction of pattern-welded blades and of how all the patterns observed result as a function of the depth of grinding into a twisted rod structure. The article also includes a brief description of pattern-welding as encountered in the Malay keris.

- ↑ Maryon, Herbert, "Pattern-welding and Damascening of Sword-blades: Part 2: The Damascene Process," Studies in Conservation 5 (1960), p. 52 - 60. A detailed discussion of Eastern wootz Damascene steels.

- ↑ [1]

References

- Allchin, F.R. in South Asian Archaeology 1975: Papers from the Third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, Held in Paris (December 1979) edited by J.E.van Lohuizen-de Leeuw. Brill Academic Publishers, Incorporated. 106-118. ISBN 9004059962.

- Prasad, Prakash Chandra (2003). Foreign Trade and Commerce in Ancient India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 8170170532.

- Edgerton; et al. (2002). Indian and Oriental Arms and Armour. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486422291.

- Withers, Harvey J S; World Swords 1400 - 1945, Studio Jupiter Military Publishing (2006). ISBN 095491011.

Further reading

- Kao Ch'ü-hsün (1959/60). "THE CHING LU SHRINES OF HAN SWORD WORSHIP IN HSIUNG NU RELIGION." Central Asiatic Journal 5, 1959-60, pp. 221-232.

External links

- Featured articles relating to the sword at myArmoury.com

- An Introduction to the Sword (myArmoury.com article)

- How Were Swords Really Made? by John Clements (ARMA)

- How Stuff Works: How Sword Making Works

- Swords around the World

- The Oakeshott Institute

- Japanese Sword Arts FAQ

- Technique of Katana Sword Drawing - IAI-DO

- The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts

- Medieval Sword Resource Site (vikingsword.com)

- Sword Articles

- myArmoury.com

- SwordWiki.org

- Wikibooks:Sword construction